Cache of 19th-Century Blue Jeans Discovered in Abandoned Arizona Mineshaft

The seven pairs of pants open a portal into life in the Castle Dome mining district

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/aa/d1/aad156b4-ab1b-41f3-9bb2-5219c359a431/jeans.jpg)

When Nevada-based tailor Jacob Davis received an order for a hardy pair of work pants in December 1870, he decided to experiment with a new design, reinforcing the seams and pockets of canvas trousers with copper rivets. A Latvian-born immigrant living in Reno, Davis soon partnered with Levi Strauss, the dry goods merchant who’d provided the canvas cloth, to launch his product on a large scale. The pair filed a patent in May 1873, with Davis noting that his method “avoid[ed] a large amount of trouble in mending portions of seams which are subjected to constant strain.”

Now known as blue jeans, the modern descendants of Davis’ invention evoke the gritty era of standing in a river to pan for gold or entering a mineshaft to pick away at rock. But while denim is ubiquitous today, surviving examples of 19th-century jeans are few and far between. In 2018, an 1893 pair of Levi’s set the record for the world’s most expensive pair of jeans, selling at auction for nearly $100,000; earlier this month, a pair of 1880s Levi’s discovered in an abandoned mineshaft fetched $87,400 (including buyer’s premium).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f7/a8/f7a8bf2b-0b1f-4f99-a175-53b15f05745e/pants.jpg)

The relative rarity of historic denim makes a discovery by YouTuber Frank Schlichting even more significant. Early in 2020, Schlichting found seven pairs of 1800s jeans in an abandoned mineshaft in Yuma, Arizona. The cache included two pairs each from Levi Strauss & Co., Stronghold and Pacific Coast, and one pair from Triumph. (The latter two brands are now defunct.)

Allen Armstrong, CEO and founder of the Castle Dome museum, mine and ghost town where Schlichting made his find, had previously explored the same shaft but missed the trove of jeans, coming within 20 feet of it. He did, however, find a pair of Levi’s 201s—a lower-priced version of the classic 501s, created around 1890 with cheaper buttons and a linen label rather than leather—on his first rappel to the shaft two decades ago.

To authenticate the Levi’s, Armstrong turned to Levi Strauss & Co. historian Tracey Panek, who drove out from California. “She carried [the jeans] around for two hours like they were a little kid in her arms,” says Armstrong.

Based on details of the denim’s design, including a single back pocket (the company only added a second back pocket to its pants in 1901), Panek deemed the jeans genuine 19th-century Levi’s. “A one-time finding of seven pairs of denim pants, including the riveted Levi’s 201 waist overalls, is phenomenal,” she says.

