The British Museum Was a Wonder of Its Time—But Also a Product of Slavery

A new book explores the little-known life and career of Hans Sloane, whose collections led to the founding of the British Museum

:focal(530x326:531x327)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/9d/cb9d0694-33c9-498c-8654-90eb808af544/british_museum.jpg)

Public museums offer the opportunity for wonder, awe and discovery. They're places where anyone can learn about the giant stone calendar of the Aztecs, the mysterious death of a famous explorer, the medicinal use of milk chocolate. They promote science and the arts, stimulate conversations on difficult topics like racism, and give people a sense of shared heritage.

Many public museums, though, also obfuscate the truth of their origins. It’s easy for a placard to include information on what an object is, and even how it fits into the broader narrative of history or science. It’s much harder to describe, in detail, where an object came from and who may have suffered through its creation—and its acquisition.

Historian James Delbourgo tackles this dilemma in his new book, Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum. The narrative follows the life of Englishman Hans Sloane, born in Ulster in 1660 to a working-class family in the part of Catholic Ireland that had just been colonized by Protestant Brits. Sloane works his way up the social ladder, becoming a physician and traveling to Jamaica for his work. Over the course of his life, Sloane collected tens of thousands of items which became the basis for what is today known as the British Museum. Along the way, he participated in—and profited from—the Atlantic slave trade, a part of the British Museum’s storied legacy that many continue to overlook.

Smithsonian.com recently spoke with Delbourgo about why Sloane matters today, some of the more bizarre objects in his collections (including a Chinese ear tickler), and how museums can reckon with the darker side of their origins.

Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum

In this biography of 17th-century physician and collector Hans Sloane, James Delbourgo recounts the story behind the creation of the British Museum, the first free national museum in the world.

Why should we remember Hans Sloane?

[He created] the first truly public museum anywhere in the world. The British Museum originated in the 18th century and Hans Sloane was the person who, when he died in 1753, set up his will to ask the British Parliament to buy his collection for £20,000 and set up a public museum that anybody, whether they were British or from outside Britain, would be able to enter free of charge.

Of course, what they had in mind at the time was mainly dignitaries and foreign scholars from other parts of Europe. For several decades there were quite a few curators who were not comfortable with the idea that anybody could look at the collections and study them. Curators didn’t like the idea that lower orders of society were going to come in and get their hands on the collections. They had a great deal of class anxiety and believed learning was a genteel privilege. It took a long time into the 19th and even 20th century to accept that.

