Rare Photos Chronicle an Early Castro Rally in Cuba

When Fidel Castro asked for a show of hands in support of his new policies, an American journalist captured the response

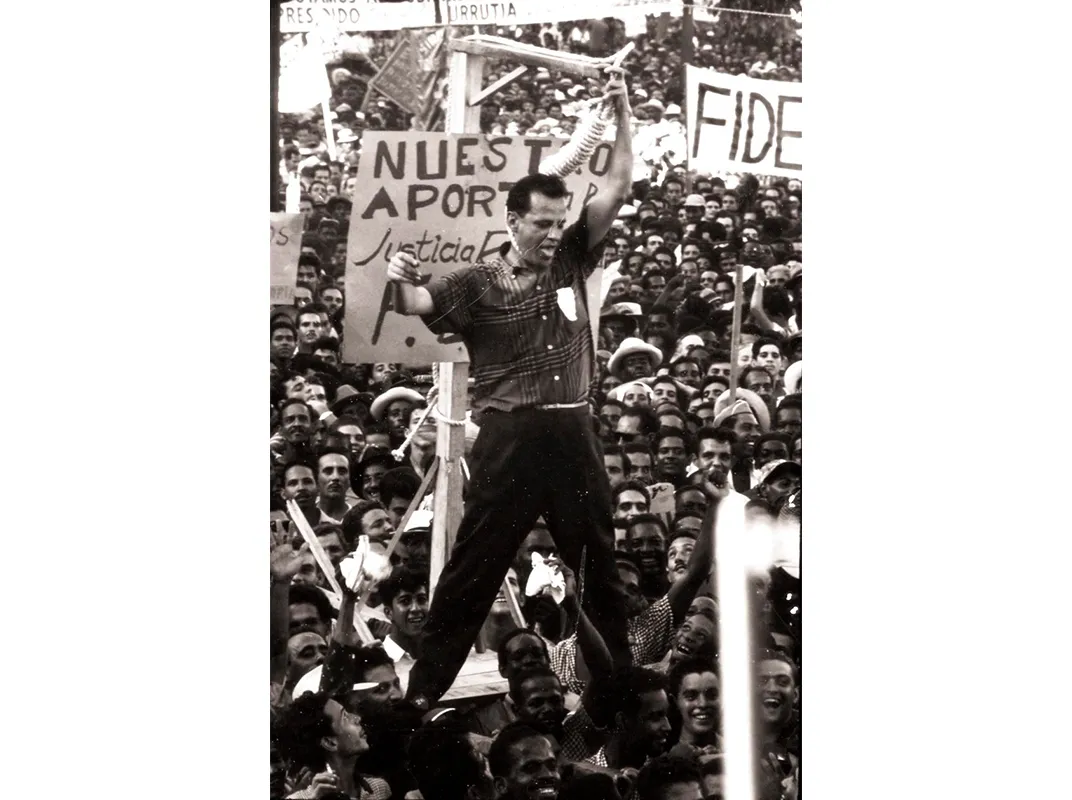

In Mid-January 1959, Fidel Castro and his comrades in revolution had been in power less than a month. Criticized in the international press for threatening summary justice and execution for many members of the government of ousted dictator Fulgencio Batista, Castro called on the Cuban people to show their support at a rally in front of Havana's presidential palace.

Castro, 32, wore a starched fatigue cap as he faced the crowd. With him were two of his most trusted lieutenants: Camilo Cienfuegos, unmistakable in a cowboy hat, and Ernesto (Che) Guevara in his trademark black beret. Castro's supporting cast would change over the years—Cienfuegos would die in an airplane crash nine months later and Guevara would be killed fomenting revolution in Bolivia in 1967—but Fidel would return to the plaza repeatedly for major speeches until illness forced him to withdraw from public life in 2006 and from the Cuban presidency this past February.

"It's during this rally that Fidel for the first time turns to the crowd and says, ‘If you agree with what we're doing, raise your hand,' " says Lillian Guerra, an assistant professor of Caribbean history at Yale University. Later, she says, Castro's calling for shows of hands at such rallies "became officially a substitute for electoral voting."

