Carving Out the West at the Great Smoke Conference

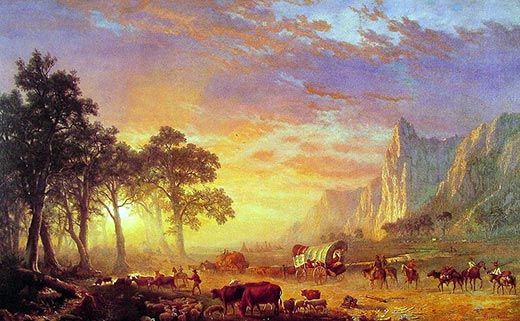

In 1851, American Indian tribes gathered to seek protection of their western lands from frontiersman on the Oregon Trail

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Albert-Bierstadt-Oregon-Trail-631.jpg)

In 1851, the United States Congress invited the widely scattered Indian tribes of the West to gather for a grand peace council at Fort Laramie in the Nebraska Territory. Conceived and organized by treaty commissioners Thomas Fitzpatrick, the Irish immigrant who blazed open the Oregon Trail in 1836, and David Mitchell, the Indian superintendent for the West, the Indians called the gathering "The Great Smoke." For its part, Congress wanted safe passage for white settlers on the Oregon Trail. For theirs, Indians wanted formal recognition of their homelands—1.1 million square miles of the American West—and guarantees that the United States Government would protect their lands from encroachment by whites. In a month-long spectacle of feasting and negotiating on a scale that would never be repeated, they both got their wish.

The celebrations that marked the end of the peace council at Horse Creek, the drumming and dancing, singing and feasting, went on without pause for two days and nights. On the evening of September 20, the treaty commissioners’ long-awaited supply-train appeared on the eastern horizon, prompting a great rejoicing in the Indian camps arrayed among the hills above the North Platte. The following day, commissioner David Mitchell rose early and raised the American flag over the treaty arbor. One final time he discharged the cannon to call Cat Nose, Terra Blue, Four Bears, and all the other headmen, to the council circle beneath the arbor. There, where Dragoons had worked into the wee hours of the morning unloading the wagons bearing gifts and provisions, the Indians quietly gathered at their accustomed places. Dressed in the gayest of costumes and painted with glaring hues of their cherished vermillion, Mitchell presented the chiefs with gilt swords and the uniforms of generals. Then, he called each band forward to claim its gifts, and despite the atmosphere of great excitement, the vast multitude of Indians remained calm and respectful, and not the slightest trace of impatience or jealousy was apparent throughout the ceremony.

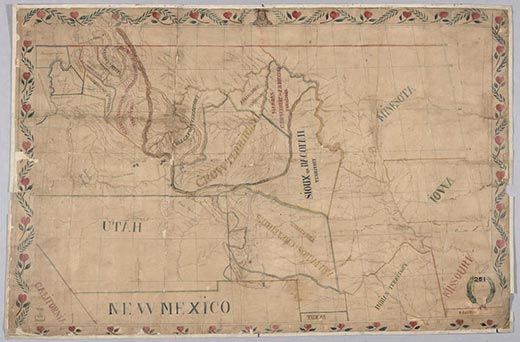

For weeks, 15,000 nomads of the great western tribes had set aside their ancient animosities and camped together in a spirit of peace and friendship at the confluence of the North Platte and Horse Creek in the Nebraska Territory. The legendary mountain man Jim Bridger, Jesuit priest Pierre De Smet, and Thomas Fitzpatrick, the intrepid adventurer and trader, met each day with the headmen of the twelve tribes to etch the first boundaries into America’s vast western landscape, a region marked on maps of the day as “territory unknown.” It was a deliberate, painstaking process, and day by day, one river, one mountain range and one valley at a time, a new American West gradually took shape on a map that was unlike any previously drawn. Bridger and De Smet found themselves embroiled in a world of geographical nuance and arcane oral histories, all of which had to be squared, as neatly as possible, on a sheet of parchment showing dozens of geographic features that were known to fewer than half a dozen white men.

