A Century Before the Residents of a Remote Island Killed a Christian Missionary, Their Predecessors Resisted the British Empire

When a white clergyman tried to punish captive Andamanese for their supposed misdeeds, they slapped him back

:focal(1000x662:1001x663)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/97/84975a39-7177-4ba8-af92-ba52c05f1794/ch2_1.jpg)

The Andaman Islands, a remote tropical archipelago in the Indian Ocean, drifted on the margins of the world’s consciousness until 2018, when the fact of their existence suddenly went viral. Their transformation into a global sensation happened after a young American evangelical missionary named John Allen Chau landed on North Sentinel Island, a scrap of land inhabited by a tribe of hunter-gatherers still living in total isolation.

The Sentinelese, as they are called by outsiders—no one knows how they refer to themselves, nor even what language they speak—responded to Chau’s overtures by killing him on the beach with their bows and arrows. When the story hit international networks and social media, many people hailed the islanders as heroes for standing their ground against the forces of modernity and religious aggression. News headlines and online posts continue to refer to North Sentinel as one of the most isolated places in the world, perhaps the last true terra incognita on Earth.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/3e/b13e6e89-1f59-4f07-afb5-589844b21b53/23551303_10159568716250634_7261440719817472048_o.jpeg)

Yet the long-buried history of the Andaman archipelago, which includes several hundred islands in addition to North Sentinel, lifts the curtain on the mystery. It reveals that the Sentinelese are not so much undiscovered as they are in hiding—probably because they are aware of the fates that befell neighboring tribes.

For nearly a century, the Andamans, now a territory of India, were part of the British Empire, settled in 1858 as a penal colony: a place of permanent exile for political dissidents and other prisoners of the Raj. Though the colonizers never occupied North Sentinel Island, they encountered similar tribes scattered through the rest of the archipelago. The British arrived in the Andamans bent upon dominion but determined that their conduct would be above reproach. Indeed, the first British superintendent of the Andamans, when dispatched to the archipelago, endeavored to demonstrate that his intentions were “of the most friendly character.” Instead, within just a few years, the Andaman Islands became an imperial heart of darkness worthy of a Joseph Conrad novel.

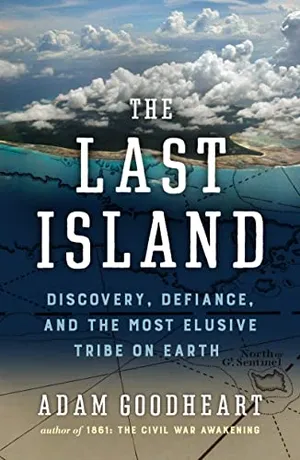

The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth

As the web of modernity draws ever closer, North Sentinel Island represents the last chapter in the Age of Discovery—the final holdout in a completely connected world.

In early 1863, a small party of British Royal Navy brigadesmen returned to their base at Port Blair, the colonial capital on the largest island in the archipelago, with a shocking report. Dispatched to an Andamanese camp “to establish friendly relations” with the locals, according to an 1899 history written by British officer Maurice Vidal Portman, the men said the inhabitants had suddenly turned hostile, seized a sailor named James Pratt, pinned him to the ground and shot him to death with their arrows as the other brigadesmen watched in horror. The soldiers loosed a volley or two of musket fire at the mass of agitated native inhabitants and made a hasty retreat to their longboat.

The colony’s superintendent at the time was not a man to brook any such insubordination. Colonel Robert Christopher Tytler was a hard-eyed, blunt-spoken martinet whose lifelong career in the Bengal Army—he had enlisted as a teenager—accustomed him to far worse horrors than this.

As a young lieutenant, he had first seen combat in the Afghan War, helping to avenge the notorious massacre near Kabul in 1842, when Afghan tribesmen slaughtered an entire British garrison after promising them safe passage back to friendly lines.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/df/c3dfcfa1-1d4e-4812-8954-bf0929229bfa/harrietroberttytler-2.jpeg)

More recently, Tytler and his young wife, Harriet Tytler—she eight months pregnant, with two small children at her side—had narrowly escaped Delhi in 1857, when the sepoys, or Indian infantrymen, mutinied. They had seen wagons laden with corpses of slain officers; heard the screams of suspected spies impaled on red-hot pokers; fled the city by night as their house and all their possessions, together with the rest of the army cantonment, went up in flames. The redoubtable Harriet gave birth in the back of a bullock cart a few days later, amid the din of nearby shellfire. (In appreciation of his wife’s sangfroid, the colonel later named the highest point in the hills above Port Blair in her honor: Mount Harriet.)

