After the Civil War, African-American Veterans Created a Home of Their Own: Unionville

One-hundred-fifty years later, the Maryland town remains a bastion of resilience and a front line in the battle over Confederate monuments

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/83/28836df2-526c-48da-ad04-5978fa6fe92c/sep2017_e04_unionville-wr.jpg)

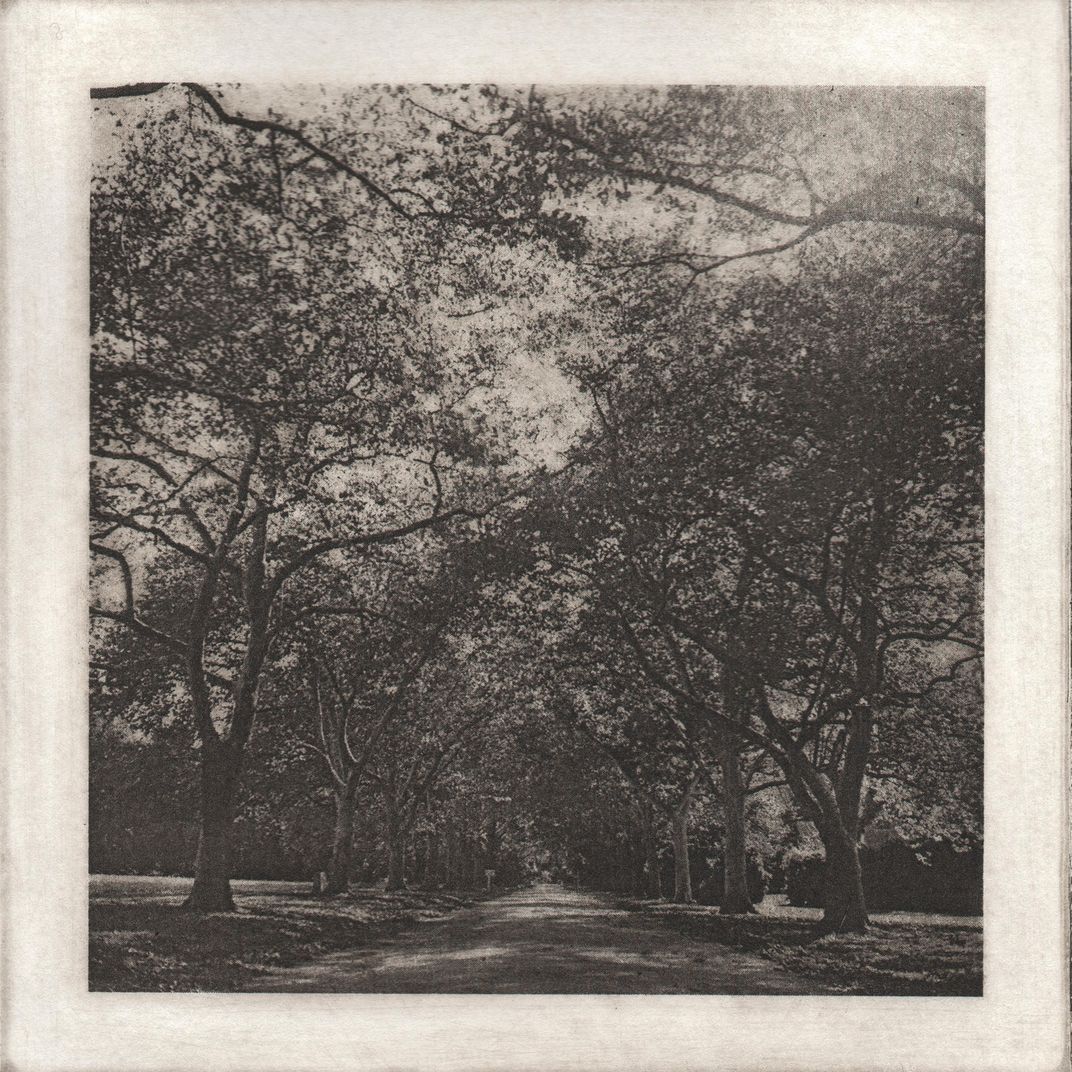

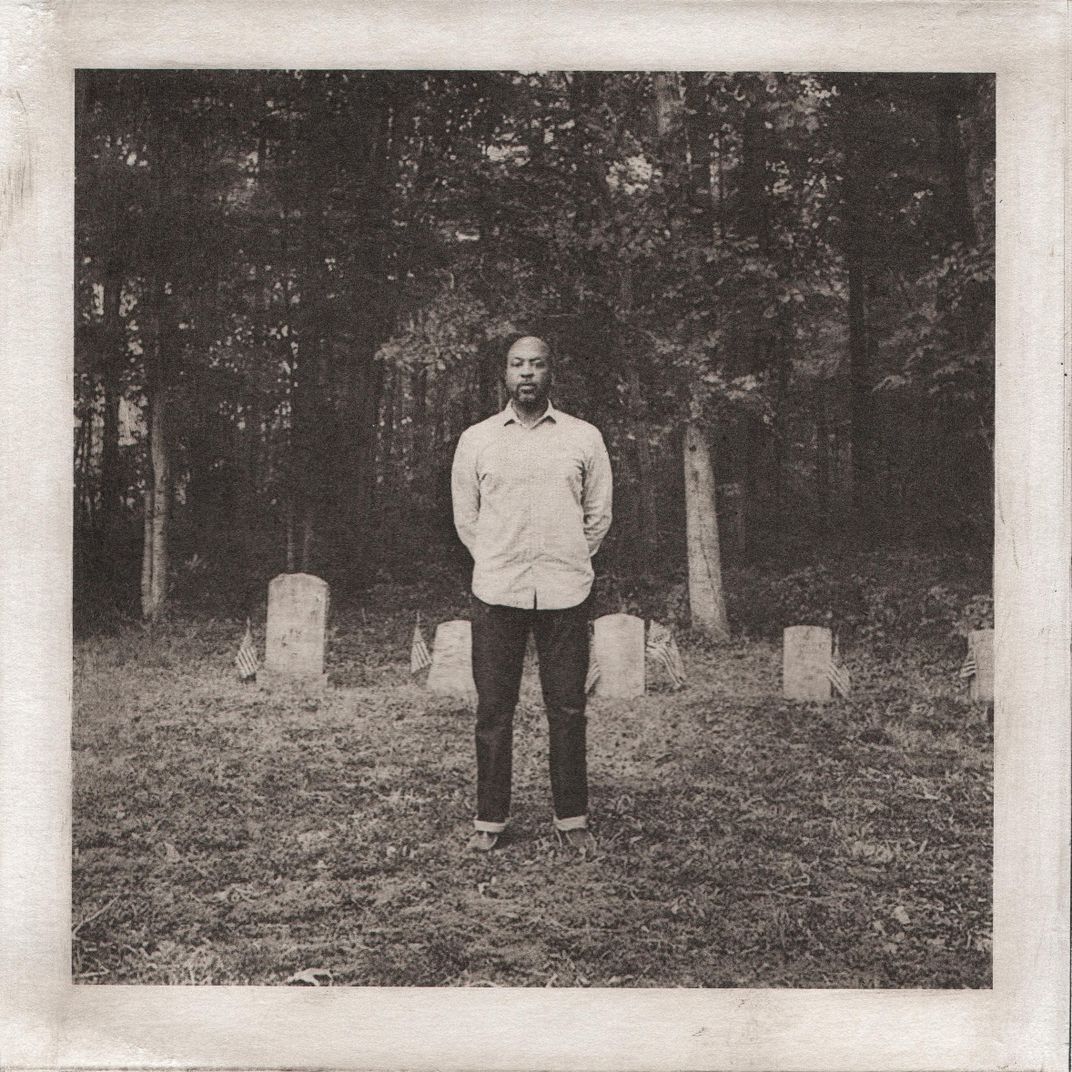

After the Civil War, 18 veterans of the United States Colored Troops returned to Talbot County, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where their families had toiled for generations. But this time, they had a chance to create something their ancestors had been denied: a village of their own, where everyone was free.

It is believed to be the only village in the United States founded by formerly enslaved soldiers. And now, as it celebrates its 150th anniversary, it stands as a powerful symbol of resilience.

The founders named it Unionville—a daring statement in that time and at that place. While Maryland had remained in the United States during the war, most of the landed gentry of Talbot County had been fiercely secessionist. Eighty-four sons of Talbot fought for the Confederacy; one of them, Franklin Buchanan, served as an admiral in the Confederate navy. The presence, after the war, of a free, black settlement, named for the hated Union, made a dramatic claim to equality and liberty.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

The passionate man labeled as the “most influential African American of the nineteenth century.” This is his voice. This is his story.

