On a Saturday afternoon in February 1933, at the Fort Apache Reservation in Arizona, a White Mountain Apache Indian named Silas John Edwards and his wife, Margaret, stopped by a friend’s place to visit and relax. Edwards, a trim middle-aged man with a penetrating gaze, was an influential figure on reservations throughout the Southwest. Hundreds of followers regarded him as a divinely inspired religious leader, a renowned shaman and medicine man.

When he and Margaret arrived at their friend’s dwelling, a tepee, they found people drinking tulapai, a homemade Apache liquor. Three hours later, the Edwardses joined a group heading to another friend’s home. People who were there reported that Margaret confronted him inside a tepee, demanding to know why he’d been spending time with a younger woman, one of Margaret’s relatives. The argument escalated, and Margaret threatened to end their marriage. She left the party. Edwards stayed until about 10:30 p.m. and then spent the night at a friend’s.

Shocking news came the next day: Margaret was dead. Children had discovered her body, along with bloody rocks, at the side of a trail two and a half miles outside of the Fort Apache town of Whiteriver. They alerted adults, who carried her body home. “I went in the tepee and found my wife in my own bed,” Edwards later wrote. “I went to her bedside and before I fully realized what I was doing or that she was really dead, I had picked her up in my arms, her head was very bloody and a part of the blood got on my hands and clothing.”

He was still kneeling there, holding his wife’s body, when a sheriff and an Apache police officer arrived. The reservation was patrolled largely by Indian officers, but ever since the Major Crimes Act of 1885, certain crimes on Indian reservations had fallen under federal jurisdiction. Murder was one of them.

A medical examiner reported that Margaret had been killed by blows to her head and strangulation. Curiously, at least two of the rocks used to crush her skull were inscribed with her husband’s initials: S.J.E.

The rocks were key pieces of evidence when Edwards stood trial in federal court in October of that year. The 12 white men on the jury delivered a guilty verdict and the judge sentenced Edwards to life in prison. He was sent to McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary in Steilacoom, Washington.

Seventeen years later, in March 1951, Edwards—now 64 and still imprisoned at McNeil Island—wrote a desperate letter. “Up ’til now you have never heard of me,” he began, and then repeated the protestations of innocence he’d been making ever since his arrest. He had affidavits from witnesses who’d said he could not have committed the murder. The White Mountain Apache Tribal Council had unanimously recommended his release from prison. Another suspect had even been found. Edwards had pleaded with authorities for a pardon or parole, but nothing he did could move them.

