Cave Markings Tell of Cherokee Life in the Years Before Indian Removal

Written in the language formalized by Sequoyah, these newly translated inscriptions describe religious practices, including the sport of stickball

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/7d/fe7dfe20-4bdc-4308-a457-4110caa73815/figure-2_final.jpg)

On April 30, 1828, a Cherokee stickball team stepped into the underworld to ask for help.

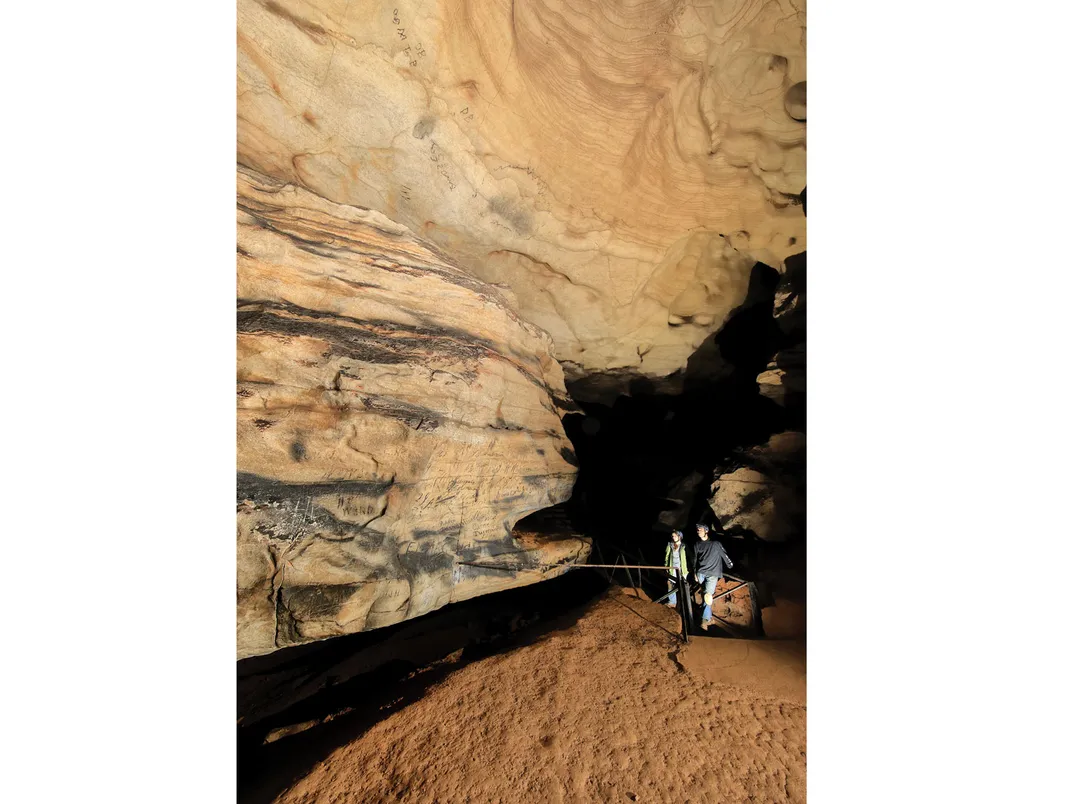

Carrying river-cane torches, the men walked into the mouth of Manitou Cave in Willstown, Alabama, and continued nearly a mile into the cave's dark zone, past impressive flowstone formations in the wide limestone passageway. They stopped inside a damp, remote chamber where a spring emerged from the ground. They were far from the white settlers and Christian missionaries who had recently arrived in northeastern Alabama, putting increasing pressure on Native Americans to assimilate to a Euro-American way of life. (In just a few years President Andrew Jackson would sign the Indian Removal Act that would force the Cherokee off their land and onto the Trail of Tears.) Here, in private, the stickball team could perform important rituals—meditating, cleansing and appealing to supernatural forces that might give their team the right magic to win a game of stickball, a contest nicknamed "the little brother of war."

