Racism Kept Connecticut’s Beaches White Up Through the 1970s

By bussing black kids from Hartford to the shore, Ned Coll took a stand against the bigotry of “armchair liberals”

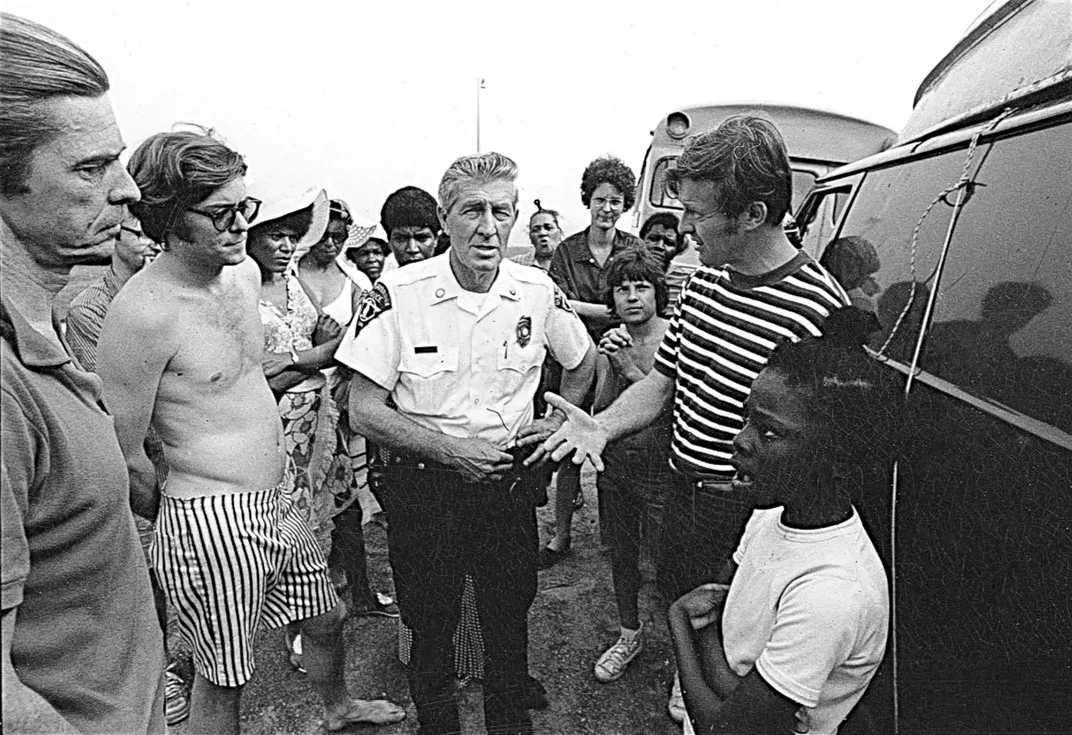

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6c/80/6c8063d3-c105-41ca-aa86-e2fd4e4d8b0f/kahrlfig03.jpg)

Lebert F. Lester II still remembers his first trip to the beach. It was the late 1970s, and he was 8 or 9 years old, the eighth in a family of 11 children from a poor and mostly African-American neighborhood in Hartford, Connecticut. The shore of Long Island Sound lay less than 40 miles away, but until that weekend Lester had only ever seen the ocean in books and on television.

“I was really excited,” Lester says, recalling how he and other kids from the neighborhood spilled out of their bus and rushed down to the water. They had been equipped with sand pails and shovels, goggles and life jackets—all donated by an anti-poverty organization that had organized the trip. Lester set to work building a sand castle, and he was soon joined by a young white girl who wanted to help.

“I’m talking to her about how we’re going to do it, we’re working together, and I’m not sure how long it was, but I look up and I see a man—I guess it was her daddy—and he snatches her away,” remembers Lester, recently reached by phone at his Hartford barbershop. Reasoning that it was simply time for the girl to go home, he kept on building. Then the girl came back. “She says I’m nice, why don’t I just go in the water and wash it off? I was so confused—I only figured out later she meant my complexion.”

It was his first experience with racism, but Lester still remembers that beach trip, and others that followed, as highlights of his childhood. And although they weren’t aware of their roles at the time, Lester and his friends were also part of a decade-long struggle for beach access—a campaign that aimed to lift what many called Connecticut’s “sand curtain.”

Launched by a white, self-avowed class warrior named Ned Coll in 1971, the effort unmasked the insidious nature of bigotry, especially in the supposedly tolerant Northeast, as well as the class and racial tensions that lurk beneath the all-American ideal of seaside summer vacations. It’s a story that still resonates today, argues University of Virginia historian Andrew Karhl in a new book, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline.

“Ned Coll was drawing attention to structural mechanisms of exclusion that operated outside of the most explicit forms of racism,” Kahrl says in an interview. While we still tend to associate racism with Ku Klux Klan marches and Jim Crow laws, racism also manifests more subtly, he explains, in ways that are often harder to fight. Coll saw the blatant and intentional segregation of his state’s beachfront, ostensibly public lands, as an egregious example of New England bigotry. “We think of beaches as wide-open spaces, and we associate them with freedom, but they have also been subject to very concerted efforts to restrict access, often along racial lines.”

The advent of private beach associations in Connecticut dates to the 1880s, when the state legislature granted a charter permitting certain forms of self-governance for a handful of rich families who owned vacation homes in the beach town of Old Saybrook. Commercial developers followed that same legal path during the first few decades of 20th century as they bought up farms and forestland along the coast and built vacation communities aimed at middle-class whites. These charters generally banned non-members from using parks, beaches and even streets, and associations enacted deed restrictions that prevented property from being sold to African-Americans or Jews.

