What Happened When Violence Broke Out on Cleveland’s East Side 50 Years Ago?

In the summer of 1968, the neighborhood of Glenville erupted in “urban warfare,” leaving seven dead and heightening police-community tensions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/6a/e56a4661-e796-401d-b012-aa6241d59d0c/smouldering_fire_superior__and_e_105th_st-wr.jpg)

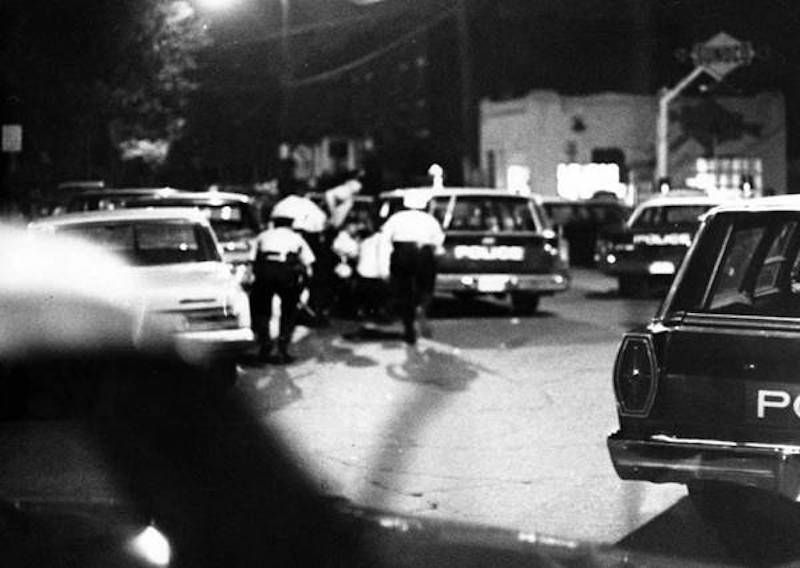

For several hours, gunfire engulfed the African-American neighborhood of Glenville on the east side of Cleveland. The Black Nationalists of New Libya exchanged shots with the Cleveland Police Department from apartments and homes. By the end of the night, seven men had been killed, including three police officers, three black nationalists, and one civilian. Several houses in the Glenville neighborhood were on fire, and at least 15 individuals were injured; more casualties may not have been reported due to neighborhood fears of police.

Today, the story of the Glenville shootout is still contentious. It’s unclear who shot first, or what exactly sparked the eruption. But for all that remains a mystery, the incident undeniably continues to affect the citizens of the neighborhood as they grapple with a legacy of antagonistic relations with the police.

***

Fred “Ahmed” Evans grew up on the east side of Cleveland in the mid-1930s and entered the Army in 1948 after dropping out of high school. He served in the Korean War until a bridge he was working on collapsed, causing back, shoulder and head injuries. Army physicians later found that Evans suffered from partial disabilities and psychomotor epilepsy, which affected his moods. When Evans moved back to Cleveland, “he became intensely aware of racialized violence and, alongside his military experiences, the power of the state and its support of racist sensibilities,” writes historian Rhonda Williams in Concrete Demands: The Search for Black Power in the 20th Century. Evans joined the Republic of New Libya, a black nationalist group advocating for social and political justice for African-Americans and armed self-defense. By 1966, Evans was the group’s leader.

At the time, Cleveland was a major hub for the Civil Rights Movement. Around 50 separate Civil Rights groups operated there, from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to the Black Muslims. The city elected Carl Stokes as mayor in 1967, making him the first African-American mayor of a major city in the United States.

Stokes had his work cut out for him. “Never before had a nation thrived—grown in population and in wealth—while its major cities decayed,” write historians David Stradling and Richard Stradling in Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland. “The city bore the burdens of racism and segregation, which combined to keep black residents poor and confined, powerless to improve their neighborhoods and subject to the brunt of urban violence, while whites fled to more prosperous communities.” Communities on the east side of Cleveland dealt with schools that weren’t fully integrated, dwindling economic opportunities, and regular harassment from the police.

