Born into Bondage

Despite denials by government officials, slavery remains a way of life in the African nation of Niger

Lightning and thunder split the Saharan night. In northern Niger, heavy rain and wind smashed into the commodious goatskin tent of a Tuareg tribesman named Tafan and his family, snapping a tent pole and tumbling the tent to the ground.

Huddling in a small, tattered tent nearby was a second family, a man, a woman and their four children. Tafan ordered the woman, Asibit, to go outside and stand in the full face of the storm while holding the pole steady, keeping his tent upright until the rain and wind ceased.

Asibit obeyed because, like tens of thousands of other Nigeriens, she was born into a slave caste that goes back hundreds of years. As she tells it, Tafan’s family treated her not as a human, but as chattel, a beast of burden like their goats, sheep and camels. Her eldest daughter, Asibit says, was born after Tafan raped her, and when the child turned 6, he gave her as a present to his brother—a common practice among Niger’s slave owners. Asibit, fearful of a whipping, watched in silence as her daughter was taken away.

“From childhood, I toiled from early morning until late at night,” she recalls matter-of-factly. She pounded millet, prepared breakfast for Tafan and his family and ate the leftovers with her own. While her husband and children herded Tafan’s livestock, she did his household chores and milked his camels. She had to move his tent, open-fronted to catch any breeze, four times a day so his family would always be in shade. Now 51, she seems to bear an extra two decades in her lined and leathery face. “I never received a single coin during the 50 years,” she says.

Asibit bore these indignities without complaint. On that storm-tossed night in the desert, she says, she struggled for hours to keep the tent upright, knowing she’d be beaten if she failed. But then, like the tent pole, something inside her snapped: she threw the pole aside and ran into the night, making a dash for freedom to the nearest town, 20 miles across the desert.

History resonates with countless verified accounts of human bondage, but Asibit escaped only in June of last year.

Disturbing as it may seem in the 21st century, there may be more forced labor in the world now than ever. About 12.3 million people toil in the global economy on every continent save Antarctica, according to the United Nations’ International Labour Organization, held in various forms of captivity, including those under the rubric of human trafficking.

The U.S. State Department’s annual report on trafficking in persons, released in June, spotlighted 150 countries where more than a hundred people were trafficked in the past year. Bonded laborers are entrapped by low wages in never-ending debt; illegal immigrants are coerced by criminal syndicates to pay off their clandestine passage with work at subminimum wages; girls are kidnapped for prostitution, boys for unpaid labor.

The State Department’s report notes that “Niger is a source, transit, and destination country for men, women and children trafficked for the purposes of sexual exploitation and forced domestic and commercial labor.” But there is also something else going on in Niger—and in Chad, Mali and Mauritania. Across western Africa, hundreds of thousands of people are being held in what is known as “chattel slavery,” which Americans may associate only with the transatlantic slave trade and the Old South.

In parts of rural West Africa dominated by traditional tribal chieftains, human beings are born into slavery, and they live every minute of their lives at the whim of their owners. They toil day and night without pay. Many are whipped or beaten when disobedient or slow, or for whatever reasons their masters concoct. Couples are separated when one partner is sold or given away; infants and children are passed from one owner to another as gifts or dowry; girls as young as 10 are sometimes raped by their owners or, more commonly, sold off as concubines.

The families of such slaves have been held for generations, and their captivity is immutable: the one thing they can be sure of passing on to their children is their enslavement.

One of the earliest records of enslaved Africans goes back to the seventh century, but the practice existed long before. It sprang largely from warfare, with victors forcing the vanquished into bondage. (Many current slave owners in Niger are Tuareg, the legendary warlords of the Sahara.) The winners kept slaves to serve their own households and sold off the others. In Niger, slave markets traded humans for centuries, with countless thousands bound and marched to ports north or south, for sale to Europe and Arabia or America.

As they began exercising influence over Niger in the late 19th century, the French promised to end slavery there—the practice had been abolished under French law since 1848—but they found it difficult to eradicate a social system that had endured for so long, especially given the reluctance of the country’s chieftains, the major slave owners, to cooperate. Slavery was still thriving at the turn of the century, and the chances of abolition all but disappeared during World War I, when France pressed its colonies to join the battle. “In order to fulfill their quotas each administrator [in Niger] relied on traditional chiefs who preferred to supply slaves to serve as cannon fodder,” writes Nigerien social scientist Galy Kadir Abdelkader.

