The Children of Civil Rights Leaders Are Keeping Their Eyes on the Prize

The next generation is following in the footsteps of its forebears

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/ef/e3efe032-a09d-460d-b452-455b540a23b0/sep2016_f02_generations.jpg)

As a part of the September issue devoted to the grand opening of the Smithsonian's newest museum, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, our writers caught up with Bernice King, Ilyasah Shabazz, Cheryl Brown Henderson, Gina Belafonte, Ayanna Gregory and Ericka Suzanne, all children of prominent Civil Rights leaders of the 1960s and '70s. Here are their stories:

Bernice King

Martin Luther King Jr.’s message of peace might seem like a distant dream after this summer of violence—which is why his daughter, Bernice King, believes it’s more urgent than ever

“My heart aches right now, because the next generation deserves a lot better.”

Bernice King, the youngest child of Martin Luther King Jr., was sitting on the top floor of the King Center, the Atlanta educational nonprofit she has run since 2013, staring down at her smartphone. The screen pulsed with the news of the week: Protests in Baton Rouge. Protests in New York. Five cops assassinated in Dallas. A Minnesota man named Philando Castile fatally shot in his car by a police officer while his fiancée streamed the encounter on Facebook Live.

King says she watched the video, all the more devastating because of the woman’s young daughter in the back seat: “And she goes, ‘Mommy, I’m here with you,’ or something like that, and watching that, I just broke down in tears. All I could think about was being at my father’s funeral, sitting on my mother’s lap and looking up at her, and being so puzzled, so troubled, so perplexed and confused, and, phew, I will tell you: It brought me back.”

Five years old at the time of her father’s death, King has spent most of her life grappling with his oversized legacy. As a young woman she dodged the ministry, stumbled through law school—at one point, she says, she contemplated suicide—and clerked for a judge in Atlanta. “I wanted to feel free to be Bernice, to find myself amid all the trauma, and not to get lost in all that Kingness,” she recalls. “But the whole time, I was staying involved with the King Center”—which her mother, the late Coretta Scott King, founded in 1968—“attending the conferences on my father’s nonviolent philosophy, and eventually I decided that’s where my heart was.”

Not that it’s been easy. In 2005, then a member of the King Center’s board, she was criticized for her use of center grounds for a march against same-sex marriage legislation. And in 2006, she attempted, unsuccessfully, to block the transfer of nearby historic buildings to the National Park Service, only to fall into a series of spats with her two brothers. (Her sister died in 2007.)

Now King finds herself at the helm of the King Center—with its mission to spread the gospel of nonviolent protest—at perhaps the most fraught moment for American race relations in a generation. “I have a lot of sadness about what’s happening in our nation,” she says. “It just seems like we’ve become so polarized. So focused on violence.” But she takes solace in the work the center does: the educational seminars the organization sponsors in the field, in places like Ferguson, Missouri; the ongoing stewardship of the vast King archives.

“I see a major part of my job as keeping Daddy’s words and philosophy alive,” King says. “Because I think if we could get back to that philosophy, to listening and not being afraid of exploring the information on the other side, and finding ways to make connections without compromising personal principles—well, we’d move things forward.” Then she offered a piece of wisdom from a different parent. “It’s like my mother said: ‘Struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won, you earn it and win it in every generation.’ That’s how I feel today, you know? The fight isn’t over.” — Matthew Shaer

Ilyasah Shabazz

Her father advocated using either “the ballot or the bullet.” But Ilyasah Shabazz wants to show another side of Malcolm X

Ilyasah Shabazz was just 2 years old and sitting in the audience with her pregnant mother and three sisters when her father was assassinated onstage at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City in 1965. Malcolm X, the magnetic and polarizing spokesman for the Nation of Islam, had broken with the black nationalist group, and three Nation members were convicted of the killing. The “apostle of violence as a solution to the American Negro’s problems...was murdered today,” the New York Herald Tribune reported, nodding at Malcolm X’s exhortation to use “any means necessary” to achieve equality. In his eulogy, the actor Ossie Davis expressed a more nuanced view, lamenting the loss of “our living, black manhood.”

As debate raged over Malcolm X’s impact, Ilyasah Shabazz and her five sisters were insulated from the firestorm by their mother, Betty Shabazz, who moved the family from Queens to a big house on a tree-lined street in Mount Vernon, New York. “I think my mother focused on making sure that we were whole,” Shabazz says one morning in her apartment not far from her childhood home as she recalls a suburban upbringing of private schools and music lessons. Betty herself exemplified a quiet community activism, founding a program that helped teenage mothers continue their education.