It was the persistence of questions about race and justice in America that drew the photojournalist Gabriella Demczuk to Unionville in the summer of 2015. After documenting the killings of several unarmed black men around the country, she noticed that much of “the coverage we were seeing only perpetuated the negative stereotypes of black communities. I wanted to work on a story that celebrated black life.” Demczuk, who grew up around Baltimore, visited Talbot County as a young woman and heard about a history that her uncle, Bernard Demczuk, who was a George Washington University administrator and lecturer, was writing about Unionville. But only after the 2015 killing of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, she says, did she “finally pick up his book and learn about the town’s history.”

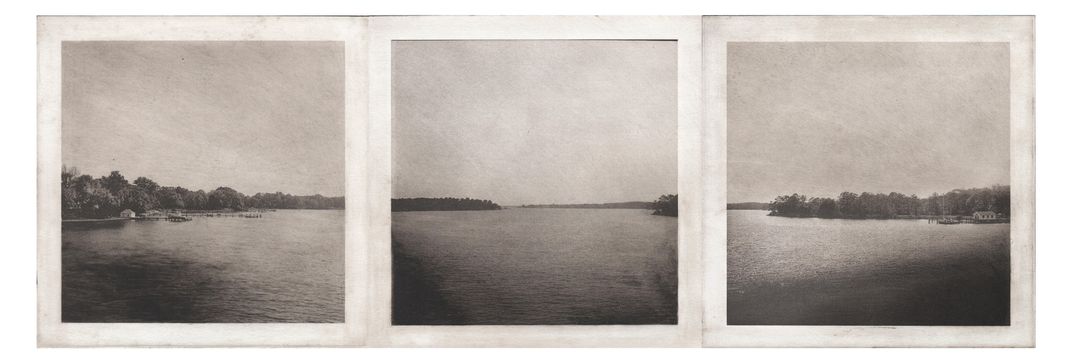

The establishment of Unionville defied more than 200 years of Talbot County history: For generations, slavery was “part and parcel of the land,” Bernard Demczuk writes in his history. From the time the county was founded, in the 1660s, it depended on enslaved labor, and its plantation economy made a handful of white families quite rich. The Eastern Shore’s terrain, laced with creeks and rivers leading to the Chesapeake Bay, made it easy to send out tobacco, grain and other crops—and to bring in enslaved workers.

But, as Bernard Demczuk told me recently, “The waterways that enslaved you could also free you.” Frederick Douglass (who once worked at the Wye House, a short walk from where Unionville now stands) and fellow abolitionists Henry Highland Garnet (from nearby Kent County) and Harriet Tubman (from Dorchester, one county south) all escaped enslavement and its astounding cruelty. Douglass, in his 1845 autobiography, describes an overseer whipping a laborer named Demby, then shooting him dead after he sought relief from his wounds by jumping into a creek.

