Books: Teddy Roosevelt: Top Cop, Jonah Lehrer and Other Must-Read Books

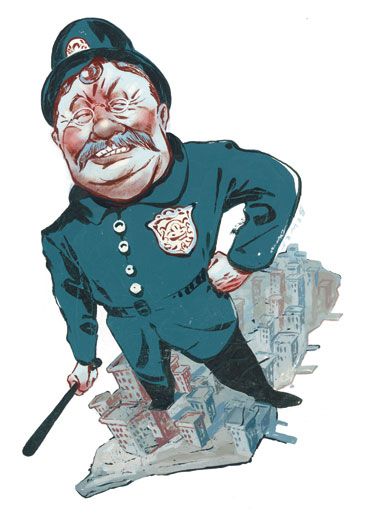

TR’s rough ride as New York’s police chief shaped the man who became president just six years later

Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Doomed Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York

Richard Zacks

When he left a comfortable job in the U.S. Civil Service in 1895 to become the chief commissioner of New York’s police department, 35-year-old Theodore Roosevelt was ill prepared for the bureaucratic tangles and urban pathologies that faced him. The city was a violent, crooked, crime-ridden place. One notorious police captain collected illicit $500 “initiation” fees from the 50 brothels in his ward—a tidy $25,000 bonus. Thirty thousand prostitutes roamed the streets. Twenty thousand people—on any given night—had no home.

TR was formidable in his attack on crooked cops. “When he asks a question, Mr. Roosevelt shoots it at the poor trembling policeman as he would shoot a bullet at a coyote,” the New York World reported. But the character traits that would make him a beloved president—stubbornness, confidence, daring—did not always serve him well in the city. Laws against Sunday saloons had been on the books since 1857, but it was TR who insisted on enforcing them, going so far as to ban drinking after midnight Saturday. This was not a popular move. Vice, Zacks writes, flourished. “Suppressed in one place, it emerged elsewhere.” And Roosevelt could be the ultimate micromanager, even insisting that the department enforce existing ordinances against discarded banana peels. “War on the Banana Skin,” the New York Times announced.

Just a year and a half in, Roosevelt was eager to get out. “I do not object to any amount of work,” he wrote to his friend Henry Cabot Lodge, “but here at the last, I was playing against stacked cards.” True enough, the police board’s other three commissioners often thwarted the Republican chief, especially the wily Democrat Andrew Parker, who relished blocking TR’s efforts to promote favorite officers. Roosevelt pulled strings to go to Washington as assistant secretary of the Navy in the McKinley administration. “It is hard to see how the Administration could have made a selection better calculated to please New Yorkers,” the World quipped.

Other biographers have glossed over Roosevelt’s two-year police stint, but Zacks shows it was a crucial period in the evolution of the 26th president. Great men, this book proves, are built not only from innate virtues and epic battles but also from wisdom earned in quotidian disagreements. The job “did as much for Roosevelt as Roosevelt did for the job,” Zacks writes.“He learned the impracticality of bitter feuds, the dangers of impulsive crusades.” The work propelled TR to national prominence, toughened his skin and, perhaps most important, established him as a reformer. To TR, Zacks writes, reform became the “bedrock for purifying politics and saving democracy.”

Imagine: How Creativity Works

Jonah Lehrer

There are the artists and the inventors—and then there are the rest of us, dutifully laboring away without the benefit of genius or the lightning bolt of inspiration. Or so it seems. But creativity, Jonah Lehrer claims in this breezy digest of recent research, isn’t the mysterious gift of a standoffish muse. It can be studied, he says, and “we can make it work for us.” That doesn’t mean the lessons are straightforward. Sometimes caffeine will spur innovation; other times a relaxing shower will do the trick. Cities are often idea incubators, except when quietude is required. Ceaseless exertion is necessary, although there is value in getting stuck. Lehrer, a journalist whose earlier Proust Was a Neuroscientist covered similar ground, has gathered nuggets that feel revelatory and at times even practical. Attention-deficit disorders can be a creative boon, forcing “the brain to consider a much wider range of possible answers,” he writes. Limited experience can have advantages; “the young know less, which is why they often invent more.”

Alcatraz: History and Design of a Landmark

Donald MacDonald and Ira Nadel

With lively illustrations by the San Francisco architect Donald MacDonald and text by MacDonald and Ira Nadel, a Vancouver-based writer, this is an easygoing look at one of the nation’s most eerily endearing attractions. It conveys a sense of the sometimes organic, sometimes engineered evolution of Alcatraz—from its earliest incarnation as a fortress to the first U.S. maximum security prison in 1934 to the tourist attraction (and dramatic movie and TV setting) it is today. The Rock is the only federal prison ever opened to the public, with a million visitors a year. It housed its share of famous criminals—Al Capone, “Machine Gun” Kelly. Robert “Birdman” Stroud, subject of the 1962 movie starring Burt Lancaster, did not in fact keep birds at Alcatraz but, rather, at Leavenworth; he’s said to be the author of “the first pet disease book published in America,” 1933’s Diseases of Canaries. The island was also home to staff during its federal prison period, including 60 families and almost 70 children. Some of the inmates, MacDonald and Nadel say, baby-sat or cut the kids’ hair, while the kids occasionally watched movies in the prison theater after the criminals had their viewing. Before any people arrived, Alcatraz was likely home to a major seabird colony—and many birds persisted. “There was a lot to despise about the place,” said one prisoner, “but I really hated those birds.” The book is not exhaustive—at times its treatment of history is glancing. A 19-month American Indian occupation of the island in the late 1960s, for example, gets not much more attention than the wildlife and foliage currently there (even though MacDonald’s back-flap bio teases with the tidbit that he participated in the siege!). Clearly, though, the aim is to provide a rich picture book for grown-ups. And that it does handsomely.

Horseshoe Crabs and Velvet Worms: The Story of the Animals and Plants That Time Has Left Behind

Richard Fortey

This charming book from the former senior paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London follows the author’s travels as he hunts for specimens that illustrate evolution. Along with the titular creatures, Fortey seeks stromatolites in Australia (sedimentary accretions that are analogues of “the most ancient organic structures on earth”) and ginkgo trees in China (“another survivor from deep geological time”) as well as numerous others. These durable species, surviving millions of years while others come and go, offer “a kind of telescope to see back in time,” Fortey writes. The view afforded will probably be most intriguing to those already possessing an appetite for natural science, but novices will delight in Fortey’s personable and apt descriptions. The chitinous peaks of a horseshoe crab’s shell are “rather like the perky eyebrows I associate with clerics of a certain age”; seaweed “swirls like a saucy Spanish skirt.” Arguing for the combined benefit of genomic, anatomical and fossil-based analysis, Fortey proclaims: “Let us carry on digging!” I say: Let him keep writing!

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/books-chloe-schama-240.jpg)