The Controversial Afterlife of King Tut

A frenzy of conflicting scientific analyses have made the famous pharaoh more mysterious than ever

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/6a/1d6a0212-312b-4fb4-b124-bce3e4fb8946/dec14_j10_tut.jpg)

The Valley of the Kings lies on a bend in the Nile River, a short ferry ride from Luxor. The valley proper is rocky and wildly steep, but a little farther north, the landscape gives way to gently rolling hills, and even the occasional copse of markh trees. It was here, in a humble mud-brick house, that the British Egyptologist Howard Carter was living in 1922, the year he unearthed the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamun, forever enshrining both the boy king and himself in the annals of history.

These days, the house serves as a museum, restored to its nearly original state and piled high with Carter’s belongings—a typewriter, a camera, a record player, a few maps, a handful of sun hats. Toward the back of the museum is a darkroom, and out front, facing the road, is a shaded veranda.

On the September day I visited, the place was empty, except for a pair of caretakers, Eman Hagag and Mahmoud Mahmoud, and an orange kitten that was chasing its own shadow across the tiled floor.

Most of the lights had been turned off to conserve electricity, and the holographic presentation about Carter’s discovery was broken. I asked Hagag how many visitors she saw in a day. She shrugged, and studied her hands. “Sometimes four,” she said. “Sometimes two. Sometimes none.”

Mahmoud led me outside, through a lush garden overhung with a trellis of tangled vines, and toward the entrance of what appeared to be a nuclear fallout shelter. An exact replica of Tutankhamun’s tomb, it had opened just a few months earlier, and Mahmoud was keen to show it off.

“We knew that tourism in the real tomb was having a disastrous effect—all that foot traffic, all that breath, all those hands,” Adam Lowe, the British artist whose company, Factum Arte, created the facsimile, told me. “We wanted to encourage a more responsible tourism before the decay progressed.”

The first step in creating the replica was closely studying the surfaces of the original tomb and then scanning every inch with laser and light devices as well as high-resolution photography—a process that took five weeks. The resulting data was taken to Madrid, where it was processed and used to precisely carve the surface of the tomb and other structures, which were covered by slightly elastic printed acrylic skins; artists fashioned the sarcophagus facsimile of hand-painted resin.

Lowe had originally hoped to open the exhibit in 2011, but the Egyptian revolution threw everything into chaos, and it wasn’t until 2013 that the pieces made their way to Luxor. Meanwhile, the number of visitors entering the Valley of the Kings dwindled significantly because of the threat of terrorism and political unrest.

Mahmoud predicted that soon there would be an upswing in tourism. “And then,” he said, hopefully, “the original tomb will close, and lots of people will come to us.” For now I was the only visitor. Mahmoud pointed at his favorite painting: a mural of 12 seated baboons, each representing a different hour of the night. Above the baboons, a scarab, here representing the coming dawn, sailed on a solar barque.

The detail was astonishing to behold. Not only had the murals been perfectly reproduced, so had the mottled spores of mold that grew on them. I ran my fingers through the grooved hieroglyphs on the sarcophagus and across a painting depicting Tut—his skin Frankenstein green—being welcomed into the afterlife.

Standing there, it was possible to feel one step closer to history, and to the young king whose life and apparently untimely death around 1323 B.C. continue to bedevil Egyptologists of all stripes. In that sense, advances in technology have brought us closer than ever to understanding who King Tut was. But in another, profound sense, three millennia after his death—and with a spate of philosophical and scientific arguments still roiling the field of Tut studies—we’ve never seemed further away.

“Tutankhamun has been a projection screen for theories for almost a hundred years,” the Egyptologist Salima Ikram, co-author of a key 2013 paper that sizes up a long century of Tut theorizing, told me over coffee in Cairo. “Some of that, frankly, is researchers’ egos. And some of it is our desire to explain the past. Look, we’re all storytellers at heart. And we’ve gotten very much addicted to telling stories about this poor boy, who has become public property.”