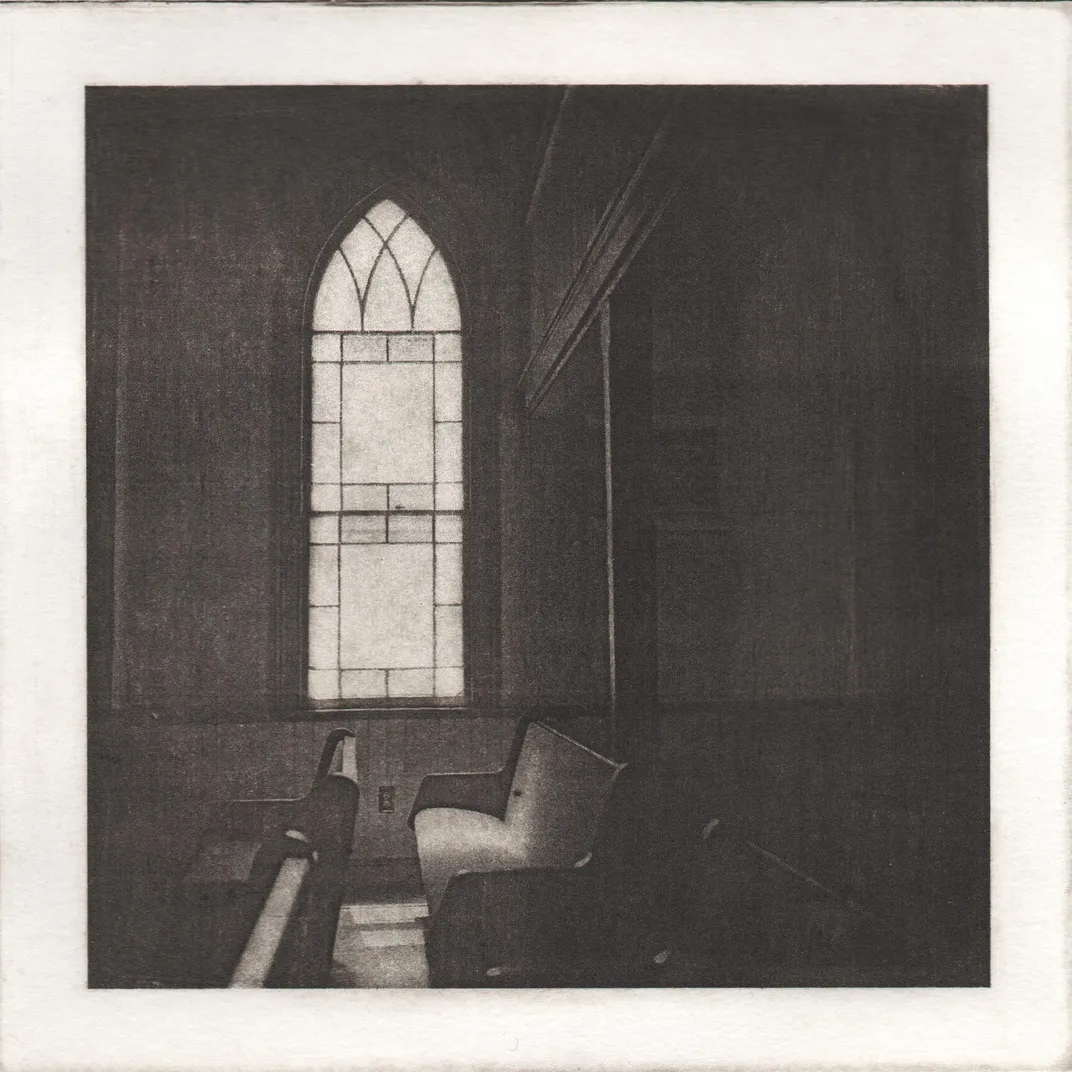

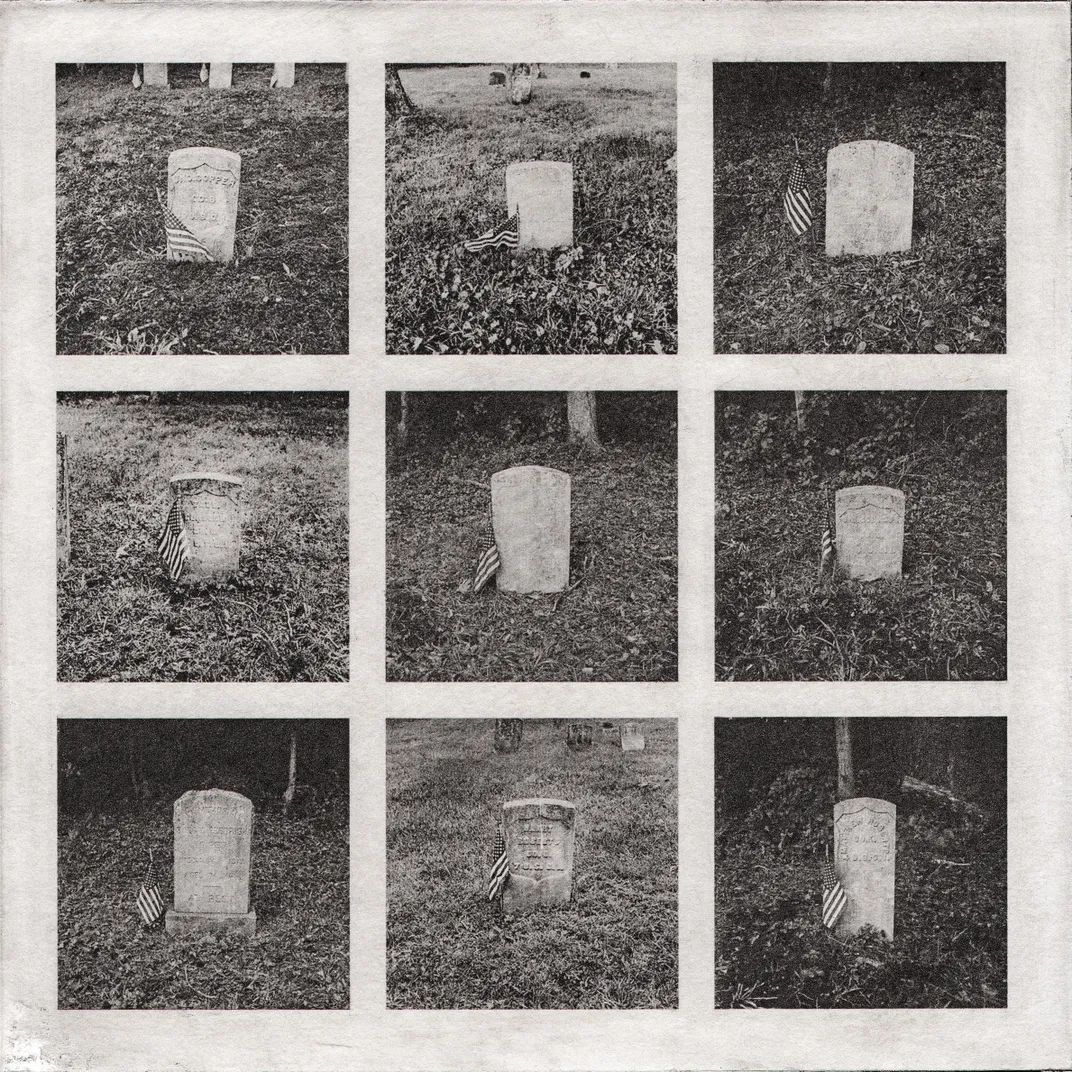

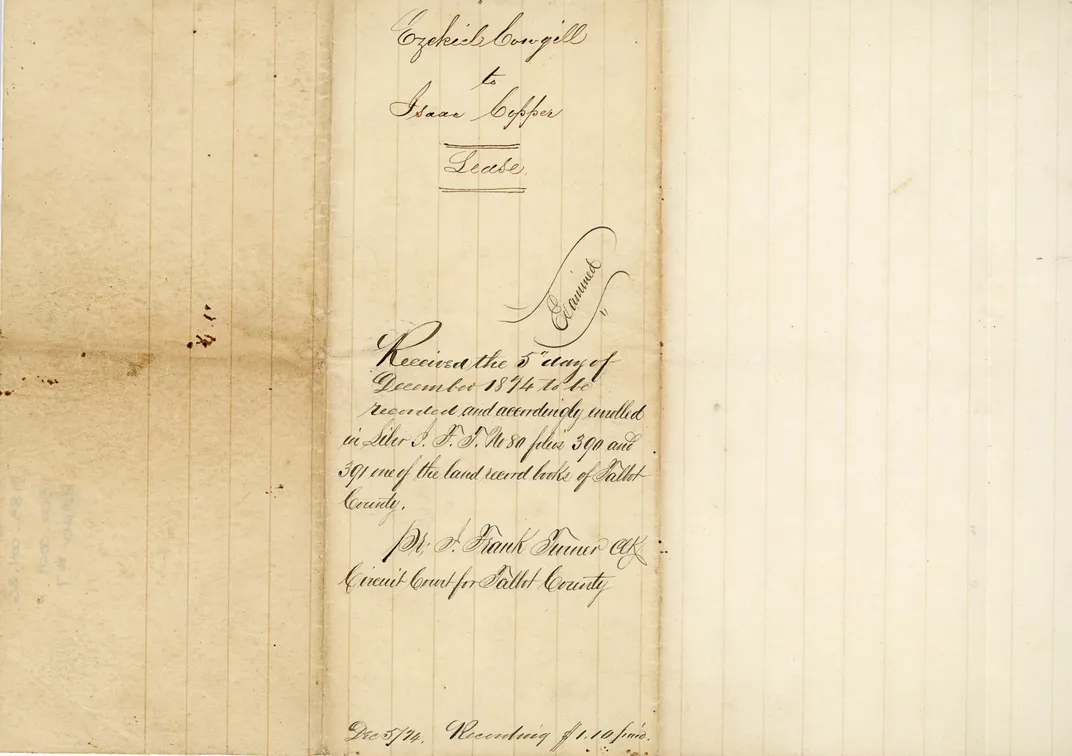

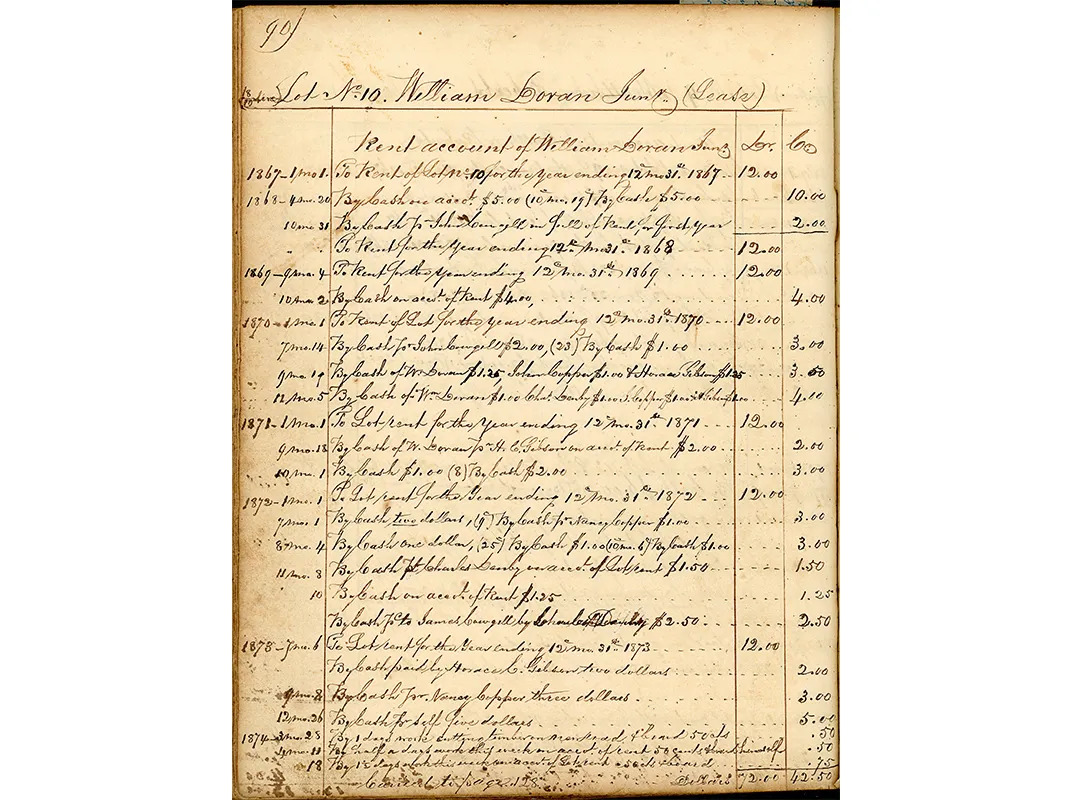

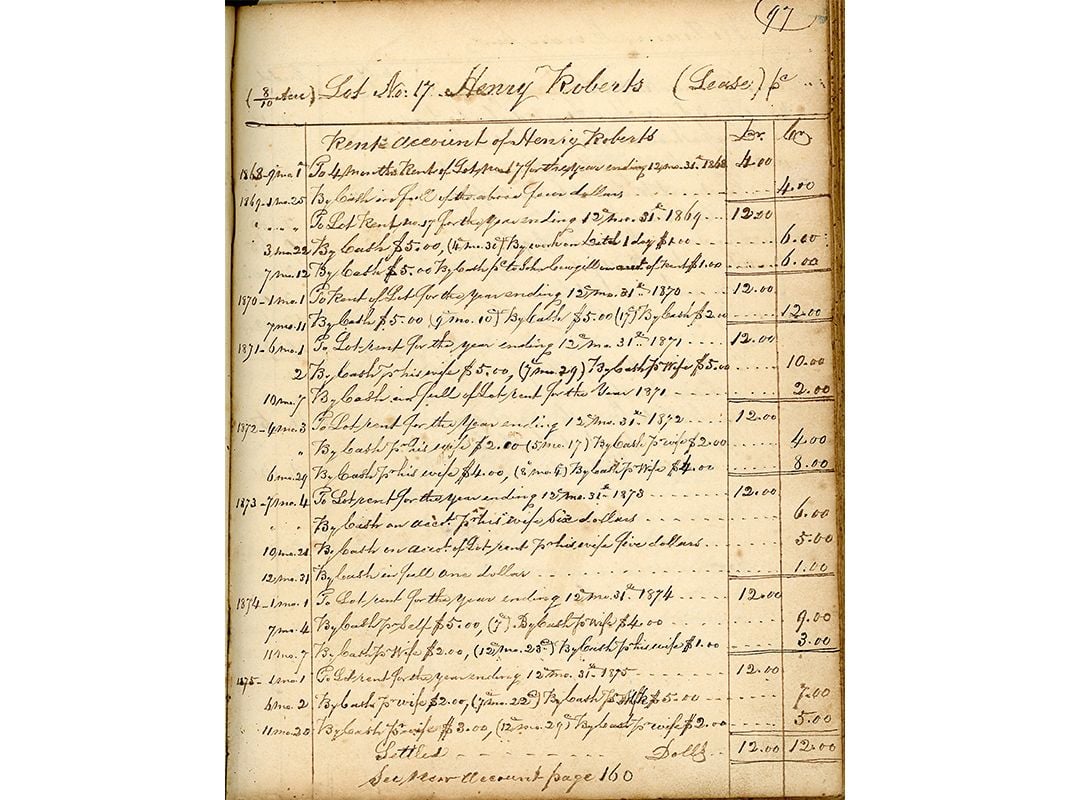

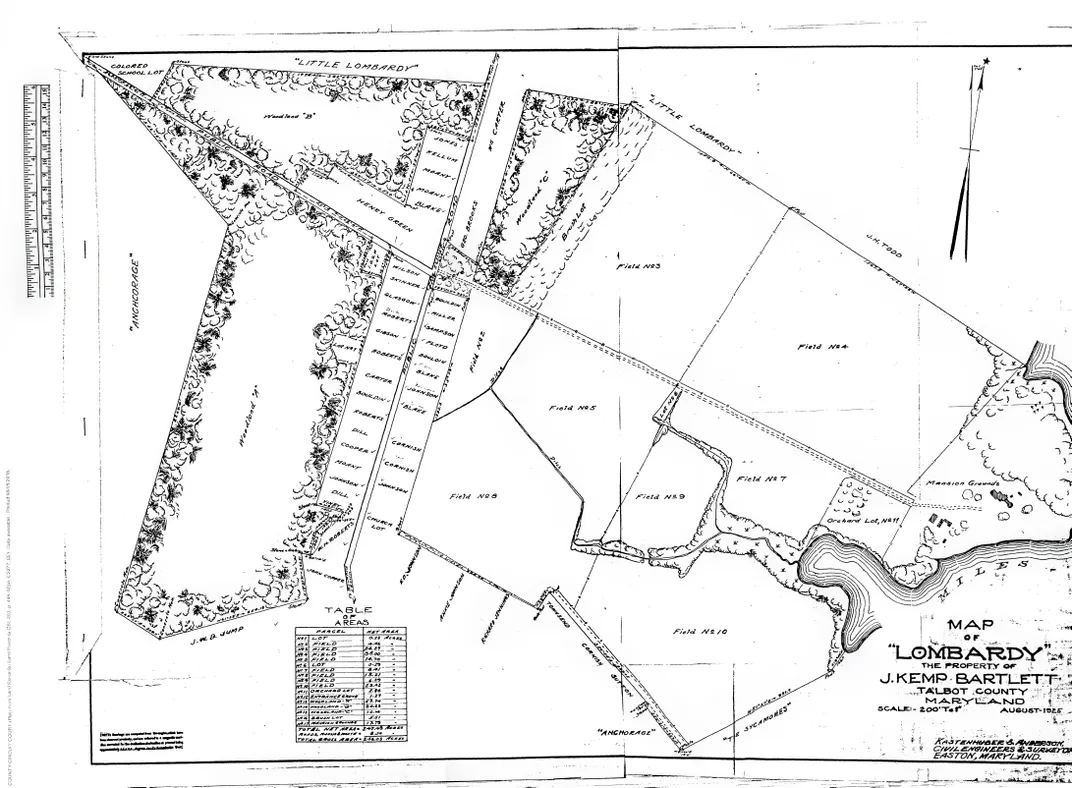

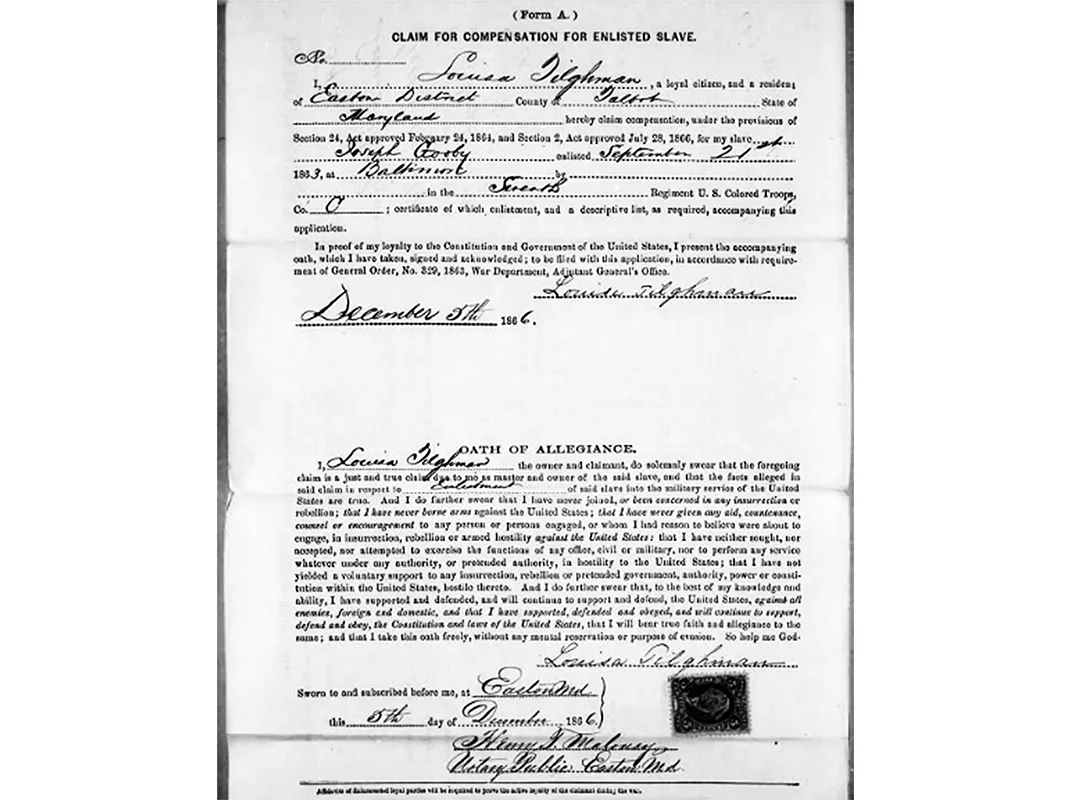

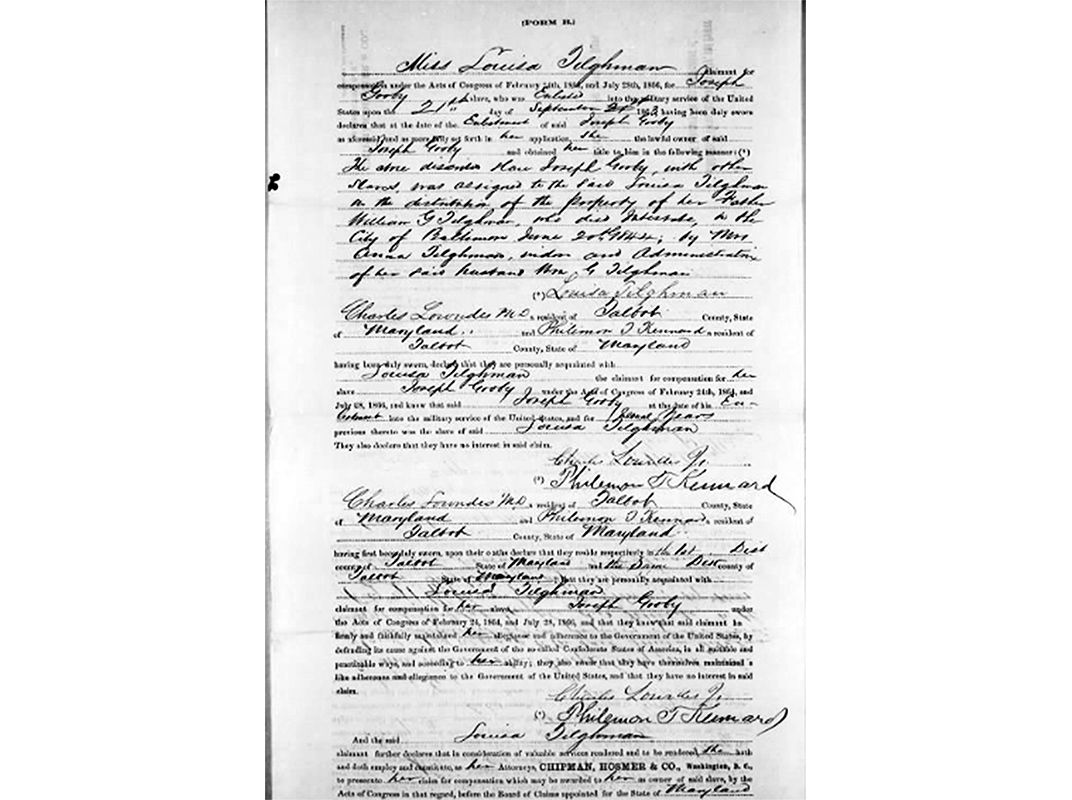

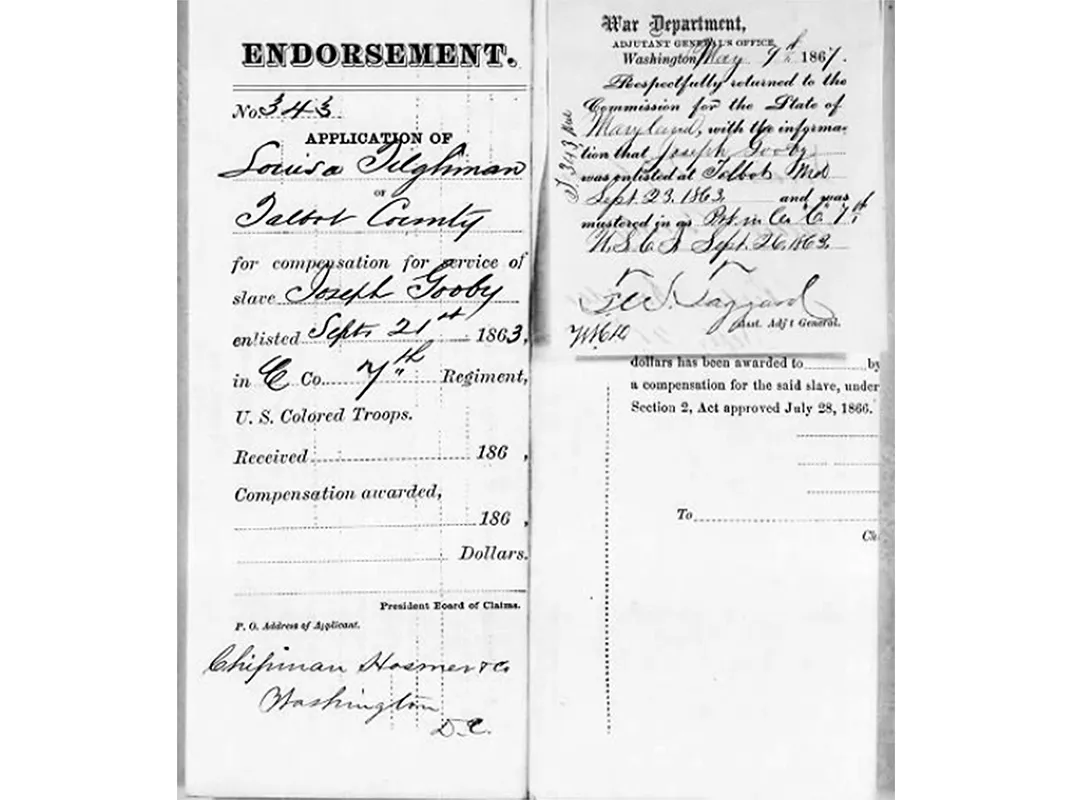

