Colonel Parker Managed Elvis’ Career, but Was He a Killer on the Lam?

The man who brought The King to global fame kept his own past secret. But what exactly was Tom Parker hiding?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/colonel-parker-elvis.jpg)

The Colonel always was a mystery. But that was very much the way he liked it.

It was, of course, a tough trick to pull off, because the Colonel’s name was Tom Parker, and Tom Parker managed Elvis Presley. Since Elvis was the biggest name in the entertainment industry, his manager could hardly help appearing in the spotlight, too. For the most part that was not a problem, because Parker had showman’s instincts and enjoyed publicity. But, even so, he was always anxious to ensure that attention never settled for very long on two vexed questions: exactly who he was and where he came from.

So far as the wider world knew, the Colonel was Thomas Andrew Parker, born in Huntingdon, West Virginia, some time shortly after 1900. He had toured with carnivals, worked with elephants and managed a palm-reading booth before finding his feet in the early 1950s as a music promoter. Had anyone taken the trouble to inquire, however, they would have discovered that there was no record of the birth of any Thomas Parker in Huntingdon. They might also have discovered that Tom Parker had never held a U.S. passport—and that while he had served in the U.S. Army, he had done so as a private. Indeed, Parker’s brief military career had ended in ignominy. In 1932, he had gone absent without leave and served several months in military prison for desertion. He was released only after he had suffered what his biographer Alanna Nash terms a “psychotic breakdown.” Diagnosed as a psychopath, he was discharged from the Army. A few years later, when the draft was introduced during the World War II, Parker ate until he weighed more than 300 pounds in a successful bid to have himself declared unfit for further service.

For the most part, these details did not emerge until the 1980s, years after Presley’s death and well into the Colonel’s semi-retirement (he eventually died in 1997). But when they did they seemed to explain why, throughout his life, Parker had taken such enormous care to keep his past hidden—why he had settled a lawsuit with Elvis’ record company when it became clear that he would have to face cross-examination under oath, and why, far from resorting to the sort of tax-avoidance schemes that managers typically offered to their clients, he had always let the IRS calculate his taxes. The lack of a passport might even explain the single greatest mystery of Presley’s career: why the Colonel had turned down dozens of offers, totaling millions of dollars, to have his famous client tour the world. Elvis was just as famous in London, Berlin and Tokyo–yet in a career of almost 30 years, he played a total of only three concerts on foreign soil, in Canada in 1957. Although border-crossing formalities were minimal then, the Colonel did not accompany him.

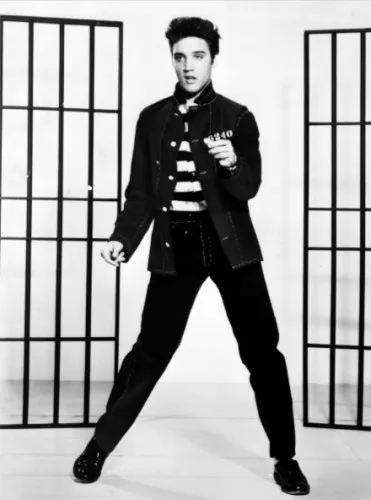

Although it took years for the story to leak out, the mystery of the Colonel’s origins had actually been solved as early as the spring of 1960, in the unlikely surrounds of a hairdressers’ salon in the Dutch town of Eindhoven. There a woman by the name of Nel Dankers-van Kuijk flicked through a copy of Rosita, a Belgian women’s magazine. It carried a story about Presley’s recent discharge from the U.S. Army, illustrated by a photo of the singer standing in the doorway of a train and waving to his fans. The large figure of Elvis’s manager, standing grinning just behind his charge, made Dankers-van Kuijk jump.

The man had aged and grown grotesquely fat. But she still knew him as her long-lost brother.