During the war, when rebellions broke out against the French in Niger, the chieftains once again came to the rescue; in return, French administrators turned a blind eye to slavery. Following independence in 1960, successive Nigerien governments have kept their silence. In 2003, a law banning and punishing slavery was passed, but it has not been widely enforced.

Organizations outside Niger, most persistently the London-based Anti-Slavery International, are still pushing to end slavery there. The country’s constitution recognizes the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 4: “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms”), but the U.N. has done little to ensure Niger’s compliance. Neither has France, which still has immense influence in the country because of its large aid program and cultural ties.

And neither has the United States. While releasing this year’s trafficking report, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice reminded Americans of President Bush’s plea in a 2004 speech for an end to human trafficking, but the U.S. Embassy in Niger professes little on-the-ground knowledge of chattel slavery there. In Washington, Ambassador John Miller, a senior adviser to Rice who heads the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons section, says, “We’re just becoming aware of transgenerational slavery in Niger.”

The Nigerien government, for its part, does not acknowledge the problem: it has consistently said that there are no slaves in Niger. Troubled by the government’s denials, a group of young civil servants in 1991 set up the Timidria Association, which has become the most prominent nongovernmental organization fighting slavery in Niger. Timidria (“fraternity-solidarity” in Tamacheq, the Tuareg language) has since set up 682 branches across the country to monitor slavery, help protect escaped slaves and guide them in their new, free lives.

The group faces a constant battle. Last March, Timidria persuaded a Tuareg chief to free his tribe’s 7,000 slaves in a public ceremony. The mass manumission was widely publicized prior to the planned release, but just days before it was to happen, the government prevailed upon the chief to abandon his plan.

“The government was caught in a quandary,” a European ambassador to Niger told me. “How could it allow the release when it claimed there were no slaves in Niger?”

The flight from paris to Niamey, Niger’s capital city, takes five hours, much of it above the dun-hued sweep of the Sahara in northern Africa. We land in a sandstorm, and when the jet’s door opens, the 115-degree heat hits like a furnace’s fiery blast. Niamey is a sprawl of mud huts, ragtag markets and sandy streets marked by a few motley skyscrapers. I pass a street named after Martin Luther King Jr., but the signpost has been knocked askew and left unrepaired.

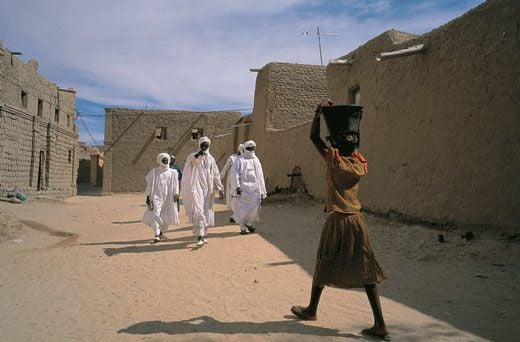

Nigeriens walk with the graceful lope of desert dwellers. The city reflects the country, a jumble of tribes. Tall, slim Tuareg men conceal all but their hands, feet and dark eyes in a swath of cotton robes and veils; some flaunt swords buckled to their waists. Tribesmen called Fulanis clad in conical hats and long robes herd donkeys through the streets. The majority Hausa, stocky and broad-faced, resemble their tribal cousins in neighboring Nigeria.

Apart from the rare Mercedes Benz, there is hardly any sign of wealth. Niger is three times bigger than California, but two-thirds of it is desert, and its standard of living ranks 176th on the United Nations’ human development index of 177 countries, just ahead of Sierra Leone. About 60 percent of its 12 million people live on less than $1 a day, and most of the others not much more. It’s a landlocked country with little to sell to the world other than uranium. (Intelligence reports that Saddam Hussein tried to buy yellowcake uranium from Niger have proved “highly dubious,” according to the State Department.) A2004 U.S. State Department report on Niger noted that it suffers from “drought, locust infestation, deforestation, soil degradation, high population growth rates [3.3%], and exceedingly low literacy rates.” In recent months, 2.5 million of Niger’s people have been on the verge of famine.

A Nigerien is lucky to reach the age of 50. The child mortality rate is the world’s second worst, with a quarter of all children dying under the age of 5. “Niger is so poor that many people perish daily of starvation,” Jeremy Lester, the European Union’s head of delegation in Niamey, tells me.