Tytler had accepted the Andaman appointment grudgingly, certain that something better would come his way soon. Nothing did. His wife, despite her fortitude in the retreat from Delhi, now languished in their official residence, plagued by a relentless succession of ailments. Irritated and impatient, the Tytlers—like many British functionaries who ended up in that squalid and inhospitable post, which was essentially one large prison camp—bore up as best they could, hating the place.

When news of Pratt’s murder reached the colonel, he saw it as simply another instance of native malfeasance, one that demanded swift and severe justice. But Tytler was a man to do things by the book, so instead of ordering a wholesale massacre, he wrote to the authorities in Calcutta, suggesting the guilty Andamanese be captured and punished. (In a letter, he referred to the Andamanese as “a race of treacherous, cold-blooded murderers, assuming the garb of friendship for the purpose of carrying out their diabolical plans.”) Within a few weeks, his troops had successfully captured the suspected ringleaders of Pratt’s murder, two native men named Tura and Lokala. They nicknamed the pair “Jumbo” and “Snowball,” bringing them back to Port Blair in fetters.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/99/17996292-1f82-4b02-ad52-cfc66230babd/screenshot_2023-09-22_at_113001_am.png)

Then a fact emerged that should have changed everything: Pratt had been in the act of raping an Andamanese woman—Tura’s wife—when he was killed. At this news, sharply worded communiqués from the Viceroy’s Executive Council, the governing cabinet of British India, arrived on Tytler’s desk, ordering him to stand down from his plans for “a general hunt after the aborigines.” The messages were laden with phrases like “unfortunate occurrences,” “interests of humanity” and “much regret.” But by that point, the two Andamanese were in the colonel’s custody, and he did not intend to let them go back to their own people. He saw an opportunity here, and he intended to take it. Only by civilizing these “savages,” he believed, could their race be properly brought to heel.

So instead of executing Tura and Lokala for their actions, the colonel simply kept them in fetters in the naval barracks for several months—determined to punish any violent transgression against a white man, whether provoked or not—then released them from their chains and treated them almost as honored guests.

He had a special house built for them on Ross Island, appointed convict servants to look after their needs, and provided all the food and tobacco that they wished. Tytler also placed them under the care of Port Blair’s chaplain, one Reverend Henry Fisher Corbyn, a young Anglican priest with a divinity degree and impeccable references. Corbyn commenced teaching them basket weaving and the English alphabet, both of which the Andamanese displayed admirable aptitude for. The only privilege they were not allowed was that of returning to their homes and families.

The English soon gave Tura and Lokala’s house a cozy-sounding name: the Andaman Home. Soon—perhaps unexpectedly—the two were joined by others. The British had always remarked upon the fondness the Andamanese showed for one another, and their sorrow at parting from friends and relatives. Now it appeared that the men’s loved ones must have been pining for them. One day, a woman and child made their way across the harbor to Ross Island. She was evidently Tura’s wife—recently the victim of Pratt’s assault—and the child was their son. The Englishmen dubbed the woman Topsy, after the enslaved girl in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s famous abolitionist novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/a2/bea28998-2b66-4b71-bd64-097f69f3f0d0/s3___eu-west-1_dlcs-storage_2_8_m0005572.jpeg)

Before long, these new occupants were joined by others, until a dozen or more crowded into the home. A pair of Andamanese were caught stealing crops from the colony’s gardens; they, too, were sent to the growing establishment as compulsory inmates, followed by their families. So noticeable were the comings and goings of these unclothed visitors that they were soon moved to a less conspicuous location on Ross Island, lest the innocent eyes of Englishwomen be further polluted.

In a report to Calcutta, Tytler congratulated himself on the “firmness, decision and kindness” with which the Andamanese guests were being treated. “They must see the superior comforts of civilization compared to their miserable savage condition,” he wrote. “Though not immediately apparent, we are in reality laying the foundation stone for people hitherto living in a perfectly barbarous state, replete with treachery, murder and every other savageness.” The colonel added, “Besides which, it is very desirable, even in a political point of view, keeping these people in our custody as hostages.”

He assured his superiors that while the Andaman Home was now fenced in with stout bamboo palings and guarded by armed Indian soldiers, its residents “otherwise enjoy full liberty.” Their orderly and submissive conduct, the colonel wrote, must surely “ripen into an intimacy and warm attachment, and be productive of incalculable blessings both to us and to this benighted outcast race.”