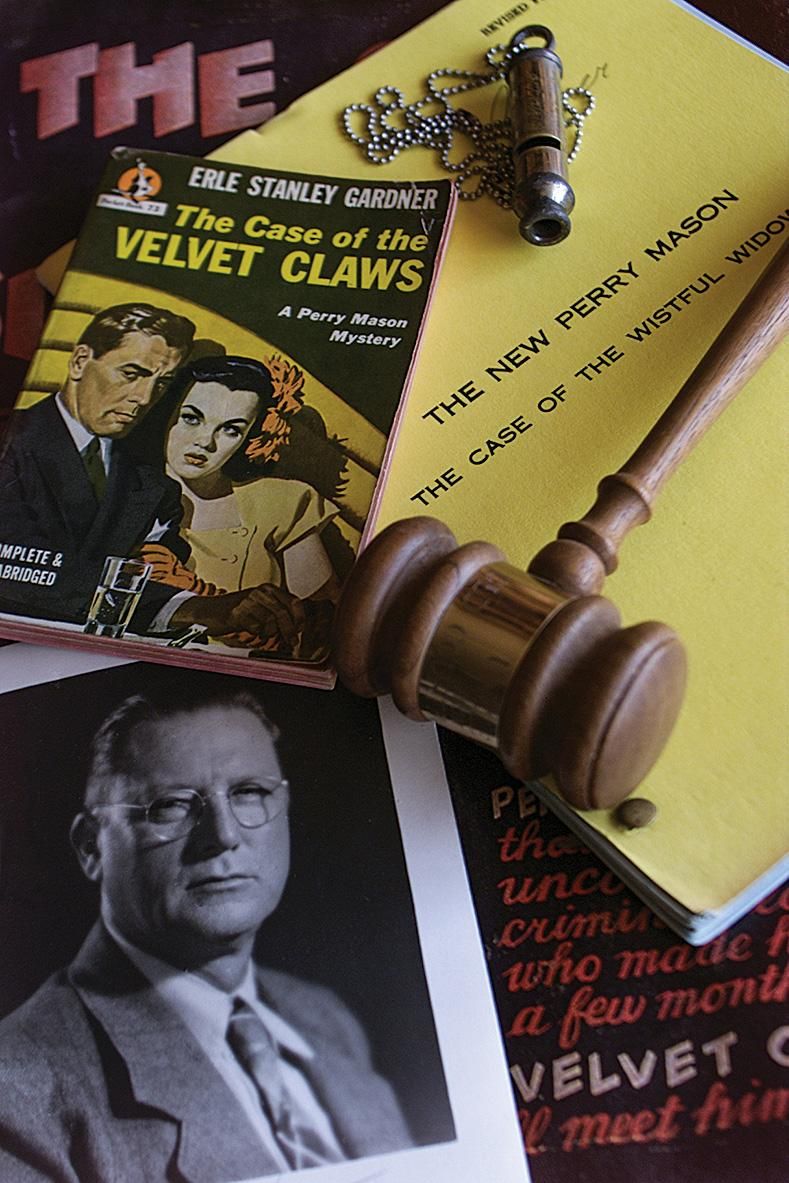

This letter was a last-ditch effort to avoid dying of old age behind bars. Edwards thought the man he was writing to could get him out. The man was Erle Stanley Gardner, the author of the Perry Mason mystery books.

At the time, Gardner was America’s best-selling author. He was also a lawyer, and soon after he received Edwards’ letter, he agreed to help. Thus began an unprecedented partnership between an imprisoned Apache holy man and a fiction writer who’d made the dramatization of crime a national obsession.

* * *

Until the day of Margaret’s murder, Edwards had spent his whole life on Indian reservations. His grandparents had been born in the same region when it was still part of Mexico. They’d lived in family groups that grew corn, beans and squash along waterways nearby.

His parents, born after the Mexican-American War in the recently annexed New Mexico Territory, spent their lives worrying about the increasingly hostile U.S. Army, which built a garrison at Fort Apache on the White Mountain tribe’s land. The Indians could no longer travel, trade or even raise crops freely.

