Why Americans Flocked to Catch a Glimpse of Hitler’s Car

At carnivals and state fairs across the country, curious onlookers were drawn to the Fuhrer’s chariot

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/1c/a81c49d5-b05a-4c81-8f71-301a7a8b9db3/gottfried-feder.jpg)

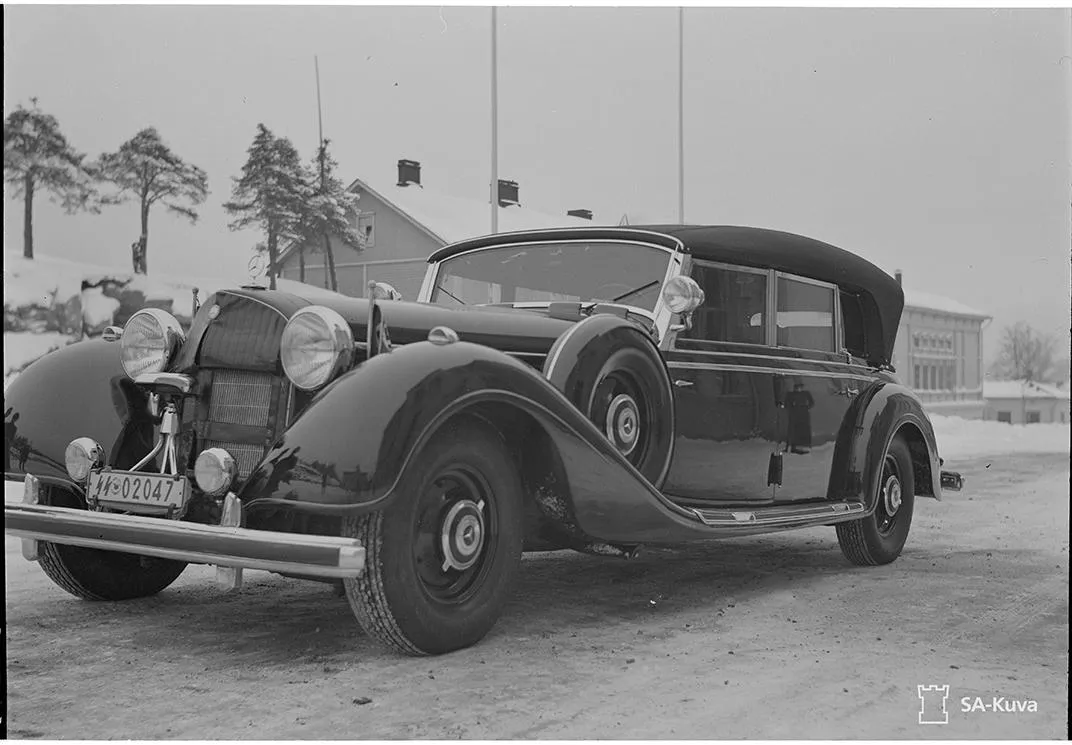

When Chicago businessman Christopher Janus bought a used Mercedes-Benz from a Swedish firm in 1948, he had to deal with more than just the car’s mammoth size (it was seven feet wide and weighed five tons) and abysmal gas mileage (four to seven miles per gallon). Janus was also forced to grapple with the car’s ghosts. The behemoth was formerly owned by Adolf Hitler—or so Janus thought.

In his new book The Devil’s Mercedes: The Bizarre and Disturbing Adventures of Hitler’s Limousine in America, Robert Klara takes readers across the country with two Mercedes-Benz limousines whose ties to the Nazis made the cars irresistible attractions at state fairs and exhibition halls. One car was a war prize of American GI Joe Azara. The other was part of an import deal. Both were equipped with over a dozen secret compartments, a folding passenger-side platform on which Adolf Hitler could stand to add six inches to his 5-foot-8 height, and a 52-gallon gas tank. They also both toured the country, drawing crowds and earning money for charities and the U.S. military. But which one actually belonged to Hitler?