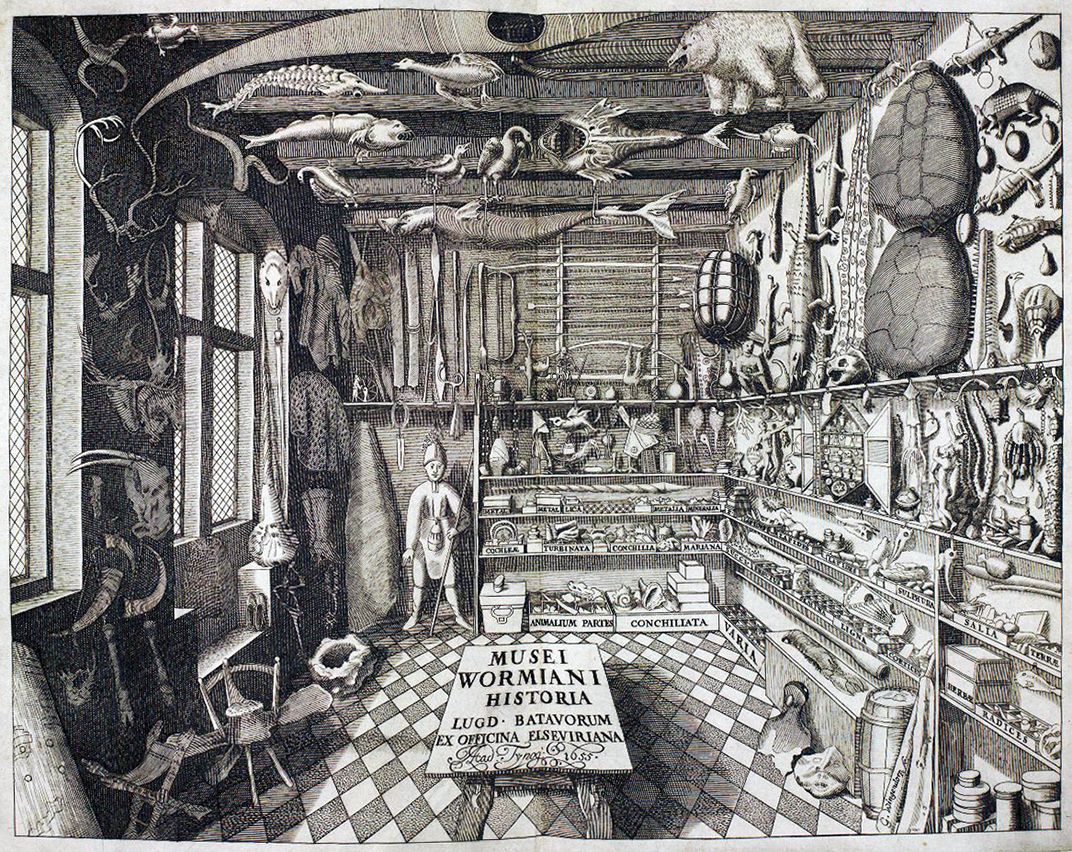

Before Sloane’s time, collections were often privately owned “wonder cabinets.” How does he fit into that trend?

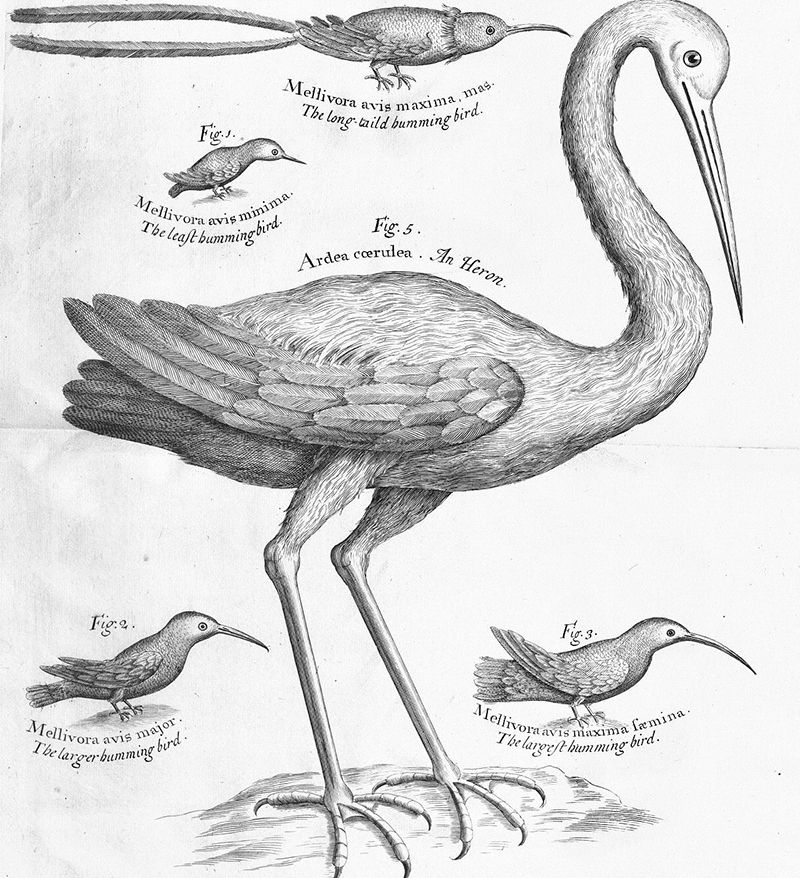

Sloane has always been a challenge for people to interpret. Is he a figure of the Enlightenment, when knowledge became more systematic? Or is he a figure who harkened back to older traditions of collecting wonders and marvels and strange things, the figure the Enlightenment had to get rid of? He created catalogues of fossils, minerals, fish, birds, and a category that he called “miscellaneous objects” that he didn’t think fit in his other catalogues, things we would call ethnographic artifacts. Yet he is the person who creates the first public freely accessible public collection.

