In the yard of the stone elementary school with the tile roof in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, a town of just 2,700 people on a high plateau in south-central France, kids play and horse around like school kids everywhere. Except they sometimes chatter in different languages: They’re from Congo and Kosovo, Chechnya and Libya, Rwanda and South Sudan. “As soon as there’s a war anyplace, we find here some of the ones who got away,” says Perrine Barriol, an effusive, bespectacled Frenchwoman who volunteers with a refugee aid organization. “For us in Chambon, there’s a richness in that.”

More than 3,200 feet in elevation, the “Montagne,” as this part of the Haute-Loire region is called, first became a refuge in the 16th century, when residents who converted to Protestantism had to escape Catholic persecution. In 1902, a railroad connected the isolated area to industrial cities on the plain. Soon Protestants from Lyon journeyed there to drink in the word of the Lord and families afflicted by the coal mines of Saint-Étienne went to breathe the clean mountain air.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/e7/99e7a48b-a5c9-4104-a283-bd0b8abe7afe/julaug2018_j01_photoperkins.jpg)

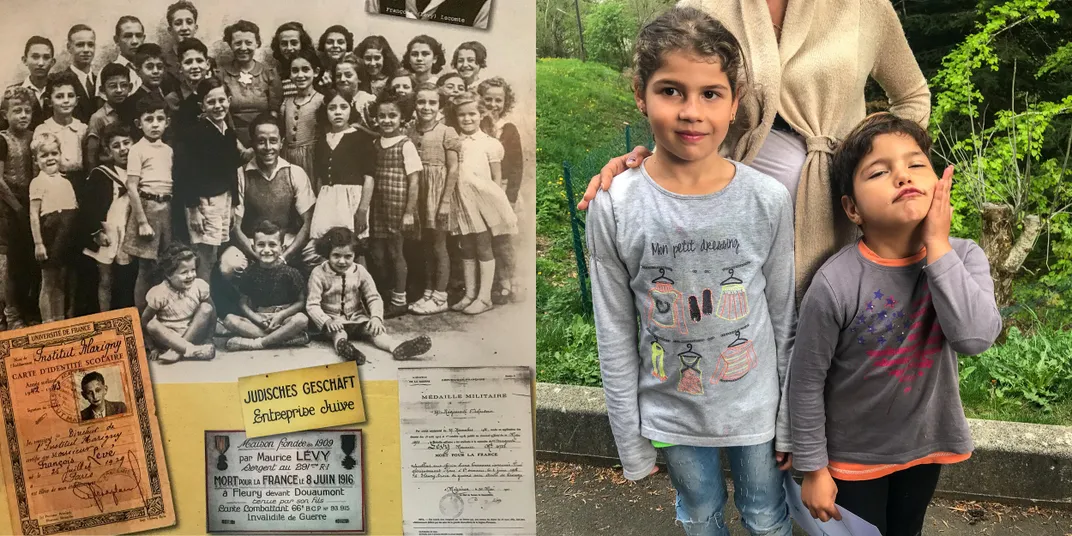

Thus Chambon-sur-Lignon, linked to Protestant aid networks in the United States and Switzerland, was ready for the victims of fascism. First came refugees from the Spanish Civil War, then the Jews, especially children, in World War II. When the Nazis took over in 1942, the practice of taking in refugees—legal before then—went underground. Residents also helped refugees escape to (neutral) Switzerland. In all, people in and around Chambon saved the lives of some 3,200 Jews. Local archives have not yielded one instance of neighbor denouncing neighbor—a solidarity known as le miracle de silence. In 1990, the State of Israel designated the plateau communities as “Righteous Among the Nations” for their role during the Holocaust, a supreme honor usually bestowed on an individual and given to just one other collectivity, a town in the Netherlands.

A Good Place to Hide: How One French Community Saved Thousands of Lives in World War II

The untold story of an isolated French community that banded together to offer sanctuary and shelter to over 3,500 Jews in the throes of World War II

The tradition of opening their homes to displaced people continues today. In the village of Le Mazet-Saint-Voy, Marianne Mermet-Bouvier looks after Ahmed, his wife, Ibtesam, and their two small boys, Mohamed-Noor, 5, and Abdurahman, 3. The family arrived here last winter and live for now in a small apartment owned by Mermet-Bouvier. They lost two other children during the bombing of Aleppo, and then spent three years in a Turkish camp. That’s where the French government’s Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides found the family. But even with entry papers, somebody in France had to put them up. Their sponsors, not surprisingly, were here on the plateau. Ahmed and his wife, now six months pregnant, smile often, and the word that keeps coming up in Ahmed’s choppy French is “normal.” Despite the upheavals of culture and climate, Ahmed finds nothing strange about being here, which, after the hostility he and his children encountered in the Turkish camps, was a thrilling surprise. “Everybody here says bonjour to you,” Ahmed marvels.

Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to explain how easily ordinary people can slip into monstrosity. The Bulgarian-French philosopher Tzvetan Todorov advanced its lesser-known opposite: the banality of goodness, which is what you run into a lot around here. The locals are sometimes known as les taiseux—the taciturn ones—because they hate making a fuss about their kindness to needy outsiders. Still, their generosity is extraordinary at this moment in history, when much of the world (including parts of France) is in a fever about immigrants and refugees, erecting walls and laws and political parties to keep “others” out.

Hervé Routier sits on Chambon’s municipal council and also teaches French to young immigrant men, using the driving-test manual as his text. “It’s not a decision we reflect on, it’s always been spontaneous,” Routier said of giving assistance. “We just keep doing what we’re doing.”

Margaret Paxson, an anthropologist who lives in Washington, D.C., learned recently that she has family ties to Chambon and is writing a book about the region. “This story is about now,” says Paxson. “Not because we need to turn the people who live here into angels, but because we need to learn from them.”

Next to the old elementary school stands a modern structure: the Lieu de Mémoire, or Place of Memory. The little museum, opened in 2013, is dedicated to the role of Chambon and nearby villages in sheltering refugees, Jewish children in particular. Its holdings include photographs, archives and videotaped first-person accounts from villagers and individuals who were rescued.

Gérard Bollon, a historian and resident, takes pride in the view from the museum’s second floor, which looks out on the schoolyard. “You see our little kids rushing toward the kids who have arrived from elsewhere, kids who don’t speak a word of French, and take them by the hand. There it is! We’ve succeeded. That’s our lineage.”

Photography for this piece was facilitated by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0e/f7/0ef71f19-d4fc-44e8-be7d-78a5c2d85deb/julaug2018_j07_photoperkins.jpg)