Though Malcolm’s coats hung in the hall closet and his papers were in the study, it wasn’t until Shabazz went away to college and took a course on her father—reading his speeches and his autobiography—that his work came into focus. “My father was made to be this angry, violent, radical person. And so I always say, look at the social climate....He was responding to the injustice.” Her favorite speech of his is the 1964 Oxford Union debate, where he argued that when “a human being is exercising extremism, in defense of liberty for human beings, it’s no vice.”

Like her father, Shabazz advocates for civil rights, but, like her mother, a professor before her death in 1997, she stresses education. “When young people are in pain, they don’t say, ‘I’m in pain. Let me go get a good education,’” she says. A decade ago, she founded a mentor program that introduces teens to artists, politicians and educators who overcame hardship. Last year, she began teaching a class at John Jay College of Criminal Justice on race, class and gender in the prison system.

She has also written three books about her father, including one for children, and co-edited a volume of his writings. While her books gently echo his appeals for education and empowerment, she boldly defends his legacy. When we learn African-American history, she says, “it’s either Malcolm or Martin, the bad guy and the good guy. But if you look at our society and our history, we know about Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, and we’re taught to celebrate both of them.” — Thomas Stackpole

Cheryl Brown Henderson

Her family’s name is synonymous with the case that ended segregation in schools. More than 60 years later, Cheryl Brown Henderson says we still have a lot to learn

In 1970, when Cheryl Brown earned a spot on the all-white cheerleading squad at Baker University in Kansas, someone set fire to her dormitory-room door. “People don’t like change and power concedes nothing without a fight,” she says.

She would know. Few families in U.S. history are more closely tied to the fight over desegregation. She was just 3 in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education that the nation’s segregated schools were unconstitutional.

Her father, Oliver Brown, a pastor in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, had joined the lawsuit on behalf of Cheryl’s sister, Linda, then 8, who was barred from attending the white elementary school in their Topeka neighborhood. The case, organized by the NAACP, involved more than 200 plaintiffs from three other states and the District of Columbia and, famously, was argued by Thurgood Marshall, who went on to become the country’s first African-American Supreme Court justice. Cheryl Brown says her father was hesitant to join the lawsuit, but her mother convinced him so their children and others “would have access to any public schools, not simply being assigned based on race.”

Cheryl Brown (pictured above at left with her mother, Leola Brown Montgomery, center, and sister Terry Brown Tyler), whose married name is Henderson, went on to work as a teacher and guidance counselor for Topeka Public Schools and serve as a consultant for the Kansas Board of Education. (Her sister Linda worked as a Head Start teacher and a music instructor. Her father died in 1961.) In 1988 Brown Henderson co-founded the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to inform the public about the historic lawsuit.

By providing scholarships for minority students to pursue careers in education, Brown Henderson is trying to break down another educational barrier—the achievement gap. Overall, black and Latino students have lower high-school graduation rates and lower standardized test scores than white students. She acknowledges the need for sweeping policy reform but also believes that educators of color must play a significant role in the development of minority students. “We have a lot of work to do,” Brown Henderson says. “We can’t keep losing generations.” — Katie Nodjimbadem

Gina Belafonte

The renowned singer Harry Belafonte rallied famous actors and musicians to the civil rights movement. His youngest child, Gina Belafonte, activates a new generation of tech-savvy celebrities

Last year, Sankofa, the non-profit organization founded by Harry Belafonte and his youngest child, Gina, got a call from Usher’s manager: The singer needed help. “He was angry about people getting murdered by police officers,” Gina says. “So we sat down with them and strategized how they could bring their message to the masses.” The result was “Chains,” a video that forced viewers to stare into the eyes of unarmed people who were killed by police. If the camera detected a wandering gaze, the words “Don’t Look Away” appeared and the video stopped playing.

The short film epitomizes what the Belafontes had in mind when they started Sankofa in 2014: It bridges the worlds of entertainment and advocacy. The New York-based group—whose members include actors, professors, lawyers and community organizers—is a digital-era continuation of Harry Belafonte’s longtime grassroots organizing.

