Building the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial

For those working behind the scenes on the King memorial, its meaning runs deep

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/MLK-Memorial-front-631.jpg)

In early August, as the finishing touches are being made to the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial in Washington, D.C., Deryl McKissack waits in a trailer on the premises. “You could not pick a better site,” says the engineer, of the four-acre plot alongside the capital’s Tidal Basin. “He is sitting on a direct axis between the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials—so between two presidents. That is a spot for a king, right?” Surprised by the pun that rolls off of her tongue, McKissack splits into laughter.

“I never thought of what it would be like the day of dedication. I always thought about just being a part of something great,” says McKissack, 50, president and CEO of McKissack and McKissack, an architectural and engineering firm. The memorial opens to the public August 22, and the official dedication ceremony is set for August 28. “It is sinking in for me now,” she says. (Editor's Note: Due to Hurricane Irene, the dedication ceremony was postponed indefinitely.)

The memorial for King has certainly been a long time in the making. In the mid-1980s, a few members of Alpha Phi Alpha, the oldest intercollegiate fraternity for African Americans, presented the idea to the brotherhood’s board of directors. (King became an Alpha in 1952 while studying theology at Boston University.) It was not until the fall of 1996, though, that the Senate and House of Representatives passed joint resolutions to finally authorize the building of a memorial honoring the civil rights leader. In 1998, President Bill Clinton signed the resolution, and by December 1999, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Foundation was accepting design proposals. The foundation’s panel of judges reviewed over 900 designs, submitted by architects, designers and students from 52 countries. Ultimately, an entry by San Francisco’s ROMA Design Group was chosen.

From there, the foundation worked tirelessly to secure the memorial’s high-profile site near the National Mall and raise money. In 2006, Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin was selected to be the Sculptor of Record and contribute the centerpiece of ROMA’s design, a statue of King. A year later, McKissack’s involvement became official. Her firm—with Turner Construction, Tompkins Builders and Gilford Corporation—was hired as the design-build team that would take the memorial from concept to reality.

For McKissack, this job is a culmination of work done by generations of her family. Today, she is among the fifth generation in her family to work in construction and architecture. The first generation, Moses McKissack, came to the United States from West Africa in 1790 as a slave and learned the trade of building from his master, William McKissack. Moses taught his skills to his son, who passed them on to Deryl’s grandfather, Moses III. In 1905, Moses III and his brother Calvin, both of whom earned a degree in architecture through international correspondence courses, founded a firm called McKissack & McKissack in Nashville. Under Moses III’s lead, the McKissacks made a name for themselves. They designed educational facilities for the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, and, in the 1940s, built the 99th Pursuit Squadron Airbase in Tuskegee, Alabama. At $5.7 million, the airbase was the largest federal contract that had ever been awarded to an African American architect. Moses III even served as an adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on national housing problems.

Deryl’s father, William Deberry McKissack, took over the business in 1968, building churches, hospitals and college dormitories and academic buildings. “He had three girls, and he told us to go to school and marry someone to come run his business,” says Deryl. But, ultimately, it was the women in the family that carried on the legacy.

Deryl and her sisters were drafting at age 6 and their father was using their drawings by the time they were 13. “I know I worked on the library at Fisk University and then on the men’s dormitories at Tennessee State,” Deryl recalls. All three went to Howard University, and Deryl and her twin sister, Cheryl, studied architecture and engineering. When William suffered a stroke the very weekend the twins graduated, his wife, Leatrice, took control of the company. One of the notable projects under her “reign,” as Deryl puts it, was the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where King was assassinated. Today, Cheryl runs the original company—the oldest African American-led firm in the country.

In 1990, Deryl started a branch in Washington, D.C., with just $1,000. “There was only one building under construction in D.C. at 17th and K,” she says. “But I figured it was just me. There was nowhere I could go but up.”

With offices now in seven U.S. cities, McKissack & McKissack has been involved in the design, construction or restoration of several Washington landmarks, among them, the U.S. Treasury Building, the Washington Nationals’ stadium and the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. For two years, McKissack courted the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Foundation, assisting in any way she could, before being appointed contractor. “I just felt like my ancestors and everybody after me would be very proud about having a hand in this,” she says.

