A Brief History of the Nickel

In honor of the coin’s 150th anniversary, read up on how the nickel came to be minted

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/31/ff31381b-1e94-4ec3-8994-ddd8f1547f45/istock_000001150873_large.jpg)

The nickel wasn't always worth five cents. In 1865, the U.S. nickel was a three-cent coin. Before that, “nickel cents” referred to alloy pennies.

It turns out that even the name “nickel” is misleading. “Actually, nickels should be called 'coppers,'” says coin expert Q. David Bowers. Today's so-called nickels are 75 percent copper.

Those aren't the only surprises hidden in the history of the nickel. The story of America's five-cent coin is, strangely enough, a war story. And 150 years since it was first minted in 1866, the modest nickel serves as a window into the symbolic and practical importance of coinage itself.

To understand how the nickel got its name, you have to go back to an era when precious metals reigned supreme. In the 1850s, coins of any real value were made of gold and silver. In the event of a financial crisis—or worse, the collapse of a government—precious metal coins could always be melted down. They had intrinsic value.

But in the spring of 1861, southern states began to secede, and Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President. Soon shells were falling on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. America was in crisis, and so was its currency. “The outcome of the Civil War was uncertain,” says Bowers, an author of several books on coin history. Widespread anxiety led to an important side-effect of war. “People started hoarding hard money, especially silver and gold.”

Coins seemed to vanish overnight, and the U.S. Mint couldn't keep up with demand. “The United States literally did not have the resources in gold and silver to produce enough money to meet the needs of the country,” says Douglas Mudd, the director of the American Numismatic Association. “Even the cent was disappearing.” In the South, this problem was even worse. The limited supply of gold and silver was needed to purchase supplies from abroad, which meant the Confederacy relied almost exclusively on paper currency.

Minting new coins might not seem like a priority in a time of war. But without coinage, transactions of everyday life—buying bread, selling wares, sending mail—become almost impossible. One Philadelphia newspaper reported that the local economy had slowed to a crawl in 1863, citing that some storekeepers had to cut their prices “one to four cents on each transaction” or refuse to sell products outright because they were unable to get a hold of money.

Mudd puts the problem in more familiar terms. “It's like, all of a sudden, not being able to go to 7-Eleven because [the cashier] can't make change,” he says. “And if [they] can't make change, the economy stops.”