To unravel the mystery and understand their powerful symbolism, Klara dove into the history of both cars’ origins. But the real discovery wasn’t deducing whether or not they were driven by Hitler; it was uncovering the profound effect the cars had on American audiences. Smithsonian.com talked to Klara about his inspiration for the book, what the cars symbolized in the post-war period, and how they helped Americans grapple with the violence wrought by the Nazis.

What inspired you to tackle this subject?

I had wanted to do a story about the cursed object. Strangely enough, you could even say this idea started at the Smithsonian, because I’d been in Washington a number of years ago and devoted a few days just to museum hopping and made a point of seeing the Hope Diamond, which is surrounded by a great deal of lore. I’m not sure how credible those stories are, but some of the people who owned it met with early and unpleasant ends. That idea was rolling around my head and I thought, what about a cursed car? That would be pretty unusual. I started cycling through those and I went through the predictable ones, the car that Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in and none of those seemed to pan out. Then out of the blue I thought, what did Hitler drive around in? That was the beginning point of this.

I think in a sense just about anything associated with Hitler can be cursed in a metaphorical way. There’s such an aura and symbolic weight to anything associated with that man. I wasn’t looking to do something sensational about him, and I wasn’t looking to add just another Hitler book to the pile of ones that are out there, but nobody had really tapped into this before. There’s something specific about an automobile, especially in the American psyche. Cars have never been just means of transportation for us. They’re windows to people’s personalities and so I thought, there’s a great deal to work with here. It just started rolling, as it were, and getting stranger by the month.

Did you realize there was a mystery behind the true car that belonged to Hitler?

No, I completely lucked into that to be honest. But when I started digging through old newspaper accounts, I kept seeing mentions of Hitler’s car and at some point had a whole stack of old newspaper stories and it became clear to me that there’s no way it could’ve been just one car. I thought, don’t even tell me there was more than one of these crazy things here, and of course there were.

It wasn’t important to me to do a definitive guide to Hitler’s automobiles. I wanted to tell a story that was set in post-war America about these objects as they influenced Americans’ understanding of World War II, both as a military event and as something with a great deal of moral and historical weight. I wasn’t really interested in chasing every single car through the midways of America.

How did people respond to seeing Hitler’s cars?

It was a whole range of responses. What was more surprising to me was the intensity of those responses, which ranged from extreme and perhaps unhealthy fascination on through to anger to the point of violence. I’m hard-pressed to think of many other objects that would have that effect on the public.

Obviously there was so much more going on than the exhibition or sale or display of an old Mercedes-Benz. Even if this was a one-of-a-kind car, which it wasn’t, you wouldn’t have tens of thousands of people waiting in line to look at a Mercedes-Benz. I think what was happening is when they were looking at Hitler’s car, in a sense they were looking at Hitler. These cars have always been a proxy to Hitler. In the immediate post-war period, the late ’40s and early ’50s, this car was a tangible, visceral link to the biggest war in our history. It allowed visitors to face, if only by proxy, if only symbolically, the man who was responsible for burning a great portion of the world.

Do you think the cars gave Americans a better understanding of the war?

There are many parts of the American public, then and now, who are not inclined to visit museums or do a great deal of reading about historical subjects. And I don’t argue that the car enabled people to learn very much about the Second World War, but it certainly, in the minds of a lot of people, put them in touch with it. As to what they got out of it—it’s hard to say. Did they come away with a deeper understanding of the war? It’s doubtful to me. Insofar as they promoted awareness of the war, the cars furnished people with a means of coming to terms with it, if that’s not giving too much credit to an old Mercedes-Benz. Perhaps it didn’t enrich people very much, but it provoked thought and reflection.