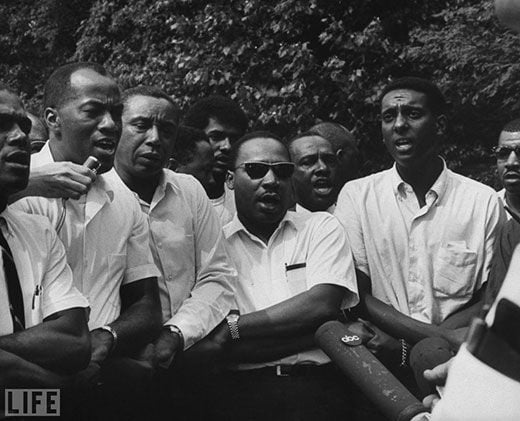

Like McKissack, senior project manager Lisa Anders, who oversees the day-to-day construction, is equally passionate about the personal meaning of the memorial. A Washington native, Anders says that her mom and grandmother walked the four miles from the house she now lives in to the Lincoln Memorial to hear King deliver his “I Have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963. Sunday, August 28, 2011 was chosen as the dedication day since it is the 48th anniversary of the March on Washington. “My grandmother turned 90 this month, and for her to be able to know that I am involved in this project has been special,” says Anders.

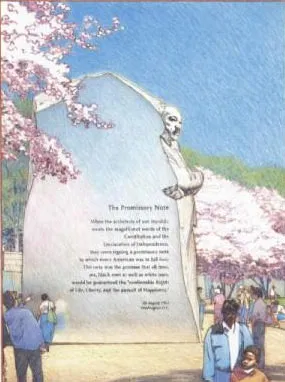

The concept for the memorial is actually rooted in a line from Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” The main entrance starts out wide and gradually funnels through a 12-foot wide opening in a “Mountain of Despair,” carved from sand-colored granite.

“The symbolic meaning behind that is to give the visitor the experience of feeling like going through a struggle,” says Anders. “If you can imagine a large crowd here, everyone is trying to get through to see the memorial.”

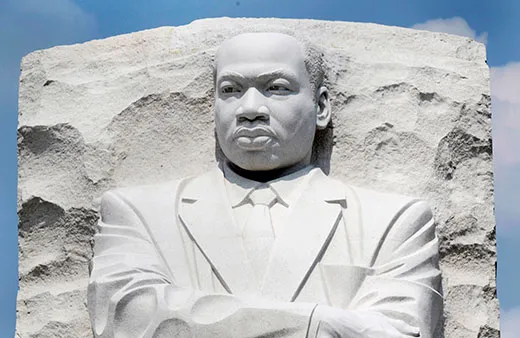

Then, through the Mountain of Despair, closer to the Tidal Basin, is a 30-foot-tall “Stone of Hope,” made to appear as if it was pulled from the mountain. Lei’s sculpture of King emerges from the side of the stone facing the water. His depiction of King, suited and standing, arms crossed with a stern expression on his face, is realistic, right down to the veins bulging on his hands.

“People who knew Dr. King personally, all of them look at it and say, ‘That’s him,’ ” says Anders. She has given several advance tours, including one for me. Earlier in the day that I visited, Stevie Wonder had come to touch the face of the sculpture. The day before, some Tuskegee Airmen walked the grounds. Thousands of visitors are expected to attend the dedication ceremony and many more in the weeks to follow.

A 450-foot dark granite wall bows like a parenthesis around the Stone of Hope, and inscribed on it are 14 quotations spanning King’s career—from the Montgomery bus boycotts in Alabama in 1955 to the last sermon he gave at the National Cathedral in Washington, just four days before his assassination in 1968. The Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Foundation assembled a group of historians, including Clayborne Carson, keeper of the King papers at Stanford University, to help decide on a selection of statements that speak to the themes of hope, democracy, justice and love. “Until we reach a point where the world realizes Dr. King’s dream fully, those quotes will be relevant to future generations,” says Anders. “The foundation’s goal was to make this a living memorial.”

The cherry blossom trees that bloom around the Tidal Basin in the spring are a popular draw for tourists, and over 180 additional trees—which peak, coincidently, around the April 4 anniversary of King’s assassination— were incorporated into the memorial. “They really make this place come alive,” says Anders.

Walking through the memorial, I see why Anders calls the site a “freebie” for a designer. The monument’s strengths are compounded by the powerful company it keeps. Passing through the Mountain of Despair, one can see the Jefferson Memorial, and then to the east is the Washington Monument.

Yet, as McKissack points out, the King memorial has a different message from the rest of the National Mall, with its tributes to presidents and war heroes. “I think this memorial is a piece of us as Americans that has not been captured before,” she says. “Love and peace and humanity—we have aspects of that around the Mall, but his whole memorial is about that. You can’t walk away from here not feeling it.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)