Coffee’s Dark History, the Sinking of the World’s Most Glamorous Ship and Other New Books to Read

The third installment in our weekly series spotlights titles that may have been lost in the news amid the COVID-19 crisis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/70/9d70c262-a24e-4239-b0ee-f3c7b81f0719/booksweek3.jpg)

In times of stress, coffee acts as many individuals’ comfort food, a caffeine-fueled coping mechanism enabled by a culture that has placed the drink within reach of nearly anyone looking for a fix. But few realize that the beloved beverage’s history is marred by exploitation and violence—a dark past strikingly laid out in Augustine Sedgewick’s Coffeeland, one of five new nonfiction titles featured in Smithsonian magazine’s weekly books roundup.

The latest installment in our “Books of the Week” series, which launched in late March to support authors whose works have been overshadowed amid the COVID-19 pandemic, details coffee’s hidden history, the sinking of the world’s most glamorous ship, interwar London literary circles, technological innovation and an American family’s struggle with schizophrenia.

Representing the fields of history, science, arts and culture, innovation, and travel, selections represent texts that piqued our curiosity with their new approaches to oft-discussed topics, elevation of overlooked stories and artful prose. We’ve linked to Amazon for your convenience, but be sure to check with your local bookstore to see if it supports social distancing-appropriate delivery or pickup measures, too.

Coffeeland: One Man's Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug by Augustine Sedgewick

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a5/e7/a5e7b5bb-7923-40d8-8a17-8e4a7781d230/coffee.jpg)

In 1889, James Hill, an 18-year-old Englishman from the slums of Manchester, set sail for El Salvador in hopes of making a name for himself. He succeeded in this mission, building a coffee empire that endures to this day, but by creating a culture of “extraordinary productivity,” argues historian Augustine Sedgewick, the entrepreneur also sparked rampant “inequality and violence”—a disparity now evident in the coffee-bred “vast wealth and hard poverty at once connecting and dividing the modern world.”

As Michael Pollan writes in the Atlantic’s review of Coffeeland—a term used to describe both the United States and El Salvador, albeit for vastly different reasons—Hill modeled his plantation economy on Manchester’s industrial might, depriving locals of their longtime subsistence farming and foraging lifestyle by eradicating all crops except coffee. Communal farmland gave way to private plantations, and thousands of indigenous individuals (male mozos picked coffee beans, while female limpiadoras cleaned them) became “wage laborers, extracting quantities of surplus value that would be the envy of any Manchester factory owner” in exchange for meager payment and daily food rations.

Explains Sedgewick, “What was needed to harness the will of the Salvadoran people to the production of coffee, beyond land privatization, was the plantation’s production of hunger itself.”

The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another by Ainissa Ramirez

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/9d/a09d429c-0f92-41f7-8d77-2c0204c153ad/alchemy.jpg)

Material scientist Ainissa Ramirez offers up a highly readable exploration of how eight inventions—quartz clocks, steel rails, copper communication cables, silver photographic film, light bulbs, hard disks, labware and silicon chips—have both intentionally and inadvertently shaped our world. Placing a particular emphasis on people of color and women inventors, Ramirez draws surprising connections between Christmas and the rise of railroads, clocks and the demise of “segmented sleep” cycles, and Ernest Hemingway’s abbreviated writing style and the telegram, among other trends.

As Ramirez writes in the book’s introduction, “The Alchemy of Us fills in the gaps of most books about technology by telling the tales of little-known inventors, or by taking a different angle to well-known ones.” In doing so, she hopes to demonstrate how everyday inventions have “radically altered how we interact, connect, convey, capture, see, share, discover and think.”

