The Complicated Racial Politics of Going “Undercover” to Report on the Jim Crow South

How one journalist became black to investigate segregation and what that means today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/20/bd20daa7-754a-4037-8a5e-fd33b6287e3a/jimcrowindurhamnc.jpg)

In May 1948, Ray Sprigle traveled from Pittsburgh to Atlanta to rural Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee. He talked to sharecroppers and black doctors and families whose lives were torn apart by lynching. He visited desperately underfunded schools for black children and resort towns where only white people were allowed to bathe in the ocean. He spoke with scores of African-Americans, the introductions made by his travel companion, NAACP activist John Wesley Dobbs.

In one of the most striking moments of his reporting trip, he met the Snipes family—a black family forced to flee their home after their son was killed voting in a Georgia election. “Death missed [Private Macy Yost Snipes] on a dozen bloody battlefields overseas, where he served his country well,” Sprigle later wrote. “He came home to die in the littered door-yard of his boyhood home because he thought that freedom was for all Americans, and tried to prove it.”

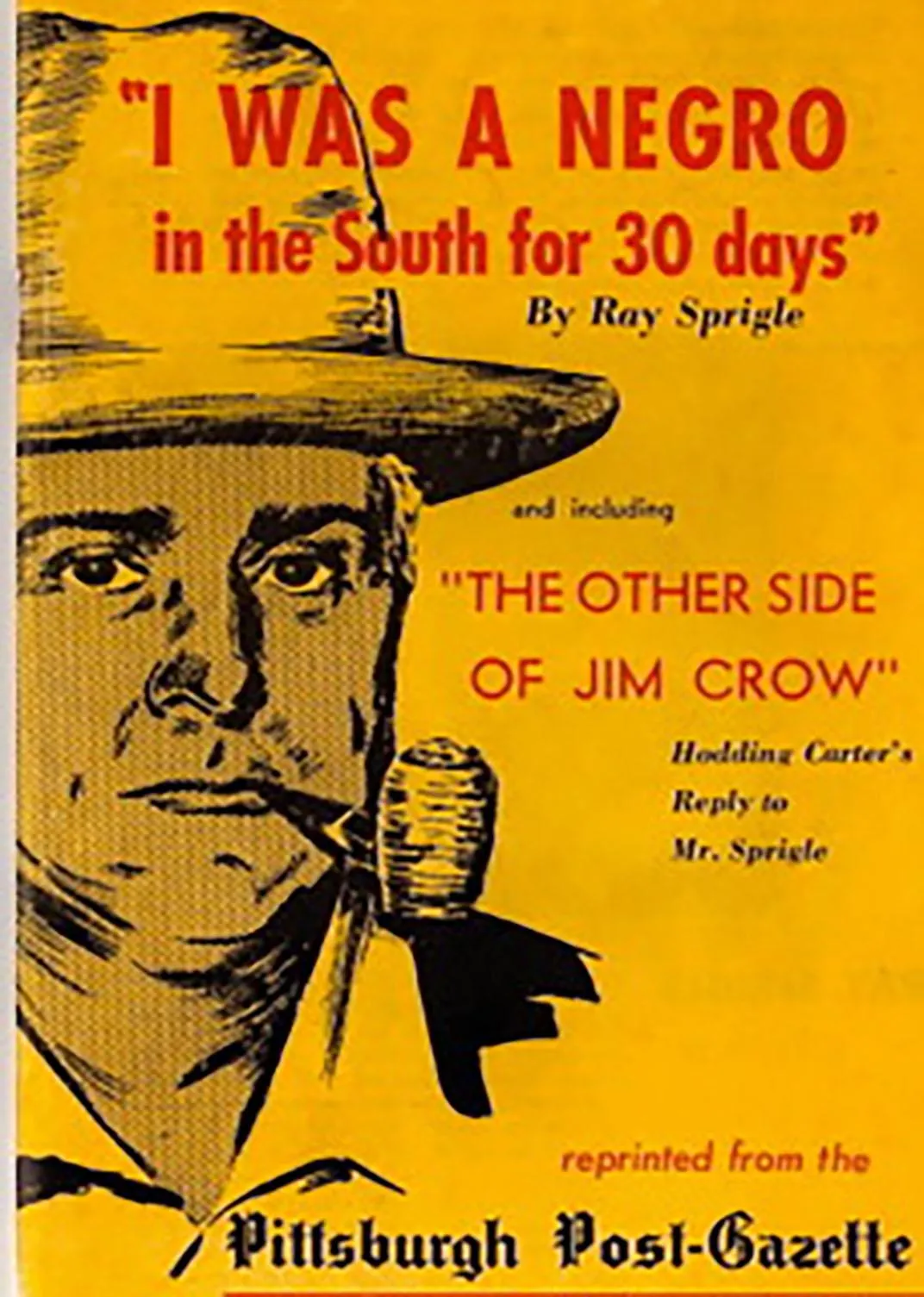

But Sprigle—a white, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist—wasn't traveling as himself. He traveled as James Rayel Crawford, a light-skinned black man with a shaved head who told his sources he was collecting information for the NAACP. More than a decade before John Howard Griffin undertook a similar feat and wrote about it in his memoir Black Like Me, Sprigle disguised himself as black in the Jim Crow South to write a 21-part series for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

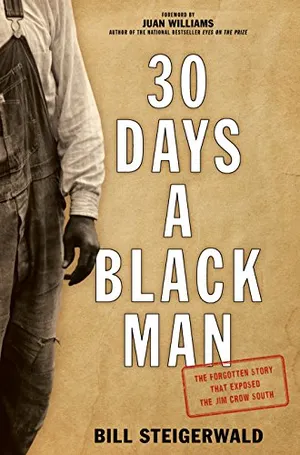

“Sprigle was so far ahead of the curve, his exploit was forgotten,” says Bill Steigerwald, himself a journalist who worked for years at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the author of a new book called 30 Days a Black Man. Steigerwald discovered the lengths Sprigle had gone to during his tour of the South 50 years after it happened. “I thought, oh my god, this is an unbelievable story, how come I’ve never heard of it? It was a great story about a journalist who had the whole country talking about race in 1948.”