It was in 1953 that Belafonte had his first meeting with Martin Luther King Jr. Both men were then in their mid-20s, and the civil rights leader wanted the singer to join him in launching his movement. Their 45-minute appointment stretched to four hours, and Belafonte became one of King’s most trusted allies. “I respond as often as possible, and as totally as possible, to Dr. King,” Belafonte told TV host Merv Griffin in 1967. “And his needs and emergencies are many.”

It was a risky time to be so deeply involved in politics. The McCarthy hearings were silencing some of Hollywood’s most impassioned voices. Still, King and Belafonte were able to recruit celebrities such as Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman, Sammy Davis Jr., Charlton Heston, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan to attend the 1963 March on Washington.

Gina, who was born in 1961, remembers many of these artists passing through her family’s living room. “It was an open-door policy,” says Gina, now an actress herself, with credits including the 1988 film Bright Lights, Big City and the soap opera All My Children. “I was sitting on their hips, on their laps, on the chairs next to them, and then, finally, stuffing envelopes and licking stamps, helping out however I could.”

As an adult, Gina devoted herself to the issue that was on King’s mind just before he died. “He was about to launch the Poor People’s Campaign,” she says. For years, Gina was involved in reforming the prison system and working with former gang members.

Now, at Sankofa, Gina is carrying on her father’s work with celebrities. In October, the organization will host a two-day social justice festival in Atlanta featuring singers such as Estelle, Dave Matthews, and Carlos Santana and activists such as Cornel West. Harry Belafonte, nearing 90, remains involved in Sankofa’s meetings and planning. As he put it in Sing Your Song, a 2011 documentary about him that Gina lead-produced, “I tried to envision playing out the rest of my life almost exclusively devoted to reflection. But there’s just too much in the world to be done.” — Jennie Rothenberg Gritz