Meanwhile, the FBI had taken urban troubles into their own hands with COINTELPRO, shorthand for the “Counterintelligence Program." While it began as a way to disrupt the Communist party, the program slowly shifted to target the Black Panthers and other black nationalist groups. Throughout much of the 1960s, cities convulsed in sporadic bouts of violence—uprisings in African-American communities that occurred in response to discrimination, segregation and police brutality. In 1967 there had been upheaval in Detroit and Newark, and in the spring of 1968 cities across the nation erupted following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

All those issues came to a head the night of July 23, 1968, in Glenville, a thriving neighborhood home to shops and restaurants catering to its African-American residents. Evans lived there, as did many of his fellow black nationalists. Earlier that day, he met with two politically connected allies who relayed to him that the FBI was warning the city government that Evans was planning an armed uprising. The Cleveland police decided to respond by stationing surveillance vehicles around Evans's home.

His acquaintances, a city councilman and a former Cleveland Browns football player, hoped that talking to Evans might quell any potential disruption. But Evans insisted he felt unsafe, and was arming himself out of self-preservation. After experiencing months of harassment from law enforcement when they repeatedly closed his Afro culture store, Evans felt he had plenty of reason to be fearful.

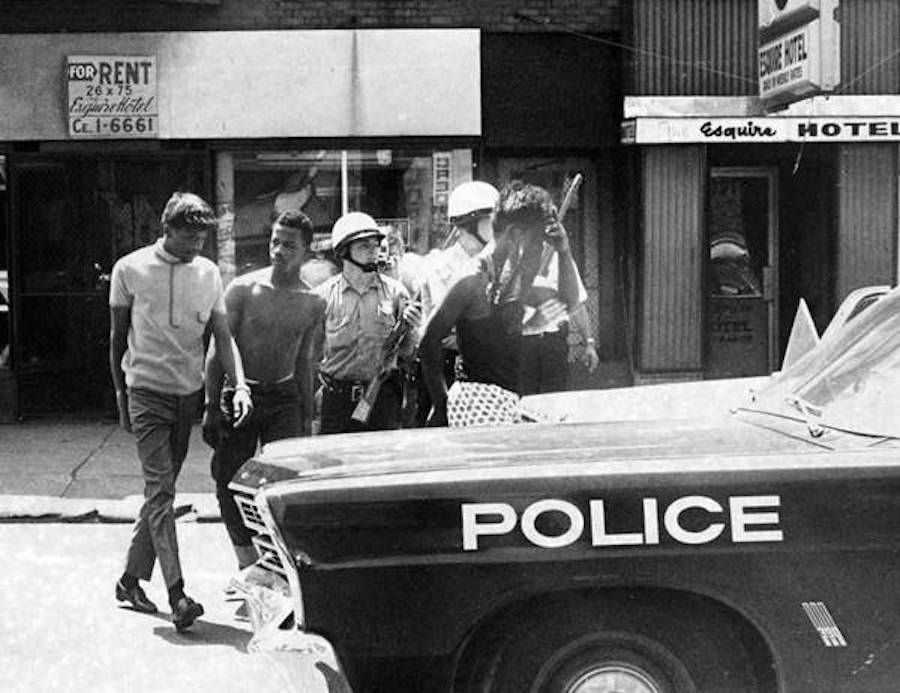

What happened next is where the various reports start to get muddled. The federal government’s report, written by Louis Masotti and Jerome Corsi (who today is famous for espousing right-wing conspiracy theories) asserted that it all began when two police department employees came to Glenville, just a few blocks from Evans’ home, to tow away a car that had been reported as abandoned. The two civilians, dressed in official uniforms, were fired upon from nearby homes by black nationalists. Armed policemen rushed to the scene. One officer later said, “This was the first time I’ve ever actually seen the beginning of a war.”

But according to Evans, the ambush came from police officers, not from his group. He was walking down the street, armed, when he heard the first shot, and saw one of the men in his group get hit by what he believed to be a submachine gun blast. While it’s clear that Evans was the epicenter of the violence, less clear is whether he was the cause, or simply happened to publicly arm himself and the other members of his group on the wrong night. Ultimately the local police decided Evans was the main person to blame.

As police officers infiltrated the three-block radius around Evans’ home to capture the black nationalists who were actively fighting back, the chaos only increased. “Reports included stories of police cornering and fondling black women in a local tavern, beating and shooting black men, and firing bullets in the black community that forced residents to stay home or duck for cover while on the streets,” Williams writes.

Longtime resident and activist Donald Freeman remembers being stunned by the mayhem as he walked home from work. “I could hear gunshots, I could see police cars and sirens, and there was a crowd of people that had gathered,” Freeman says in an interview with Smithsonian.com. He and others could only speculate as to how many people might be injured or killed, and what this would mean for the community.