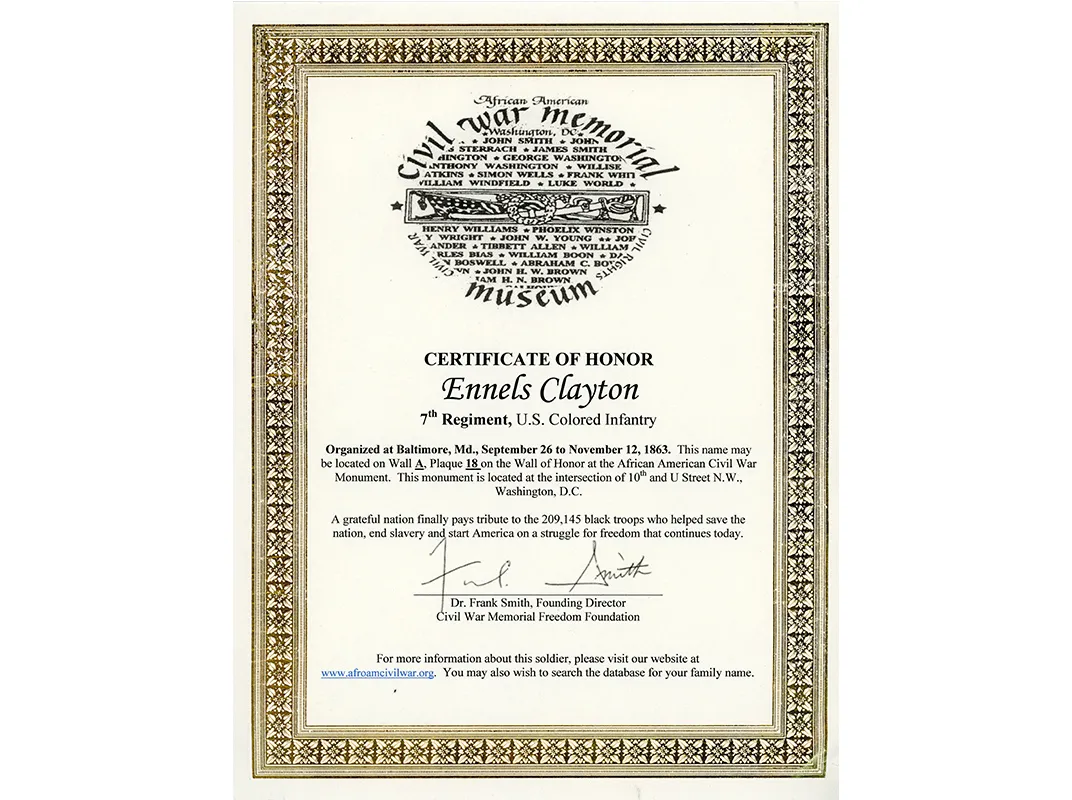

Once the Union began enlisting African-American troops, in 1863, some 8,700 black Marylanders seized the chance. (Some slaveholders accepted the Union’s offer of $300 per man to let them go.) After the war ended in 1865, eighteen black soldiers returned to Talbot County—including Charles and Benjamin Demby, relatives of the man whose murder Frederick Douglass described. In 1867, a Quaker couple, Ezekiel and Sarah Cowgill, who had always worked their Talbot plantations with paid labor, gave the veterans assistance that other landowners refused. The Cowgills began leasing half-acre lots to the 18, who would come to own them. The next year, the couple sold them a parcel for a schoolhouse, and then another for a church, which became St. Stephens AME. In time, 49 families called Unionville home.

The village was an island of black self-determination in a sea of white resentment. Some of Talbot’s emancipated workers spent years in forced “apprenticeships,” prison work camps and other measures meant to perpetuate the old caste system. Maryland passed Jim Crow laws as early as 1870. Sporadic lynchings on the Eastern Shore began in the 1890s. In 1916, a monument to the 84 “Talbot Boys” who fought for the Confederacy went up outside the county courthouse in Easton, just a few miles from Unionville. Not until the civil rights movement of the 1970s, Bernard Demczuk says, did Unionville’s relationship with its surroundings begin to improve.