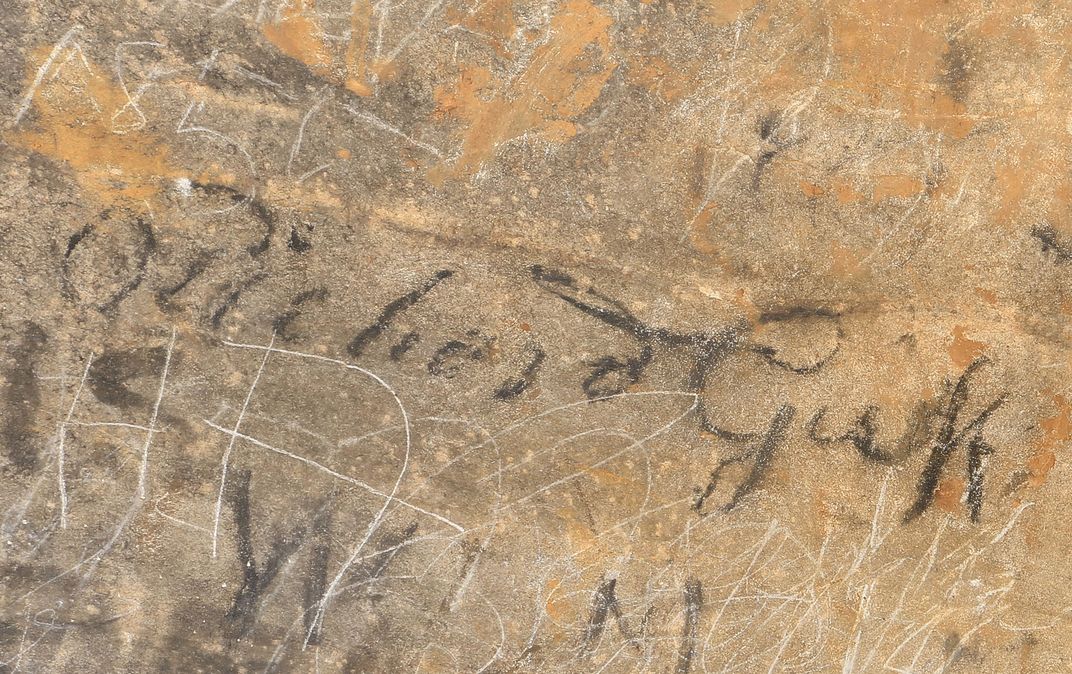

This spiritual event, perhaps ordinary for the time but revelatory now, only recently became known because of a set of inscriptions found on the walls of the cave. A group of scholars have now translated the messages, left by the spiritual leader of the stickball team, and describe them in an article published today in the journal Antiquity. Prehistoric ancestors of the Cherokee left figurative paintings inside caves for centuries, but scholars didn't know that Cherokee people also left written records—documents, really—on cave walls. The inscriptions described in the journal article offer a window into life among the Cherokee in the years immediately before they would be forcibly removed from the American southeast.

"I never thought I would be looking at documents in caves," says study co-author Julie Reed, a historian of Native American history at Penn State and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation.