And Niger’s slaves are the poorest of the poor, excluded totally from the meager cash economy.

Clad in a flowing robe, Soli Abdourahmane, a former minister of justice and state prosecutor, greets me in his shady mud-house compound in Niamey. “There are many, many slaves in Niger, and the same families have often been held captive by their owners’ families for centuries,” he tells me, speaking French, the country’s official language, though Hausa is spoken more widely. “The slave masters are mostly from the nomadic tribes—the Tuareg, Fulani, Toubou and Arabs.”

A wry grin spreads across his handsome face. “The government claims there are no slaves in Niger, and yet two years ago it legislated to outlaw slavery, with penalties from 10 to 30 years. It’s a contradiction, no?”

Moussa Zangaou, a 41-year-old member of Parliament, says he opposes slavery. He belongs to a party whose leaders say it does not exist in Niger, but he says he is working behind the scenes toward abolition. “There are more than 100,000 slaves in Niger, and they suffer terribly with no say in their destiny,” he tells me. “Their masters treat them like livestock, they don’t believe they are truly human.”

I’m puzzled. Why does the government deny there is slavery in Niger, and yet, in the shadows, allow it to continue? “It’s woven into our traditional culture,” Zangaou explains, “and many tribal chieftains, who still wield great power, are slave owners and bring significant voting blocs of their people to the government at election time.”

Also, the government fears international condemnation. Eighty percent of the country’s capital budget comes from overseas donors, mostly European countries. “The president is currently the head of the Economic Community of West African States,” Zangaou adds, “and he fears being embarrassed by slavery still existing in Niger.”

In the meantime, slaves are risking terrible beatings or whippings to escape and hide in far-off towns—especially in Niamey, with a population of 774,000, where they can disappear.

One afternoon, a Timidria worker takes me to Niamey’s outskirts to meet a woman he says is a runaway slave. With us is the BBC’s Niger correspondent, Idy Baraou, who is acting as my interpreter and sounding board.

We enter a maze of mud huts whose walls form twisting channels that lead deep into a settlement that would not appear out of place in the Bible. It houses several thousand people. As camels loaded with straw amble by, children stare wide-eyed at me while their parents, sprawled in the shade, throw me hard glances. Many have fled here from rural areas, and strangers can mean trouble in a place like this.

A woman comes out from a mud house, carrying a baby and with a 4-year-old girl trailing behind. Her name is Timizgida. She says she is about 30, looks 40, and has a smile that seems as fresh as her recent good fortune. She says she was born to slaves owned by fair-skinned Tuaregs out in the countryside but never knew her parents, never even knew their names; she was given as a baby to her owner, a civil servant. She was allowed to play with his children until she was 8, when she was yanked into the stark reality of captivity.

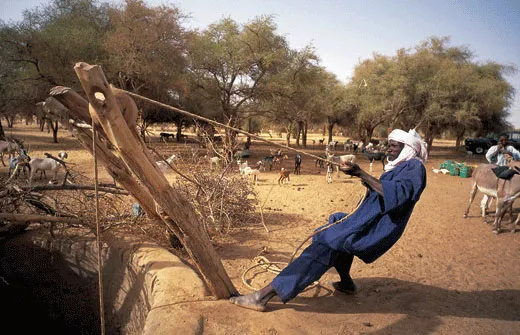

Her fate from then on was much the same as Asibit’s; she rose before dawn to fetch water from a distant well for her owner’s thirsty herds and his family, and then toiled all day and late into the night, cooking, doing chores and eating scraps. “I was only allowed to rest for two or three days each year, during religious festivals, and was never paid,” she tells me. “My master didn’t pay his donkeys, and so he thought why should he pay me and his other slaves?”

The spark in Timizgida’s eye signals a rebellious nature, and she says her owner and his family beat her many times with sticks and whips, sometimes so hard that the pain lingered for months. After one such beating three years ago, she decided to run away. She says a soldier took pity on her and paid her and her children’s bus fares to Niamey. “With freedom, I became a human being,” she tells me with a smile. “It’s the sweetest of feelings.”

Her smile grows wider as she points to her kids. “My children were also my master’s slaves, but now they’re free.”