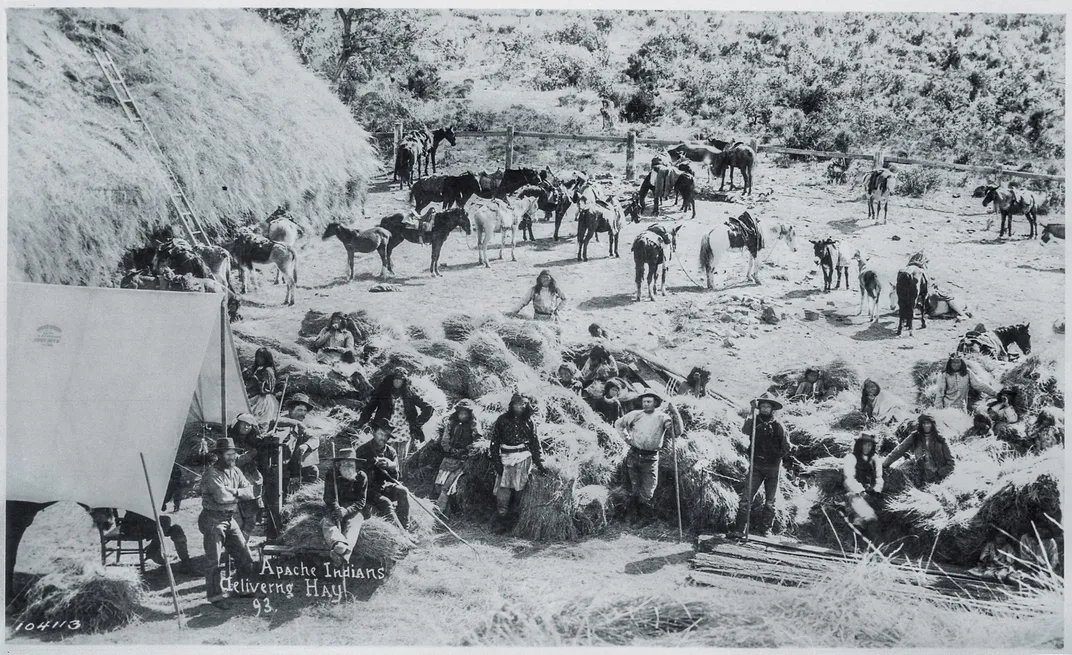

Nonetheless, a group of 50 White Mountain Apache men helped the U.S. defeat Geronimo in 1886. As a reward, the U.S. government allowed them to continue living on part of their ancestral territory, establishing the White Mountain Reservation (divided into the Fort Apache and San Carlos reservations). The reservation was a gorgeous expanse of mountains and valleys. Edwards was born there in the 1880s and given the name Pay-yay.

As a child, he was raised with traditional beliefs about male, female and animal deities who had created the world and given power and good fortune to the Apache people. But life on the Apache reservations was hard. Government food rations were insufficient. Starting in the 1890s, Indian children were required to attend schools where they had to shed cultural practices, from hairstyle to language. Edwards and his classmates were given Anglicized names.

But their geographic isolation allowed the White Mountain Apaches to keep some of their traditions. Edwards learned from his father, a medicine man, how to treat illnesses by tapping into the power of rattlesnakes. He also became skilled at tanning rattlesnake skins, and crafting hatbands and other goods from them. Blue dots tattooed along the bridge of his nose and on his chin soon signified his special talents as a practitioner of traditional Apache medicine.

In 1911, a young Lutheran missionary named Edgar Guenther arrived at the reservation. He and his wife, Minnie, would remain in the area for 50 years. Under the pastor’s tutelage, Edwards converted to Christianity and began working as an interpreter for church services. He was especially fascinated by a biblical passage, Numbers 21:4-9, that described God setting venomous snakes on the rebellious Israelites. He and the minister had a falling out after Guenther discovered that Edwards had been using the Guenther home to “entertain women,” says Guenther’s grandson, William Kessel, who was born and raised on the Fort Apache Reservation. “That became a problem for Silas throughout his younger life, entertaining the women.”

Around this time, new religious movements were rising among the White Mountain Apaches in response to disease, drought, food shortages, poverty and assaults on traditional life. Edwards began leading one of the most successful. He reported that he’d received a vision “in rays from above”—a set of 62 prayers recorded in graphic symbols. The symbols communicated not only words but also gestures and body movements. In 1916, Edwards proclaimed himself a prophet—more than a medicine man—and launched the Holy Ground religious movement, which stood apart from both Christian and traditional Apache religious practices.

The White Mountain Apaches called the movement sailis jaan bi’at’eehi, meaning “Silas John his sayings,” and Edwards conducted his first Holy Ground snake dance ceremony in 1920. Apaches began joining the movement in sizable numbers. By the early 1920s, Holy Ground had drawn so many followers that it had the potential to upend and revolutionize Apache life. Edwards’ healing ceremonies, often involving rattlesnakes and lasting for days, drew large crowds to consecrated locations at reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. Whites were not allowed to participate or observe.

