With the Borden Murder House in New Hands, Will Real History Get the Hatchet?

For the amateur detectives who are still trying to solve the case, the recent developments are causing consternation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/d2/5ad2ce55-91e8-4ef5-9b80-c14d2437fa42/gettyimages-630369154.jpg)

Two people were murdered in 1892, and the nation can’t stop thinking about them.

Andrew and Abby Borden were in their Fall River, Massachusetts, home when someone took a hatchet to their heads with repeated blows. That someone, the reason behind their deaths’ permanence in historical memory, was likely their daughter/step-daughter Lizzie. The saga of Lizzie Borden, from her odd demeanor upon “finding” her father’s body—one police officer told the court she was “cool” with a steady voice and no tears — to her repeated contradictions around her alibi, to her reputation as just a sedate church volunteer and not a frenzied killer, has captured the nation’s attention for generations. Yet some recent changes to the site of the killings may forever affect how the narrative gets told.

What happened to Andrew and Abby Borden that day is arguably the most famous true crime case after the 1888 Jack the Ripper horrors. In just the past three years alone, books, a feature film, and television treatments have chronicled the Borden murders. A 2009 rock opera titled LIZZIE has been performed in over 60 cities in six countries since its debut and has ten upcoming productions as of this writing (one amazing number has Lizzie’s sister, Emma, singing in staccato, “What the f---, Lizzie, what the f---!?”).

It’s hard to encapsulate the complexities of August 4, 1892, but here’s (ahem) a stab. That morning, the family’s maid, Bridget Sullivan, awoke from a nap to Lizzie calling to her, “Come down quick! Father’s dead; somebody came in and killed him!” Sullivan confirmed that Andrew had been struck 10 or 11 times while reclining on the sitting room sofa, his face a sea of blood. Lizzie sent her out of the house to fetch various people, remaining inside. (Emma was out of town and a visiting relative had already left for the day).

