Commemorating 100 Years of the RV

For almost as long as there have been automobiles, recreational vehicles have been traversing America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/RV-Adams-Motor-Bungalo-1917-631.jpg)

Every December 15, Kevin Ewert and Angie Kaphan celebrate a “nomadiversary,” the anniversary of wedding their lives to their wanderlust. They sit down at home, wherever they are, and decide whether to spend another year motoring in their 40-foot recreational vehicle.

Their romance with the road began six years ago, when they bought an RV to go to Burning Man, the annual temporary community of alternative culture in the Nevada desert. They soon started taking weekend trips and, after trading up to a bigger RV, motored from San Jose to Denver and then up to Mount Rushmore, Deadwood, Sturgis, Devil’s Tower and through Yellowstone. They loved the adventure, and Ewert, who builds web applications, was able to maintain regular work hours, just as he’d done at home in San Jose.

So they sold everything, including their home in San Jose, where they’d met, bought an even bigger RV, and hit the road full time, modern-day nomads in a high-tech covered wagon. “What we’re doing with the RV is blazing our own trail and getting out there and seeing all these places,” Ewert says. “I think it’s a very iconic American thing.”

The recreational vehicle turns 100 years old this year. According to the Recreational Vehicle Industry Association, about 8.2 million households now own RVs. They travel for 26 days and an average of 4,500 miles annually, according to a 2005 University of Michigan study. The institute estimates about 450,000 of them are full-time RVers like Ewert and Kaphan.

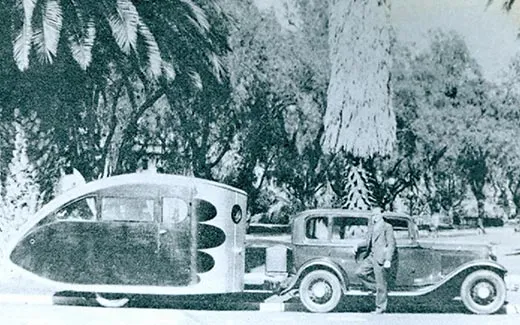

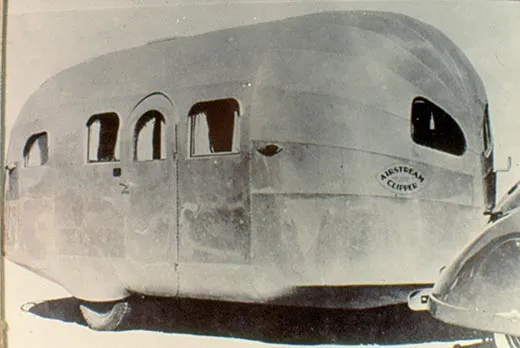

Drivers began making camping alterations to cars almost as soon as they were introduced. The first RV was Pierce-Arrow’s Touring Landau, which debuted at Madison Square Garden in 1910. The Landau had a back seat that folded into a bed, a chamber pot toilet and a sink that folded down from the back of the seat of the chauffeur, who was connected to his passengers via telephone. Camping trailers made by Los Angeles Trailer Works and Auto-Kamp Trailers also rolled off the assembly line beginning in 1910. Soon, dozens of manufacturers were producing what were then called auto campers, according to Al Hesselbart, the historian at the RV Museum and Hall of Fame in Elkhart, Indiana, a city that produces 60 percent of the RVs manufactured in the United States today.

As automobiles became more reliable, people traveled more and more. The rise in popularity of the national parks attracted travelers who demanded more campsites. David Woodworth—a former Baptist preacher who once owned 50 RVs built between 1914 and 1937, but sold many of them to the RV Museum—says in 1922 you could visit a campground in Denver that had 800 campsites, a nine-hole golf course, a hair salon and a movie theater.

The Tin Can Tourists, named because they heated tin cans of food on gasoline stoves by the roadside, formed the first camping club in the United States, holding their inaugural rally in Florida in 1919 and growing to 150,000 members by the mid-1930s. They had an initiation; an official song, “The More We Get Together;” and a secret handshake.

Another group of famous men, the self-styled Vagabonds—Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone and naturalist John Burroughs—caravaned in cars for annual camping trips from 1913 to 1924, drawing national attention. Their trips were widely covered by the media and evoked a desire in others to go car camping (regular folks certainly didn’t have their means). They brought with them a custom Lincoln truck outfitted as a camp kitchen. While they slept in tents, their widely chronicled adventures helped promote car camping and the RV lifestyle. Later, CBS News correspondent Charles Kuralt captured the romance of life on the road with reports that started in 1967, wearing out motor homes by covering more than a million miles over the next 25 years in his “On the Road” series. “There’s just something about taking your home with you, stopping wherever you want to and being in the comfort of your own home, being able to cook your own meals, that has really appealed to people,” Woodworth says.

The crash of 1929 and the Depression dampened the popularity of RVs, although some people used travel trailers, which could be purchased for $500 to $1,000, as inexpensive homes. Rationing during World War II stopped production of RVs for consumer use, although some companies converted to wartime manufacturing, making units that served as mobile hospitals, prisoner transports and morgues.

After the war, the returning GIs and their young families craved inexpensive ways to vacation. The burgeoning interstate highway system offered a way to go far fast and that combination spurred a second RV boom that lasted through the 1960s.

Motorized RVs started to become popular in the late 1950s, but they were expensive luxury items that were far less popular than trailers. That changed in 1967 when Winnebago began mass-producing what it advertised as “America’s first family of motor homes,” five models from 16 to 27 feet long, which sold for as little as $5,000. By then, refrigeration was a staple of RVs, according to Hesselbart, who wrote The Dumb Things Sold Just Like That, a history of the RV industry.

“The evolution of the RV has pretty much followed technology,” Woodworth says. “RVs have always been as comfortable as they can be for the time period.”

As RVs became more sophisticated, Hesselbart says, they attracted a new breed of enthusiasts interested less in camping and more in destinations, like Disney World and Branson, Missouri. Today, it seems that only your budget limits the comforts of an RV. Modern motor homes have convection ovens, microwaves, garbage disposals, washers and dryers, king-size beds, heated baths and showers and, of course, satellite dishes.

“RVs have changed, but the reason people RV has been constant the whole time,” Woodworth says. “You can stop right where you are and be at home.”

Ewert chose an RV that features an office. It’s a simple life, he says. Everything they own travels with them. They consume less and use fewer resources than they did living in a house, even though the gas guzzlers get only eight miles a gallon. They have a strict flip-flops and shorts dress code. They’ve fallen in love with places like Moab and discovered the joys of southern California after being northern California snobs for so long. And they don’t miss having a house somewhere to anchor them. They may not be able to afford a house in Malibu down the street from Cher’s place, but they can afford to camp there with a million-dollar view out their windows. They’ve developed a network of friends on the road and created NuRvers.com, a Web site for younger RV full-timers (Ewert is 47; Kaphan is 38).

Asked about their discussion on the next December 15, Ewert says he expects they’ll make the same choice they have made the past three years—to stay on the road. “We’re both just really happy with what we’re doing,” he says. “We’re evangelical about this lifestyle because it offers so many new and exciting things.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)