Unearthing the long-lost jeans

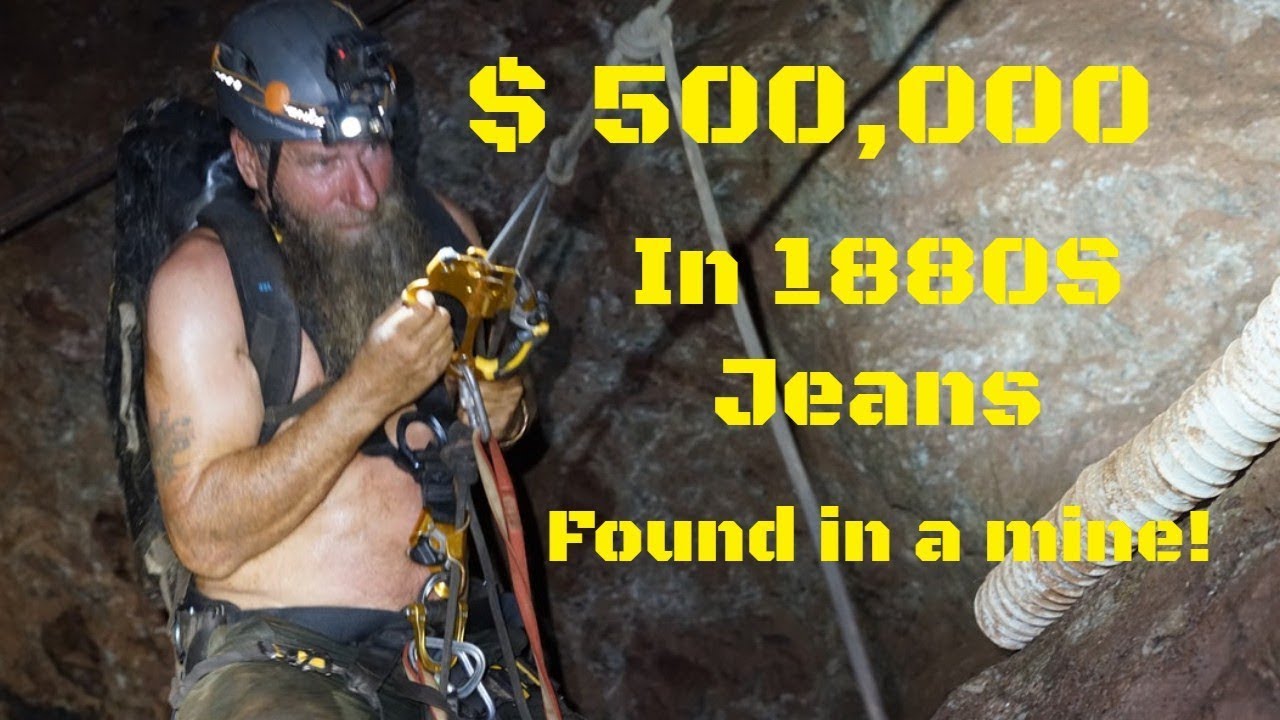

Schlichting’s YouTube video, which has garnered more than 1.5 million views since February 2020, begins with his colleague Gabe Romo descending into the 250-foot mineshaft, as captured by a GoPro helmet camera. Upon reaching the bottom of the shaft, Romo removes his harness and climbs a short ladder to a sublevel where Schlichting awaits. Using a pickax and their hands to shift through rubble, the explorers—who didn’t set out in search of denim specifically—pull pair after pair of jeans from the dirt.

Armstrong gave Schlichting and Romo permission to survey the mineshaft with the understanding that anything they found would end up in the nonprofit Castle Dome museum. Securing consent from the owners of mineshafts is key to this kind of exploration, as trespassing in seemingly abandoned mines can result in criminal charges. On top of the legal fallout, exploring such spaces carries “a great magnitude of danger,” posing hazards like cave-ins, flooding and falling rocks, according to Armstrong.

Schlichting mentions other risk factors, too, like hibernating rattlesnakes, cellphone lights and flashlights dying, and poor-quality air in coal mines. Each person on his team carries $1,500 worth of equipment, from harnesses to oxygen monitors to auto-stop equipment that automatically ends a descent in the event of trouble. “We haven’t had a major issue or rescue, but we’re pretty cautious,” he says. “We have the best lighting and equipment to do this.”

Resurfacing toward the end of the Castle Dome footage, Schlichting and Romo present their finds to Armstrong. The jeans are gray with filth and dotted with wax from candles, which would’ve been attached to bands around the 19th-century miners’ heads. Dust flies off the pants every time Armstrong touches them.

Denim and Castle Dome

Despite the decades of grime, the jeans are remarkably well preserved, in large part thanks to the Arizona desert’s aridity. How the denim ended up in the mine in the first place, however, remains a mystery. As Schlichting speculates, “The most logical explanation [is the miners] found a major discovery, and the mine owners gave them new jeans” as a reward. Outfitted in new attire, the miners may have discarded their old denim in the spot where they ate lunch or kept their tools. Alternatively, the men may have left their dirty clothes in the mine and ascended to the surface in clean gear, failing to return to the site and recover their used jeans for reasons unknown. A third explanation is the jeans belonged to the mine, which provided them to miners as a work uniform.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/43/de/43de0366-f383-4806-b524-7ab55333f400/img640.jpg)

The shaft in question is one of roughly 300 mines in the Castle Dome mining district. Prospectors arrived in the area in the early 1860s, discovering ore veins previously worked by Native Americans. Over the next two decades, the mining town of Castle Dome Landing grew in size and stature, attracting 50 residents, a post office, a general store, a hotel and a saloon, according to the 1969 book Ghost Towns of Arizona.

By the early 1880s, miners had exhausted the site’s ore, and the bustling compound began to decline. Castle Dome enjoyed a brief resurgence during the first half of the 20th century, supplying lead for military projects during both world wars. But the renewal was short-lived, and all of the area’s mines had closed by 1978. Today, the Imperial Dam reservoir covers any surviving traces of Castle Dome Landing; Armstrong’s mine, museum and ghost town—opened to the public in a different section of the district in 1998—preserve Castle Dome’s colorful history.

The history of blue jeans

In the modern imagination, the name Levi Strauss is synonymous with blue jeans. But Strauss didn’t begin his career as a fashion maven. Instead, the German immigrant founded Levi Strauss & Co. as a San Francisco-based dry goods wholesaler in 1853. The company had a contract with prisons in California and Arizona to provide fabric for bedding and striped cloth for inmates’ uniforms, among other business ventures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/f1/c7f1c999-5930-4451-92da-b71c37600ae9/levi.jpg)

“Levi’s jeans are an iconic piece of American history,” says filmmaker Jackie Krentzman. “But what isn’t as well known is the fact that Levi Strauss was part of a cadre of Jews from Bavaria who came to San Francisco during the Gold Rush to escape persecution and seek their fortune.” Krentzman’s 2013 documentary, American Jerusalem: Jews and the Making of San Francisco, includes footage of Strauss’ childhood home in Buttenheim, Germany, which is now a museum.

