Brainpower and Brawn in the Mexican-American War

The United States Army had several advantages, but the most decisive was the professionalism instilled at West Point

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130716114138mexican-american-war-thumb.jpg)

Chapultepec Castle is not, by Mexican standards, particularly old. Though the 12th-century Toltecs named the 200-foot-high outcrop on which the castle stands the “hill of the grasshopper”—chapoltepec in Nahuatl, probably for the huge numbers of the insects found there—the castle itself wasn’t built until 1775, as a residence for Spain’s viceroy. It was converted to a military academy in 1833, which was the extent of its martial history until September 13, 1847, when two armies faced off there in the climactic battle of the Mexican-American War.

After more than a year and a dozen engagements on land and sea, the U.S. had yet to suffer a defeat. General Zachary Taylor had crossed the Rio Grande with an expeditionary force of a little more than 2,000 men and defeated much larger Mexican armies at Monterrey and Buena Vista. Winfield Scott, America’s most senior general and the hero of the War of 1812, had taken Veracruz with a brilliant amphibious assault and siege, and defeated Mexico’s caudillo and president Antonio López de Santa Anna at Cerro Gordo. Then he had taken Puebla, Mexico’s second-largest city, without firing a shot.

There are any number of reasons why the Americans dominated the fighting. They had better artillery in front of them (rockets, siege weapons and highly mobile horse-drawn howitzers that could fire canister—20 or more lead balls packed in sawdust and cased in tin, which turned the American six-pounder cannons into giant shotguns). They also had a stronger government behind them (in 1846 alone, the Mexican presidency changed hands four times). However, the decisive American advantage was not in technology or political stability, but in military professionalism. The United States had West Point.

Though neither Scott nor Taylor nor their division commanders learned the military art at the U.S. Military Academy, virtually every junior officer in the Mexican campaign—more than five hundred of them—had. Under Sylvanus Thayer, who became superintendent in 1817, and his protégé Dennis Hart Mahan, the academy became more than just a fine engineering school. In accord with legislation Congress passed in 1812, the course of studies at West Point required cadets to master all the skills not only of an officer, but of a private and a noncommissioned officer as well.

It made for a revolution in military education. Mahan, an advocate for turning the military into a profession equal to that of physicians or attorneys, had completed a fundamental study of the art of war, which he would publish in 1847. The first American professional military journals—the Army and Navy Chronicle, the Military and Naval Magazine and the Military Magazine—all started publication between 1835 and 1839.

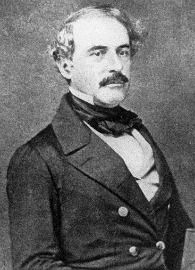

This environment produced the staff and line officers who accompanied Taylor across the Rio Grande and Scott from Veracruz to Chapultepec. One of them, Ulysses S. Grant (USMA Class of 1843), wrote, “A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican War.” Scott shared his “fixed opinion that but for our graduated cadets the war between the United States and Mexico might, and probably would, have lasted some four or five years with, in its first half, more defeats than victories falling to our share, whereas in two campaigns we conquered a great country and a peace without the loss of a single battle or skirmish.”

The academy graduates proved extraordinary in Mexico (and even more so in their subsequent careers in a far more bloody conflict). When Scott landed at Veracruz, his junior officers included not only Grant, but also Robert E. Lee (USMA 1829; commanding general, Army of Northern Virginia, 1862). Captain Lee led his division through the “impassible ravines” to the north of the Mexican position at Cerro Gordo and turned the enemy’s left flank. The path to Mexico City, over the 10,000-foot pass of Río Frío, was mapped by First Lieutenant P.G.T. Beauregard (USMA 1838; general, Army of the Mississippi, 1861) and First Lieutenant George Gordon Meade (USMA 1835; commanding general, Army of the Potomac, 1863). Captain (soon enough Major) Lee found the best route to the relatively undefended southwestern corner of Mexico City, through a huge lava field known as the pedregal that was thought to be impassible; American engineers—accompanied by First Lieutenant George McClellan (USMA 1846; commanding general, U.S. Army, 1861)—improved it into a military road in two days, under regular artillery fire. The Molino del Rey, a mill that Scott mistakenly thought was being converted into a cannon foundry during a cease-fire, was occupied, after some of the bloodiest fighting of the war, by Lieutenant Grant and First Lieutenant Robert Anderson (USMA 1825).

So it’s scarcely surprising that when the final attack on Chapultepec Castle began on that September morning in 1847, one of the columns was led by Lieutenant Colonel Joe Johnston (USMA 1829; commanding general, Army of Tennessee, 1863). Or that, when the Americans were pinned down after they’d fought to the top of the hill, Second Lieutenant Thomas J. Jackson (USMA 1846; lieutenant general and corps commander, Army of Northern Virginia, 1862), commanding two six-pounder cannon at the far left of the American line, rushed forward in support. As he did so, a storming party of 250 men reached the base of the castle wall and threw scaling ladders against the 12-foot-high fortification. There, Captain Lewis A. Armistead (USMA, 1838, though he never graduated; brigadier general, Army of Northern Virginia, 1863) was wounded; so was the officer carrying the regimental colors of the 8th Infantry, First Lieutenant James Longstreet (USMA 1842; lieutenant general, Army of Northern Virginia, 1862), which were then taken by Second Lieutenant George E. Pickett (USMA 1846; major general, Army of Northern Virginia, 1862). In an hour, the castle was taken.

