The Children of Pearl Harbor

Military personnel weren’t the only people attacked on December 7, 1941

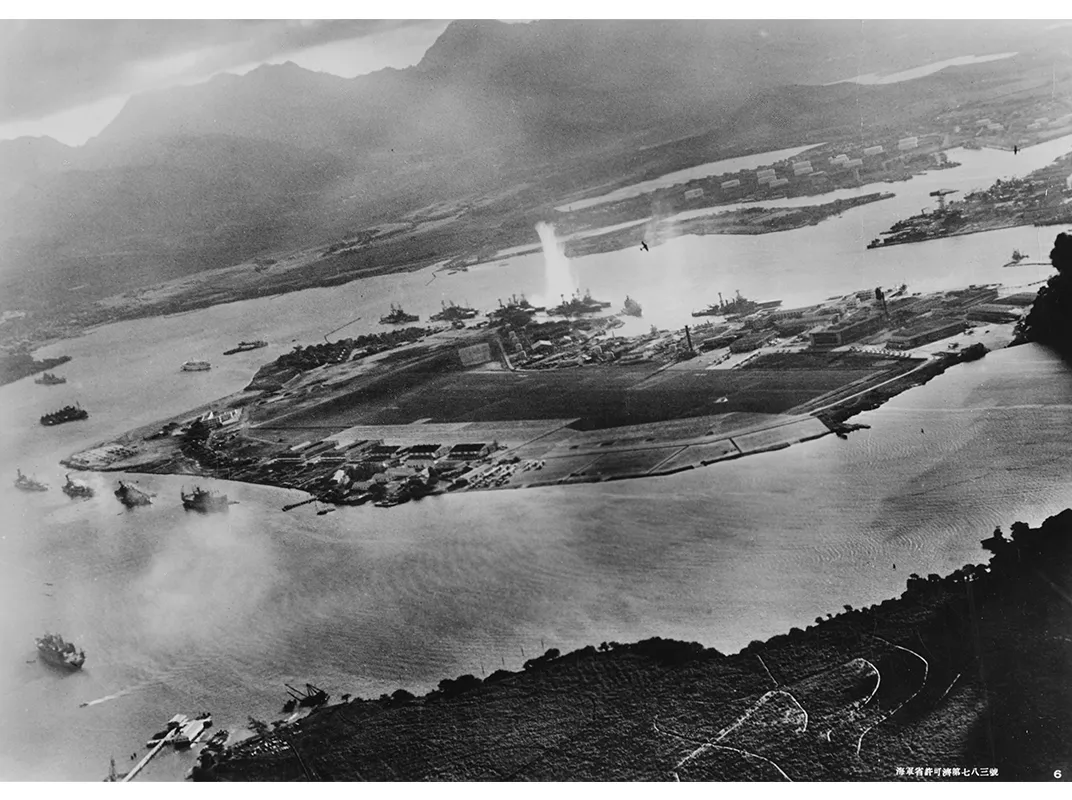

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/02/14026f9d-51b9-46f7-8854-05f1676c4635/attack_on_pearl_harbor.jpg)

Eighty years ago at dawn, more than 150 ships and service craft of the United States’ Pacific fleet lay at anchor, alongside piers, or in dry dock in Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. By late morning, the surprise Japanese air and mini-submarine attack had left 19 vessels sunk or badly damaged and destroyed hundreds of airplanes.

Death was everywhere. The toll that day among military personnel is widely known. Of the 2,335 servicemen killed in the attack, nearly half died on the USS Arizona when a Japanese bomb blew up the battleship’s forward gunpowder magazine, ripping the ship apart. Hundreds also died aboard other stricken naval vessels and in bombing and strafing attacks at nearby airfields.

But few people realize that 68 civilians were also killed in the attack. Japanese fighters strafed and bombed a small number. Most, however, died in friendly fire when shells from Coast Guard ships and anti-aircraft batteries on shore aimed at the Japanese fell into Honolulu and elsewhere on the island. Eleven of the dead were children ages 16 and younger.