When the task was completed, political boundaries establishing a dozen new tribal homelands covered a contiguous swath of real estate larger than the entire Louisiana Purchase. The 1.1 million square miles of land claimed by the western tribes in the treaty negotiated at Horse Creek (and ratified the following year by the U.S. Senate) would one day envelop twelve western states and corral the future cities of Denver and Fort Collins, Kansas City, Billings, Cheyenne and Sheridan, Cody and Bismarck, Salt Lake City, Omaha and Lincoln, Sioux Falls and Des Moines, within one vast territory that was owned, as it had been since time immemorial, by Indian nations.

By month’s end, the Indians’ vast herd of 50,000 ponies had nibbled the last blade of short grass to dust and roots, for miles around. The slightest evening zephyr raised a choking wall of flying refuse and human waste that engulfed the sprawling encampment in swirling clouds of debris. So once the tribal headmen had touched the pen to the final document, and once the presents had been distributed by Mitchell at the arbor, the women quickly struck the teepees, loaded the prairie buggies with their belongings, and gathered up their children for the long journey home.

With quiet elation, Thomas Fitzpatrick, the white-headed Irishman and long-time friend the Indians called Broken Hand, watched from the solitude of his camp as the last bands of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho struck their villages. Despite his ambivalence about the Indians’ future, Fitzpatrick had worked diligently for many years to persuade the western tribes to meet in a formal peace council with the Great White Fathers. Certainly, no one’s diplomatic skill or intimate knowledge of the tribes–their many languages, unique customs, and of the country they occupied–had been more instrumental in bringing the council to a successful conclusion. Old men such as Cat Nose and Gray Prairie Eagle knew that this was the first gathering of its kind in the history of the American West, and that most likely it would be the last. Events of coming years would affirm their clairvoyance, as no assemblage equal to its grandeur and its diplomatic promise would ever again be convened on the high plains of North America.

For the moment, however, such reflections were luxuries to be enjoyed by white men in distant towns, villages, and cities, men whose proxies had at long last claimed their coveted prize–safe passage for white settlers through Indian country to the Oregon Territory and the new state of California. The road to Canaan by way of Manifest Destiny, unburdened of legal encumbrances and threats of hostility from the tribes of the plains, was now open to the restless multitudes. For the Indians the true test of the Great White Father’s solemn promises lay not in words and lines drawn on a sheet of parchment, nor in the ashes of the council fire, but in deeds done on an unmarked day in an unknowable future. In one fashion or another, the old men knew that test would come just as surely as the snows would soon fly over the short grass prairie.

As they were bundling up their lodges and preparing to leave, Cheyenne hunters rode back to camp with stirring news. A large herd of buffalo had been sighted in the country of the South Platte, two days’ travel to the southeast. Waves of excitement raced through the villages. The Cheyenne and Sioux, with their enormous encampments, were particularly eager to make one last chase before the first snows drove them into their winter villages at Belle Fourche and Sand Creek. From their separate camps, Fitzpatrick, Mitchell, and De Smet, watched the last members of Terra Blue’s band ride away in the late afternoon. Before long, after leaving behind swirling motes of dust on a grassless plain, the nomads merged with the southern horizon. The broad and familiar sweep of the North Platte country was suddenly forlorn and strangely hushed. It was as if the grand kaleidoscopic pageant of the gathering–an event unique in the pages of America’s rapidly unfolding story–had been nothing more than a colorful prelude to a feast of bones for the coyotes, raptors, and the implacable wolves.

(Excerpted from Savages and Scoundrels: The Untold Story of America’s Road to Empire through Indian Territory by Paul VanDevelder, published by Yale University Press in April 2009. Copyright 2009 by Paul VanDevelder. Excerpted by permission of Yale University Press.)