Closing the Pigeon Gap

During the First World War, Allied birds outperformed their rivals and saved thousands of lives–all thanks to the efforts of one London pigeon fancier

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120417100044homing-pigeon-gap-history-world-war-i.jpg)

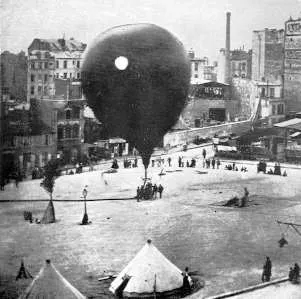

At midnight on November 12, 1870, two French balloons, inflated with highly flammable coal gas and manned by desperate volunteers, took off from a site in Monmartre, the highest point in Paris. The balloons rose from a city besieged—the Franco-Prussian War had left Paris isolated, and the city had been hastily encircled by the Prussian Army—and they did so on an unlikely mission. They carried with them several dozen pigeons, gathered from lofts across the city, that were part of a last-ditch attempt to establish two-way communication between the capital and the French provisional government in Tours, 130 miles southwest.

Paris had been encircled since mid-September. By early autumn, with the prospects of relief as distant as ever, and the population looking hungrily at the animals in the zoo, the besieged French had scoured the city and located seven balloons, one of which, the Neptune, was patched up sufficiently to make it out of the city over the heads of the astounded Prussians. It landed safely behind French lines with 275 pounds of official messages and mail, and before long there were other flights, and the capital’s balloon manufacturers were working flat out on new airships.

The work was dangerous and the flights no less so—2.5 million letters made it out of Paris during the siege, incalculably raising morale, but six balloons were lost to enemy fire and the ones that survived that gauntlet, historian Alastair Horne observes, “were capable of unpredictable motion in all three dimensions, none of which was controllable.”

Of the two balloons in the pigeon flight, one, the Daugerre, was shot down by ground fire as it drifted south of Paris in the dawn, but the other, the Niepce, survived by hastily jettisoning ballast and soaring out of range. Its precious pigeon cargo would return to the city bearing messages by the thousand, all photographed using the brand-new technique of microfilming and printed on slivers of collodium, each weighing just a hundredth of an ounce. These letters were limited to a maximum of 20 words and they were carried into Paris at a cost of 5 francs each. In this way, Horne notes, a single pigeon could fly in 40,000 dispatches, equivalent to the contents of a substantial book. The messages were then projected by magic lantern onto a wall, transcribed by clerks, and delivered by regular post.

A total of 302 largely untrained pigeons left Paris in the course of the siege, and 57 returned to the city. The remainder fell prey to Prussian rifles, cold, hunger, or the falcons that the besieging Germans hastily introduced to intercept France’s feathered messengers. Still, the general principle that carrier pigeons could make communication possible in the direst of situations was firmly established in 1870, and by 1899, Spain, Russia, Italy, France, Germany, Austria and Romania had established their own pigeon services. The British viewed these developments with some alarm. A call to arms published in the influential journal The Nineteenth Century expressed concern at the development of a worrying divergence in military capability. The Empire, it was suggested, was being rapidly outpaced by foreign military technology.

In this sense, if in no other, the “pigeon gap” of 1900 resembles the alleged “missile gap” that so frightened Americans at the height of the Cold War. Taking worried note of the activities of “Lieutenant Gigot, the eminent Belgian authority on homers,” who had devoted “no less than 41 pages to the military uses of pigeons”—and of the activities of the noble Spanish captain of engineers, Don Lorenzo de la Tegera y Magnin, who had devoted his career to the military lofts south of the Pyrenees—the journal lamented that Britain had no equivalent of the coast-to-coast networks developed by her rivals and worried: “How long must we wait until our pigeon system rivals those of the Continental Powers?”

People have known for thousands of years that some species of pigeons have an uncanny ability to find their way home to their roosts from almost any distance, though exactly how the birds manage their feats remains a subject of dispute. Scientists believe that pigeons combine what is termed “compass sense” with “map sense” to perform these feats. Observation suggests that “compass sense” allows the birds to orientate themselves by the sun—pigeons do not navigate well by night or in thick fog—but “map sense” remains very poorly understood. What can be said is that individual birds have been known to home across distances of more than a thousand miles.

Seen from this perspective, The Nineteenth Century had some reason to be concerned. “No animal,” contends Andrew Blechman,

has developed as unique and continuous a relationship with humans as the common pigeon…. The fanatical hatred of pigeons is actually a relatively new phenomenon…. Consider this: They’ve been worshipped as fertility goddesses, representations of the Christian Holy Ghost and symbols of peace; they’ve been domesticated since the dawn of man and utilized by every major historical superpower from ancient Egypt to the United States of America. It was a pigeon that delivered the results of the first Olympics in 776 BC and a pigeon that brought news of Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo.

From a military point of view, pigeons still had much to recommend them as late as the First World War. They ate little and were easy to transport. More important, they could travel at speeds well in excess 60 m.p.h.—an impressive achievement when the alternative method of communication was sometimes a man on horseback—and unlike the messenger dogs tried by the Germans at the height of the 1914-18 conflict, they could be relied on not to be distracted by the tempting smells of rats and rotting corpses. Captured homing pigeons betrayed nothing of their point of origin or their destination, and those that made it through completed their journeys tirelessly and as rapidly as possible.