***

Egyptology has always been a game of conjecture—some of it well-rooted, and some of it decidedly not. As the protagonist of Arthur Phillips’ 2004 novel The Egyptologist writes of the bygone pharaohs, “these once-great men and women now cling to their hard-won immortality by the thinnest of filaments...while, across that chasm of time from them, historians and excavators struggle to build a rickety bridge of educated guesses for those nearly vanished heroes to cross.”

Since Howard Carter discovered the tomb now known as KV62, in 1922, no pharaoh has inspired more “educated guesses” than Tut. He probably came of age during the reign of Akhenaten, a ruler who famously broke from centuries of polytheistic tradition and encouraged the worship of a single deity: Aten, the sun. Born “Tutankhaten”—literally, “the living image of Aten”—Tut is thought to have become king at age 9, and ruled (likely with the help of advisers) until his death at 19 or 20.

Compared with the long reigns of powerful pharaohs such as Ramses II, Tut’s rule can seem insignificant. “Considering how much attention we pay to Tut,” said Chuck Van Siclen, an Egyptologist at the American Research Center in Egypt, “it’s as if you wrote a history of the presidents of the United States and devoted three long chapters to William Henry Harrison.”

Even so, it doesn’t take a Jungian analyst to understand why Tut has captured the world’s attention for so long. Egyptologists had long been forced to make do largely with scraps and fragments, but Tutankhamun’s tomb was found nearly intact and piled high with fantastical treasures. There was the absurdly beautiful burial mask, with its jutting false beard and coiled serpent, poised to strike. There were the rumors of the “curse” that had supposedly claimed the life of Carter’s deep-pocketed backer, Lord Carnarvon. And above all, there was the mystery of Tut’s death—he perished suddenly, it seems, and was placed in a tomb constructed for another king.