Established towns were subtler in their efforts to keep out the masses. Kahrl notes that Westport, for example, declared parking near the beach a residents-only privilege in 1930, following that ordinance with one that banned non-residents from using the beach on weekends and holidays. These barriers were not explicitly aimed at people of color, but the effect was the same as Jim Crow laws in the South, especially since they were often unevenly enforced by local authorities. U.S. law declares “the sands below the high-tide line” to be public land, but by the 1970s, private property almost always stood between would-be beachgoers and the wet sand that was legally theirs.

A Hartford native like Lester, Ned Coll grew up the comfortable son of a middle-class Irish-American family. As in other northern states, segregation was not enforced by laws, but in practice; Hartford’s black and white communities were very separate. Coll, who was groomed for college and a stable white-collar career, might have easily lived his entire life in Hartford without setting foot in the predominantly African-American North End, where Lester grew up.

But the assassination of John F. Kennedy changed things. Inspired by the rhetoric of the martyred president and his brother Robert, Coll quit his insurance job in 1964 and founded Revitalization Corps, a volunteer-driven organization that provided tutoring, employment, mentorship and subsidies for residents of the North End (and later organized Lester’s trip to the beach). Coll opened a branch in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, and the concept soon spread to other cities as followers and admirers started their own Revitalization Corps chapters.

In addition to helping impoverished people with day-to-day needs, Coll used Revitalization Corps to confront what he saw as the complacency of white America—the people he referred to contemptuously as “armchair liberals.”

Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline

During the long, hot summers of the late 1960s and 1970s, one man began a campaign to open some of America’s most exclusive beaches to minorities and the urban poor.

“He understood, on an instinctual level, that the problem of racism was a problem of white people, and white people needed to solve it,” Kahrl says. “So he targeted these very liberal but passive communities that, on the one hand, talked the talk, but didn’t walk the walk, and so often actually made the problems worse.”

The long, hot urban summers of the 1960s and ’70s laid bare the unfairness of it all. While their well-off white counterparts enjoyed days at the beach or the pool, children living in tenements and housing projects were forced to get creative. “We got a wrench and we opened the fire hydrant,” Lester says. “You’d cut out both sides of a pork and bean can and use it as a funnel to direct the spray, and the kids would play until the fire department showed up.” Others tried to swim in polluted urban waterways, and the drowning deaths of poor African-American children were a seasonal tragedy.

But summer also had a symbolic value. In part because they are inextricably linked to social status, and because they require a certain level of undress that can inspire sexual panic, swimming pools and beaches have long been sites of racial anxiety.

“You will probably see, over the course of this summer, too, flash points over leisure and recreation,” says Kahrl, whose previous book, The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South, traced the rise and fall of black-owned shorefront in the 20th century.

His prediction has already come to pass: In June, a white man harassed a black woman and her daughter at a hotel pool in California, demanding to know if they had showered. Two weeks later, in South Carolina, a white woman was charged with assaulting a black teen who was visiting a neighborhood pool with his friends.

Coll believed the only way to fight racism was to confront it head-on. So, beginning in 1971, he recruited busloads of African-American and Latino children to break—by force if necessary—the color barrier that had long blocked them from Connecticut’s beaches. As Kahrl details in his book, the ensuing confrontations with quaint towns and posh beach clubs would make headlines throughout the 1970s.

When Revitalization Corps brought several busloads of children to Old Lyme, they were met with glares and epithets. At the private Madison Beach Club, Coll and 50 children staged an amphibious landing, planting an American flag in the wet sand as club members pulled their own kids away. In tony Greenwich, accompanied by a CBS News crew, Coll was arrested for trespassing. He arrived with North End children in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, and demanded an audience—eventually granted—with Senator Ted Kennedy.

As he worked to “free the beaches,” in the words of a protest sign Revitalization Corps children and volunteers often carried, white residents wrote to the governor accusing Coll of “bringing the ghetto” to the shore and “importing trouble.” Old money Yankees opined on the need to preserve privacy, while middle class whites complained to the newspaper that they had “worked for our right to own beach property.”

Outright violence was rare, although in Old Lyme someone assaulted a Revitalization Corps staffer and later burned down a cottage the organization was renting. Still, Lester says Coll and the parents and volunteers who came along to chaperone were always careful to protect the children, ensuring that their focus remained on having fun. And as the field trips drew attention to the nationwide issue of beach access, the war also played out in the courts, statehouses and even Congress.

The ultimate results were mixed, Kahrl argues in the book. Over time, through lawsuits, regulation and legislation, beaches in Connecticut and other states did become more publicly accessible. In 2001, the Connecticut Supreme Court unanimously affirmed non-residents’ rights to use town parks and beaches. Still, those who want to keep summer to themselves have found new ways to exclude people—high parking fees for nonresidents, for instance, are still in effect in many beach towns across the country.

“The biggest negative about trying to fight this battle is that it’s a seasonal effort, and over the winter people forget about it,” says Coll, now in his late 70s and in failing health, but eager as ever to take phone calls from the media. Revitalization Corps had faded by the early 1980s, and the beach trips are now a distant—if beloved—memory for many of the now-grown kids that boarded those buses back in the 1970s.

But Coll still hopes that one day Americans of every race and class will have equal access to the pleasures of a day at the seashore—and perhaps Kahrl’s book will jump-start the effort. “A lot of the shoreline question was about greed,” Coll says. “But people have to share summer.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/amy.png)