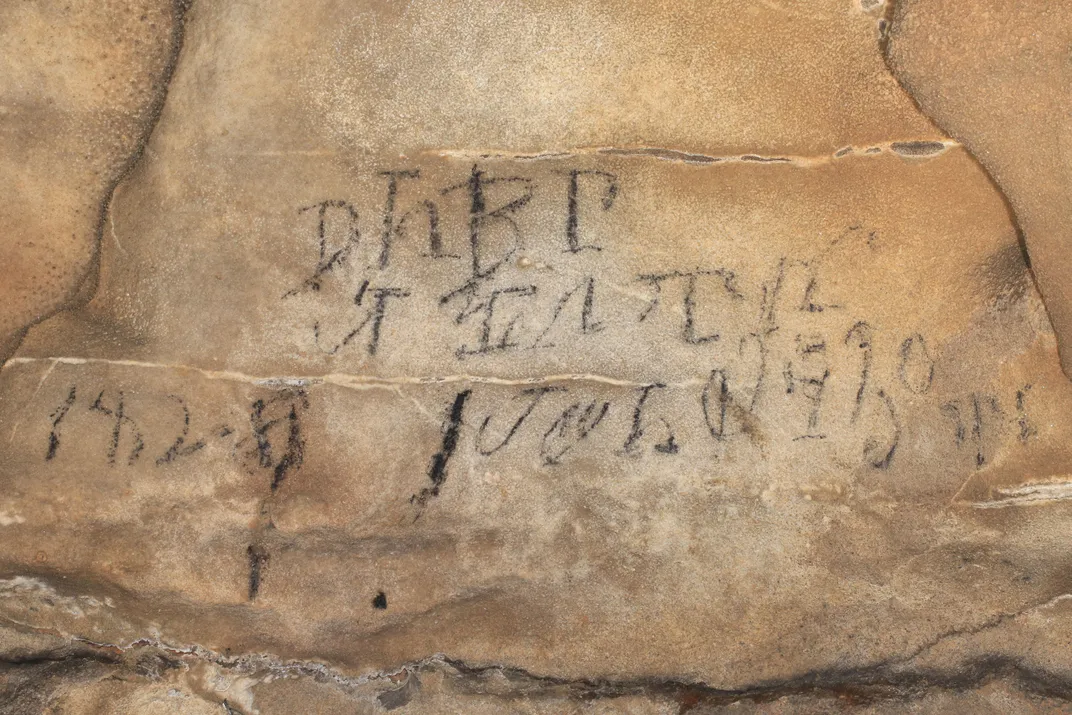

The inscriptions were written in the Cherokee syllabary, a writing system that was formally adopted by the Cherokee just three years prior in 1825. It quickly allowed a majority of the tribe to become literate in their own language, and the Manitou Cave inscriptions are among a few rare examples of historic Cherokee writing recently found on the walls of caves.

"Cavers have been going in caves in the Southeast for a really long time, looking for more prehistoric artwork," says Beau Carroll, the lead author of the study and an archaeologist with the tribal historic preservation office of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. "For you to be able to pick out actual syllabary you have to be familiar with it. I think it's all over the place. It's just that nobody's been looking for it.”

In 2006, a historian and a photographer had been documenting the English-language signatures and graffiti in Manitou Cave, which had become a tourist attraction by the late 19th century. They recognized writing that didn't look like English and showed photos to Jan Simek, an archaeologist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, who studies rock art in the region.

The cave, which is on private land, was sold shortly after the first inscription was photographed, Simek says, and the new owner of the cave would not allow access to anyone. So Simek and his colleagues couldn't document the writings for themselves until the cave changed hands again in 2015.

"Prehistoric people made art inside—sometimes deep inside—many caves in the area, and in some cases, those go back 6,000 years," Simek says. "The writing was important because it suggested some continuity with a tradition that we knew went very far back in the past, so we started to record this stuff. It was a writing system that we couldn't read or write so we asked Cherokee scholars to come help us do it."

At the dawn of the American Revolution, the Cherokee homeland covered parts of Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. Just after the war, groups of Cherokee who had fought with the British fled contact with the United States and took up residence in Alabama; many took refuge in Willstown, now known as Fort Payne after the U.S. fort that was established there in 1830 as a concentration camp for the Cherokee during Indian Removal. Among Willstown's new residents was Sequoyah, a Cherokee silversmith and scholar, sometimes named as George Guess.

Sequoyah thought it would be useful for the Cherokee to have a written language, and he invented a syllabary—easier to learn than an alphabet—made up of symbols for all 85 syllables in the spoken language. After its adoption as the Cherokee Nation's formal writing system, the syllabary went into wide use. The first Native American newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, was published in syllabary and English starting in February 1828.