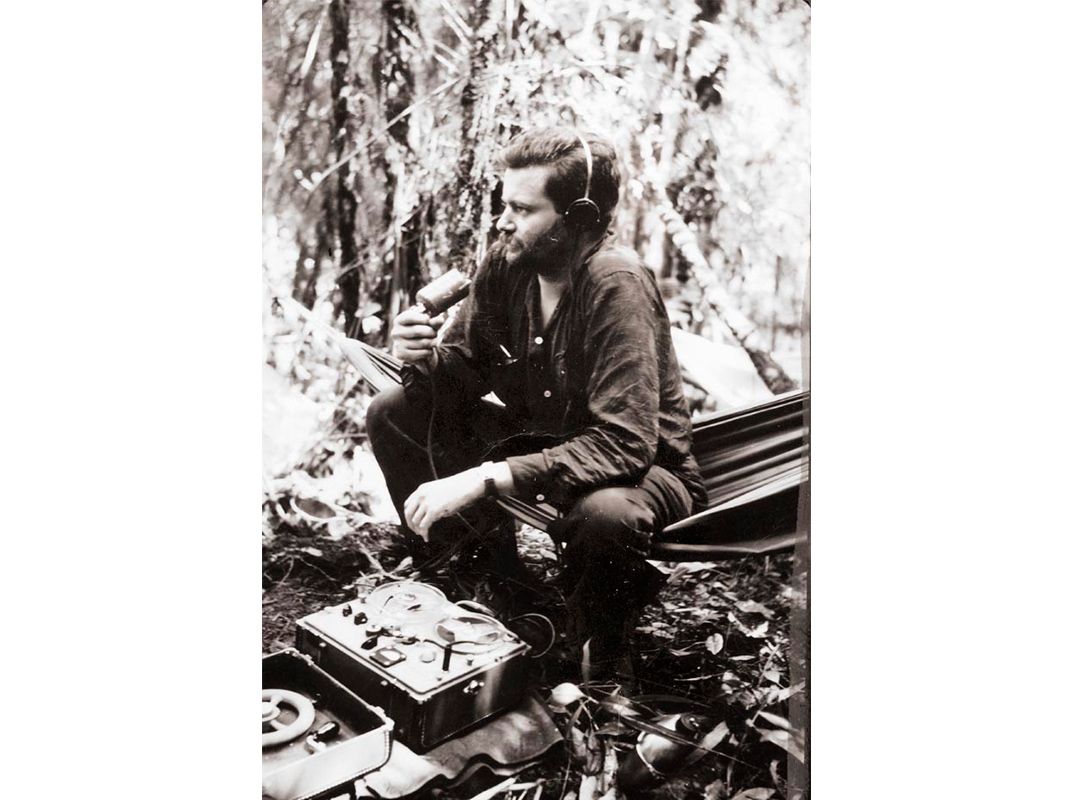

The event unfolds in a series of photographs taken by Andrew St. George, a writer and photographer who had chronicled the progress of Castro's revolution since 1957. St. George was a colorful character. Born in Hungary as Andras Szentgyorgyi, he had spent World War II helping opponents of the Nazis escape Budapest. Also an anti-communist, he went to Austria when the Soviets occupied Hungary after the war. In 1952 he immigrated to the United States and became a freelance journalist. He covered Cuba's revolution because he believed it was a nationalist—not a communist—uprising.

St. George died in 2001, at age 77; his widow, Jean, 80, is a film researcher who lives in Dobbs Ferry, New York. "I never thought my husband was a great photographer," she says matter-of-factly. But two years in Cuba had given him access that more accomplished photographers couldn't match. "And he took a lot of pictures," Jean St. George adds. "Some of them were bound to turn out."

St. George's images from that January rally—more than 100 of them—are included in a collection of contact sheets that he sold to Yale University in 1969 along with the rest of his Cuba oeuvre, more than 5,000 images. "We were always broke," Jean St. George says with a laugh. "So much of our lives were spent on expense accounts, so we could stay in great hotels and eat in great restaurants, but we couldn't pay the electric bill."

Yale paid $5,000 for the collection but had no funds to do anything with it, so it languished untouched for more than 35 years in the Yale Library. In 2006, Guerra helped secure a grant for more than $140,000 and led efforts to sort, digitize and catalog the photographs.

For Guerra, the New York-born child of Cuban parents, the collection represented a rich lode. The unedited pictures—of bearded guerrillas in the Sierra Maestra, ousted military officials on trial or a young, charismatic Castro—capture the excitement that gripped Cuba before the revolution's embrace of communism turned the country into a police state.

St. George's work "makes the Cuban revolution come alive," Guerra says. "What we get [in the United States] is so top-down—so much about what's wrong with Cuba. And in Cuba, the government encourages Cubans to believe they are in a constant state of war, with invasion from the United States threatened all the time."

But in January 1959, it all seemed new and somehow possible. In the contact sheets, the rally unfolds as the day goes on: a crowd gathers, demonstrators hold signs reading Impunidad—no! ("No mercy!") and Al paredón ("To the execution wall"). A university student wears a hangman's noose and a smile. The view over Castro's shoulder shows the multitude before him.

Castro "never believed he would get a million people to show up in the plaza," Guerra says. "He's really blown away. You see picture after picture of his face and the photographs of the crowd." After he asks for their support, Castro sees a forest of hands stretching to the sky. "Then there's this shot of Fidel's face," Guerra goes on. "He turns around, and he's surrounded by Che and Camilo and all the guys from the Sierra, and he gives them this look...‘We did it!' " For the first time, she says, "Fidel realized the visual dimensions of his power."

Within a year, however, St. George would become disillusioned with the revolution and return to the United States, where he reported on Cuban exiles plotting against the Castro government. Guevara ended up dismissing St. George as "the FBI guy," and he was routinely accused of being a CIA agent. His widow denies the charge. "He was Hungarian, so of course he was anti-communist," she says. "But he never worked for the CIA."

Guy Gugliotta covered Cuba for the Miami Herald in the 1980s.