Catherine the Great’s Lost Treasure, the Rise of Animal Rights and Other New Books to Read

These five September releases may have been lost in the news cycle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/68/f168c17c-f5e9-4469-b708-c16c5ea6e4ec/booksweek11.png)

By the end of her reign, Catherine the Great had acquired more than 4,000 paintings, 38,000 books, 10,000 engraved gems, 16,000 coins and medals, and 10,000 drawings. But as writers Gerald Easter and Mara Vorhees point out in The Tsarina’s Lost Treasure, this collection—which later formed the foundation of the State Hermitage Museum—could have been even greater. A cache of Dutch masterpieces acquired by the art-loving Russian empress vanished when the ship carrying them sank in 1771 with its priceless artwork aboard.

The latest installment in our series highlighting new book releases, which launched in late March to support authors whose works have been overshadowed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, explores the loss and rediscovery of Catherine the Great's sunken merchant ship, a leader of the fledgling animal rights movement, the stories of three daughters of World War II leaders, humanity’s connection to the cosmos, and the life of “Black Spartacus” Toussaint Louverture.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing-appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

The Tsarina's Lost Treasure: Catherine the Great, a Golden Age Masterpiece, and a Legendary Shipwreck by Gerald Easter and Mara Vorhees

When Dutch merchant Gerrit Braamcamp died in June 1771, his executors held an estate sale featuring what Easter, a historian, and Vorhees, a travel writer, describe as “the most dazzling assemblage of Flemish and Dutch Old Masters ever to reach the auctioneer’s block.” Highlights included Paulus Potter’s Large Herd of Oxen, Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee and Gerard ter Borch’s Woman at Her Toilette. But one work eclipsed the rest: The Nursery, a 1660 triptych by Rembrandt student Gerrit Dou, who was—at the time—widely believed to have surpassed his teacher’s already prodigious talents.

Following an unprecedented bidding war, Catherine’s representatives secured The Nursery, as well as a number of other top lots, for the empress, a self-proclaimed “glutton for art.” The cultural trove departed Amsterdam on September 5, stowed in the cargo hold of the Saint Petersburg-bound Vrouw Maria alongside sugar, coffee, fine linen, fabric and raw materials for Russian craftsmen.

Just under a month after it left port, the merchant vessel fell afoul of a storm in the waters off of modern-day Finland. Though all of its crew members escaped unscathed, the Vrouw Maria itself sustained significant damage; over the next several days, the ship slowly sank beneath the waves, consigning its contents to the ocean floor.

The czarina’s efforts to recover her artwork failed, as did all salvage missions undertaken over the next 200 years. Then, in June 1999, an expedition led by the aptly named Pro Vrouw Maria Association located the wreck in a state of almost perfect preservation.

The Tsarina’s Lost Treasure deftly catalogs the fierce legal battles that ensued following the ship’s discovery. Buoyed by the tantalizing possibility that the vessel’s cargo remained intact, Finland and Russia both laid claim to the wreckage. Ultimately, the Finnish National Board of Antiquities decided to leave the Vrouw Maria in situ, leaving the question of the artworks’ fate unresolved. As Kirkus notes in its review of the book, “[I]t’s an entertaining yarn whose ending is yet to be written.

A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement by Ernest Freeberg

For most animals, life in Gilded Age America was fraught with exploitation and violence. Workers pushed horses to the limits of their endurance, dogcatchers drowned strays, and merchants transported livestock on lengthy journeys without food or water. Dog fighting, cockfighting, rat baiting and other similarly abusive practices were also common. Much of this mistreatment stemmed from the widespread belief that animals lacked feelings and were incapable of experiencing pain—a view that Henry Bergh, a wealthy New Yorker who’d previously served as a diplomat in imperial Russia, strongly contested.

Bergh launched his campaign for animal rights in 1866, establishing the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) as a nonprofit with the power to “arrest and prosecute offenders,” per Kirkus. As Ernest Freeberg, a historian at the University of Tennessee, writes in his new biography of the unlikely activist, some Gilded Age Americans responded with “a mix of applause and mockery," while others “who resented this interference with their economic interests, comforts, or conveniences” fiercely resisted Bergh’s call to action.

One such opponent was circus magnate P.T. Barnum, who’d built his empire by exploiting animals and people alike. Pitted against Barnum and other leading figures of the period, the naturally theatrical Bergh often found himself subjected to ridicule. Critics even labeled him a “traitor to his species.” Despite these obstacles, Bergh persisted in his campaign, arguing that while humans had the right to use animals (he personally was fond of both turtles and turtle soup), they lacked the authority to abuse them. By the time of Bergh’s death in 1888, notes Kirkus, “[M]ost states were enforcing ASPCA–backed anti-cruelty laws, and [the] universal feeling that animals did not suffer had become a minority view.”