Far from being born in West Virginia, Tom Parker was in fact a native of the city of Breda, in the southern part of the Netherlands. He had been born there in June 1909, the seventh child of a delivery driver and his wife. His real name was Andreas van Kuijk–”Dries” (pronounced “Drees”) to his family–and as far as anyone could tell, he changed it to Tom Parker because that was the name of the officer who interviewed him when he signed up for the Army. Huntington, West Virginia, meanwhile, was a stop along the route of the carnivals that the Dutch teenager worked when he first came to the States. Parker, or Van Kuijk, had other secrets too. Not the least of them was that he was an illegal immigrant, reaching the United States most probably through Canada. Nor had he ever been naturalized as an American.

The Colonel was largely able to suppress all these unwelcome details; when his overjoyed family sent a brother to the States to see him, the Colonel received him coolly—worried, apparently, that his mother and his siblings might be after money. When brother Ad returned to Breda, moreover, he remained perplexingly silent on the subject of Dries’s glamorous new life. He hadn’t talked much about personal matters, Nash reports, beyond mentioning that he had painted sparrows yellow and sold them as canaries. Some members of the family suspected that Parker had paid him not to talk.

Details of Van Kuijk’s childhood in Breda eventually emerged a few years later, but only in It’s Elvis Time, a small-circulation Dutch fan magazine. From there, they were picked up in the late 1970s by Elvis biographer Albert Goldman. But as late as 1982, the idea that Parker had not been born American was still little more than rumor in the States.

The Colonel’s exposure as an illegal immigrant makes it easier to understand his deep reluctance to leave the States—or even, as he once confided to a trusted assistant, to pick up the check he had earned while working his passage from the Netherlands. But his apparent unwillingness to solve what should have been a minor problem does remain a puzzle. After all, the Alien Registration Act of 1940 had offered an effective amnesty to all illegals, and when Elvis made it big his manager made plenty of powerful new friends. By the 1960s, Parker could have placed a phone call directly to Lyndon Johnson to smooth out any problems with his naturalization.

Only when Elvis died, in 1977, at age 42, did the first hints emerge that something far more unpleasant was lurking in the Colonel’s past, and once again they did so in the Netherlands. There, in Parker’s hometown, a journalist named Dirk Vellenga got a tip–it was “Do you know that Tom Parker comes from Breda? His father was a stableman for van Gend en Loos on the Vlaszak,” he recalled for Alanna Nash—and set on what would become a 30-year search for the truth about the Colonel.

At first, all Vellenga’s inquiries turned up was old tales from the Van Kuijk family, who still remembered how their Dries had been the family storyteller and liked to dress as a dandy. But his investigation took a much more sinister turn after he received a second tip in 1980.

Vellenga had been filing occasional updates on the Parker story—the Colonel was by far the most famous son of Breda—and found that he was building a detailed picture of what was by any standard a hasty departure. Parker, he learned, had vanished in May 1929 without telling any of his family or friends where he was heading, without taking his identity papers, and without money or even the expensive clothing he had spent most of his wages on. “This means,” notes Nash, that “he set out in a foreign country literally penniless.” In the late 1970s, Vellenga ended one of his newspaper features by posing what seemed to him a reasonable question: “Did something serious happen before Parker left that summer in 1929, or maybe in the 1930s when he broke all contact with his family?”

At least one of his readers thought that question deserved an answer, and a short while later an anonymous letter was delivered to Vellenga’s paper. “Gentlemen,” it began.

At last, I want to say what was told to me 19 years ago about this Colonel Parker. My mother-in-law said to me, if anything comes to light about this Parker, tell them that his name is Van Kuijk and that he murdered the wife of a greengrocer on the Bochstraat….

This murder has never been solved. But look it up and you will discover that he, on that very night, left for America and adopted a different name. And that is why it is so mysterious. That’s why he does not want to be known.

Turning hastily to his newspaper’s files, Vellenga found to his amazement that there had indeed been an unsolved killing in Breda in May 1929. Anna van den Enden, a 23-year-old newlywed, had been battered to death in the living quarters behind her store—a greengrocer’s on the Bochstraat. The premises had then been ransacked, apparently fruitlessly, in a search for money. After that, the killer had scattered a thin layer of pepper around the body before fleeing, apparently in the hope of preventing police dogs from picking up his scent.