Corbyn’s progress reports were not so sanguine. Himself the product of a well-rounded English private education, he had resolved to treat his charges like schoolboys—which meant, in those days, that he would slap them smartly when they misbehaved. And as increasing numbers of Indigenous people were confined at the home, they misbehaved, in Corbyn’s eyes, more and more. Topsy would smear herself with body paint, then flop naked into an armchair, ruining the upholstery. One of the boys, rather than submitting cheerfully to instruction in his ABCs, seized a sewing needle and lunged as if to jab Corbyn’s eyes out.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4f/84/4f844d98-f868-4a79-8808-3adab2c846ce/ch4_4.jpg)

Worst of all, they showed none of the customary deference of Eton or Harrow boys: When he slapped them, they slapped back. Even when his pupils seemed better disposed, their behavior was often disconcerting, with the women sitting naked on the chaste young Englishman’s lap—albeit without any apparent libidinous motives—and affectionately fastening chunks of coral to his necktie.

At last, the clergyman hit upon what seemed an excellent idea for subduing the Andaman Home’s rambunctious inmates. He would impress upon them the manifold blessings—and the majestic power—of European civilization, in a way that he could not do in the rough frontier settlement at Port Blair: by taking a select group of them to the mainland. Reaching Calcutta, Corbyn’s eight travel companions—Tura, Topsy, a man nicknamed “Jacko” and five children—were received with even greater enthusiasm than “Jack Andaman,” a young Indigenous man kidnapped by the British on their first expedition to the islands, had been a few years earlier.

To demonstrate British military might, they were taken on tours of the city’s fortifications. To show off British technological prowess, they were shown the thundering steam-driven presses at the Calcutta Mint, then whisked aboard a railway car for a daylong excursion across 50 miles of countryside. To impress upon them the achievements of British scholarship, they were welcomed to a meeting of the venerable Asiatic Society, where they sat patiently while the learned members debated, at considerable length, whether it was advisable or even possible to civilize them.

They also became celebrities. Word spread quickly among the city’s native-born and white inhabitants that cannibal “monkey men” with long tails were staying in a house near the town hall. Within less than 24 hours, the building was thronged with Calcuttans clamoring to see them firsthand. Soon, the surrounding streets became impassable as curiosity seekers lined up all day for a glimpse of the picturesque visitors. To the Andamanese, it might have been startling to realize that the world contained so many people, that they and all their fellow islanders were so vastly outnumbered within the immense galaxy of the human species. Frustratingly for Corbyn, however, they remained apparently unawed by all the military fortifications, steam presses, railway cars and scholarly gentlemen.

Exposure to throngs of gawking civilians had other consequences. Topsy was the first of the eight Andamanese to fall sick. She eventually recovered a bit, but still, only half of the little group returned alive to Port Blair. Under circumstances only vaguely described in the official records, two of them drowned, one was “murdered” and one died “a natural death.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cf/e4/cfe48d1a-8def-4836-88ed-63eeb4ad3cae/sources_1.jpg)

Back at Ross Island, it became apparent that Corbyn’s project to subdue the island’s intractable native inhabitants by exposing them to the manifold blessings of civilization was having the opposite of its desired effect. On his return, he acknowledged, he had found their morale at its lowest ebb, and he confided in his journal—though not in his official report—that some of the women appeared to have suffered “unwanted advances” from the naval petty officer left in charge of the Andaman Home.

Soon, the home’s residents began escaping. Despite the stout fence, despite the armed guards, they slipped away by night. Most managed to swim the half mile to shore, some pushing their children on makeshift bamboo rafts. They fled by ones and twos, then en masse. One man even contrived somehow to get across while still in iron fetters.

After a few weeks, almost the only ones left were Tura and Topsy. She was still ailing, and he would not leave her behind. Then, one night, he got into an altercation with the guards and was hauled away in chains.

With her husband gone, the woman who had been called Topsy at last made her escape from Ross Island. She crept out of the home under cover of darkness, slipped into the phosphorescent water and started to swim. But her lingering illness had left her too weak to reach the opposite shore. Her body was found on the beach a few days later, half covered by the shifting sand.

Over the decades that followed, most of the Indigenous residents of the islands would be herded into similar “Andaman Homes,” forced to perform menial labor for the colonizers. They succumbed by the thousands to diseases that their enslavers had brought. Only a few tribes successfully resisted this fate. A few hundred Indigenous islanders now live scattered across the archipelago, in varying degrees of contact with the outside world. Only the Sentinelese still proudly defend their absolute independence.

Adapted from The Last Island: Discovery, Defiance and the Most Elusive Tribe on Earth by Adam Goodheart. Published by Godine. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/adam_goodheart.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/adam_goodheart.png)