The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria: The Sinking of the World’s Most Glamorous Ship by Greg King and Penny Wilson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/d8/45d8093b-aea4-42de-8003-22d703bbf30b/andrea_doria.jpg)

Unlike the Titanic, which sank on its maiden voyage, the Andrea Doria had a proven track record of safe sea travel. When the luxurious ocean liner departed Italy for New York on July 17, 1956, the ship was actually poised to make its 101st successful transatlantic crossing. Then, at 11:22 p.m. on July 25, disaster struck: A Swedish passenger liner called the Stockholm collided with the Doria at an almost 90-degree angle, tearing a 40-foot opening in the Italian ship’s side. Fifty-one people (46 aboard the Doria and 5 on the Stockholm) died in the ensuing chaos, and at 10:09 a.m. the following morning, the damaged Doria—renowned for its glamorous swimming pools, modern decor and “floating art gallery”—vanished from view forever.

Greg King and Penny Wilson’s The Last Voyage of the Andrea Doria revisits the tragedy from the perspective of its passengers, including the “flamboyant” mayor of Philadelphia, Betsy Drake (the wife of actor Cary Grant), an heiress and Italian immigrants seeking a better life abroad. Drawing on “in-depth research, interviews with survivors and never-before-seen-photos of the wreck as it is today,” according to publicity materials, the book details how the maritime disaster played out in real-time via radio and television, becoming the “first disaster of the modern age.” With the ship’s sinking, the authors write, the golden age of ocean liners—a mode of travel already threatened by commercial airlines—essentially came to an end.

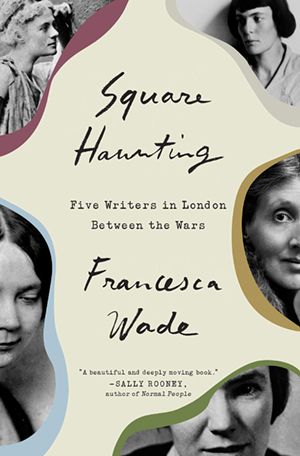

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade

Between 1918 and 1939, a London neighborhood called Mecklenburgh Square hosted five women writers of varying levels of fame. None of the quintet’s members lived in the area at the same time, points out Johanna Thomas-Corr for the Guardian, and few were acquainted personally, “though they did share lovers and landladies.”

Still, Francesca Wade argues in Square Haunting, the group of five—author Virginia Woolf, detective novelist Dorothy L. Sayers, poet Hilda Doolittle (better known by her initials H.D.), classicist Jane Harrison and economic historian Eileen Power—shared more than just a London postcode: Amid the changing tides of the interwar period, each of these women turned to the city in search of creative and personal independence.

As Wade writes in a sentence echoing Woolf’s seminal feminist essay of the same name, “At last, here was a district of the city where a room of one’s own could be procured.”

Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family by Robert Kolker

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/da/28da53e7-1418-4b93-87db-2aa4e22bb0f7/american_family.jpg)

Between 1945 and 1965, Don and Mimi Galvin of Colorado Springs, Colorado, welcomed 12 children—10 boys and 2 girls—into their family. To outsiders, the Galvins seemingly exemplified the American Dream. But as Robert Kolker, author of 2014 bestseller Lost Girls, reveals in Hidden Valley Road, beneath this veneer of respectability was a household on the brink of disaster. By the mid-1970s, 6 of the couple’s 12 children had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, a still-poorly understood condition that, at the time, was largely unfathomable.

Kolker’s heart-wrenching narrative emphasizes the six schizophrenic brothers’ individuality, from one’s talent for art to another’s career as a musician. But it never shies away from portraying the toll exacted by the siblings’ shared mental illness, both on the boys themselves and on the family members left to cope with their loved ones’ increasingly erratic, violent behavior. Particularly poignant are the segments dedicated to Margaret and Mary—sisters who “suffered tremendous psychological and sexual abuse from being in their [brothers’] orbit,” according to the Washington Post’s Karen Iris Tucker—and their mother, Mimi, who often refused to recognize her sons’ outbursts for fear of admitting she lacked “any real control over the situation.”

Hidden Valley Road places the Galvins’ story within the broader context of scientists’ evolving understanding of schizophrenia, debunking the idea that poor parenting is responsible for the disease while acknowledging the limitations of researchers’ search for genetic markers of the condition. What may prove most useful in the end, the author suggests, are early detection methods coupled with “soft intervention” techniques centered on therapy, family support and limited medication.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)