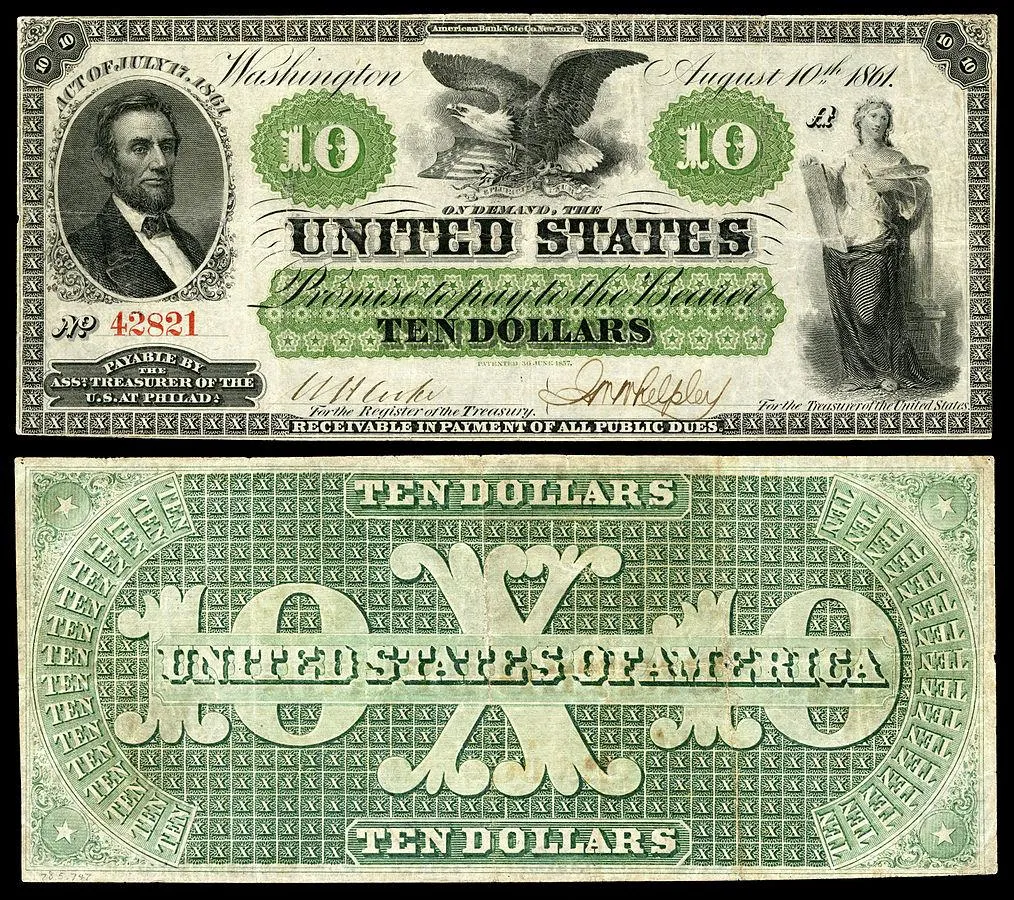

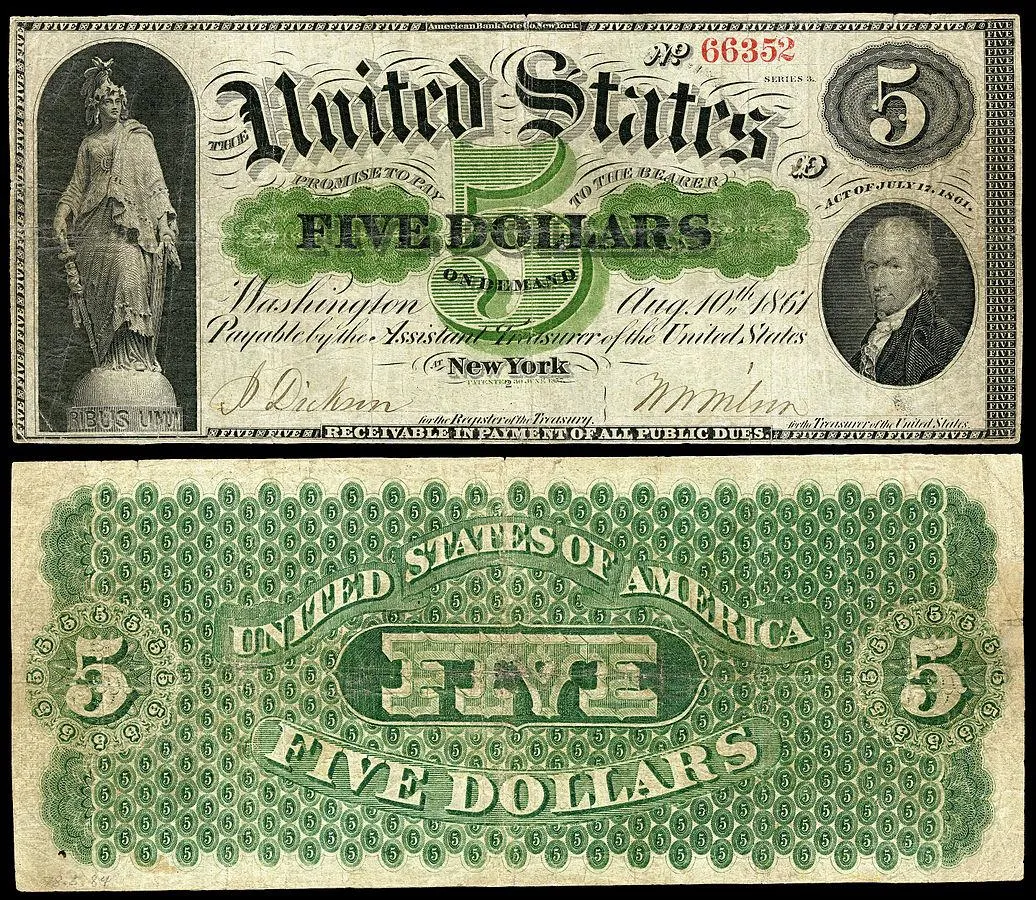

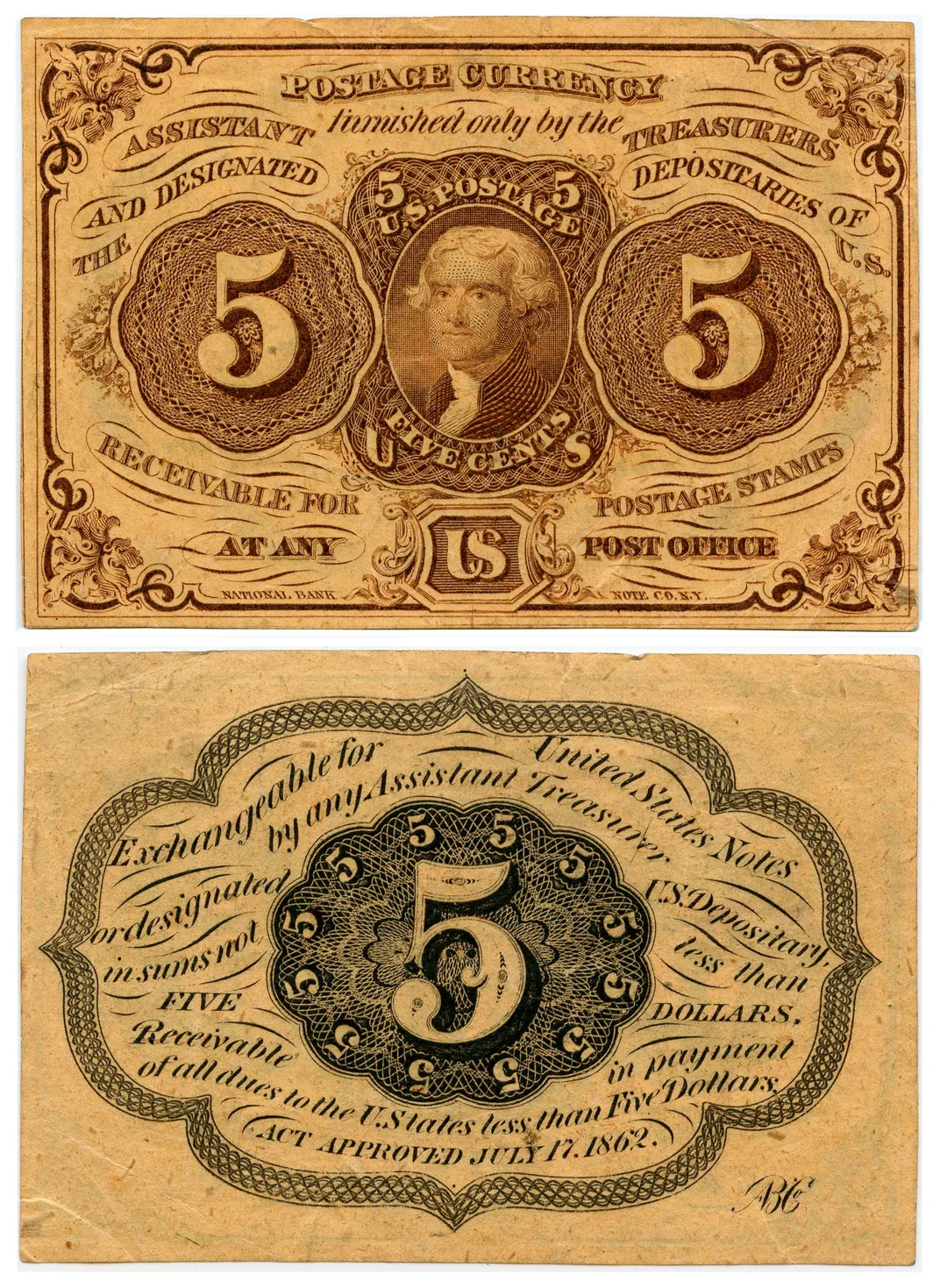

It was in this economic vacuum that the United States tried a series of monetary experiments. In 1861, the government began paying Union soldiers with “Demand Notes”—also known as “greenbacks.” Meanwhile, stamps were declared legal tender for small purchases; a round metal case was developed to keep them intact. “It looked like a coin with a window on it,” says Mudd.