The discovery left Vellenga perplexed. The 19 years of silence that his mysterious correspondent mentioned took the story as far back as 1961—exactly the year that the Van Kuijk family had made contract with Parker, and Ad van Kuijk had returned from his visit to the Colonel so remarkably tight-lipped. And the spot where the murder had occurred was only a few yards away from what had been, in 1929, Parker’s family home. Members of the Colonel’s family even recalled that he had been paid to make deliveries for a greengrocer in the area, though they could no longer remember which one.

The evidence, though, remained entirely circumstantial. Not a single witness at the time suggested that Andreas van Kuijk had ever been a suspect. And when Alanna Nash went through the Dutch courts to obtain a copy of the original police report on the murder, she found that nowhere in its 130 handwritten pages was there any mention of the young man who would become the Colonel. The most she could point to were a series of eyewitness statements that suggested the killer had been an unusually well-dressed man, clad in a bright coat—light yellow, always Tom Parker’s favorite color.

The mystery of Anna van den Enden’s death is unlikely to be solved; the original investigation was woefully inadequate, and every one of the witnesses is dead. What remains is the curious coincidence of Parker’s hasty disappearance, the evidence that he was psychopathic—and the testimony of those who knew him as a man of ungovernable temper.

“I really don’t think that there was murder in him,” Todd Slaughter of the Elvis Presley Fan Club of Great Britain told Alanna Nash after knowing Parker for a quarter-century. But others in the Colonel’s circle disagreed. “I don’t think that there’s any doubt he killed that woman,” said Lamar Fike, a member of Elvis Presley’s Memphis Mafia. “He had a terrible temper. He and I got into some violent, violent fights.”

“It took very little to set him off,” added Parker’s assistant, Byron Raphael.

In those fits of rage, he was a very dangerous man, and he certainly appeared capable of killing. He would be nice one second, and stare off like he was lost, and then–boom!–tremendous force. He’d just snap. You never saw it coming. Then five minutes later, he would be so gentle, telling a nice soft story.

Nash and Vellenga have their own version of events, one that they insist best fits the facts. Parker, they suggest, went to van den Enden’s store looking for money to fund his emigration to America. Probably he had known the woman; perhaps he had even desired her—and then been angered by her recent marriage. Either way, what had been meant as the robbery of an empty store had gone wrong, and, in a sudden burst of fear and temper, the Colonel had lashed out and killed a woman without meaning to.

That version doesn’t fully fit the facts; it’s impossible to know now within a week when Parker left the Netherlands, and hence how closely his departure coincided with the Breda murder. And Nash, Vellenga and every other biographer of both Presley and Parker acknowledge that the Colonel never showed much interest in women. He had no children, and he treated his wife as a companion, not as a lover. But, backed by some members of the Van Kuijk family, Nash still believes it more likely than not that Colonel Parker was a killer.

It could have been a coincidence, yes, of course. I cannot say without reservation that he killed this woman. I offer it only as a theory, a possibility. Even his Dutch family is willing to admit that it is a possibility, though they believe, as I do, that if he killed her, it was an accident.

I will say that he had an amazing ability to compartmentalize events and feelings in his mind. If something troubled him too much, he was able to store it in a back corner of his consciousness, though he always had trouble keeping it there. Certainly whatever happened in Holland that made him leave his family, with whom he was very close, and to just cut them off, was of a very grave nature. He missed them, but didn’t want to foist his troubles off on them. I know that from a letter he wrote to his nephew in the ’60s after his family identified him from a magazine photo and began to write to him.

Nash sums things up this way: “I want to be clear in saying that there is no hard proof that he committed this murder, in my heart of hearts, I believe he did. Certainly the way he lived his life, for the duration of his years, suggests a secret of that kind of gravity. In other words, if that’s not what happened back in Holland, something equally awful did.”

Sources

Dineke Dekkers. “Tom Parker… American or Dutchman?” It’s Elvis Time, April 1967; Alanna Nash. The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. London: Aurum 2003; Dirk Vellenga with Mick Farran. Elvis and the Colonel. New York: Delacorte Press, 1988.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)