The Brief History of “Americanitis”

More than a century ago, the experts thought that Americans worked too hard, putting their collective health at risk

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/cb/ffcb53a9-9618-48fc-913b-4de3dd0930ee/ae-for-businessmen-1072x720.jpg)

Too much stress, too little sleep, rushed meals, technology that seems to change faster than we can begin to keep up with. If those complaints sound familiar, chances are they’d have resonated with your great-great grandparents too.

More than a century ago, Americans had much the same concerns, and some leading thinkers and medical practitioners even took it a step further. They suggested that the country’s legendary work ethic and go-getter spirit might be a form of mental illness that they called “Americanitis.”

The origins of the now-forgotten term are fuzzy, but it was most likely coined by a foreign observer. An 1882 medical journal article attributed it to a visiting English scientist; the 1891 book Power Through Repose, by Annie Payson Paul, credited a German physician. William James, the famous American psychologist, became identified with the term, sometimes even credited as its inventor, after reviewing Paul’s book.

The idea that the pace of American life might have adverse health effects was hardly new. But the invention of “Americanitis” gave it a veneer of medical legitimacy, suggesting such familiar, and very real, ailments as arthritis, bronchitis, and gastritis.

Some writers saw Americanitis—“the hurry, bustle and incessant drive of the American temperament,” as the psychiatrist William S. Sadler defined it—as a cause of disease, responsible for high blood pressure, hardening of the arteries, heart attack, nervous exhaustion, and even insanity. To others, though, it was a disease it its own right, a consequence of the country’s incessant busyness and a close relative of neurasthenia, another fashionable diagnosis of the day.

Recent technological marvels like electric lights and wireless radio also took some of the blame. The former stood accused of extending the working day to all hours and robbing Americans of sleep; the latter, of turning long-distance communication, once limited to letters, into a frantic exercise in false urgency—a charge that, generations later, would also be leveled against e-mail.

The Journal of the American Medical Association acknowledged the condition as early as 1898, linking it in one article to the increased noise level in industrialized America. “Who shall say how far the high-strung, nervous, active temperament of the American people is due to the noise with which they choose to surround their daily lives?” the author asked.

It wasn’t long before Americanitis had spread beyond the medical journals and into everyday vocabulary, shorthand for a deadly mix of hurry and worry. Orison Swett Marden, a self-help author and editor of Success magazine, and Elbert Hubbard, the flamboyant “Sage of East Aurora,” were two of the many popular writers to address the subject.

Marden devoted a chapter to “The Cure for Americanitis” in his book, Cheerfulness as a Life Power. “How quickly we Americans exhaust life!” he wrote. “Hurry is stamped in the wrinkles of the national face.” The “cure,” as he saw it, was to stop worrying so much. “Instead of worrying about unforeseen misfortune,” he advised, “set out with all your soul to rejoice in the unforeseen blessings of all your coming days.”

Hubbard attributed the disease to “an intense desire to ‘git thar’ and an awful feeling that you cannot.” He advised readers to “cut down your calling list, play tag with the children, and let the world slide. Remember that your real wants are not many—a few hours work a day will supply your needs—then you are safe from Americanitis and death at the top.”

Theodore Dreiser raised the question “Americanitis—Can It Be Cured?” in The Delineator, a women’s fashion magazine he edited. “The morning paper gives us a daily list of deaths by suicide, apoplexy, and insanity,” he lamented, “men in the prime of life rushing into eternity, desperate because they are left behind in the race, or driven mad by the rush of the business world.” He recommended learning to relax the muscles.

Marion Harland, a widely read advice columnist and cookbook author, singled out eating too fast as the greatest “sin” of Americanitis. In her syndicated “School for Housewives” feature, she suggested women use family meals as an opportunity to reform their husbands, instruct their children, and “set the example of eating leisurely and masticating thoroughly.”

Soon it was difficult to find a physical ailment or societal ill that Americanitis couldn’t be held responsible for. In 1907, newspapers reported that the Chicago meatpacking millionaire Nelson Morris had died of the disease. In 1910, William T. Sedgwick, a prominent MIT professor, blamed it for Americans’ worsening eyesight. “Everyone who lives here long enough gets it,” he said. In 1912, a Harvard professor blamed it for the nation’s rising divorce rate. In 1922, the chairman of the psychology department at the University of Iowa, said jazz music and flappers were both “manifestations” of the disease.