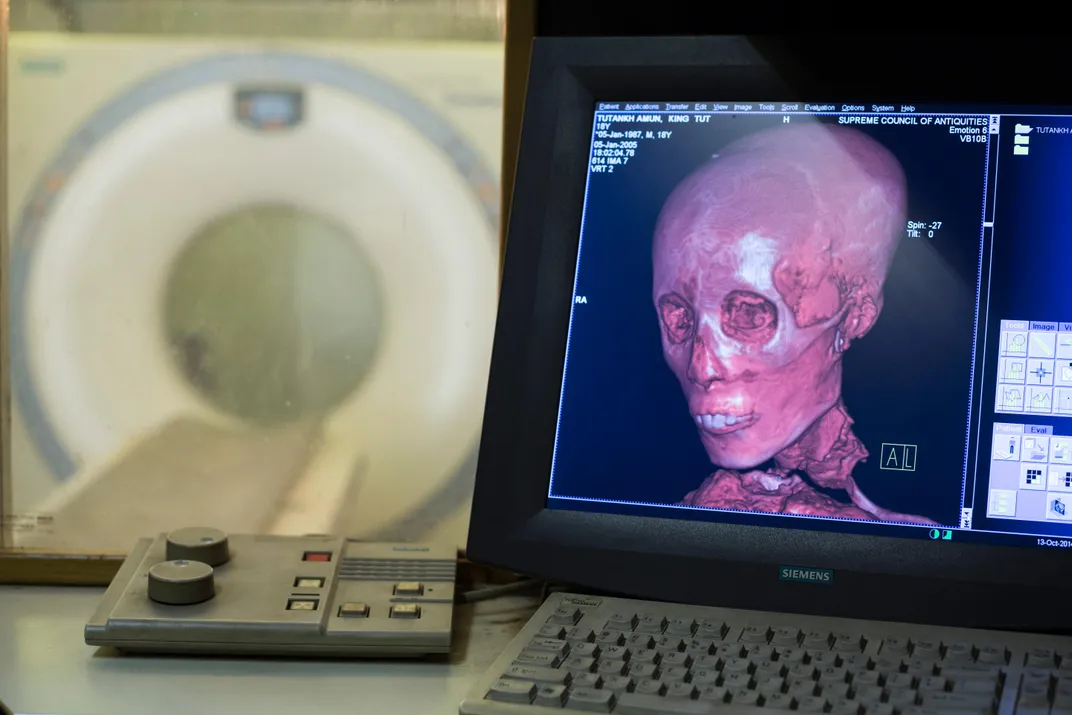

No one can be blamed for hoping that modern science, with its ever-increasing powers to reconstruct the past, would come to the rescue of this tantalizing mystery. The most recent phase of scientific Tut-ology began in 2005, when Zahi Hawass, then the head of the Egyptian antiquities service, used the latest technologies to study Egyptian mummies. He began with CT scans on a few royals at the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, in Cairo (a.k.a. the Egyptian Museum), before driving the CT scanner to Luxor, for a test on Tut himself.

He found the mummy in appalling condition. It had been interred in three coffins, which sat in the sarcophagus like Russian nesting dolls. Over time, resins and ointments used in the mummification process had congealed, sealing the two inner coffins together. Carter had employed increasingly violent maneuvers to remove the mummy from the coffins, and to get at the jewelry and amulets. First, the innermost coffin was left out in the sun to roast, in the hope that the heat would melt down the resins. Next, at Carter’s suggestion, an anatomist named Douglas Derry poured hot paraffin onto the mummy’s wrappings. Later, they pried the body out and yanked various limbs apart, and used a knife to slice the burial mask away from Tut’s head. Carter later reassembled the mummy as best he could (minus the mask and jewelry), and placed it in a wooden tray lined with sand, where it would remain.

Hawass was looking at a shriveled, broken thing. “It reminded me of an ancient monument lying in ruins in the sand,” he wrote. Still, he and his scientific co-workers walked the mummy, which reclined on the tray, out to the CT scanner.

Hawass soon returned to Cairo with roughly 1,700 CT images of Tutankhamun. There, they were examined by Egyptian scientists and three foreign consultants: the radiologist Paul Gostner; Eduard Egarter-Vigl, a forensic pathologist; and Frank Rühli, a paleopathologist based at the University of Zurich.

When Hawass announced the team’s findings, in March 2005, the banner revelation was that the free-floating bone shards in the skull, first documented during an X-ray scan in the 1960s, were probably not the result of a violent, perhaps murderous, blow to the head, as professional and amateur scholars had contended. In fact, the CT scans showed that one shard had come from the vertebrae, and another from an opening at the base of the skull. It appeared that embalmers had drilled a second hole in Tut’s head, a technique used in other royal mummifications.

So how had Tut died? Analyzing the CT scans, Hawass and his colleagues had found a fracture of the lower left femur. “This fracture,” the press release read, “appears different from the many breaks caused by Carter’s team: it has ragged rather than sharp edges, and there are two layers of embalming material present inside.” Perhaps Tutankhamun had been injured in battle or while hunting and the wound had become mortally infected, and he was mummified while the wound was still fresh. And thus the broken femur theory, splashed across newspapers and newscasts worldwide, came to be regarded as something close to fact.

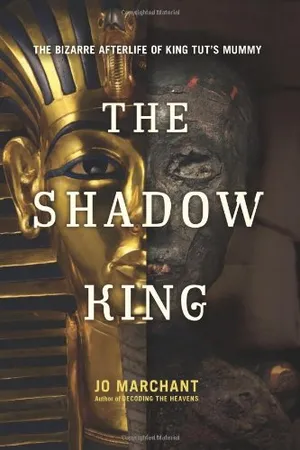

Yet two scientists who were present for the CT examination told me there was expert disagreement about the fracture at the time, with some arguing that it had led to Tut’s death and others arguing there wasn’t enough data to conclude that. As Jo Marchant notes in her 2013 book The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy, “interpreting the clues inside a three-thousand-year-old body isn’t easy, especially one that has been gutted by ancient embalmers, dismembered by modern archaeologists, and thrown about by looters.” Rühli initially believed that the leg fracture might have contributed to Tut’s death. But he has grown more skeptical of the idea. “I still think it’s the most likely diagnosis,” he told me in a Skype interview. “But eight or nine years have passed, and I’ve become much more experienced with the science. I’ve had a lot of time to think about how much pressure we were under.”