Meanwhile, the police saw Edwards as a dangerous figure. He was arrested for assault and for violating Prohibition by selling liquor to fellow Indians, even as he was fined for holding snake dances. Local officials were watching him closely.

By 1933, the popularity of Holy Ground had leveled off, but Edwards continued to preach, which annoyed officials in the region. He’d been married for six years to his third wife, Margaret, an Apache woman who had children from a previous marriage. Meanwhile, as many people close to the couple noted with disapproval, Edwards was carrying on an affair with another woman.

At his trial, which took place at the federal courthouse in Globe, Arizona, Edwards was declared indigent and given a court-appointed lawyer, Daniel E. Rienhardt.

For the prosecution, Assistant U.S. Attorney John Dougherty introduced letters Edwards had written to the other woman and witnesses who described his argument with his wife on the night of her death. Others confirmed there had been blood on Edwards’ clothing, as Rienhardt’s notes from the trial recorded. The cast of a shoe print found near the victim’s body was brought into the courtroom and was said to match Edwards’ shoe. The prosecution even displayed part of Margaret’s skull—an act Rienhardt called prejudicial.

“I was fully convinced Edwards was not guilty,” Rienhardt later wrote in a letter to Gardner. A biochemist presented support for the defense, testifying that the blood found on Edwards’ clothing was smeared on the fabric, not splattered or dripped, which supported Edwards’ story.

But the strangest evidence was the rocks that bore Edwards’ initials. The prosecution told the jury that the initialed rocks were in keeping with a tribal tradition—that an Apache murderer left initials at the scene of a crime to prevent a victim’s soul from seeking retribution. Rienhardt argued that this was utterly false. Apaches didn’t leave their initials at murder scenes, and anyone familiar with Apache customs would attest to that. (The surviving notes from the trial do not show that any witness testified about the supposed tradition of leaving initials behind.) Besides, Rienhardt argued, why would Edwards be strenuously maintaining his innocence if he’d left his initials at the crime scene? When Edwards took the stand, though, the prosecution subjected him to a sarcastic and ridiculing cross-examination.

The trial and the jury’s deliberation took only a week. “A white man would have been freed in 15 minutes by the same jury that tried him,” Rienhardt wrote in a November 1933 statement, trying to get a new trial for his client. Rienhardt also maintained that the superintendent of the Indian reservation had welcomed the chance to take the influential shaman away from his followers. But there was no new trial, and Edwards would languish in prison for nearly two decades.

* * *

At the time Gardner got the letter from Edwards, he was living on a ranch in Temecula, California, about 60 miles northeast of San Diego and just outside the borders of a Pechanga Reservation. (Today, the ranch is part of the reservation itself.) His office was decorated with American Indian artwork, baskets, masks and moccasins. But Gardner, a Massachusetts native, had little knowledge of the religious life or cultural significance of the man who wrote to him from the McNeil Island Penitentiary.