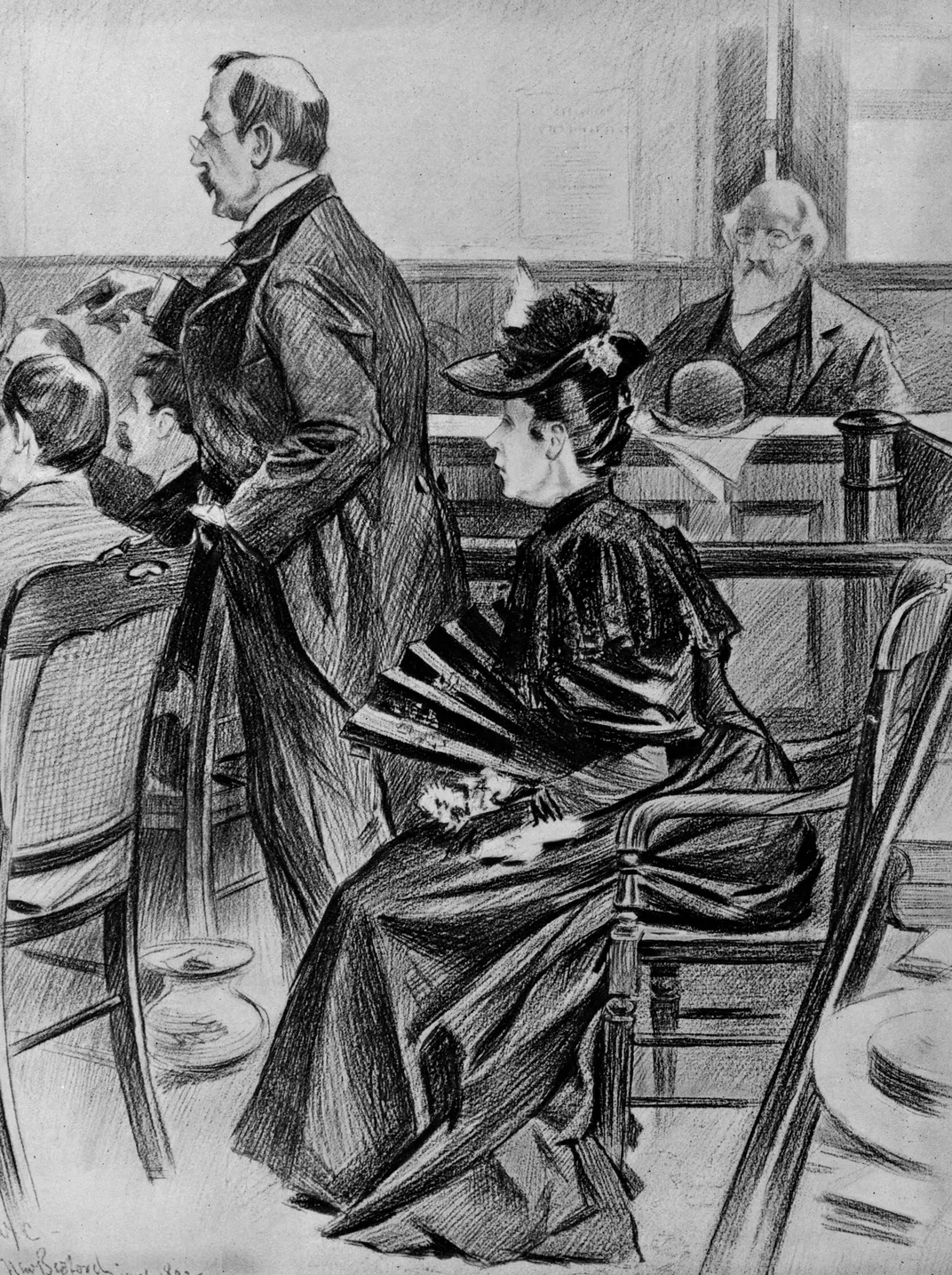

As locals began to gather at the scene, the question was raised of Abby Borden’s whereabouts. Lizzie said Abby, her stepmother, had gone out to tend to a sick friend (no such friend ever later emerged), then said she thought she had heard Abby come into the house. Sullivan and a neighbor discovered her body upstairs in the guest room with 19 hatchet wounds. Forensics determined that she had predeceased her husband by at least an hour, and attention slowly began to focus on Lizzie, who stood to financially benefit if her stepmother’s relatives were passed over. Lizzie was arrested for the murders on August 11, and a year later, after being tried by a jury of men who remained sequestered for a full hour to make it seem like they truly discussed the case, Lizzie was acquitted.

Her attorney repeatedly called Lizzie a “young woman” (she was 32). He argued, “There was nothing whatever between this father and this daughter that should cause her to do such a wicked, wicked act.” It probably helped that she fainted in court. Yet while she was found not guilty, the court of popular opinion indicted her based on the evidence before them: her attempts to buy poison the day before the murders (everyone in the household but her was vomiting the day before), telling a friend she thought “something bad might happen,” and the amount of time that passed between the two murders in a locked house. This meant that the killer somehow lay in wait for at least an hour, avoiding being detected by Lizzie, Bridget, and, after he came home from errands, Andrew.

After the acquittal, Lizzie moved to the fancy side of town and bought a large mansion for herself and Emma (Emma abruptly left in 1905, and the sisters became estranged). Lizzie enjoyed entertaining theater folk at the house she named Maplecroft, although neighbor children tormented her with “ding dong dash” and carriages would come from the train station to pause in front of the house, with a tour guide loudly proclaiming the crimes she had been accused of. In later years, her life got quieter until she died in 1927 at the age of 66.

Both the murder house and the house Lizzie bought after her acquittal recently went on the housing market. The latter residence, lavish and furnished, remains unsold, but the more modest murder house, which has operated as a themed bed-and-breakfast since 2004, sold to entrepreneur Lance Zaal in May for close to $2 million. The owner of Ghost Adventures, Zaal plans to paranormalize the site with a bigger emphasis on capturing the ghostly echoes from its former inhabitants. Along with the daily preexisting 90-minute house tour, he has added a 90-minute ghost tour and a two-hour ghost hunt. He’s planning to launch a podcast, virtual experiences, themed dinners, bedtime ghost tours of Fall River, and murder mystery nights. “We want to get the Lizzie Borden story into the hands of more people,” he says. He sees the house as a wedding venue and plans to refit the cellar to create a rentable bedroom to join the existing six. He especially wants guests to video themselves reacting to paranormal phenomena in the house.

The parking lot will host special events, including axe-throwing. This detail strikes a nerve for anyone who cringes about playfulness around the Borden deaths, but Zaal responds, “Who’s being murdered here? I mean, no one’s murdering anybody....We want you to have a good time.”

One change in particular represents the decisions Zaal faces as the new proprietor of a historically relevant, habitable house. He plans to replace the kitchen stove, an iron behemoth, with a modern one. Although the antique is not original, it allowed visitors to visualize Lizzie burning her dress inside it once she learned she was a suspect (true fact). Yet when Zaal tells of the faulty pilot light, it’s clear the stove has to go. “Evacuating people in the middle of the night in winter with gas filling up the house and fire trucks coming, we don’t want to risk burning the house down,” he says. “We have to cook. We have to keep people’s lives safe.”

His ideas have some Lizzie devotees concerned.