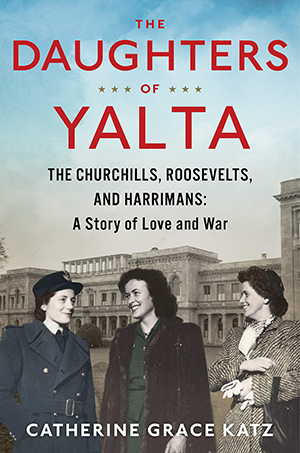

The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War by Catherine Grace Katz

The February 1945 Yalta Conference is perhaps best known for producing a photograph of three Allied leaders—U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin—posing alongside each other as if they were the best of friends. In fact, these blithe smiles belied the contentious nature of the peace summit, which acted less as an affirmation of alliance than as a predecessor to the Cold War.

In The Daughters of Yalta, historian Catherine Grace Katz offers a behind-the-scenes look at the eight-day conference through the eyes of Roosevelt’s daughter, Anna; Churchill’s daughter Sarah, who was then serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force; and Kathleen Harriman, daughter of American ambassador to the Soviet Union Averell Harriman. Each played a key role in the meeting: Anna helped her father hide his rapidly declining health, while Sarah assumed the role of Churchill’s “all-around protector, supporter, and confidant,” according to Katz. Kathy, a competitive skier and war correspondent, actually learned Russian in order to act as Averell’s “de facto protocol officer,” notes Publishers Weekly.

An array of personal ties compounded the many political factors already at play during the conference. Churchill’s daughter-in-law Pamela was having an affair with Averell, for instance, and Kathy had had a brief affair with Anna’s married brother. But while Katz dedicates ample space to Yalta’s interpersonal intrigue, her main focus is the women’s roles as “daughter diplomats. As she explains on her website, “Their fathers could work through them to gather information, to deliver subtle but important messages that could not be explicitly expressed by a member of the government, and to give the leaders plausible deniability on thorny diplomatic issues in which they could not be directly involved.”

The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars by Jo Marchant

Humans’ fascination with the night sky is as old as civilization itself, writes Smithsonian contributor Jo Marchant in The Human Cosmos. Citing case studies as varied as Ireland’s Hill of Tara, the Native American Chumash people, ancient Assyrians who associated lunar eclipses with their king’s demise, and drawings of what could be constellations at Lascaux Cave, the journalist traces the trajectory of humanity’s relationship with the stars from prehistoric times to the present, covering 20,000 years in just 400 pages.

Marchant’s overarching argument, according to Publishers Weekly, is that technology “separates people from the actual world.” By relying on GPS, computers and other modern tools, she suggests that society has created a “disconnect between humanity and the heavens.”

To correct this imbalance, Marchant prescribes a shift in perspective. As she explains in the book’s prologue, “I hope that zooming out to survey the deep history of human beliefs about the cosmos might help us probe the edges of our own worldview and perhaps look beyond: How did we become passive machines in a pointless universe? How have those beliefs shaped how we live? And where might we go from here?”

Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture by Sudhir Hazareesingh

As alluded to by its title, Sudhir Hazareesingh’s latest book centers on a larger-than-life figure: Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian general and revolutionary whom the historian describes as the “first black superhero of the modern age.” Born into slavery around 1740, Louverture worked as a coachman on a plantation in Saint-Domingue (later Haiti). “[I]ntelligent, daring and athletic,” writes Clive Davis in the Times’ review of Black Spartacus, he gained his freedom in the 1770s and proceeded to embark on a number of business ventures, including renting a coffee plantation staffed by at least one enslaved individual.

In 1791, enslaved people living on Hispaniola, the French-controlled half of Saint-Domingue, revolted. Though Louverture initially stayed out of the conflict, he was eventually spurred to action by both his Catholic religion and Enlightenment belief in equality. Given command of thousands of formerly enslaved rebels, the burgeoning military man soon emerged as one of the movement’s key leaders.

Afraid that the unrest would spread to its own colony of Jamaica—and eager to cause trouble for its European neighbor—the British government sent in troops to put down the rebellion. France, faced with the possibility of defeat, sought to secure the rebels’ loyalty by abolishing slavery across its colonies. Louverture, in turn, allied with his former enemy, fighting Spanish and British colonizers on behalf of France.

By the end of the century, notes David A. Bell for the Guardian, “[H]e had outmaneuvered a series of French officials, overcome black rivals, emerged as the colony’s uncontested strongman, and brought it to the brink of independence.” In doing so, Louverture attracted the attention of newly minted French leader Napoleon Bonaparte, who sent 20,000 French troops to reassert control over the island. Though the French campaign ultimately failed, Napoleon did manage to end his rival’s grasp on power. Promised safe passage to peace talks, Louverture instead found himself arrested and imprisoned in France, where he died in 1803—just one year before Haiti officially won its independence.

Black Spartacus draws on archival documents housed in Britain, France, the United States and Spain to present a comprehensive portrait of an oft-mischaracterized man. “Toussaint,” writes Hazareesingh, “embodied the many facets of Saint-Domingue’s revolution by confronting the dominant forces of his age—slavery, settler colonialism, imperial domination, racial hierarchy and European cultural supremacy—and bending them to his will.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)