Ayanna Gregory

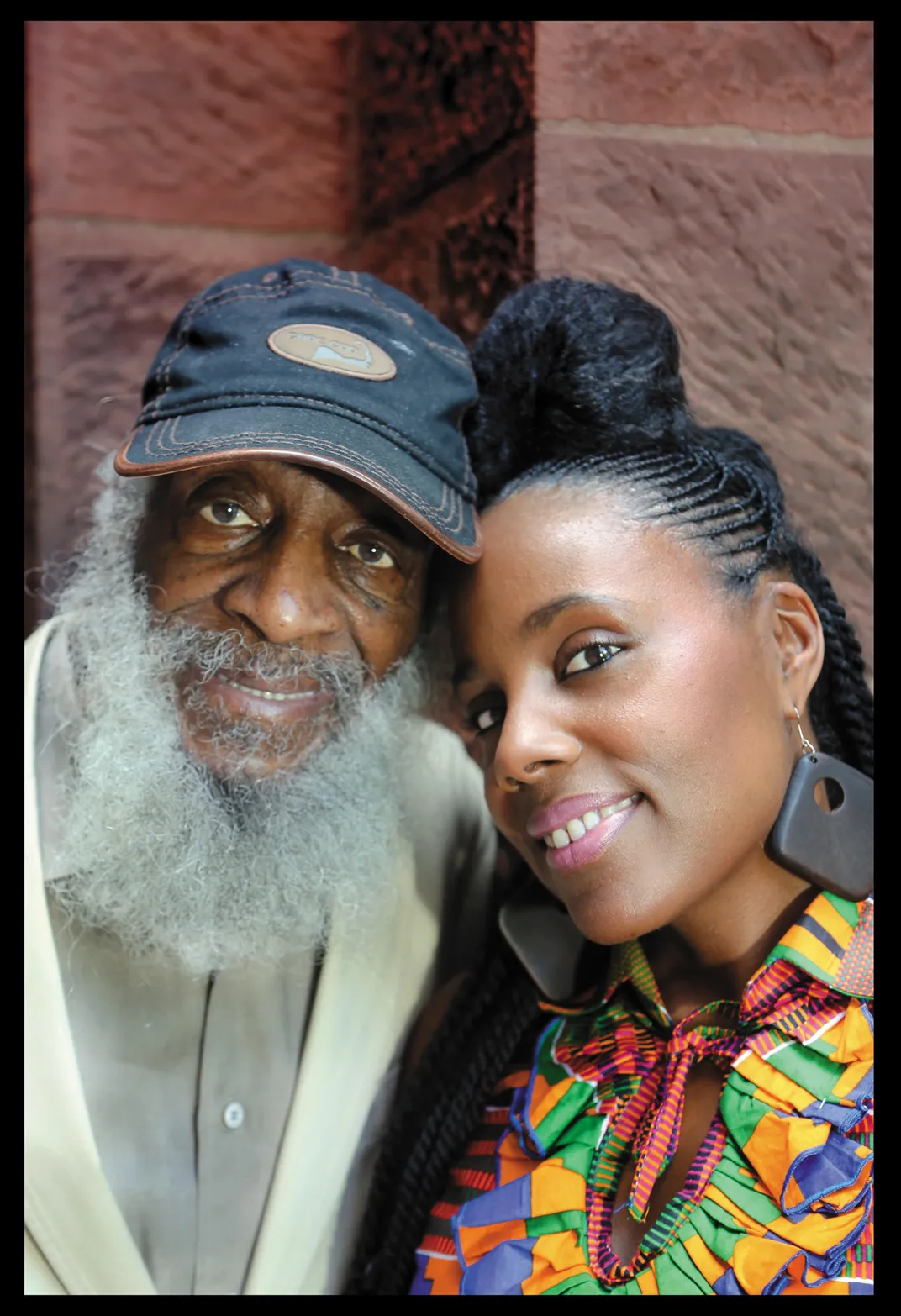

Dick Gregory used humor to bring Americans to action, but his daughter Ayanna takes a more dramatic turn on the stage

In the early 1960s, when Dick Gregory was working at the Playboy Club in Chicago, he used to tell a joke about a restaurant that refused to serve “colored people.” The punch line: “That’s all right, I don’t eat colored people. Bring me fried chicken.”

Gregory, who started performing in the 1940s, was one of the first mainstream comedians to boldly highlight the absurdity of segregation in his routine. But at civil rights rallies, he was all business. “When I went down to Selma, I wasn’t going there to entertain no goddamn people,” he says now. “I went down to go to jail. I was ready to die.”What do comedy and activism have in common? Timing, says Ayanna Gregory, the second youngest of Gregory’s ten children. “In comedy, if you don’t have the right rhythm, folks won’t catch the joke,” she says. “He had that rhythm in other parts of his life, too. It’s all about paying attention and knowing what you need to do, in that moment.”

It took Ayanna a while to find her own rhythm. After starting out as a schoolteacher, she began performing for young audiences. In a musical program called "I Dream a World," she encourages kids to imagine progress. “When you ask kids what they want, they tell you what they don’t want: ‘I want a world with no drugs and no violence.’ I ask, ‘What about the world you do want? What does that look like?’”

Last year, Ayanna debuted a one-woman dramatic tribute to her father, Daughter of the Struggle, which recounts that her older siblings were taken away in police wagons and faced down mobs in Mississippi. “Dad never told any of us what to do with our lives,” Ayanna said. “But we grew up with his example—seeing someone who isn’t willing to kill for his beliefs but is willing to die for them. That made all the difference.” — Jennie Rothenberg Gritz

Ericka Suzanne

She grew up a Black Panther and emerged from the chaos of the 70s with a newfound respect for the value of community organizing

On her iPhone, Ericka Suzanne keeps a copy of a class photo from the Oakland Community School, an academy founded by the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s. Suzanne herself is in the front row, next to Bobby Seale’s son, a composed and serious expression on her face, a black beret crooked on her head. She is Panther royalty: The only daughter of Elaine Brown, the first female leader of the party.

Three years after the photo was taken, in 1977, Brown, increasingly fearful of the misogynistic strains growing within the group, spirited her daughter away to Los Angeles, where Suzanne would spent the remainder of her childhood. “It was difficult, because you’ve been told your whole life to prepare for a revolution,” Suzanne, now 47, recalls. “But what if the revolution never comes? What exactly do you do with your life?”

She made the decision to take what saw as the best parts of the Panther movement—giving back to the community, fighting for equality—and applying it to her own life. She moved to Ohio, and found a job at the Harriet Tubman Museum, and then at the nearby Hattie Larlham Center for Children with Disabilities. There, she spent her days helping to guide students through gardening, painting and work training programs. Now in Atlanta, Suzanne hopes to open a similar program on the East Coast.

She says she is often approached by strangers who tell her that they grew up in the Bay Area, and didn’t starve because of the Black Panthers breakfast programs, or that they had clothing and books and shoes because of the Black Panthers.

“That makes me proud,” she says. “And also sad, because I’m not sure that the energy and urgency of that moment, and that movement, can ever be replicated.” — Matthew Shaer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)