It’s something on the order of 10 percent of Americans were actually involved in the fighting in the two major theaters of the war, and that is an enormous number of people, but it leaves about 90 percent of the country on the home front. Their picture of the war would’ve been limited to newsreels that they saw in theaters and to newspaper and radio stories. Many of those were sanitized to one degree or another and given a steep patriotic slant. One of the arguments I advance in the book is when an artifact that is not only this large and unusual, but one that is linked or believed to be linked to Hitler himself came back to the U.S., it represented a very rare and unusual opportunity for people to interact with an artifact from the war. That was something that just was not easy to do. I think the uniqueness of this car’s presence on American soil went beyond the spectacle of it and into the realm of it being a kind of tangible symbol.

Why are cars so symbolically important to Americans?

Our primary means of getting around has been the automobile ever since the interstates were built after the war and we let what had been the world’s finest railroad system collapse. There’s always been something of the American identity interwoven with the fabric of the automobile that you just don’t see in other places. The car has always functioned for Americans as a symbol of what you’ve been able to attain in the world. It’s a badge of pride sitting in your driveway, so the brand is important and the make is important, and especially in my Brooklyn neighborhood how relentlessly you can trick out the car is important. The car is an integral part of our identities as Americans and I think that fact played very heavily into the public’s fascination with these cars.

But also, the Mercedes-Benz Grosser 770K played a functional part in the propagandist structure of National Socialism. It was designed to be a very strong, powerful, over-large intimidating machine. It was part of the Nazi stagecraft. So the kind of awe and fear and intimidation that the car inspired in Germany, it was something that you could still experience by looking at it here.

Does putting the car up for display, especially at fairs, trivialize the horror of the war? Should we just have destroyed the cars?

There’s no doubt an element of distaste in all of this. Especially given the fact that many of the settings in which the car was displayed were essentially midways and sideshows. There were many people who wanted to [junk the cars]. There was one gentleman who bid on it at an auction who publicly pledged to destroy it. Personally, I don’t believe that we are better off destroying any artifact simply by virtue of its association, even with something as horrible and tragic as World War II. Every relic, every artifact, can be deployed for as much good as bad and the responsibility rests with the owner to put this object in context.

The two cars that are in this book, one is with a private owner and the other is in a museum, so the sideshow days are past. One of the ways we understand and interpret the cultural past is to lay eyes upon these objects, which in and of themselves are rarely much to look at. But if it’s put in proper context, an academic or museum setting, displayed in such a way that you understand where it came from and what it means, physical artifacts can go a great way in making sense of the world.

What do you hope readers get out of the book?

More than anything, I hope that the book demonstrates the way our understanding of an event like World War II has evolved and grown more sophisticated over the decades. When the two cars were first put on display, it was in a very rah-rah, patriotic, “yay-us” fashion. And now if you take a look at how the Canadian War museum car is displayed, it is so much more sobering. The car is arguably more frightening than ever, as it should be. In the immediate days after the war, everybody I think was grateful that it was in the rearview mirror, if you’ll forgive the automotive pun, so the car was little more than war booty and a way to sell bonds. It evolved over the years, through a lot of somewhat tawdry and somewhat distasteful steps, to the point where today, the car is instrumental in helping people to understand the magnitude of the tragedy that that war was.

The other thing that I hope people take from it is a greater understanding of the power of symbols and how they can be deployed for both good and evil. One of the things that pleased me about how these cars were used, many of the owners of this car put them on display—granted in environments that were very lowbrow—but donated the proceeds to charities. And I thought that that reversal of polarity was fascinating. Because their intent, whether they succeeded or not, was to take something that had been a symbol of great evil and turn it on its head into an engine for doing some good. To me that demonstrated the central role that symbols play in the culture.

We’re really just talking about a Mercedes-Benz here at the end of the day. The effect the car had on people derived from the symbolic weight the car carried. The fact that as time went on that the car could actually be used to do some good, either giving money through charity or today in a museum setting demonstrates to me that even something as horrifying as an automobile that drove Hitler through the Nuremberg rallies can now be a means of understanding what happens when a megalomaniac gains control.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)