[His collection] can look very modern or completely out of date. If you go into the Natural History Museum in London they still have Sloane’s massive herbarium, thousands of plants collected by many people. That collection is still used as a working botanical collection. But he collected things such as a coral hand—a formation of coral spontaneously in the shape of a human hand—a shoe made of human skin, ear ticklers from China. He collected all sorts of strange, interesting, exotic curiosities that today would be part of an anthropology collection, but his form is natural history. The book tries to get us to understand this is where the British Museum comes from. It is really a cabinet of curiosities.

How did he impact other scientists and their methods of collecting?

The influence Sloane had was rather negative. People would look back from the 19th and 20th centuries and say, “Why on earth did he collect that strange object? Why did he spend 10 shillings on the vertebrae of an ox bisected by an oak branch? What was he thinking?” I think this is one of the reasons the story of Sloane has got lost for such a long time. What he was doing was looked on in the 19th century as “this is what we need to move on from.”

The big story with Sloane is that this form of universalism, the idea of collecting books and plants and manuscripts and curious artifacts [into one collection] was rejected in the 19th century. Modern knowledge was specialization.

But the idea of a cabinet of curiosities has really come back in recent years. The general public has rediscovered the cabinet of curiosities and delighted in its strangeness, its wondrousness, as a kind of relief from the more rigid category of, this is an archaeology museum, this is a geology museum, this is art history. People came to realize there is an extraordinary power in breaking down some of our boundaries and categories and juxtaposing things that suggest many emotions, many questions, that open up how different parts of the natural and artificial world relate to each other.

Sloane spent a year-and-a-half on Jamaica, where slaves were brought to work on plantations. What role did slavery play in his work?

There’s no doubt that slavery played a foundational role in Sloane’s life and in the career that led to the British Museum. These things are not widely known but are very well documented. He went to Jamaica and spent almost a year-and-a-half there, he worked as a plantation doctor, so he’s part of slavery and keeping the system going. [His book] A Natural History of Jamaica is entirely enabled by slavery.

When he comes home he marries a Jamaican heiress, so money comes into the family coffers from slave plantations for many years. He has many correspondences throughout the Caribbean and West Africa, slave traders send him specimens, and he collects clothing worn by slaves, nooses and whips used to punish and execute runaways. He had skin specimens, skull specimens, he was part of this early scientific generation already interested in trying to work out is there a physical basis for racial difference? There is both a financial and intellectual resonance of slavery that is foundational to Sloane’s success and his intellectual pursuits.

What did he collect from the slaves themselves?