Sprigle’s trip to the South wasn’t the first time he donned a disguise for the sake of a story. He’d previously launched undercover investigations of the Byberry mental institution in Philadelphia, a state-operated psychiatric institution called Mayview, and the black market for meat during World War II. Each of the investigations required he masquerade as someone he wasn’t—but none were as dramatic, or controversial, as his attempt to pass as African-American.

The act of “passing” was something Sprigle touched upon early in his series—though he described its prevalence in the African-American community. “The fact remains that there are many thousands of Negroes in the South who could ‘pass’ any day they wish,” Sprigle wrote. “I talked to scores of them. Nearly every one had a sister or brother or some other relative who was living as a white man or woman in the North.” Among the more famous examples of passing among the African-American community are Ellen Craft, who used her fair skin to escape slavery with her husband disguised as her servant in 1848, and Walter White, whose blond hair and blue eyes helped him travel through the Jim Crow South to report on lynchings for the NAACP. Far rarer were instances of white people passing as black, because such a transition meant giving up the benefits of their race. And Sprigle’s act wasn’t universally praised or accepted by other writers of the era.

“Mr. Sprigle is guilty of the common blunder of a great number of other northern whites. A white man who is sincerely interested in promoting the advancement of the Negro in the South need not make any apology for being white," a reviewer in the Atlanta Daily World, the city’s still-extant black newspaper, wrote. "And never once have we heard of them changing racial identity in order to accomplish their desired ends.” The sentiment was echoed in a review of Sprigle’s book, In the Land of Jim Crow. It was “somewhat doubtful whether a white, pretending to be a Negro” could really understand the experience of that group, the reviewer wrote.

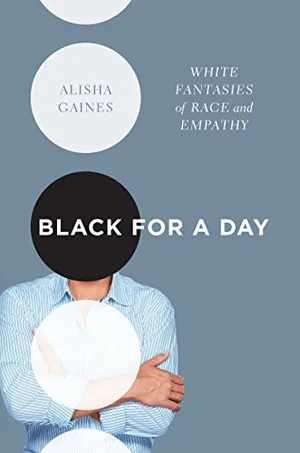

“It’s really easy to think, [Sprigle] is problematic, let’s dismiss everything,” says Alisha Gaines, professor at Florida State University whose forthcoming book Black for a Day: Fantasies of Race and Empathy deals with Sprigle and other cases of white-to-black passing. “I don’t advocate for everyone to go paint themselves and shave their heads, but there’s something about their intentionality that I want to hold on to. About wanting to understand, about caring enough and being compassionate.” But, Gaines adds, it seemed like Sprigle reported the story in disguise in an (unsuccessful) attempt at another Pulitzer rather than for reasons of social justice.