Late in the evening of the 23rd, Evans emerged from a house, surrendering himself to the police. An eye-witness later said that Evans had tried to surrender multiple times throughout the evening in order to end the battle, but had been unable to reach the police. He was taken into custody, along with 17 other African-American men and women. Evans was eventually charged with first-degree murder for the seven slain, and three of the teenaged black nationalists were charged with first-degree murder, shooting to wound and possession of a machine gun.

The shootout and arrests led to another round of violence in Glenville in the coming days—something Mayor Stokes anticipated and tried to avoid. In a controversial move, Stokes made the unprecedented decision to pull out all white police officers and instead rely on community leaders and African-American officers to patrol the neighborhood on the following day, July 24. Though the action helped stem the bloodshed, Stokes “paid a terrific political price for being courageous enough to do that,” says Freeman. The mayor incurred the ire of the police force and lost much of the support he’d previously had from the city’s political establishment. He later struggled to move forward with his urban renewal programs, chose not to run for another term in 1971, and left Cleveland for a career in New York City.

As looting and arsons continued in the area, Stokes gave way to political pressure and ultimately called in the National Guard. Janice Eatman-Williams, who works at the Social Justice Institute at Case Western Reserve University, recalls seeing the National Guard tanks rolling down the street and worrying about family members who had to go outdoors to get to work. “The other thing I remember is what it smelled like once the flames were doused,” Eatman-Williams says. “You could smell burning food for several weeks after that.”

For Sherrie Tolliver, a historical reenactor and the daughter of the lawyer who represented Evans at trial, the memories are even more personal. “I was 11 years old, so for me it was shock and awe. I couldn’t process what it meant.” But she did have a sense that the case against Evans was unjust. In the aftermath, he faced charges of seven counts of first-degree murder, two for each of the three policemen killed and one for the civilian who died. Tolliver’s father, African-American lawyer Stanley Tolliver, who had previously worked with King, called it “legal lynching,” Sherrie says. “It failed to meet the standard by which you would prosecute and convict somebody of first-degree murder.”

At the trial, prosecutors argued Evans and the other members of the group amassed a cache of weapons, ammunition and first-aid kits in order to deliberately lead a rebellion. The defense team countered with their assertion that the violence was spontaneous, and that some of the police officers who were killed were intoxicated (one slain officer was found to be under the influence of alcohol). Nearly all the witnesses called were asked to testify about when Evans had bought weapons, and what his intentions with them were, rather than whether Evans actually did the shooting that resulted in the deaths.

At the end of the trial, Evans was sentenced to death by electric chair. But the Supreme Court ruled capital punishment unconstitutional during Evans’s appeal, and his sentence was reduced to life in prison. He died of cancer just ten years later, at age 46.

***

Reflecting on the event 50 years later, Tolliver is struck by how long it took her to grapple with the violence her community experienced. “We were all so transfixed with the Civil Rights Movement in the South, and the bombings and the firehoses. Those were the things we thought were in Mississippi and Alabama,” Tolliver says. “It wasn’t until I became an adult that I realized the same things happened here. Somebody shot through our house, and we got death threats.”

In her view, people who know about Glenville seem to have the opinion that it was instigated by troublemakers who wanted to kill white people. But the story was much more complicated than that. “It’s institutionalized. The black community is criminalized and then it’s penalized for being criminal,” she says.

Freeman agrees that the relationship between police officers and African-American communities is still strained, citing the 2012 shooting of Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams, both unarmed in their car, as one example. “Police in African-American neighborhoods, which are often called ghettos, have continued to function as an alien paramilitary force,” Freeman says.

But others hope that by more closely examining the history of the Glenville shootout, there may be opportunities for coming to terms with what happened. Eatman-Williams recently hosted a conference where community members could speak about their memories of the incident, and their hopes for the future, and documentary filmmaker Paul Sapin has been following Glenville High School students as they do their own research into the shootout. The teenagers have interviewed Glenville residents, visited libraries to do research, and even traveled to South Carolina to meet Louis Masotti, one of the authors of the official government report published on the Glenville shootout in 1969.

“In studying the past, they’re telling stories about their present and what they want to do to make changes for their future,” Sapin says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)