Timizgida’s account echoes those I will hear from other slaves in far-off regions in a country where communications among the poor are almost nonexistent. But the president of Niger’s Human Rights Commission, Lompo Garba, tells me that Timizgida—and all other Nigeriens who claim they were or are slaves—is lying.

“Niger has no slaves,” Lompo says, leaning across his desk and glaring. “Have you seen anyone in Niger blindfolded and tied up?”

Niger’s prime minister, Hama Amadou, is equally insistent when we meet at his Niamey office, not far from the U.S. Embassy. He is Fulani and has a prominent tribal scar, an X, carved into his right cheek. “Niger has no slaves,” he tells me emphatically.

And yet in July 2003, he wrote a confidential letter to the minister of internal affairs stating that slavery existed in Niger and was immoral, and listing 32 places around the

country where slaves could be found. When I tell him I know about the letter—I even have a copy of it—the prime minister at first looks astonished and then steadies himself and confirms that he wrote it.

But still he denies that his country has slaves. “Try and find slaves in Niger,” he says. “You won’t find even one.”

As I leave for Niger’s interior to take up the prime minister’s challenge, I am accompanied by Moustapha Kadi Oumani, the firstborn son of a powerful Tuareg chieftain and known among Nigeriens as the Prince of Illéla, the capital of his father’s domain. Elegant, sharp-minded and with the graceful command that comes from generations of unchallenged authority, he guides us by SUV to Azarori, about 300 miles northeast of Niamey and one of more than 100 villages under his father’s feudal command.

Moustapha in boyhood was steeped in his tribal traditions, with slaves to wait on him hand and foot, but his exposure to their condition, and a few years studying in Italy and Switzerland, convinced him that no person should belong to another. Moustapha now works in the Department of Civil Aviation in Niamey, but he devotes much of his spare time working to end slavery in Niger and improve the living conditions of ordinary Nigeriens. In December 2003, he freed all ten of the slaves he had inherited in a public ceremony at Tahoua, about 110 miles from Azarori. On the government’s orders, police seized the audio- and videotapes of reporters and cameramen who were covering the event. “They didn’t want people to know,” says Idy, who was there for the BBC.

The number of slaves in Niger is unknown. Moustapha scoffs at a widely quoted Timidria survey in 2002 that put it at 870,363. “There was double counting, and the survey’s definition of a slave was loose,” he says. Anti-Slavery International, using the same data, counted at least 43,000 slaves, but that figure has also been questioned—as both too high and too low.

The countryside, facing a famine, looks sickly, and when the SUV pulls to the side of the road for a comfort stop, a blur of locusts clatter into the air from a stunted tree nearby. We arrive at Azarori (pop. 9,000) at midmorning as several men and children—all slaves, Moustapha says—herd goats to pasture.

A stooped old man in a conical hat and purple robe tells me that he has worked hard for his owner for no pay since he was a child. Another man, Ahmed, who is 49, says that Allah ordained that he and his family are to be slaves through the generations. (Niger is 95 percent Muslim.) When I ask him to quote that command from the Koran, he shrugs. “I can’t read or write, and so my master, Boudal, told me,” he says.

Like most of the slaves I would meet, Ahmed looks well fed and healthy. “Aslave master feeds his donkeys and camels well so they can work hard, and it’s the same with his slaves,” Moustapha says.

This may explain the extraordinary devotion many slaves insist they offer their masters in this impoverished nation, especially if they are not mistreated. I ask Ahmed how he would feel if his owner gave away his daughter. “If my master asked me to throw my daughter down the well, I’d do it immediately,” he replies.

Truly?

“Truly,” he replies.

Moustapha shakes his head as we sip the highly sugared bitter tea favored by the Tuareg. “Ahmed has the fatalistic mindset of many slaves,” he says. “They accept it’s their destiny to be a bellah, the slave caste, and obey their masters without question.”

We journey to another village along dirt roads, framed by a sandy landscape with few trees but many mud villages. At one of them, Tajaé, an 80-year-old woman named Takany sits at Moustapha’s feet by her own choice and tells how she was given to her owner as an infant. Her great-grandson, who looks to be about 6 years old, sits by her side. Like many other child slaves I see, he is naked, while the village’s free children wear bright robes and even jeans. The naked children I see stay close to their relatives, their eyes wary and their step cautious, while the clothed children stroll about or play chase.