Experience of war in the trenches confirmed that the birds would keep trying to home despite life-threatening injuries. The most celebrated of all military pigeons was an American Black Check by the name of Cher Ami, which successfully completed 12 missions. Cher Ami’s last flight came on October 4, 1918, when 500 men, forming a battalion of the 77th Infantry and commanded by Major Charles S. Whittlesey, found themselves cut off deep in the Argonne and under bombardment form their own artillery. Two other pigeons were shot down or lost to shell splinters, but Cher Ami successfully brought out a message from the “Lost Battalion” despite suffering appalling wounds.

By the time the bird made it back to its loft 25 miles away, it was blind in one eye, wounded in the breast, and the leg to which Whittlesey had attached his message was dangling from its body by a single tendon. The barrage was lifted, though, and nearly 200 survivors credited Cher Ami with saving their lives. The Americans carefully nursed the bird back to health and even fitted it with a miniature wooden leg before it was awarded the French Croix de Guerre with oak leaf cluster and repatriated. So great was Cher Ami’s fame and propaganda value that it was seen off by General John Pershing, the American commander-in-chief; when it died a year later, it was stuffed, mounted and donated to the American Museum of Natural History, where it remains on display.

Credit for the development of a British service that rivaled the best that the continent could offer belongs to the neglected figure of Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Osman, proprietor of a weekly newspaper called The Racing Pigeon. The Pigeon promoted competitive racing between highly trained homers and contributed to the development of a flourishing market for betting on individual birds. Volunteering in the autumn of 1914 to establish a Voluntary Pigeon War Committee (VPWC), Osman, a proud Londoner, was fully convinced that expert handling and British pluck could produce a vastly better bird than German fanciers possessed. Throughout the war, he insisted, “German birds were distinctly inferior to their British counterparts.”

Yet closing the pigeon gap proved to be no simple matter. The little attention devoted to the birds in the first months of the war was largely destructive. Convinced, wrongly, that their country was seething with German spies, the British became concerned over the possibility that information about troop movements might be carried back to the Continent by avian agents of the Imperial German pigeon service, and hundreds of pigeons were killed or had their wings clipped as a result. One “Danish” pigeon fancier with a loft in the center of London was unmasked early on as a German and swiftly disappeared into an English jail.

Osman—who insisted on serving throughout the war without pay—used his high-level contacts in the fancying world to persuade leading breeders to donate birds to the British cause. By the end of 1914 he and a small team of helpers had begun not only to systematically train the birds for operational service, but also to establish a network of lofts for them to fly from. At first, Osman’s efforts were restricted to the home front; by the beginning of 1915 he had set up a chain of lofts along the east coast and was supplying birds to the trawlers and seaplanes that patrolled the North Sea. It was vital work, particularly in the first months of the war; the greatest threat that Britain faced was a German naval breakout, either to cover an invasion or to menace merchant shipping, and until wireless telegraphy became commonplace, pigeons were the only way of swiftly getting messages of enemy naval movements home.

Osman trained his birds to cover distances of 70 to 150 miles as rapidly as possible, and though it was a struggle at first to convince the sailors who were issued with pigeons that they could be lifesavers (one bird found in Osman’s loft bore a trawler captain’s message “All well; having beef pudding for dinner”), early shipping losses quickly drove the message home.

On land, meanwhile, the horrors of trench warfare were making the same point. It was soon found that telegraph wires running from the front back to headquarters were easily cut by artillery bombardment and difficult to restore; signalers burdened with large coils of wire made excellent targets for snipers. Nor, in the years before the development of two-way radios, was it easy for units to remain in touch on the rare occasions that they went “over the top” in a full-scale frontal assault. In desperate circumstances, pigeons were greatly valued as a last-ditch option for sending vital messages.

Allied birds performed great feats in the course of the First World War. Dozens of British airmen fighting the war at sea owed their lives to the pigeons they carried in their seaplanes, which repeatedly returned to their lofts with SOS messages from pilots who had ditched in the North Sea. On land, meanwhile, Christopher Sterling notes,

pigeons turned out to be conveniently immune to tear gas, then so common in trench warfare. An Italian program used 50,000 pigeons, reporting that one pigeon message had helped to save 1,800 Italians and led to the capture of 3,500 Austrians.

For the most part, the work of pigeons was routine. Osman built up an impressively mobile signal service by mounting pigeon lofts on top of converted buses; these could be moved from place to place a mile or two behind the lines and held in reserve for times when normal communications became impossible.

But birds were also carried into battle, and their use in action was often fraught, particularly during the grim Passchendaele offensive, waged in the face of appalling weather in the autumn of 1917. After several weeks of rain, it was not uncommon for soldiers weighed down by heavy packs to slip into waterlogged shell-holes and drown, and for assaults to grind to a halt in the clinging mud.

