Burr, Ogden and Dayton: The Original Jersey Boys

Known as much for their troubles as their successes, these childhood friends left their mark on early American history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jersey-Boys-Ogden-Burr-Dayton-631.jpg)

In recent years Northern New Jersey has spawned famous groups of friends—the Four Seasons, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Tony Soprano’s gang—but at the nation’s founding, another posse of boys from North Jersey captured both the bright promise and the grimy underside of the new American republic.

Aaron Burr, Jonathan Dayton and the brothers Aaron and Matthias Ogden grew up together in Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth), then stormed across the nation, hell-bent on winning power and wealth. They found plenty of both, along with their share of troubles.

Their high-water mark came in 1803, when Vice President Burr presided over a U.S. Senate in which Dayton and Aaron Ogden were the members from New Jersey. But they also knew bitter humiliations: Burr was indicted for murder in two states. He and Dayton were charged with treason. In his old age, Aaron Ogden went to prison for debt, while Dayton never escaped rumors that he was a smuggler and swindler. Only Matthias Ogden avoided such calamities. He died at age 36.

They were boys of fortunate birth. Burr arrived in 1756, the same year his father was president of the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton). Dayton was born in 1760, the year after his father, a merchant, led New Jersey troops in the British capture of Quebec from France. The Ogdens were born in 1754 (Matthias) and 1756 (Aaron); their father was speaker of the colonial assembly and a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765.

Yet their privileges were tempered. Burr’s parents died before he was 3. He and his sister were taken in by an uncle and his wife, the former Rhoda Ogden. Their crowded household included Aunt Rhoda’s brothers, Matthias and Aaron Ogden. Dayton, a neighbor and two years younger still, rounded out their group.

They filled their days with sailing, fishing and crabbing. The Ogden brothers were large and powerful, while Dayton grew to a considerable height. Yet Burr, small and slender, was the leader. Independent from the start, he ran away from home twice. At 10, he signed on as cabin boy on a New York merchantman until his uncle retrieved him.

At War

Matthias Ogden and the precocious Burr attended Princeton together. As the Revolutionary War began in 1775, they volunteered to join Benedict Arnold’s daring winter invasion of Canada. Ogden was wounded before the attack on Quebec City that December, while Burr’s courage in the doomed American assault became legendary. After Ogden returned home to recuperate (and married Dayton’s older sister, Hannah), the friends pitched back into war.

Burr’s star rose quickly. As a 21-year-old lieutenant colonel, he commanded a regiment at the sweltering battle of Monmouth in June 1778, where he suffered heatstroke. His health damaged, Burr left the army the following year.

Ogden also became colonel, serving at Monmouth and at Fort Ticonderoga in New York. In 1780, British raiders captured him and Capt. Jonathan Dayton while sleeping at an Elizabethtown tavern, but Matthias was not done with war. After a prisoner exchange, he joined the American forces that cornered Cornwallis at Yorktown in the summer of 1781. But it was his younger brother, Maj. Aaron Ogden, who won glory in the attack on British defenses.

In 1782, Matthias Ogden won Washington’s approval for a scheme worthy of the Scarlet Pimpernel. He proposed to set fire to the outlying districts of New York City, then abduct Prince William Henry, the future King William IV, from his quarters there. The British blocked the plot when they destroyed Ogden’s boats.

Dayton’s military record was less gaudy. He began the war as paymaster in his father’s battalion, while whispers placed him amid the illegal smuggling between Elizabethtown and the British in New York.

In the New Republic

In peacetime, the Jersey Boys leapt at the great opportunities before them. They were distinguished veterans with Princeton degrees. They knew the right people. And they were determined to succeed.

Dayton started fastest, serving as the youngest delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, when he was 26 years old. Elected as a Federalist to the House of Representatives, he became speaker from 1795 to 1799. In the late 1790s, when the United States teetered on the brink of war with France, Dayton was named brigadier general. A British diplomat recalled him as “a great rake” who confided that “he thought a reward should be offered for the discovery of a new pleasure.”