For the duration of the war, the American economy puttered along with all kinds of competing currency. Even private banks and businesses were releasing their own notes and coins. Shopkeepers could give coins, stamps or bills as change. The war finally ended in 1865, but it took many months for precious metals to trickle back into circulation. “It's not until after the Civil War that coin production resumes at full capacity,” says Mudd.

As the United States turned its attention to rebuilding, not all metals were scarce. War production had expanded America's industrial capacity, and nickel was available in huge quantities. The advantage of nickel lay in what it wasn't. It wasn't scarce, which meant the government could print millions of coins without creating new shortages. And it wasn't a precious metal, so people wouldn't hoard it.

In fact, some cent coins had already been minted using nickel—and as one Pennsylvania newspaper pointed out, “the hoarding of them is unwise and injudicious.” There's no sense in hoarding a coin whose value comes from a government guarantee.

Only after a bizarre 1866 controversy about paper money, however, did nickel coins finally conquer everyday life. At the time, the National Currency Bureau (later called the Bureau of Engraving and Printing) was led by a man named Spencer Clark. He was tasked with finding a suitable portrait for the five-cent note. Clark's selection was a proud-looking man with dark eyes and a thick white beard. The public was not amused.

“He put his own image on there,” says Mudd. “There was a major scandal.”

“Clark put his own head on the currency without any authority whatever,” declared an angry letter to the New York Times. Reporting by the Times depicted Clark's bearded portrait as an assault on the dignity of American money. Another letter-writer chimed in: “It shows the form of impudence in a way seldom attempted before. It is not the first time, however, that men have made a strike for fame, and only achieved notoriety.”

While legislators were making speeches in Congress denouncing Clark's portrait, an industrialist named Joseph Wharton was busy prodding legislators to find an alternative to paper money. In the early years of the war, Wharton had bought up nickel mines in New Jersey and Pennsylvania, so his suggestion should come as no surprise. He wanted coins to be made out of nickel.

Two months later, five-cent notes were quietly retired. And as Philadelphia's Daily Evening Bulletin reported in May of 1866, a new coin was to immediately take its place. “The President [Andrew Johnson] has approved a bill to authorize the coinage of five cent pieces, composed of nickel and copper,” said the article. “There are to be no more issues of fractional notes of a less denomination than ten cents.”

The new coin was decorated with a shield, the words “In God We Trust,” and a large “5,” surrounded by a star and ray design. That year, the government minted a whopping 15 million five-cent nickels—more than 100 times the number of silver half-dimes minted the year before.

As far as the future of the nickel was concerned, the timing was perfect. The postwar economy began to gather steam again. “The supply was there, and the demand was there,” says Mudd. “People wanted coins.”

The nickel caught on for a few reasons. First of all, after years of coin shortages, nickels flooded the economy. Nearly 30 million were printed in 1867 and 1868. “The nickel was the coin from 1866 to 1876,” says Bowers. Even after that, as dimes and quarters rose in prominence, nickels were the coin of convenience. Bottles of Coca-Cola, which entered the marketplace in 1886, cost a nickel for 73 years.

The shield nickel was produced until 1883, when it was replaced due to manufacturing issues by the “Liberty Head” nickel. The decades that followed saw a succession of new designs, starting in 1913 with the Buffalo nickel and followed in 1938 by the initial Jefferson nickel. (Ironically, during World War II, nickel was so essential for war production that nickels were produced without any nickel.) The most recent update, in 2006, revised Jefferson's image from a profile to a frontal portrait.

In the 20th century, one other shift cemented the nickel as an indispensable coin of the realm: the rise of coin-operated machines. Nickels were the ideal denomination for vending machines, jukeboxes, and slot machines. It also cost five cents to attend a “nickelodeon”—that is, a nickel theater. (Odeon comes from the Greek word for theater.) “Nickels went into the mainstream,” says Bowers.

Nickels have come full-circle since their roots in the gold and silver shortages of the Civil War. One hundred and fifty years ago, coins made of nickel seemed convenient because they were made of cheap metals. These days, nickel and copper prices are high, and our beloved 5-cent coin costs around 8 cents to produce. Maybe it's time to bring back the five-cent note.