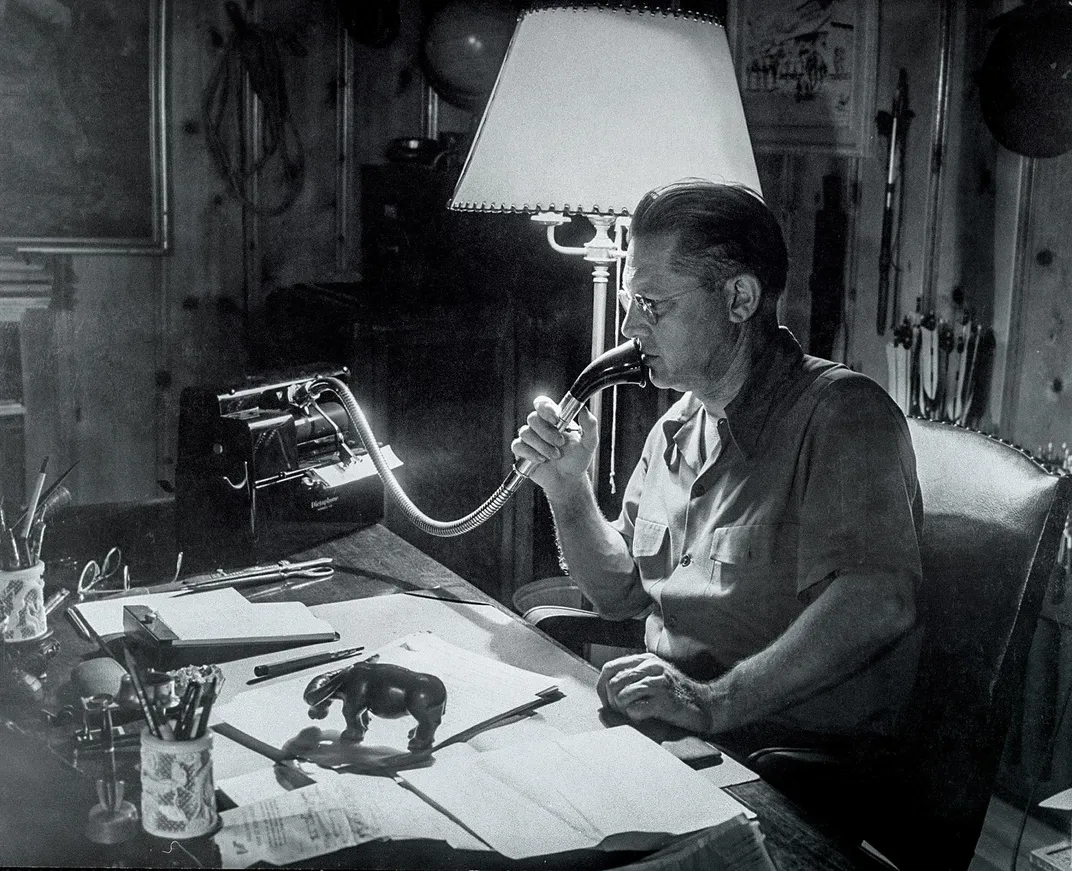

What Gardner did understand were the flaws in the prosecution’s case. A bespectacled man with a commanding gaze, Gardner had spent years practicing law in California. In the early 1920s, he’d started writing mystery stories for pulp magazines. He’d published his first Perry Mason novel one month after the murder of Edwards’ wife. Over the years, Perry Mason—a fictional defense attorney who usually defended innocent clients—became the center of a literary juggernaut, generating sales of more than 300 million books as well as a popular TV show.

Like the hero he’d invented, Gardner felt drawn to cases involving the wrongly accused. He believed America’s criminal justice system was often biased against the vulnerable. In the 1940s, Gardner used his fame and wealth to assemble what he called the Court of Last Resort, a group of forensic specialists and investigators who—like today’s Innocence Project at Cardozo School of Law—applied new thinking to old cases.

Gardner’s team rescued dozens of innocent people from executions and long prison terms. Among them were Silas Rogers, a black man sentenced to death for shooting a police officer in Petersburg, Virginia; Clarence Boogie, a victim of false testimony in a murder case in Spokane, Washington; and Louis Gross, who had been framed for murder in Michigan. Gardner persuaded Harry Steeger of Argosy magazine to regularly publish his articles about his organization’s findings. “We are busybodies,” Gardner declared in a letter to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. “If, on the other hand, citizens don’t take an active interest in law enforcement and the administration of justice, we are going to lose our battle with crime.”

The letter from the Apache shaman made a strong impression on Gardner. “This Silas John Edwards case has been preying on my mind,” he wrote to James Bennett, the director of the Bureau of Prisons at the U.S. Department of Justice, on May 2, 1952. “This man is a full-blooded Apache Indian. There is every possibility that he didn’t get justice at the hands of a jury who may not have understood Indian psychology, temperament and custom. I think we should investigate the case.”