Drawing on his family’s wealth, Dayton led syndicates that speculated in lands in Ohio and beyond, deals that often carried a whiff of fraud and self-dealing. Matthias Ogden and Burr gave legal advice on his deals, and all of the Jersey Boys invested in them. Though one contemporary called Dayton “an unprincipled speculator, and crafty politician,” Dayton lent his name to the city founded on his Ohio lands.

Matthias Ogden, too, greeted peace with energy. In addition to his law practice and western investments, he won the New York-Philadelphia mail contract, owned a stagecoach line and built both a tannery and a mint. In 1791, however, yellow fever extinguished his bright promise.

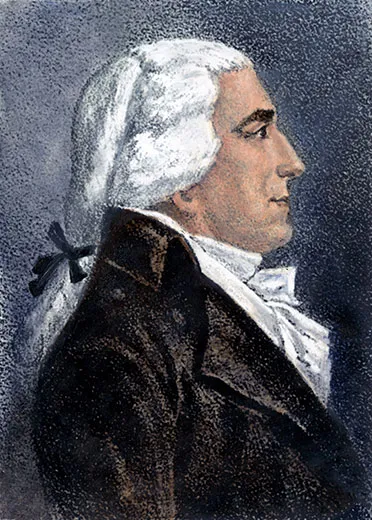

Aaron Ogden started his law practice in New Jersey, while Burr built his in New York City. Burr entered politics as the only non-Federalist among the Jersey Boys. He became New York State’s attorney general, then United States senator in 1791. By the turn of the century, he was the foremost Northern figure in the Republican Party led by Thomas Jefferson.

Burr maintained friendships among Federalists and Republicans alike, which led both to mistrust him. Of the Republicans, a friend observed that “they respect Burr’s talents, but they dread his independence. They know, in short, he is not one of them.” Friendship was stronger than party for the Jersey Boys. When Burr emerged as the leading Republican candidate for vice president in 1796, the Federalist Dayton was suspected of scheming to get his boyhood friend elected.

Burr’s perceived independence led him to the threshold of the presidency four years later—and began his slide to political oblivion. At the time, each state chose electors who cast two votes for president. The candidate with the highest vote total became president so long as he had a majority; the runner-up became vice president.

The system foundered in 1800, when the Republicans tagged Jefferson for president and Burr for vice president. To elect both men, all Republican electors should have cast a vote for Jefferson, while all but one should have cast their second vote for Burr. That would have placed Jefferson first and Burr second. But the balloting was bungled, leaving Jefferson and Burr in a tie. The election shifted to the House of Representatives in March 1801.

Federalist congressmen supported Burr for president as the lesser of two evils. Though he continued to support Jefferson’s candidacy, Burr said he would accept the office if the House chose him. Emboldened, Federalists backed Burr through 35 deadlocked votes in the House, until he instructed them not to. Two ballots later, Jefferson prevailed.

The ordeal irretrievably soured feelings between Burr and the new president, a wound only partially assuaged in 1803, when Dayton and Aaron Ogden served in the Senate over which Burr presided. Jefferson froze Burr out of both patronage and governing, then dropped him from the Republican ticket for 1804. That spring, trying to repair his fortunes, Burr ran for governor of New York against another Republican. He lost.

Caught in a downward spiral, Burr moved decisively to accelerate it. He learned that Alexander Hamilton, the former secretary of the Treasury, had referred to him as “despicable.” Burr demanded a retraction or satisfaction on the field of honor. Hamilton chose the field of honor. They met on July 11, 1804, in Weehawken, New Jersey, just 15 miles from Elizabethtown. Both men lost: Hamilton his life, Burr his political future.

Within days, Vice President Burr was in flight from New York. Within weeks, he had been indicted for murder in both New York and New Jersey.

Empire

In this desperate situation, Burr turned to his boyhood friends. He retained Aaron Ogden to defend him in the New Jersey murder case. And for the most audacious adventure of his life, Burr turned to Dayton.