The village chief, wearing a gold robe and gripping a string of prayer beads, asks Moustapha, as the son of his feudal lord, for advice. A man had recently purchased a “fifth wife” from a slave owner in the village, the chief says, but returned her after discovering she was two months pregnant. He wanted a new slave girl or his money back. Although Islam limits a man to four wives, a slave girl taken as a concubine is known as a “fifth wife” in Niger, and men take as many fifth wives as they can afford.

Moustapha’s face tightens in barely concealed anger. “Tell him he’ll get neither, and if he causes trouble, let me know.”

In late afternoon, we reach the outskirts of Illéla and enter wide, sandy streets lined with mud-house compounds. About 12,000 people live here, ruled by Moustapha’s father, Kadi Oumani, a hereditary tribal chieftain with more than a quarter of a million people offering fealty to him. “My ancestor Agaba conquered Illéla in 1678 and enslaved the families of warriors who opposed him,” Moustapha tells me. “Many of their descendants are still slaves.”

Moustapha has surveyed the families of the 220 traditional chieftains in Niger, known as royal families, and found that they collectively own more than 8,500 slaves whose status has not changed since their ancestors were conquered. “When a princess marries, she brings slaves as part of her dowry,” he tells me. He has caused trouble for his highborn family by opposing slavery, but shrugs when I ask if this worries him. “What worries me is that there are still slaves in Niger.”

Moustapha’s father sits on a chair in a mud-wall compound with a dozen chiefs perched cross-legged on the ground around him. Two dozen longhorn cattle, sheep and goats mill about, there for the Tuareg aristocrats to enjoy as a reminder of their nomadic origins. Kadi Oumani is 74 years old and wears a heavy robe and an open veil that reveals his dark, bluff face. Moustapha greets him with a smile and then leads me to the compound set aside for us during our visit.

For the next hour Moustapha sits serenely on a chair at the compound’s far end, greeting clan leaders who have come to pay their respects. A special visitor is Abdou Nayoussa, one of the ten slaves Moustapha freed 20 months ago. Abdou’s broad face marks him as a member of the local tribe conquered by Moustapha’s ancestor.

“As a boy I was chosen to look after the chieftain’s horses, feeding, exercising and grooming them,” he tells me. “I worked hard every day for no pay, was beaten many times and could never leave Illéla because I belonged to Moustapha’s family.” His eyes—which never once meet Moustapha’s—are dim with what I take to be pain. “At night I cried myself to sleep, thinking about my fate and especially the fate of the children I’d have one day.”

Abdou still works as the chieftain’s horse handler, for which he is given little pay, but he is now free to do what he wants. “The difference is like that between heaven and hell,” he tells me. “When I get enough money, I’m going to Niamey

and never coming back.”

As the sky darkens, we eat grilled lamb and millet. Nearby a courtier sings an ancient desert tune. Moustapha’s cousin Oumarou Marafa, a burly, middle-aged secondary school teacher, joins us. “He’s a slave owner and not ashamed of it,” Moustapha informs me.

“When I was younger, I desired one of my mother’s slaves, a beautiful 12-year-old girl, and she gave her to me as a fifth wife,” Oumarou tells me. “There was no marriage ceremony; she was mine to do with her as I wished.”

Did that include sex? “Of course,” he says. After a few years, he sent the girl away, and she married another man. But Oumarou still considers her his possession. “When I want to sleep with her, she must come to my bed,” he says without a hint of emotion.

I find this hard to believe, but Moustapha says it is true. “It’s the custom, and her husband is too scared to object,” he adds.

“There are many men in Illéla with fifth wives,” Oumarou goes on, even though the cost is about a thousand U.S. dollars, or three years’ pay for a laborer. “If you want a fifth wife and have the money, I can take you tomorrow to slave owners with girls for sale here in Illéla.”

I squirm at the thought. Late into the night Moustapha and I attempt to convince his cousin of slavery’s evil nature, trying to change his belief that slaves are a separate, lower species. “Try and understand the enormous mental pain of a slave seeing his child given away as a present to another family,” I tell him.

“You Westerners,” he replies. “You only understand your way of life, and you think the rest of the world should follow you.”

Next morning, Moustapha takes me to the 300-year-old mud-brick palace where his father, in a daily ritual, is meeting chiefs who have come to honor him. Inside, Kadi Oumani sits on a modest throne from which he daily delivers judgments on minor disputes, principally about land and marriages.