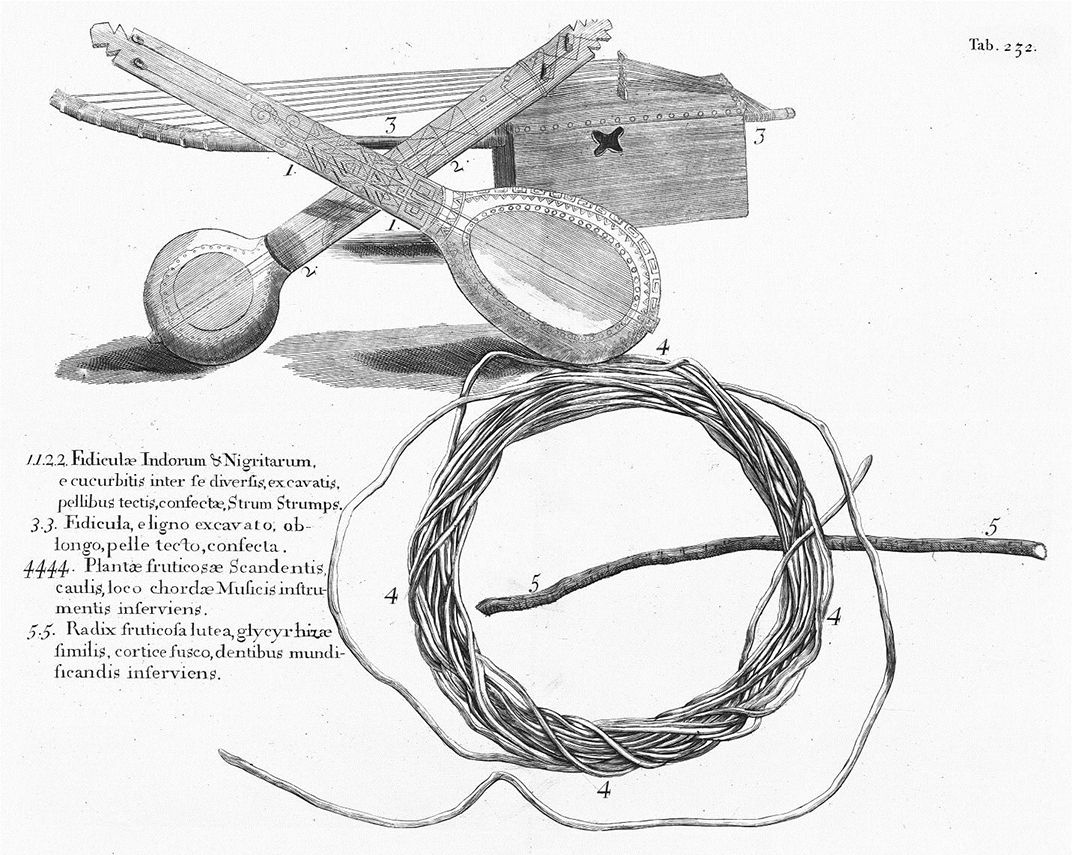

One of the things that Sloane collected in Jamaica were stringed instruments played by enslaved Africans on the island. It’s a very remarkable thing he did to collect these instruments. He not only collected these instruments, but collected and had written down the music which slaves played, which he witnessed when he was there. These things are what we would call cultural artifacts: they told you something about Jamaica, something about its cultural life. But they were also, for him, natural specimens. He paid a lot of attention to the fact that they were made from gourds and calabashes and strung with horse hairs.

He goes into the provision grounds that slaves use to grow their own food, guinea corn and sorghum and okra and rice and he brings some of those specimens back to London. Why is he so interested? Because for him it’s the enslaved population who is a living link to the deeper natural and botanical history of the island.

What does Sloane’s involvement in slavery mean for the legacy of the British Museum?

I think it’s been elusive for far too long. My hope is that museums, the British Museum of course included, tell the stories of where they come from and where their collections come from. They can help the public reckon with the contradictions of history. We’re talking about one of the great institutional legacies of the Enlightenment that is worth championing and defending today. But I think museums have to join in reckoning with where these collections have come from.

Any museum implies wealth, institution building, objects from many parts of the world. Museums have an obligation to the public to tell the stories of those relationships to allow the public to understand the past much better. We need to know all the different forces that made our great institutions and I think we can do better in providing some context.

It wasn’t just curiosity that drove Sloane to collect, but also business prospects. How did the two tie together?

We tend to think of museums, perhaps especially natural history museums, as existing in something of a commercial void. But in fact, Sloane’s intellectual projects were also deeply commercial. The English, the Spanish, the French were all competing to get exotic new drugs, foodstuffs in this global competition for commercial advantage.

These are commercial networks, these are the means by which he puts many collections together. He never goes to China, Japan, or India, or North America, yet he has a large collection from all of these places because he has correspondence with and is paying many journeymen, often very obscure people finding themselves in these parts of the world. This story is about the commercial prowess of the 18th-century British Empire.

What was Sloane’s motivation for writing the British Museum into his will?

[Sloane] was not simply a very wealthy physician, but a publicly prominently one. Not just healing the royal family, but consulted by Westminster, the Crown, on matters of national health. On whether there should be a quarantine against plague on ships, or if we should take up the practice of inoculation for diseases like smallpox. He has a very strong sense of his own public position and responsibility in order to make pronouncements on behalf of the public good. I think that’s the place where the impulse to create a free public museum whose collections can be used for study, for commercial benefit [comes from]. I think the importance of him being a physician and collector drove together this purpose which he was able to realize.

What would Sloane think of the British Museum today?

He would not recognize it. If he was in the British Museum today he would find it rather disorienting because in the 19th century, archaeological discoveries profoundly deepened Europe’s understanding of historical time—Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Rome.

Sloane is a very interesting form of encyclopedism, which is not about progress as such, or the development over time. It’s not even structured by political divisions, racial divisions. Instead we have this foundation, which is: God created the world in all its magnificence, let us understand what he created and use it for our benefit.

It’s a rather different mentality. The challenge for us to realize is while we might think about different cultures, civilizations, deep time, archeology, excavation—none of that was operative in Sloane’s form of trying to know about the whole world. Sloane gives us a foundational approach that led to the British Museum, but it was overhauled and changed when knowledge itself changed in the 19th century.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)