Gardner met Edwards in prison a few months later, shortly after the Apache shaman had been transferred from McNeil Island to a federal prison camp near Wickenburg, Arizona. The prisoner appeared heavily muscled and younger than his years. “Outwardly he is stoic and calm,” Gardner later recalled. “His alert, attentive eyes miss no detail.” Gardner admired the fact that Edwards had a treasury of Apache tradition and medicinal wisdom stored in his mind. He asked Edwards about the most damning evidence in his case: the rock marked with his initials. “That is no custom to appease the spirit of [the] departed,” Edwards said, “but it is a very fine custom by which somebody can frame a killing on somebody else.”

At the end of their meeting, Edwards dipped his forefinger into a buckskin pouch that hung around his neck. It contained sacred pollen, called hadndin, which Edwards dabbed on Gardner’s forehead in the shape of a cross. He made a similar mark on the crown of Gardner’s hat. (The Holy Ground movement incorporated some elements from Christianity, including the iconography of a cross.) Edwards told Gardner that this ritual would keep him physically and spiritually resilient. “Our medicine was strong,” Gardner concluded after the meeting, reflecting on the new details he’d learned about the case. He agreed to investigate it himself.

* * *

In the fall of 1952, Gardner and another Court of Last Resort investigator, Sam Hicks, arrived at the U.S. District Court building in Tucson to exhume the records from Edwards’ trial. Among the files was a cache of letters that Edwards had written to his lover. In one of them, Edwards recalled a time he and the woman met in a canyon and “the tracks of our feet in the sand were covered by our shadows.” Gardner admitted to feeling some sympathy when he read the letters. He later described the affair in Argosy as a “brief emotional flare-up, a physical attraction for the comely young woman who had such a graceful, streamlined figure.” Edwards insisted that he’d never stopped loving Margaret, that his affection for his wife had “burned with a slow, steady flame that represents the mature companionship of adults who have shared many of life’s vicissitudes.”

The prosecution had asserted that Edwards had grown tired of his wife, found a younger woman who interested him more and murdered Margaret to get her out of the way. But even when Gardner considered the case through that lens, he found the evidence flimsy. “How absurd it is to think that a man would scratch his initials on a rock, leave it at the scene of a murder, and then protest his innocence,” Gardner wrote in Argosy. “One can well imagine how Sherlock Holmes would have curled his upper lip in disgust at the police reasoning that would have thought this rock an indication of guilt.”

Gardner and Hicks drove to Globe, where they met Edwards’ defense lawyer, Daniel Rienhardt, now in his mid-60s, and Robert McGhee, another attorney who had assisted Edwards. Both remembered the Edwards case. (Rienhardt admitted he was a Perry Mason fan and had recently bought a copy of The Case of the Moth-Eaten Mink.)

Together, the lawyers and investigators drove into the mountains north of Globe. They passed through groves of junipers and cedars, crested the high peaks, and descended into the Salt River Canyon. Twisting roads and high bridges brought them to a plateau where the pavement stopped and dirt roads led into the Fort Apache Reservation.

At the reservation’s police station, Rienhardt asked an Apache officer whether he had ever heard of a custom that compelled a murderer to leave initials near a victim’s body. “In only one case,” the officer replied, “and that happened to be the murder of my mother.” The policeman, Robert Colelay, was Margaret Edwards’ son from an earlier marriage. And he told the investigators that he believed Silas John Edwards did not kill her.

Apache officers escorted the group to the key locations in the case, including the murder site at the edge of the trail. This section of the reservation had not changed much in the years since Margaret’s death. The roads were still rough and many White Mountain tribal members still lived in tepees nearby. Gardner interviewed surviving witnesses and others who had knowledge of the murder. He sketched maps to understand the geography. The visit ended with one of the group’s Apache guides producing a pouch like the one Edwards wore around his neck. He painted crosses in yellow powder on Gardner’s shoulder, forehead and hat.