“There are no slaves in Niger,” he tells me.

“But I’ve met slaves.”

“You mean the bellah,” he says in his chieftain’s monotone. “They are one of the traditional Tuareg castes. We have nobles, the ordinary people and the bellah.”

Just before dawn the morning after, I set out with Idy, my translator, to drive north more than 125 miles deeper into the desert near Tamaya, the home of Asibit, the woman who says she escaped from her master during the storm.

There, we pick up Foungoutan Oumar, a young Tuareg member of Timidria, who will guide us across 20 miles of open desert to wells where he says slaves water their masters’ herds in the morning and late afternoon. Foungoutan wants to avoid meeting slave owners, especially Asibit’s former master, Tafan, who he says recently used his sword to lop off the hand of a man in a dispute. But it’s not necessarily Tafan’s anger we wish to sidestep. “If we go to the tents of the slave masters, they’ll know we’ve come to talk to their slaves, and they’ll punish them,” Foungoutan says.

The sand stretches to the horizon, and the sun already burns our skin even though it’s just eight o’clock in the morning. There is no one at the first two wells we visit. “The slaves have already gone with the herds,” Foungoutan says with a shrug. The third well, nudged by a cluster of trees, is owned by a man named Halilou, Tafan’s brother.

Six children are unloading water containers from donkeys. The younger children are naked. When they see us, they scream and bury their heads in the donkey’s flanks and necks. Shivering in apparent fear, they refuse to lift their heads or talk. Three women arrive balancing water containers on their heads, having walked the three miles from Halilou’s tents. They turn their faces away from us.

Soon a middle-aged man appears with a naked child by his side. His face clouds when he sees us. “My master said he’ll beat me if I talk to strangers,” he says. He warns the others not to tell their master about us.

With some coaxing he says their master’s name is Halilou and adds that they are all slaves in his camp. He says he has toiled for Halilou’s family since he was a child and has never received any money. Halilou has beaten him many times, but the man shrugs off more talk of punishment and refuses to give his name.

Another man arrives, and the two of them begin drawing water from the well, helped by five donkeys hauling on a rope attached to a canvas bucket. They pour the water into troughs for the thirsty cows, sheep and goats and then fill the containers. As the women lead thewater-laden donkeys back to their master’s tents, the two men and children herd the livestock out into the desert to graze on the shriveled grass and plants that grow there.

At Tamaya, a small village hemmed in by desert, we find Asibit at her usual spot in the bustling marketplace where robed Tuareg, Fulani, Hausa and Arabs buy and sell livestock, foodstuffs and swords. “Many of these men own slaves,” Foungoutan says. “I’ve reported them to the police, but they take no action against them.”

When Asibit reached Tamaya on the morning after the thunderstorm, she was led to Foungoutan, who took her to the police. She made a formal complaint that Tafan was a slave owner, and the police responded by rescuing her children, including the daughter presented to Halilou. But Asibit says they left her husband with Tafan.

Asibit squats in the shade, making a drink from millet and selling it for the equivalent of 10 cents. She smiles easily now. “You can’t understand what freedom is until you’ve been a slave,” she says. “Now, I can go to sleep when I want and get up any time I want. No one can beat me or call me bad names every day. My children and grandchildren are free.”

Freedom, however, is relative. For former slaves, the search for a place in Nigerien society is harsh. “Former slaves suffer extreme discrimination in getting a job, government services, or finding marriage partners for their children,” says Romana Cacchioli, the Africa expert for Anti-Slavery International, speaking by telephone from the group’s London headquarters.

The government is not likely to come forward to help exslaves on its own; to acknowledge ex-slaves would be to acknowledge slavery. And the government, lacking the power to confront the chieftains and fearing condemnation from the outside world, gives no signs of doing that.

Within Niger, Timidria remains the most visible force for change, but it, too, faces a long road: many Nigeriens say they do not support the antislavery cause because they believe the group’s president, Ilguilas Weila, has profited from his association with Western aid organizations. (Both he and Anti-Slavery International insist he has not.)

In April, the government arrested Weila and another Timidria leader in response to the failed release of the 7,000 slaves. Weila was freed on bail in June but is awaiting a ruling on whether there is enough evidence to try him. The charge against him amounts to fraud: he solicited funds overseas to fight slavery in his country, the government contends, but of course there are no slaves in Niger.