And, in less than a day, so was Mexico’s capital. Jackson, who had been under fire for more than 12 hours, chased more than 1,500 Mexicans down the causeway that led into the capital “for about a mile…. It was splendid!” Grant, commanding a platoon-sized detachment, dragged a six-pound howitzer to the top of a church belfry, three hundred yards from the main gate to the city at San Cosmé, and put a withering fire on the Mexican defenses until he ran out of ammunition. A day later, Scott rode into the Grand Plaza of Mexico City at the head of his army. Though the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would not be signed until February of 1848, the battles of the Mexican-American War were over.

Not, however, the battle over the war’s narrative: its rationale, conduct and consequences. Los Niños Heroes—six cadets who from the Chapultepec military academy who refused to retreat from the castle, five of them dying at their posts and the sixth throwing himself from the castle wrapped in the Mexican flag—synthesize the Mexican memory of the war: brave Mexicans sacrificed by poor leadership in a war of aggression by a neighbor who, in one analysis, “offered to us the hand of treachery, to have soon the audacity to say that our obstinacy and arrogance were the real causes of the war.”

The enlargement of the United States of America by some 500,000 square miles, plus Texas, was certainly a valuable objective, but it’s uncertain that achieving it required a war, any more than the 800,000 square miles of the Louisiana Purchase did. Grant himself opined that the Mexican war was “the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.” Even more uncertain is the argument, voiced by Grant, among others, the American Civil War “was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican War.” The sectional conflict over the expansion of slavery might have been different without Monterrey, Cerro Gordo and Chapultepec, but no less pointed, and the Civil War no less likely—or less bloody.

However, it would have been conducted very differently, since the men who fought it were so clearly marked by Mexico. It was there they learned the tactics that would dominate from 1861 to 1865. And it was there they learned to think of themselves as masters of the art of war. That, of course, was a bit of a delusion: The Mexican army was no match for them. They would prove, tragically, a match for one another.

What the Mexican War created, more than territory or myth, was men. More than a dozen future Civil War generals stood in front of Chapultepec Castle in 1847—not just the ones already named, but First Lieutenant Simon Bolivar Bruckner (USMA 1844; brigadier general, Army of Central Kentucky, 1862), who fought alongside Grant at Molino del Rey and would surrender Fort Donelson to him in 1862; Second Lieutenant Richard H. Anderson (USMA 1842; lieutenant general, Army of Northern Virginia 1863); Major John Sedgwick (USMA 1837; major general, Army of the Potomac 1863), the highest-ranking Union Army officer killed during the Civil War; Major George B. Crittenden (USMA 1832; major general, Army of Central Kentucky, 1862); Second Lieutenant A.P. Hill (USMA 1846; lieutenant general, Army of Northern Virginia, 1863); and Major John C. Pemberton, (USMA 1837; lieutenant general, Army of Mississippi, 1862), who joined Grant in the steeple of the church at San Cosmé and defended Vicksburg against him 16 years later.

The Duke of Wellington spent his life denying he had ever said that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton. Much more apt to say that the Battle of Chapultepec was won on the parade grounds of West Point, and that the Battles of Shiloh, Antietam and Gettysburg were won—and lost—in the same place.

Sources

Alexander, J. H. (1999). The Battle History of the U.S. Marines. New York: Harper Collins.

Coffman, E. M. (1986). The Old Army: A Portrait of the Army in Peacetime, 1784-1898. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cullum, G. W. (1891). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy (3 volumes). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Dufour, C. L. (1968). The Mexican War: A Compact History. New York: Hawthorn Books.

Elliott, C. W. (1939). Winfield Scott: The Soldier and the Man. New York: Macmillan.

Freeman, D. S. (1991). Lee: An Abridgment by Richard Harwell of the Pulitzer-Prize Winning 4-Volume Biography. New York: Scribners.

Grant, U. (1990). Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. NY: Library of America.

Jones, W. L. (2004). Generals in Blue and Gray, Volume II. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

McDermott, J. D. (1997). Were They Really Rogues? Desertion in the Nineteenth Century US Army. Nebraska History , 78, 165-174.

McFeely, W. S. (1981). Grant. New York: W.W. Norton.

Millett, A. R. (1991). Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ramsey, A. C. (1850). The Other Side: Or Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the United States . New York: John Wiley.

Robertson, J. I. (1997). Stonewall Jackson: The Man, the Soldier, the Legend. New York: Macmillan.

Rohter, L. (1987, Dec 18). Chapultepec Park: Mexico in Microcosm. New York Times .

Smith, J. E. (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Stevens, D. F. (1991). Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Thomas, E. M. (1995). Robert E. Lee: A Bioography. NY: W.W. Norton.

Weigley, R. (1967). History of the United States Army. NY: Macmillan.