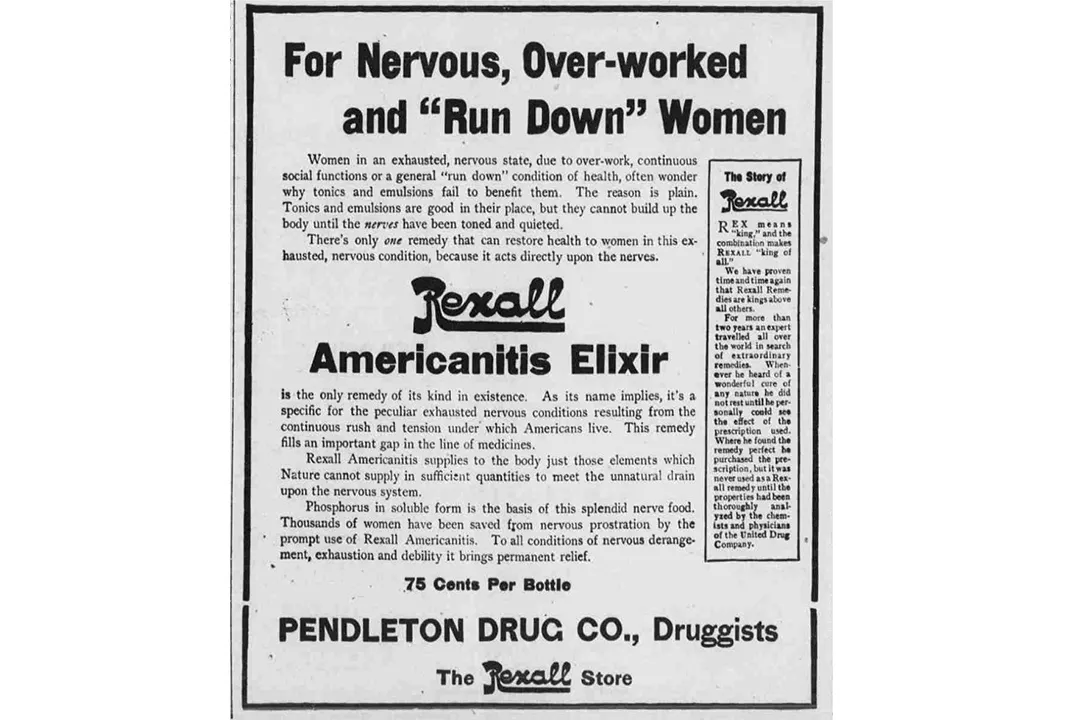

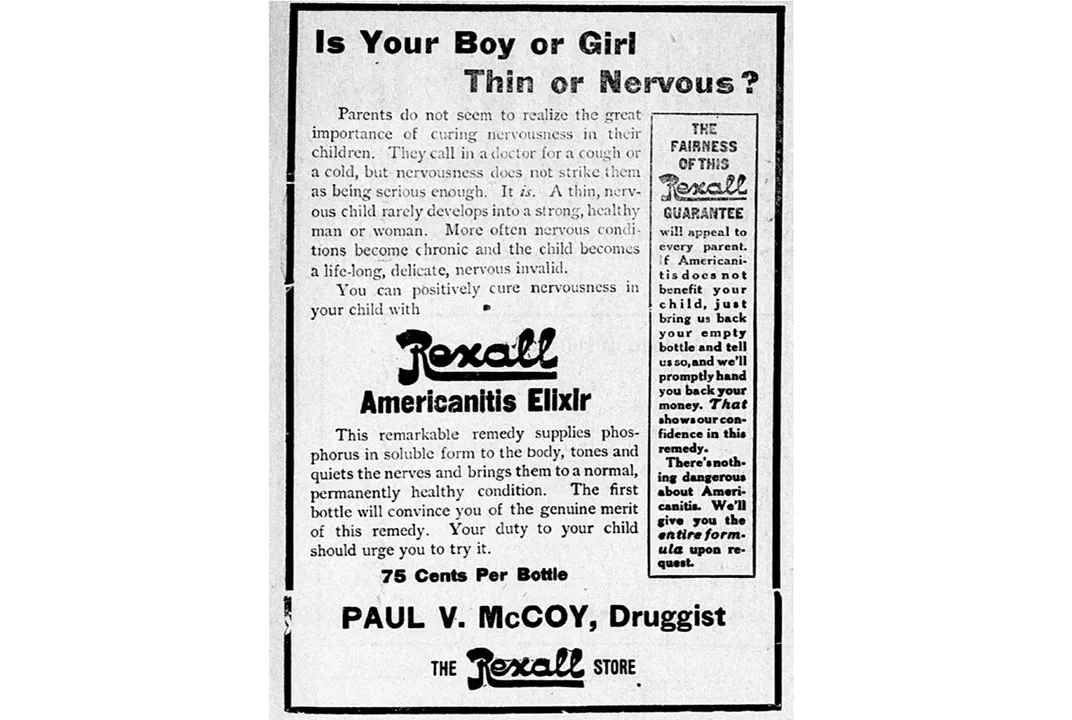

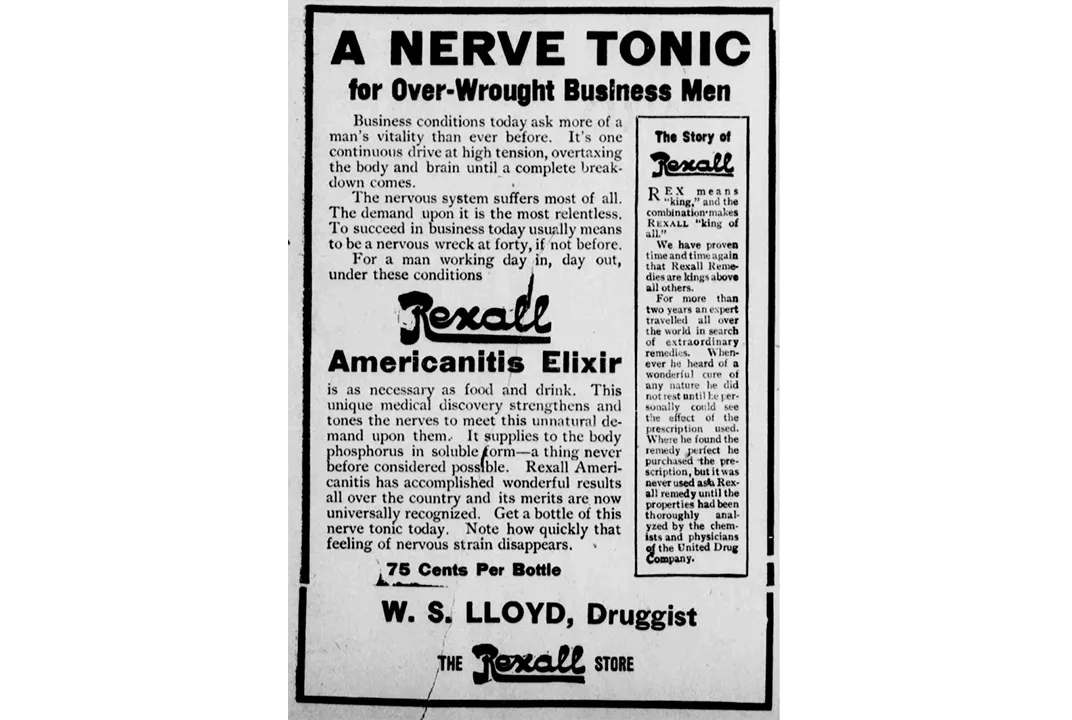

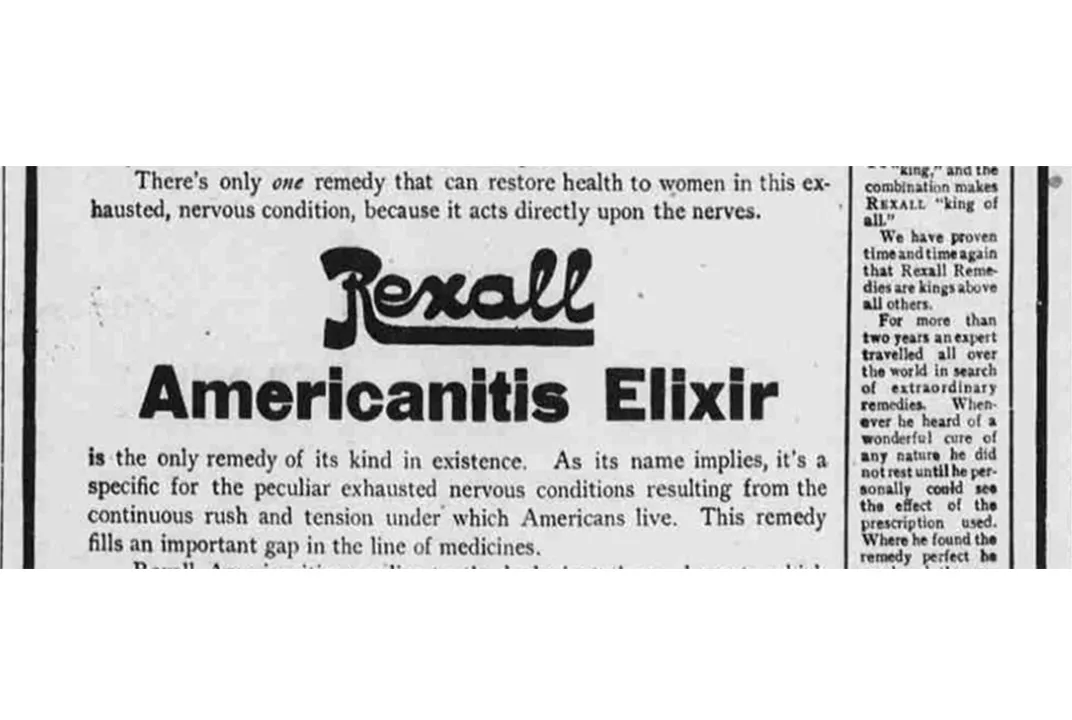

Meanwhile, the go-getters of the patent-medicine world knew an opportunity when they saw one. Rexall introduced its Americanitis Elixir, which it promoted for every member of the household short of the family dog. Some ads promised relief to “over-wrought business men,” others to “nervous, over-worked and ‘run-down’ women.” Still others suggested parents administer it to their “thin or nervous” children, so that none would become a "life-long, delicate, nervous invalid." Among other ingredients, the elixir contained 15 percent alcohol and a little chloroform.