As Krentzman explains, Strauss and his fellow immigrants sold goods to miners but typically didn’t work in the mines themselves. Back home in Germany, she adds, some Jews worked as peddlers “because they were barred from many professions in mid-19th-century Bavaria.” Selling wares then “turned out to be the job most needed during the Gold Rush.”

Levi Strauss & Co.’s signature blue jeans were the brainchild of tailor Davis, who brought Strauss on board to manage the business side of things in 1873. “A lady said, ‘My husband rips every pair,’ so [Davis] riveted canvas for her,” notes Brit Eaton, the denim collector who placed the $87,400 pair of jeans up for auction earlier this month.

Headed by Strauss with everyday production overseen by Davis, the company quickly won accolades for its sturdy work pants. Much of its success stemmed from its signature copper rivets, which fortified the cloth at its most stress-prone areas and lent color and recognizability to the Levi’s brand. “Strauss … didn’t make just the jeans, but this was the principal thing he was making, and they were very popular,” Nancy Davis, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, told Smithsonian magazine in 2011.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/18/05/18055bbb-8107-4142-a097-e1d82194b135/britlevidetail.jpg)

One pair of Levi’s found by Schlichting features an early company logo: two horses pulling a pair of jeans in different directions, unable to rip the pants apart. Introduced in 1886, the design was created for easy identification. “Some people wearing our products would’ve been immigrants and may not have been able to read English, so at least they could recognize the image, which demonstrates strength,” says Panek.

A separate label sewn on the inside pocket of certain late 19th-century Levi’s jeans speaks to the darker side of the mining boom, which brought an influx of immigrants—Strauss and Davis included—to the American West. Both a pair of Levi’s from Castle Dome and the pants sold by Eaton bear the phrase “the only kind made by white labor.” Part of a broader wave of anti-Chinese sentiment sparked by the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the racist slogan only appeared on Levi’s merchandise for a brief period. As a spokesperson tells the Wall Street Journal, the company dropped the phrase in the 1890s.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0a/12/0a12525e-464e-459b-b175-0746309e6445/img292_copy.jpg)

Around that same time, in 1890, Davis and Strauss’ copper riveting patent expired, allowing competitors to surge onto the market with their own denim pants. Some of these businesses copied the Levi’s two horses logo, simply swapping in animals like elephants and dogs.

Despite stiff competition, Levi’s managed to retain customers’ loyalty. The company—and its flagship product—evolved, attracting buyers from all walks of life and becoming an everyday fashion staple. To quote the popular idiom, blue jeans are as American as apple pie.

The value of historic denim

In August 2021, the Castle Dome jeans went on view at Armstrong’s nonprofit organization in Yuma. Initially so dirty their brands were misidentified in the YouTube footage, the pants have since been hosed off. They’re not the rich blue associated with denim today, but the various patches and buttons that helped Panek identify them are now visible. And though Armstrong has no intention of selling the jeans, that hasn’t stopped interested parties from speculating on their value.

“Theoretically, we found $300,000 worth of denim,” says Schlichting. “Those jeans are worth more than their weight in gold.” The explorer’s days of adventuring in mines aren’t over; last year, he and his wife purchased a historic mine in Grand Forks, Canada. They’re now working to restore it to its former glory.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f7/bd/f7bdd335-98a8-4db7-9e50-3e743358d057/screenshot_20200207-202027_facebook.jpg)

Panek says the jeans are “priceless to us, of course. I would love to have them in [Levi Strauss & Co.’s] collection, but it makes sense to keep them where they were found.” Pressed to name a figure, she adds, “They can range in the tens of thousands. I usually refer to an auction house.” (Back in 2001, Panek’s Levi’s predecessor paid an eBay seller $46,000 for a late 1800s pair now housed in the company’s San Francisco archives.)

“Everything in this collector world is an inflated value, what’s popular at a certain time,” says Eaton. Though the Stronghold, Pacific Coast and Triumph jeans are rarer than the Levi’s, “Levi’s are what people collect,” he adds. “Because [the non-Levi’s are] scarce, they’re interesting to me as a collector. But I appreciate Levi’s, too.”

Armstrong, for his part, says, “I don’t care what they’re worth. It’s the history that’s valuable, the great heritage of this country. … People want denim because they think they’re going to get rich off them, but I’m greedy for the history.”