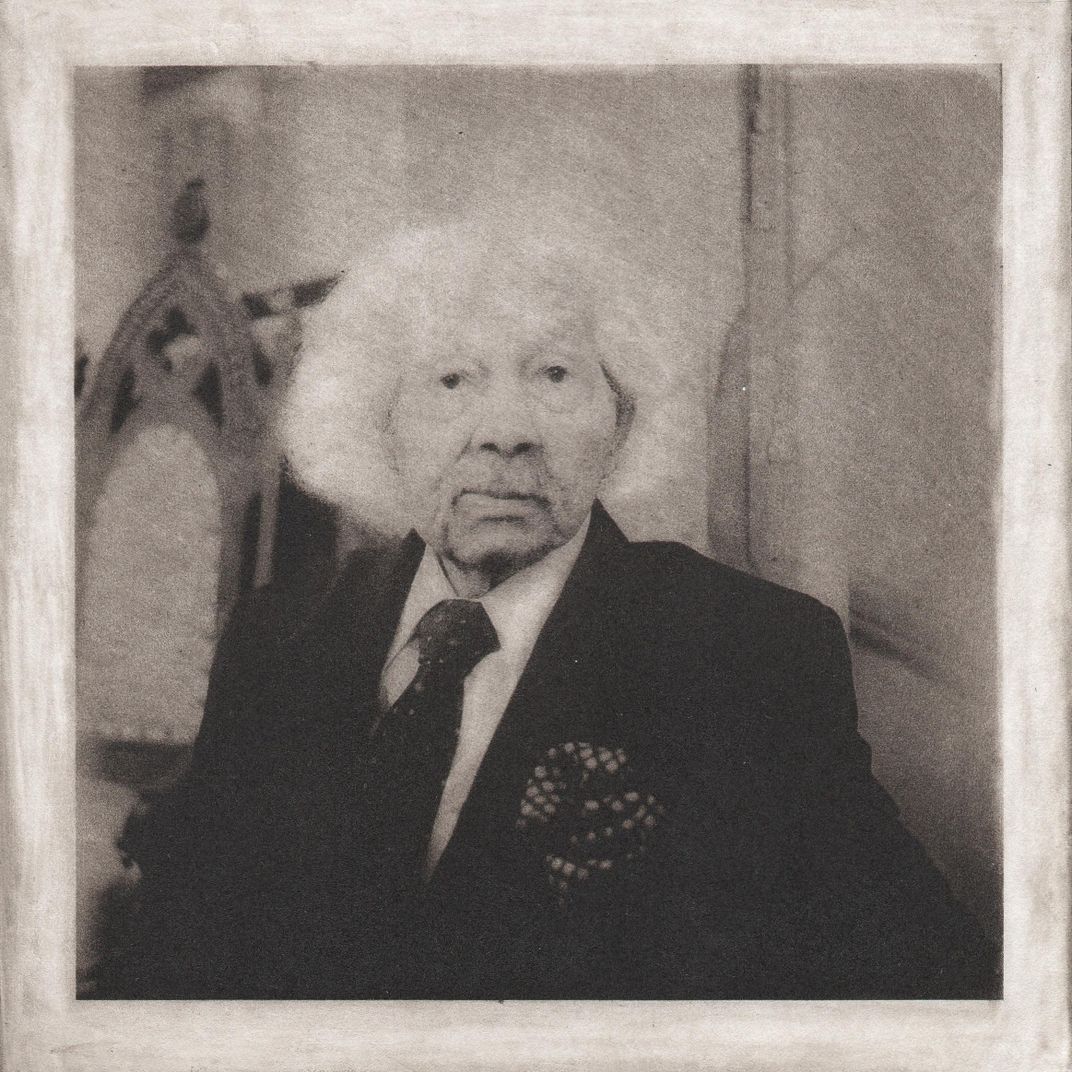

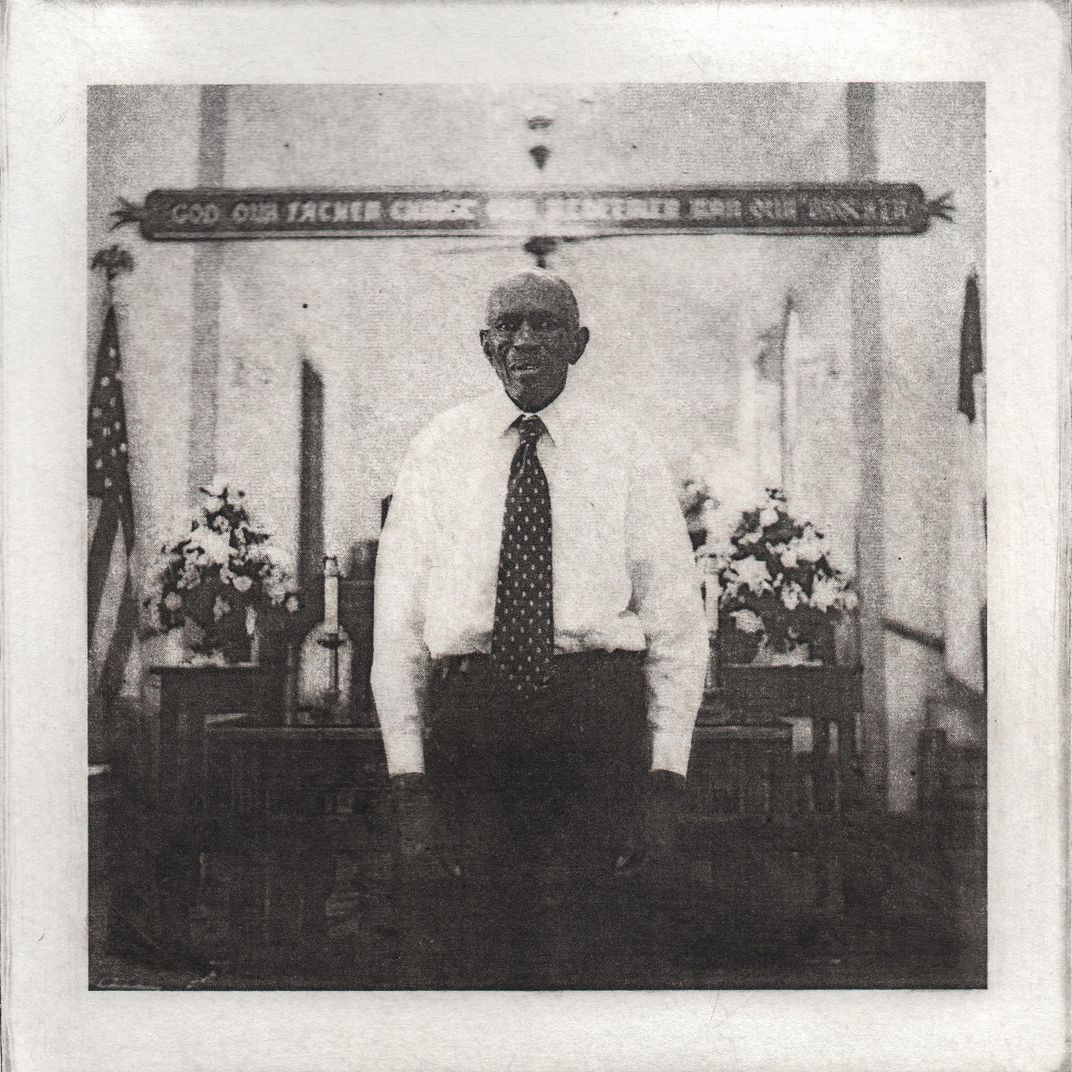

The 18 founders now lie in the graveyard at St. Stephens, and the descendants of all but a handful of the 49 families have moved on. Unionville is majority, but not exclusively, black, and Talbot County is becoming popular as a tourist and retirement haven. Still, “there is a vision of Unionville,” said the Rev. Nancy M. Dennis, pastor of St. Stephens, “and that is sacred memories on hallowed ground.”

Dennis was speaking on Memorial Day, when Unionville formally celebrated its sesquicentennial with a giant party featuring locals, people from neighboring towns, American Legion vets and marching bands. A dance company from Baltimore performed in Union blue regalia. A gray-haired white woman read a poem she wrote in the voice of an enslaved black man. Descendants of both the African-American founders and the white plantation owners for whom they’d toiled clapped, sang, marched, danced and feasted on crab cakes, chicken and waffles, shrimp, and crab rolls.

As in New Orleans and Charleston, civil rights activists have pushed to remove Confederate monuments, including the Talbot Boys, from the county courthouse, arguing their presence casts a pall over the halls of justice. The county has declined. But in 2011, local officials added a statue of Frederick Douglass there. Bernard Demczuk said he thinks that’s about right, having the Talbot Boys and Douglass juxtaposed, “so we can have that conversation.”

Bernadine Davis, 35, a member of St. Stephens and a descendant of Unionville founder Zachary Glasgow, said that conversation has yet to begin. “No one really talks about it,” she said. At the same time, the display of interracial fellowship at the sesquicentennial is now a way of life in Talbot County. “You do have your bickering and your arguing, but everyone is of one accord,” she says. “The majority of the black people of Unionville are family. The white people are family as well.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.