Civil War Geology

What underlies the Civil War’s 25 bloodiest battles? Two geologists investigate why certain terrain proved so hazardous

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bloody-Lane-Antietam-631.jpg)

Bob Whisonant is a Civil War buff with a peculiar way of looking at the Civil War. If you ask him to talk about, say, the Battle of Antietam, he might begin, “Well, it all started 500 million years ago.”

Whisonant is a geologist, trained to study how layers of sediment form. He worked first at an oil company, then as a professor at Radford University in Virginia for more than 30 years. It wasn’t long before his geologic training began to inform his longstanding fascination with the Civil War. When Whisonant learned that there were others like him, he began to attend conferences on what is known as military geology.

About a decade ago, he met Judy Ehlen, an Army Corps of Engineers geologist with similar interests, and the two hatched a plan: what might they learn by studying the geology underlying the Civil War’s 25 bloodiest battles? When they plotted those battles on a map, they found that nearly a quarter of them had been fought atop limestone—more than on any other kind of substrate. What’s more, those limestone battles were among the most gruesome of the list. “Killer limestone,” they called it.

But limestone is not inherently toxic. Why had it proved so hazardous? The key to the puzzle, they found, is that limestone erodes relatively easily. Over millions of years, limestone bedrock weathers into flat, open terrain. And as any soldier who has charged into enemy fire knows, open terrain “is a bad place to be,” as Whisonant puts it. He and Ehlen presented their work at the 2008 meeting of the Geological Society of America; an article is forthcoming in a book titled Military Geography and Geology: History and Technology.

Whisonant and Ehlen are quick to acknowledge that soldiers have known for thousands of years that terrain affects battles. But military geology takes things “a step deeper,” Whisonant says (with “no pun intended”). Where a military historian might note the importance of the high ground or available cover in a battle, geologists look at a longer chain of causation. By making the strata of battlefields their subject of study, they give greater context, and a new perspective, to old battlefields.

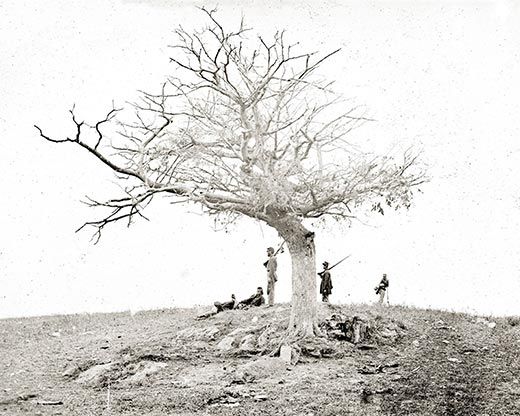

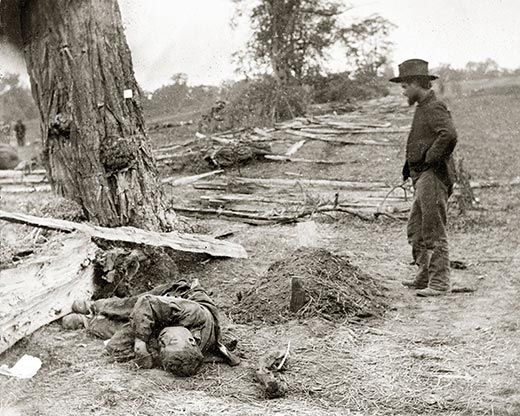

Take the battle of Antietam, which occurred on September 17, 1862. It remains the bloodiest day in American history—23,000 men died or were wounded on that battlefield—as well as one of the most strategically significant of the Civil War. The Union victory marked a turning point and emboldened President Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation a few days later.

The battlefield also offers one of the best illustrations of Civil War geology. Antietam was fought atop different types of bedrock: in one area was limestone; in another, dolomite. Over millions of years, these different bedrocks eroded into distinct terrains. The limestone area became flat and open. But because dolomite is harder than limestone, the dolomite areas eroded into less even terrain, filled with hills and ridges that provided some cover.

One result: the fighting atop the limestone produced casualties at almost five times the rate of the fighting atop the dolomite. Limestone underlies the section of the battleground called the Cornfield—“the single bloodiest piece of ground in Civil War history,” Whisonant says. There, the bullets flew so relentlessly that by the battle’s end, “it looked like a scythe had come through and mowed down the cornstalks.” There were 12,600 casualties after three hours of fighting at the Cornfield, or 4,200 casualties an hour; at Burnside Bridge, which sat atop dolomite, there were 3,500 casualties after four hours, or 875 an hour.

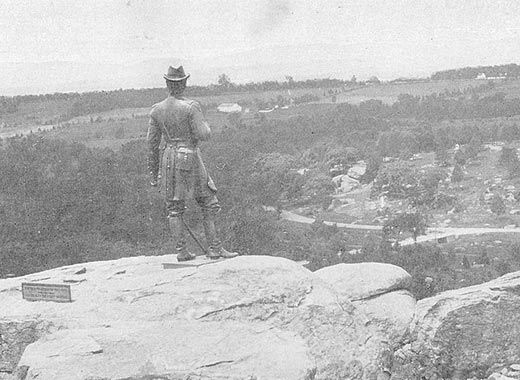

Beyond its role in shaping battlefield topography, geology affected Civil War battles in less intuitive ways. At Gettysburg, Union soldiers arrayed themselves along a high, rocky spine called Cemetery Ridge. It was a commanding position, but it had a disadvantage: when the Confederates began bursting shells above them, the Union soldiers found that they couldn’t dig foxholes into the rock.

Between battles, troop movements were fundamentally “constrained by geology,” says Frank Galgano of Villanova University, who previously taught military geology at West Point. There is an oft-repeated myth that the Battle of Gettysburg occurred where it did because a Union general brought his weary, ill-shod troops there in search of a shoe factory. The fact, Galgano says, is that eight roads converged at Gettysburg, so a confrontation was bound to occur there. Those roads, in turn, had been built along axes determined by the topography, which was formed by tectonic events. “This seminal event in American history occurred here because of something that happened eons ago,” Galgano says.

Military geologists acknowledge that their work reveals only one of many forces that influence the outcome of war. “Leadership, morale, dense woods…the list goes on and on,” Whisonant says. Plus, he points out that there are plenty of battles where the role of geology was minor. Even so, the lay of the land and its composition have long been recognized as crucial.

For that reason, armies have sought the counsel of geologists (or their contemporary equivalents) since ancient times. But not until the 20th century, Whisonant says, were there organized efforts to harness geologists’ knowledge in waging war. Today, military geologists work on a “whole wide range of things,” he says. How easily can troops march along a certain terrain? What vehicles can pass? How will weaponry affect the landscape? Before she retired from the Army Corps of Engineers in 2005, Judy Ehlen conducted research intended to help Army analysts learn to identify rock types from satellite and aerial imagery. Whisonant says he knows a geologist who is “looking at the geology of the area [Osama] bin Laden is supposedly in, helping the Department of Defense assess what will happen if a missile goes in a cave.”

So long as warfare is waged on Earth, armies will need people who study the planet’s surface. “Throughout history it’s always the same,” Galgano says, “and it will be the same 100 years from now.”

But it’s that war from over 100 years ago that keeps beckoning to Whisonant. He says he has been moved by his visits to battlefields from the American Revolution to World War II, but that the Civil War battlefields—with their level fields, their rolling hills, their rocky outcroppings—move him most. “The gallantry, the willingness to pay the last full measure, as Lincoln said, by both sides has really consecrated that ground,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)