“I’m not into paranormal at all,” says Shelley Dziedzic, an armchair sleuth with a blog called Lizzie Borden Warps and Wefts. She’s been thinking about the case since 1991. “I’m a history freak.” Her main interest stems in the fact that there was never any justice for the victims. To this day, there’s no Wikipedia entry on them, just for Lizzie. “No one was charged after Lizzie was acquitted. Of course, I happen to think Lizzie was guilty.”

Dziedzic is one of a trio of older women who have spent decades passionately researching and blogging about all things Lizzie. To them, the murder house is an in-situ crime scene in which to explore and theorize, to maybe even be the one to crack the case. They appreciate the history more than the possibility that ghosts linger.

Lizzie Borden scholar and collector Faye Musselman has been riveted by the Lizzie story since 1969. Her blog, Tattered Fabric: Fall River’s Lizzie Borden, highlights her own 52 years of research. In an interview, she points out that in the early days of the home’s operation as a B&B, co-owners Donald Woods and Lee-Ann Wilber began to capitalize on a booming interest in paranormal matters, but sees Zaal’s endeavors as a bridge too far. “It’s a whole different pot of stew. It [will no longer be] an edifice, the mecca people go to to stand in the same place where this historical, classic, unsolved crime took place and to feel the residue of interest in it and roam around freely. You can put together things: Yes, that’s where [Andrew] hung his Prince Albert coat; yes, that’s the door Bridget came through. But now it’s a carnival, with a lot of rides. Get your ticket in the ticket booth.”

A third member of the trio, Stefani Koorey, who blogs at lizzieandrewborden.com, declined to participate in this article.

Competitiveness seems to spur the women to uncover new material. “Look how old the case is,” says Dziedzic. “Any nugget becomes valuable.” Rivalry can be healthy, but in this instance has become too intense. The trio’s history includes harassment protection orders, a jail stay, and public-facing taunts on social media. Their investigations, however, have led to gems like discovery of Emma Borden’s photo album, Lizzie’s passport application for the European tour she took two years before the murder, and rare photographs of Lizzie’s contemporaries. Dziedzic has written and performed in reenactments, and all three have engaged in deep, innovative thought about motive and manner. But still, the crime is unsolved.

The house where the elder Bordens were murdered is now at a key point in its life. Will the narrative of Lizzie Borden become one of mysterious knocks, spectral voices on tape, spirit orbs? A YouTuber trying to capture a vengeful ghost wiping her hatchet, and Andrew and Abby Borden howling their horrific fates?

These options seem perhaps disrespectful.

Under the previous owners, compassion for Andrew and Abby was still part of the house’s infrastructure. When I first visited in 2016, tour guide Colleen Johnson would only talk facts in the house. We literally stepped outside to talk conjecture, onto the porch where vintage milk cans tacitly recalled the police’s testing of the family milk to see if poison had been used the day before the murders.

But the owners were not above some gallows humor. The gift shop sold “blood-spattered” Lizzie bobbleheads and coffee mugs with images of the two corpses on it. A sign above the steep staircase read, “Don’t forget to duck. At least two people have lost their heads in this house.” And the web is flooded with photographs of people posing campily on the replica of the sofa where Andrew Borden met his demise, or lying face-down on the floor upstairs where Abby fell. A ouija board was available for guests to use, too.

In an interview, Zaal dismisses the concerns and states that his ownership will improve things for the house. “We’re making a lot of changes to how the business runs and what we offer guests,” he says. He says he wants to “export” Lizzie to those who can’t visit Fall River, meaning an emphasis on online content. “Lizzie Borden needs to adapt and move into a different century if it’s going to appeal to a new generation.”

Change can be complex. Lee-Ann Wilber was, all agree, a wonderful custodian of the house and its lore. Shockingly, her death was announced on social media on June 1, four days after the house had been sold—and on the anniversary of Lizzie Borden’s death in 1927. Wilber, who had wrapped her life around Lizzie’s story, now joined her in death at age 50.

But not so fast.

Wilber, in a coma on life support, actually held on for four more days, succumbing on June 5. While angry accusations were lobbed in the Lizzie community about the premature announcement, Dziedzic believes that Wilber, who had a macabre sense of humor, would have been amused. “Nobody would’ve gotten a bigger kick out of that than Lee-Ann,” she says.

Zaal now sleeps above the gift shop, in the rebuilt barn where Wilber often spent the night to keep an eye on doings at the B&B. Does he think that she will now join the spirits who possibly remain? “I did sense a presence in the house but not in the barn. I like to think she’s in a better place than the tiny barn up there,” he says.

Erika Mailman is the author of The Murderer’s Maid: A Lizzie Borden Novel, which tells Bridget’s side of the story and has a modern-day narrative with characters staying at the B&B. Mailman stayed in Bridget’s room overnight and got a terrible nightmare out of it.