It was in these awful conditions, recalled Lieutenant Alan Goring, that he and his men found themselves cut off close to the German lines and dependent on their pigeons to get a message calling for an artillery bombardment back to their headquarters. “We had a very busy time,” wrote Goring,

for naturally there were snipers all around us and bullets zinging all over the place. I was left with just a handful of men, all that was left out of those three platoons…. We had two pigeons in a basket, but the trouble was that the wretched birds had got soaked when the platoon floundered into the flooded ground. We tried to dry one of them off as best we could, and I wrote a message, attached it to its leg, and sent it off.

To our absolute horror, the bird was so wet that it just flapped into the air and then came straight down again, and started actually walking towards the German line. Well, if that message had got into the Germans’ hands, they would have known that we were on our own and we’d have been in real trouble. So we had to try to shoot the pigeon before he got there. A revolver was no good. We had to use rifles, and there we were, all of us, rifles trained over the edge of this muddy breastwork trying to shoot this bird scrambling about in the mud. It hardly presented a target at all.

Other birds, on other days, did better; figures compiled by the British pigeon service showed that messages sent during the Battle of the Somme got through in an average of not much more than 25 minutes, vastly faster than would have been possible by runner. Osman’s highly trained birds also comfortably outperformed the pigeons of the Franco-Prussian War; 98 percent of messages were delivered safely despite the dangers of shellfire and the massed efforts of German infantrymen to bring the birds down with rifle and machine-gun fire.

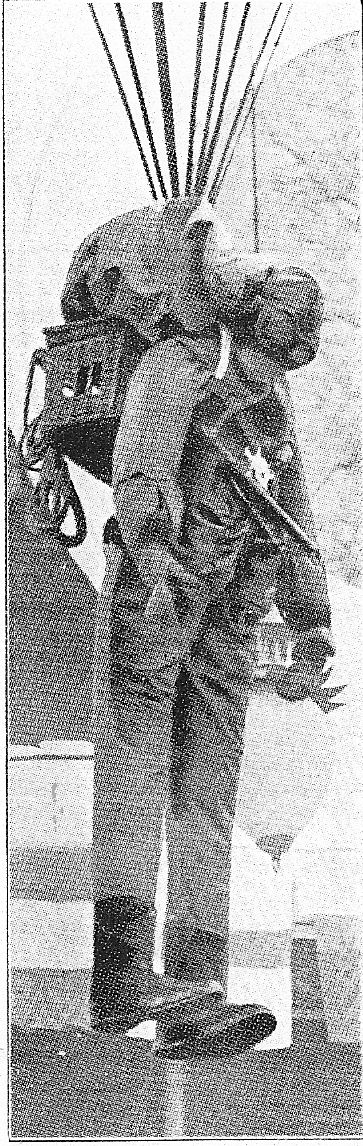

By the end of the war, the carrier pigeon service was also supplying birds to that newfangled British invention, the tank—where the pigeons, Osman confessed, “often became stupefied, no doubt due to the fumes of oil”—and they were also used increasingly in intelligence work. Here the VPWC’s efforts culminated in a scheme that involved “brave Belgian volunteers” parachuting into enemy-held territory strapped to a large basket full of homing pigeons, which they were to use to send information about enemy troop movements back to one of Osman’s lofts.

The scheme worked, the Colonel wrote, “except that at the outset great difficulty was experienced in getting the man to jump from the plane when the time came.” Such reluctance was understandable at a time when parachutes were still in the early stages of development, but the ingenious if stern-hearted Osman solved the problem in collaboration with the designers of the two-seater observation planes that had been adapted to carry out the missions: “A special aeroplane was designed in order that when the position was reached the seat upon which the man sat gave way automatically when the pilot let go a lever,” he wrote, sending the hapless Belgian spy plummeting earthward with no option but to open his ‘chute.

This sort of versatility ensured that the British pigeon corps remained fully employed until the end of the war despite advances in technology that made radio, telegraphy and telephone communications much more certain. By the end of the war the VPWC employed 350 handlers and Osman and his men had trained and distributed an astonishing 100,000 birds. Nor were their allies found wanting; in November 1918 the equivalent American service, put together in only a fraction of the time, consisted of nine officers, 324 men, 6,000 pigeons and 50 mobile lofts.

The pigeon gap had been well and truly closed.

Sources

Andrew Blechman. Pigeons: The Fascinating Saga of the World’s Most Revered and Reviled Bird. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2006; Hermann Cron. Imperial German Army, 1914-18: Organisation, Structure, Order of Battle. Solihull: Helion & Company, 2006; Richard Van Emden. Tommy’s Ark: Soldiers and Their Animals in the Great War. London: Bloomsbury, 2011; Alistair Horne. Seven Ages of Paris: Portrait of a City. London: Macmillan, 2002; John Kistler. Animals in the Military: From Hannibal’s Elephants to the Dolphins of the US Navy. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2011; Hilda Kean. Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain Since 1800. London: Reaktion Books, 1998; George Lamer. “Homing pigeons in wartime.” In The Nineteenth Century, vol.45, 1899; Alfred Osman. Pigeons in the Great War: A Complete History of the Carrier Pigeon Service 1914 to 1918. London: Racing Pigeon Publishing Company, 1928; Christopher Sterling. Military Communications: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2008.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)