“In 4,000 miles of travel by Jim Crow train and bus and street car and by motor, I encountered not one unpleasant incident,” Sprigle concluded at the end of his series. “I took no chances. I was more than careful to be a ‘good [n****r.]’” What Sprigle clearly missed, however, was that behavior and caution had little to do with how blacks were treated in the South. Griffin, once he began publishing his expose in an African-American owned magazine, was forced to take his family and flee the country after receiving death threats and having an effigy of him hung in Dallas.

Gaines has also found, in studying men like Sprigle and Griffin, that engaging with racism on an interpersonal level is much different than recognizing it as a structural issue. Though Sprigle provided coverage of racism in the South, he failed to cover racism in the North. He mentioned the “injustice” of discrimination in the North in one report, but argued that the focus should be on the “bloodstained tragedy” of the South.

In Sprigle’s Pittsburgh, 40 percent of employers banned black employees outright, Steigerwald writes. There were no black doctors until 1948, only two black teachers in integrated schools, and numerous instances of segregation in public pools, theaters and hotels. But the white media seemed disinterested in covering that discrimination. “If they seriously cared about civil rights, institutionalized racial discrimination, or black workers being automatically shut out of most of the best jobs in their hometown because of their skin color, the white papers didn’t editorialize about it,” Steigerwald writes.

Steigerwald sees Sprigle as an unlikely hero who delivered harsh truths to an audience that wouldn't have been receptive of those same issues if delivered by an African-American reporter—and might never have seen those stories given the era’s segregated press. “It would’ve been nice if a black man could’ve pulled that off, but given the segregated media of the time, the greatest black writer of all could’ve written exactly what Sprigle wrote and about two white people would’ve seen it.”

But for Gaines, that’s just another effect of racism. “Black people have been writing about what it means to be black since 1763. At the end of the day, as well-meaning as I think some of these projects were, it is a project of white privilege,” Gaines says. “It’s a lack of racial navigation when a white person says, ‘I have to assume this authority in order for other white people to get it.’”

Gaines isn’t alone in the critique. CBS newscaster Don Hollenbeck praised In the Land of Jim Crow, but thought a black journalist “probably would’ve collected many times the material the Post-Gazette reporter did.” And while there were admittedly few African-American journalists working for major daily publications at the time, there was at least one: Ted Poston, who worked for the New York Post and, despite serious concerns for his safety, wrote about a rape trial in Florida in 1949, in which three African-American men were accused of raping a white housewife.

There were also a limited number of white southern journalists talking about issues of racism and injustice at the time. One of them was Hodding Carter Sr., the editor of the Democrat Delta-Times in Greenville, Mississippi, who was considered a liberal despite failing to condemn segregation. Still, Carter spoke out against the violence of lynching and the racial discrimination African-Americans faced. But by focusing on the South, Carter felt Sprigle was singling out the region for a problem that plagued all parts of America.

“[Sprigle] might disguise himself as a Mexican in the Southwest, or a Filipino or Japanese on the west coast, or a Jew in a good many American cities, or a militant, proselytizing Protestant in Boston, or a Negro in Chicago’s South Side, or a truly poor white in Georgia,” Hodding wrote, espousing what was essentially the “All Lives Matter” argument of its time. “He’d discover the really basic and menacing fact that prejudice isn’t directed solely to black skins or limited to the South.”

Sprigle’s work stirred up plenty of controversy and was never reprinted by white southern papers. But it did stimulate a national media debate about Jim Crow and racism. Both Steigerwald and Gaines agree that it’s a story worth discussing today—for different reasons.

“It shows how far we’ve come and maybe how far we haven’t come,” Steigerwald says. “If Ray Sprigle had worked for a New York newspaper and done all the things he did, by 1950 Spencer Tracy would’ve been playing him in a movie.”

For Gaines, the legacy is less about Sprigle’s journalistic prowess and more about how we understand his actions today. “I think it’s even more timely now because of our political climate and how to be a good ally. What does that mean, and what does empathy look like?” It doesn’t mean changing the color of one’s own skin anymore, Gaines says—but questioning the superiority of one’s whiteness is still a valuable lesson.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)