Nobody Gardner met at the reservation had heard of an Apache tradition involving initials left at a murder scene. One person also challenged the shoe print mold, asserting that a police officer had forced Edwards’ shoe into the original track before the cast was made. “The evidence which convicted him was pathetically inadequate as well as absurd,” Gardner concluded. “The facts strongly indicate an innocent man has been imprisoned.”

Gardner contacted each member of the U.S. Board of Parole to argue for the release of the Apache shaman. Without the inflammatory evidence of Edwards’ adultery, he argued to parole commissioner Joseph Dewitt, “no jury would have returned a verdict of guilty.”

Gardner told the superintendent of the Arizona prison that the Apaches seemed to have “a pretty good general idea” who did murder Margaret. Gardner refused to publish the suspect’s name, but here it can be revealed for the first time in print: He was a White Mountain Apache named Foster James.

The evidence supporting James’ guilt is considerable. One member of the Court of Last Resort, Bob Rhay (who went on to become the longest-serving superintendent of Washington State Penitentiary), spent time looking into it more deeply. “Foster James has admitted on several occasions that he is the actual murderer,” Rhay wrote in a report preserved among Gardner’s papers at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas. He referred to “an affidavit from a Mr. and Mrs. Anderson, in which Mrs. Anderson says that Foster James admitted to her, while he was attacking her, that he had killed Mrs. Edwards.” (Efforts to find surviving friends or relatives of Foster James and include their opinions in this account were unsuccessful. He had no children.)

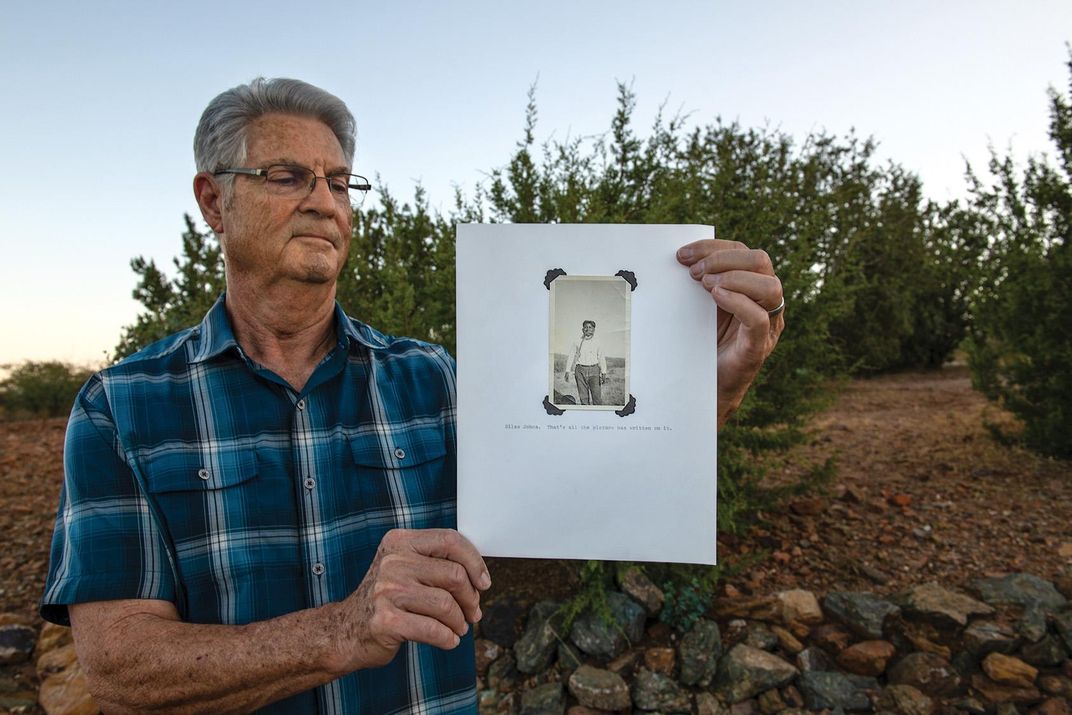

Kessel, an anthropologist and the grandson of the Lutheran minister who converted Edwards to Christianity, says it was conventional wisdom on the reservation that it was James who had killed Margaret. When Kessel interviewed a number of Apache elders for his academic research on the tribe’s religious movements, they said they believed that Edwards was innocent. Just one interviewee departed from that version of events: Foster James himself.