Burr’s new plan ripened after he left the vice presidency in March 1805. In eight months of journeying through the American West, he began scheming with Gen. James Wilkinson, the traitorous head of the U.S. Army. With American troops, or with private adventurers, Burr proposed to invade Spanish Florida, Texas and Mexico. Simultaneously, he believed, the French-speaking residents of New Orleans and the recent Louisiana Purchase would revolt against American rule. Once in control of New Orleans, Burr expected the West to join a new empire that would girdle the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Keys to Central America.

Dayton was Burr’s chief aide. He introduced Burr to friends through the West. He met with British and Spanish diplomats to offer Burr’s assistance in leading the secession of western lands. Neither did Burr forget the two sons of his old friend Matthias Ogden: George Ogden became the scheme’s banker; in late 1806, Peter Ogden carried critical instructions from Burr and Dayton to the army chief.

When Wilkinson betrayed Burr, the plan swiftly unraveled. Although Burr intended to lead more than 1,000 adventurers down the Mississippi River, only 100 materialized. He was arrested above Natchez and hauled to Richmond to stand trial for treason. A separate indictment, handed up in the summer of 1807, accused Dayton, too.

Burr won his freedom in a landmark trial before Chief Justice John Marshall, a victory that cut off the case against Dayton. Aaron Ogden then squelched the New Jersey indictment stemming from the duel with Hamilton, freeing Burr to sail to Europe to seek British support in liberating Spain’s American colonies.

Steamboats and Interstate Commerce

After Burr’s debacles, he and Dayton could hardly run for public office, but Aaron Ogden won a term as New Jersey’s governor in 1812. The three surviving friends turned their attentions to steamboats, the technological wonder of the era.

In 1807, Robert Fulton unveiled the first viable steamboat design and won a legal monopoly from New York State on the lucrative Hudson River trade. Aaron Ogden, who owned a steam engine plant in Elizabethtown, emerged as a determined competitor. He fought the Fulton monopoly for several years, then paid dearly to acquire a share of it in 1815.

Just when matters should have grown easier for Ogden, trouble arose with Thomas Gibbons, an abrasive lawyer and businessman. First, Ogden had Gibbons arrested to collect a debt. Ogden apologized, claiming the arrest resulted from misunderstandings. But when Gibbons’ wife, Ann, sought advice about divorcing her husband, he provided it.

Gibbons sought leverage through Ogden’s oldest friends. He had secretly purchased from Dayton, who was struggling financially, an interest in Ogden’s ferry business. He dispatched Dayton to persuade Ogden to drop Ann Gibbons’ cause. Gibbons then turned to Burr, who was trying to revive his law practice in New York. Burr advised a court attack on Ogden’s monopoly. Gibbons filed the case.

That lawsuit lasted for years, long after Ogden lost his steamboat business to his bank. Marshall’s opinion in Gibbons v. Ogden, delivered in 1824, struck down Ogden’s monopoly, ruling that states cannot limit interstate commerce under the Constitution.

But the Jersey Boys’ friendship survived even that. In that same year, Ogden and Dayton jointly hosted an old comrade, the Marquis de Lafayette. Dayton, 64, died a few weeks later.

When Ogden’s debts landed him in a New York prison, Burr rode to the rescue. He won enactment of a state law providing that no veteran of the Revolutionary War could be jailed for debt. Ogden was released.

In the 1830s, the two Aarons resided for a brief time as neighbors in Jersey City, and each lived past 80. (Burr died in 1836, Odgen in 1839.) Their long histories reflected the adventure of the infant America, where opportunity and disaster lay side by side, where everything seemed possible to those who were–like the original Jersey Boys–bold, talented and not too fussy about what other people thought.

David O. Stewart’s new book, American Emperor: Aaron Burr’s Challenge to Jefferson’s America, explores Burr’s western expedition, the most audacious scheme of the leader of the Original Jersey Boys. His previous books are The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution, and Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy.