How an Obscure Photographer Saved Yosemite

The beauty of the national park became clear long before Ansel Adams

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dc/a5/dca52bfd-5dd8-40b5-ab25-a2c7a311bce1/jun2016_e03_phenom-wr-v1.jpg)

In June of 1864, as Sherman’s armies were moving toward Atlanta and Grant’s were recovering from a bloody loss at Cold Harbor, President Abraham Lincoln took a break from the grim, all-consuming war to sign a law protecting a slice of land “in the granite peak of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.” The act granted the area “known as the Yo-Semite Valley” to the state of California, to “be held for public use, resort, and recreation...inalienable for all time.” It was the federal government’s first act to preserve a part of nature for the common good—a precursor of the National Park Service, now enjoying its centennial—and it might not have happened but for an obscure 34-year-old named Carleton Watkins.

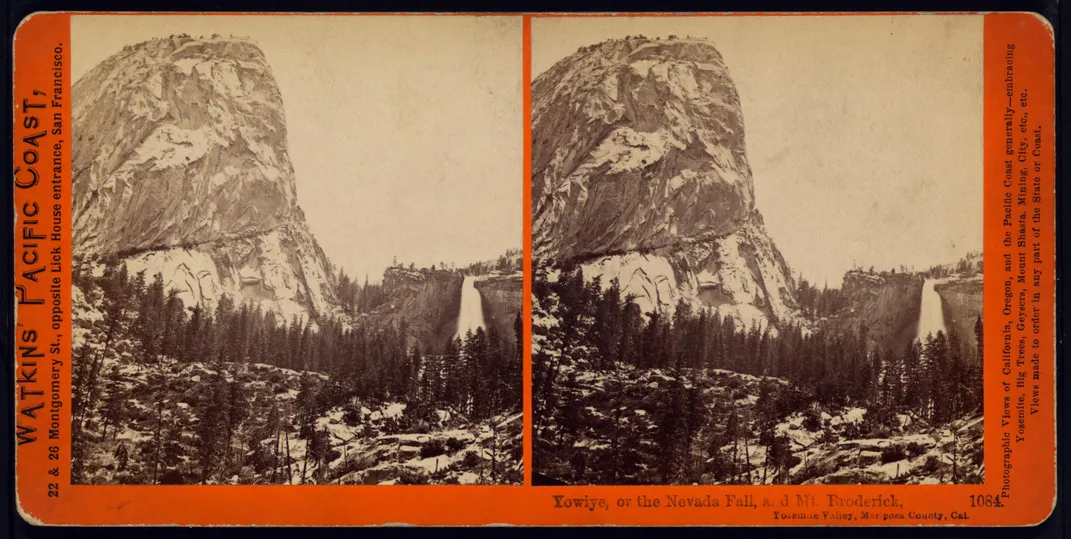

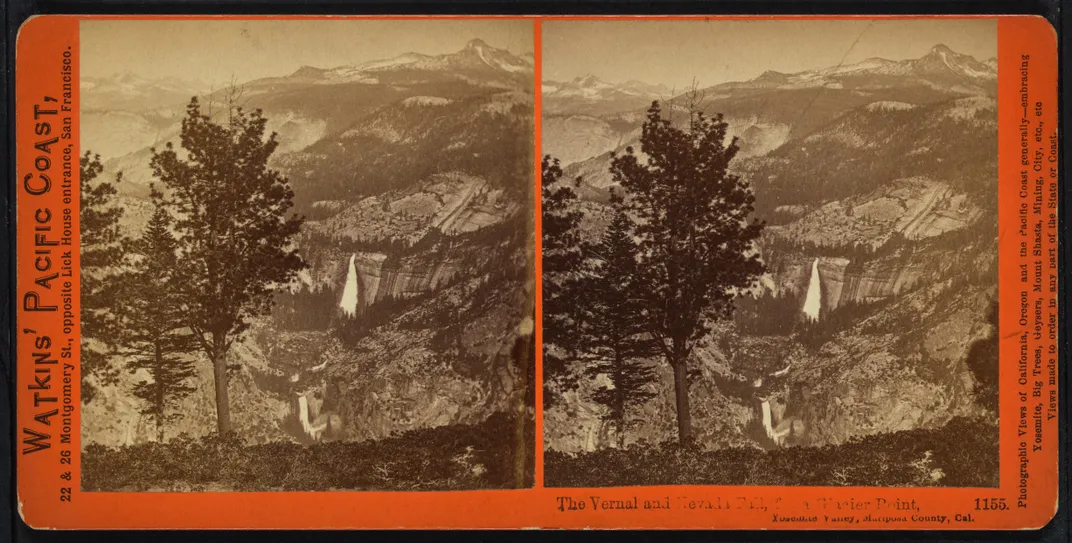

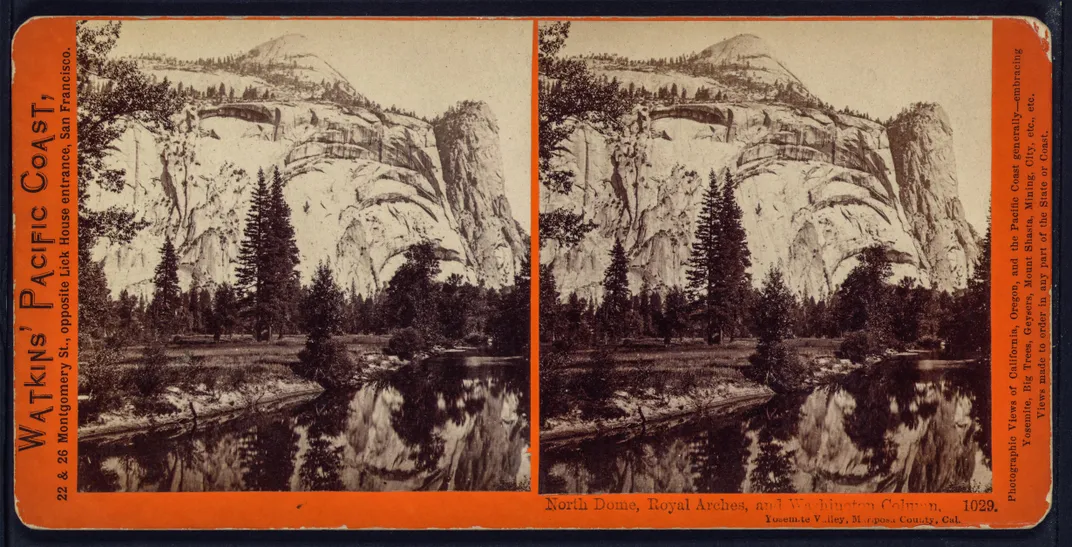

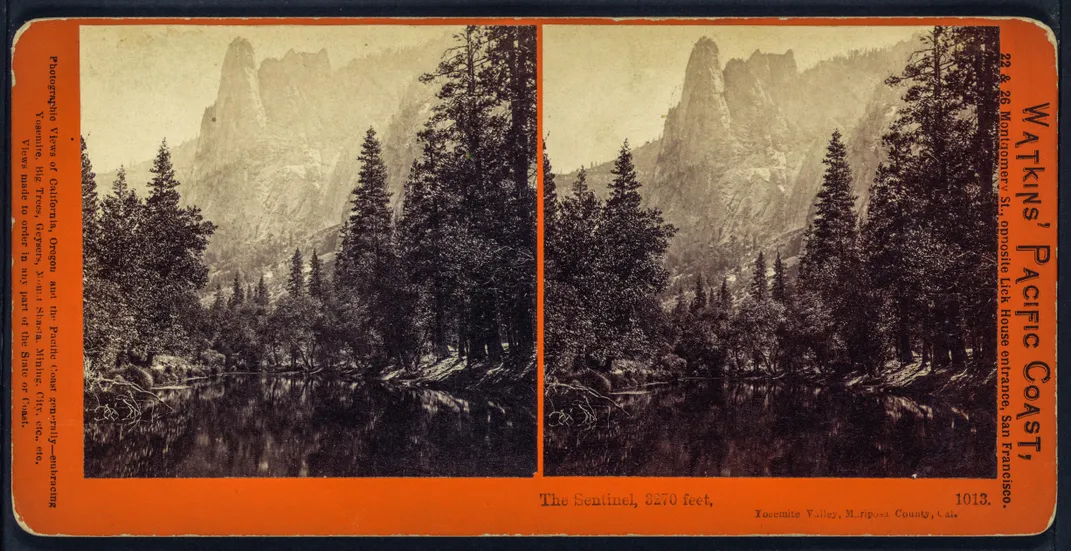

Born in a small town in New York, Watkins headed west in 1849 to seek his fortune in California’s gold rush, to no avail. After apprenticing to a pioneer daguerreotypist named Robert Vance, he made his money shooting mining estates. In the summer of 1861, Watkins set out to photograph Yosemite, carrying a literal ton of equipment on mules—tripods, dark tent, lenses and a novel invention for taking sharp photographs of landscapes on glass plates nearly two feet across.

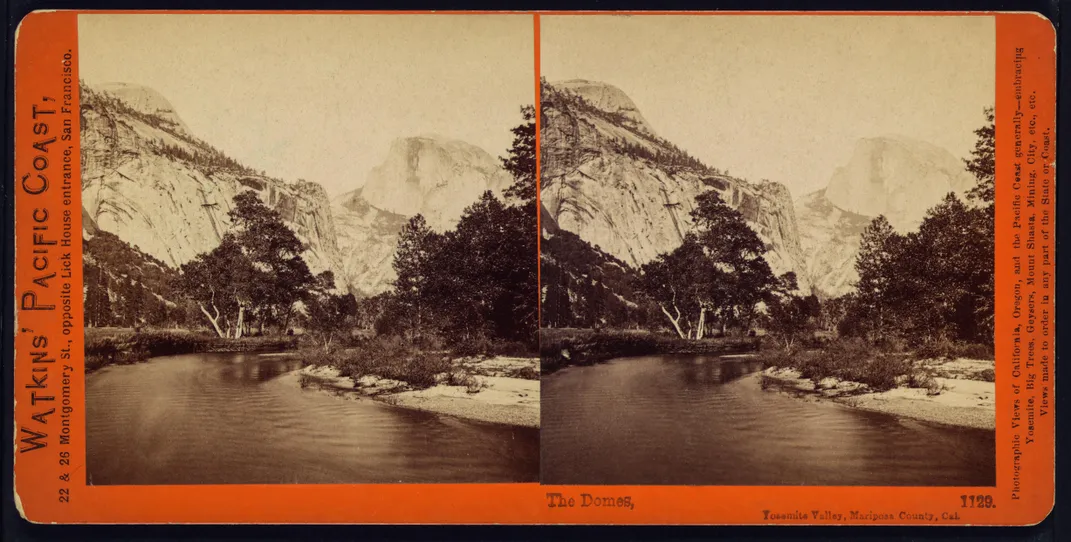

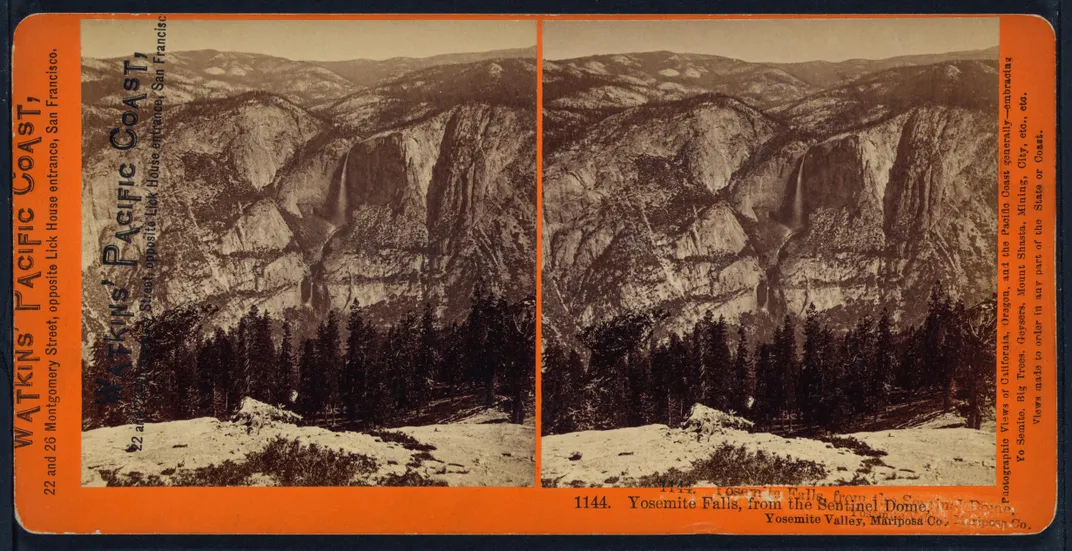

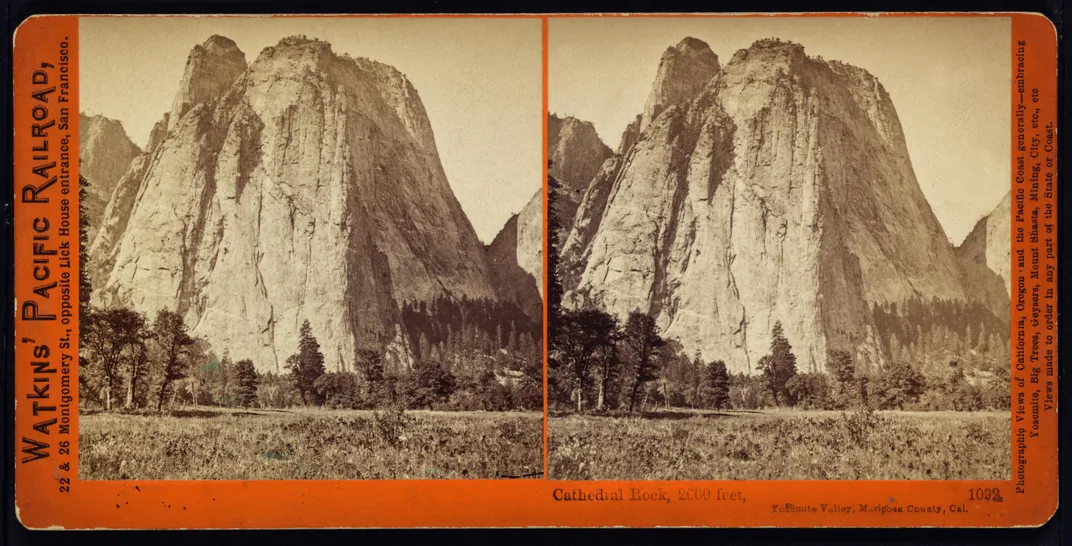

We associate Yosemite with the photographs of Ansel Adams, who acknowledged Watkins as one of “the great Western photographers,” but it was Watkins who first turned Half Dome, Cathedral Rocks and El Capitan into unforgettable sights. Weston Naef, a photography curator and co-author of a book about Watkins, described him as “probably the greatest American artist of his era, and hardly anyone has heard of him.”

Sketches and awed descriptions of Yosemite’s grand views had reached the East in the mid-1800s, but nothing provoked public reaction like Watkins’ photos, which were exhibited at a gallery in New York in 1862. “The views of lofty mountains, of gigantic trees, of falls of water...are indescribably unique and beautiful,” the Times reported. The great landscape painter Albert Bierstadt promptly headed to Yosemite. Ralph Waldo Emerson said Watkins’ images of sequoias “are proud curiosities here to all eyes.”

Watkins’ works coincided with a move by California boosters to promote the state by setting aside lands in Yosemite, home to “perhaps some of the greatest wonders of the world,” Senator John Conness bragged to Congress in 1864. Historians believe that Conness, who owned a collection of Watkins photographs and was a friend of Lincoln’s, showed the images to the president the year before he signed the bill protecting Yosemite.

Watkins’ fame as a photographer rose, and he journeyed throughout the West: Columbia Gorge, the Farallones, Yellowstone. But he kept returning to Yosemite. Today, it can be hard for us postmodernists, who are more used to images of wilderness than the thing itself, and who tend to associate photographs of Yosemite with clothing ads, to imagine the impact of those first vivid pictures. Yet somehow they retain their power—make us “look anew at nature itself, shining with a clarity that is at once ordinary and yet very magical,” says Christine Hult-Lewis, a Watkins expert.

In his later years, Watkins lost his eyesight, and then his livelihood. The 1906 earthquake destroyed his studio and many of his negatives (and threw 4-year-old Ansel Adams against a wall, giving him a crooked nose). For a time Watkins lived with his wife and children in a boxcar. He died 100 years ago this month, 86 years old, broke and blind, at Napa State Hospital, an asylum. Two months later, President Woodrow Wilson established the National Park Service, a steward for the sublime place Watkins had shown to a war-weary nation.

Carleton Watkins in Yosemite