The tribal chairman had asked Kessel never to mention the accusations against James until after James, Edwards and others close to them died—a promise Kessel would keep. James died in 1976.

For Gardner’s part, he’d noticed that tribal members seemed fearful when they discussed James. “None of these Indians dare to raise their voices above a whisper,” he wrote. “None of them will permit their names to be quoted. The murder of Mrs. Edwards was a ruthless, bloody affair and there is still a silent terror which stalks the Indian reservation.” But more than fear kept the Apaches’ lips closed. In the community of the reservation, with its blood kinships and close relationships, the Apaches did not want to out one of their own.

* * *

On August 1, 1955, Silas John Edwards walked out of prison and returned to reservation life. Though Edwards was already eligible for parole, Gardner’s efforts apparently tipped the scale and persuaded the parole board. Edwards shared the news with Gardner in a letter. According to Gardner, the first thing the newly freed man asked him to do was to thank the readers of Argosy. It’s not known how many of the magazine’s devoted readers wrote to federal officials to protest Edwards’ continuing incarceration, but the response may have been considerable.

Edwards’ followers had kept his movement alive the whole time he was incarcerated, and when he returned to the reservation, he resumed his role as a prophet, albeit with a lower profile. During the 1960s, he led his last Holy Ground snake dance. Soon afterward, he fell back into the more modest role of a traditional medicine man.

Gardner visited Fort Apache again, about a decade after Edwards’ parole. At first, he didn’t recognize the septuagenarian, who was chopping wood: “The man looked even younger than when we had seen him years before in prison.”

Kessel remembers visiting Edwards toward the end of his life, when he was living at an American Indian convalescent home in Laveen, Arizona. “There was no grudge against anybody for anything,” Kessel recalls. “He was a gentleman to the end.” Edwards died in 1977.

The religious movement he founded has at least one practitioner, Anthony Belvado, who was born on the San Carlos Reservation and makes traditional musical instruments. He carries the same kind of buckskin pouch that Edwards wore around his neck, filled with hadndin, and practices as a healer in the Holy Ground tradition.

Life on Arizona’s reservations is still hard, decades after Edwards’ time. More than 40 percent of White Mountain Apaches live in poverty. Covid-19 has devastated the community—at one point, White Mountain Apaches were being infected at ten times the rate of other Arizonans.

And wrongful convictions remain a problem in Indian country. In 2015, an Alaska judge ordered the release of the “Fairbanks Four,” Indian men who had spent 18 years in prison for a murder they hadn’t committed. A 2016 report from the University of South Dakota found that Indians were dramatically underrepresented on juries, partly because of a cumbersome process that makes it difficult for reservation Indians to register to vote.

Meanwhile, the legacy of Perry Mason lives on. The Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor has cited the character as an influence, quoting a line spoken by a prosecutor on the show: “Justice is served when a guilty man is convicted and when an innocent man is not.” This past June, 50 years after Gardner’s death, HBO premiered a new Perry Mason television series. For many Americans, the fictional defense lawyer remains a symbol of due process done right.

The Edwards story was “one of the most peculiar murder cases that we have ever investigated,” Gardner said. The invention of a false Indian custom, and the jury’s willingness to believe it, landed an innocent man behind bars for more than 20 years. “If I were writing of this case as a work of fiction,” Gardner told the readers of Argosy, “I would call it The Case of the Autographed Corpse.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/89/16893a69-6fd6-4817-be61-98bfaad73af1/mobileopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/96/e696bfdd-81e7-423f-81f2-a996cc66ed3b/opener.jpg)