"The syllabary is a new innovation in Cherokee society, and it's occurring at the same moment the U.S. government is adamantly pushing its 'civilization' policy—it wants them to Christianize, it wants them to seek English-language education, it wants them to change their gender roles relative to farming so that men are farming and women are relegated to the home," says Reed.

The early 19th century was a time of upheaval, especially in Willstown, where the population was growing as more Cherokee people arrived, displaced from their homeland. Among the Cherokee vigorous debates broke out about political and social interaction with whites, and mixed embraces of various "civilization" features.

"The great part of Sequoyah's invention is that on one hand it is a trapping of civilization—a written language—and on the other hand it's an affront to the civilization policy because it is the Cherokee language and it enables literacy so quickly that it does the work of revitalizing older pieces of Cherokee tradition," Reed says.

As the paper in Antiquity describes, one charcoal translates to "leaders of the stickball team on the 30th day in their month April 1828." A few meters away, another inscription on the wall refers to "we who are those that have blood come out of their nose and mouth," and it is signed by Richard Guess, Sequoyah's son, and one of the first to learn the syllabary. The researchers have interpreted these texts as records of stickball rituals, led by Guess, before the men went out onto the field, and after the game, when they were bruised and bloodied from a touch contest.

Stickball was a game similar to lacrosse, with two teams playing on an open field trying to move a ball into the opposition's goal using sticks with nets at the end. It could last for days and was sometimes used to settle disputes between communities, but the sport also had a ceremonial importance to the Cherokee. The players performed rituals before and after the contests that replicated rituals that would need to happen before and after war, and access to sacred sources of water was important during these ceremonies.

According to Carroll, the archaeologist and co-author, stickball contests were essentially seen as a face-off between two medicine men. "Whoever's magic is the strongest is the one who's going to win the game," says Carroll, who has played stickball himself.

Adds Reed: "These games could get extremely violent and sometimes resulted in death for the players. Anytime blood is in involved, that substance being outside the body can throw the world out of balance. So ceremonies have to be performed to bring the world [back] into balance."

The researchers suspect that this particular team went so far into the darkness of the cave because they sought seclusion from the Christian missionaries who greatly disapproved of stickball and its associated religious activities. (Carroll also says it probably would have been important for the players to be far away from the opposing team.)

President Jackson's Indian removal policy became law just a few years after that game, in 1830. Some of the players might have been interned at Fort Payne during this campaign of ethnic cleansing, and by 1839, most Cherokee were forced off the land into new "homes" in reservations in Oklahoma. Manitou Cave was opened as a tourist attraction in 1888, but its indigenous history was largely unknown. Modifications to make the passages more tourist-friendly likely destroyed archaeological deposits that might have held clues about the cave's past uses by Native Americans.

George Sabo, director of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, who wasn't involved in the study, says the new evidence "anchors important events in early 19th-century Cherokee history onto a specific locale comprising one element of a larger, sacred landscape."

A few other syllabary inscriptions have been recorded in Manitou Cave, and in other caves nearby. Not all of the syllabary translations from Manitou Cave have been included in the paper. Carroll says he consulted with fellow community members to decide what texts should and should not be published for a non-Cherokee audience, as inscriptions contain descriptions of spiritual ceremonies that were not intended for public consumption. Manitou Cave, like many caves that contain Native American rock art in the southeast, is now on private land. Its current steward bought the cave and surrounding land in 2015 with the intention of preserving the site. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians contributed funds for a strong steel gate at the cave entrance to protect the inscriptions.

The authors of the study have emphasized the importance of the collaboration between white archaeologists and Cherokee scholars in studying the inscriptions.

"We would not have been able to develop as rich and textured a vision of what this archaeological record means without collaborating with our Native American colleagues," says Simek.

"Cherokee people are still here, we haven't gone anywhere, we're interested in our history and we can contribute to science and this paper's proof of that," Carroll says. "It doesn't make any sense to me to do all this historical research and archaeology but you don't include the living descendants of the people you're studying."