If elixirs didn’t help, electricity was another option. Noting the “many devious remedies” for Americanitis then on the market, a 1900 textbook on electo-therapeutics proclaimed that,“The one remedy really indicated is most often some selected form of electric current.” As the author explained, “There is nothing equal to electricity to clear up the mind, brush away the cob-webs, or soothe it, re-invigorate it and re-establish its normal workings.” For more squeamish sufferers, a manufacturer of reclining chairs offered its product as the answer.

But Americanitis marched on. In 1925 Time magazine and newspapers across the country reported on psychiatrist Sadler’s estimate that it claimed 240,000 lives a year, primarily men between the ages of 40 and 50, who were dying at a far greater rate than their peers in Europe.

Sadler had been on the case for decades, lecturing about Americanitis and eventually writing a book on the topic. He had no medical miracle to offer and, in fact, didn’t seem to believe one was needed. “A game of baseball, a round of golf or a long walk in the country will do more to cure Americanitis than all the medicines the doctors can hand out,” he said in one talk. Writing in The New York Times, he suggested midday naps, more fruits and vegetables, and simply less worry.

Soon, however, Americanitis had lost its standing as a serious diagnosis, if indeed, it ever was one. It disappeared from the medical journals and from the popular press as well.

By the Great Depression of the 1930s, it was all but forgotten. With unemployment at record levels, few Americans could complain of overwork. There was no shortage of worry, but little reason to hurry. For millions of American go-getters, the going and getting had come to an end.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)