The Hirasaki family suffered some of the worst losses that terrible morning. The Japanese-American mother, father and their three children. ages 2, 3 and 8, together with a 14-year-old cousin, sheltered in the family’s downtown Honolulu restaurant. An errant shell struck the building. Only the mother survived. Seven other patrons taking cover there also died in the blast.

Countless children throughout Oahu also witnessed the attack, perhaps none more closely than 8-year-old Charlotte Coe. I got to know Charlotte four years ago when I interviewed her for a book I wrote about the period before the Pearl Harbor attack. Charlotte, whose married name was Lemann, would die of cancer two years later, but when we spoke she recounted her experiences that fateful morning as if they were a film that had been running continuously in her mind ever since.

Charlotte lived with her parents and five-year-old brother, Chuckie, in one of the 19 tidy bungalows lining a loop road in an area known as Nob Hill, on the northern end of Ford Island. That island served as home to a naval air station in the middle of Pearl Harbor. Their father, Charles F. Coe, was third in command there. The Nob Hill mothers watched over their 40 or so young “Navy juniors” while their fathers went off to the air station’s hangars, operations buildings and aircraft operating from the island. The Coe family’s house looked out on the harbor’s South Channel and the double row of moorings known as Battleship Row.

The air station and Pacific fleet defined the children's days and nights. Charlotte, Chuckie and their friends often ran out the nearby dock to meet officers disembarking from the ships. Lying in bed at night, Charlotte could hear voices from the movies being shown to sailors on board. Until the Pearl Harbor attack, she recalled that she and the other children lived “free as birds” on Ford Island, taking a daily boat to school on the Oahu mainland. At home, Pearl Harbor’s lush tropical shoreline served as their playground.

But Ford Island was something else: a target. The eight battleships moored along Battleship Row were the Japanese attackers’ primary objective when they flew toward Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941.

The first explosion at 7:48 that morning woke Charlotte from a sound sleep. “Get up!" she remembered her father shouting. "The war’s started.” The family and the men, women and children from the other houses raced for shelter in a former artillery emplacement dug beneath a neighboring house. As they ran, a khaki-colored airplane with red circles under its wings zoomed past so low that Charlotte saw the pilot’s face.

Before that day, the children had often played inside the dimly lit, concrete-lined bunker they called “the dungeon.” The Nob Hill families practiced how they would hide there in case of an air raid. Once inside, Chuckie could not resist the noise, explosions and flames and ventured outside. This time Japanese bullets zinged around him before Charles hauled him back.

As Charles returned home to get dressed before helping organize a defense, a massive explosive knocked him to the ground. The Arizona’s detonation rocked the walls and floors inside the children’s dungeon shelter. Charlotte shook her fist. “Those dirty Germans!” she recalled saying. “Hush, ChaCha," said her mother quietly. "It’s the Japanese.”

Before long, survivors from the blasted and battered battleships began filtering ashore and into the bunker. Mostly young men, they were wide-eyed, scared, coated in oil. They were the lucky ones. Others had been hit by the blasts and flying debris, strafed or horribly burned. Seventy years later, Charlotte still vividly remembered the burnt flesh that hung in charred ribbons from some of the men. Hidden in the bunker, she saw men succumb to their wounds.

When a naked, shivering sailor propped himself against a wall next to her, Charlotte remembered unzipping her favorite blue quilted bathrobe and handing it to him. He wrapped his bare body in it and thanked her.

In later years, Charlotte learned that her mother had taken a soldier aside to tell him to save three bullets in his pistol. She had heard about the atrocities the Japanese had inflicted on Chinese women and children and expected that the Japanese would soon invade Oahu. “When I am sure that my children are dead, then you will shoot me,” she commanded.

As Charlotte exited her former playhouse at last, she looked out on a vision of hell. Ships were in flames, submerged and capsized; fires burned everywhere, the air thick with acrid black smoke; bodies barely recognizable as human floated in the water or lay on the grassy shore where she used to play.

When Charlotte Coe Lemann recounted those few hours, the decades disappeared in an instant. Even as the attack was unfolding, she said, she knew that “A lot of those men I’d seen coming along the dock from ships were never coming again.”