Of course, as Rühli suggested to me, it might be possible to settle the debate if he and other researchers were able to re-evaluate the CT scans. But Egyptian antiquities authorities have been stingy with the images—in 2005, none of the experts were allowed to take the entire data set home, for instance—and only a few of the 1,700 scans have been made public. The rest are controlled by Hawass and his coworkers.

I asked Hawass in an email when they planned on releasing the scans. He replied, “we are working to do that now.” He did not specify a date.

***

Returning to the Valley of the Kings, I went this time by the long bridge that connects Luxor proper with the West Bank. A shimmering, liquid light played over the sugar fields, and the sun, already damningly large, clung to the horizon. Guards in jellabiyas manned the checkpoints on the entry road, some clutching assault rifles, others rusted shotguns. The only other traffic consisted of donkey carts and skinny cattle that looked half-starved.

Soon, the taxi was hemmed in by the Theban Hills. Historians have long marveled at the manner in which the ancient Egyptians had managed to mold car-size chunks of rock into the Giza pyramids, or burrow deep into the earth to create the elaborate necropolis under the Valley of the Kings. To me it seemed equally incredible that the first Western archaeologists could arrive in these hills and even think they had a chance of getting inside. The cliffs and hills are fortresses—imposing, hard, impenetrable.

The taxi left me at the visitors center. After purchasing tickets, I rode a golf cart up a short gravel slope. In a shaded pavilion, a guide was delivering a lecture on Tutankhamun to a pair of sweat-sheened and clearly fatigued Australian women. “One year we think we know something for sure. The next year, they tell us, no, you’re completely wrong,” the guide said, frowning ruefully. “But that’s OK, I think. It’s OK to have a little mystery. And maybe we will never know what really happened to him. That would be OK, too.”

Of the dozens of tombs that honeycomb the Valley of the Kings, Tutankhamun’s is among the least impressive. It’s low-slung and cramped, and since all the treasure currently resides in the Egyptian Museum, in Cairo, there isn’t much to see in KV62, save for the murals and Tut himself. Still, the tomb remains the Valley of the King’s star tourist attraction.

I waited for a delegation of Russians, their heavy fanny packs sagging like ammunition belts, to exit, and made my move. Outside, the air was dry and crisp; inside it was cool and pleasantly damp. In the burial chamber, the caretaker handed me a flashlight and took his leave. Normally, a gate stops visitors from getting too close to the mummy, but the caretaker had left it open for me, and I squatted before the glass-topped case until I was eye level with the king.

He looked very small, as dead people often do. Death hollows us all out. Crystals dotted his feet, which were delicate and elfin—the feet of a child. His eyes were pitted, his teeth yellow and prominent, his mouth drawn back into a knowing smile.

A belief in eternal life after death was part of Tut’s religion. But the pharaoh could not have foreseen the afterlife he’d been saddled with: Decades of being poked and prodded and disassembled, passed through a CT scanner and X-ray machines, jabbed with biopsy needles. The subject of endless speculation. The butt of a thousand conspiracy theories.

Then again, perhaps it didn’t matter. I thought of something Gayle Gibson, an Egyptologist who teaches at the Royal Ontario Museum, had told me. “The Egyptians didn’t want to be forgotten,” she said. “They needed to be remembered. They wanted us to say their names, because to say the name of the dead is to make them live again. I don’t know if Tut can see us now, but I do know he certainly got his wish.”

***

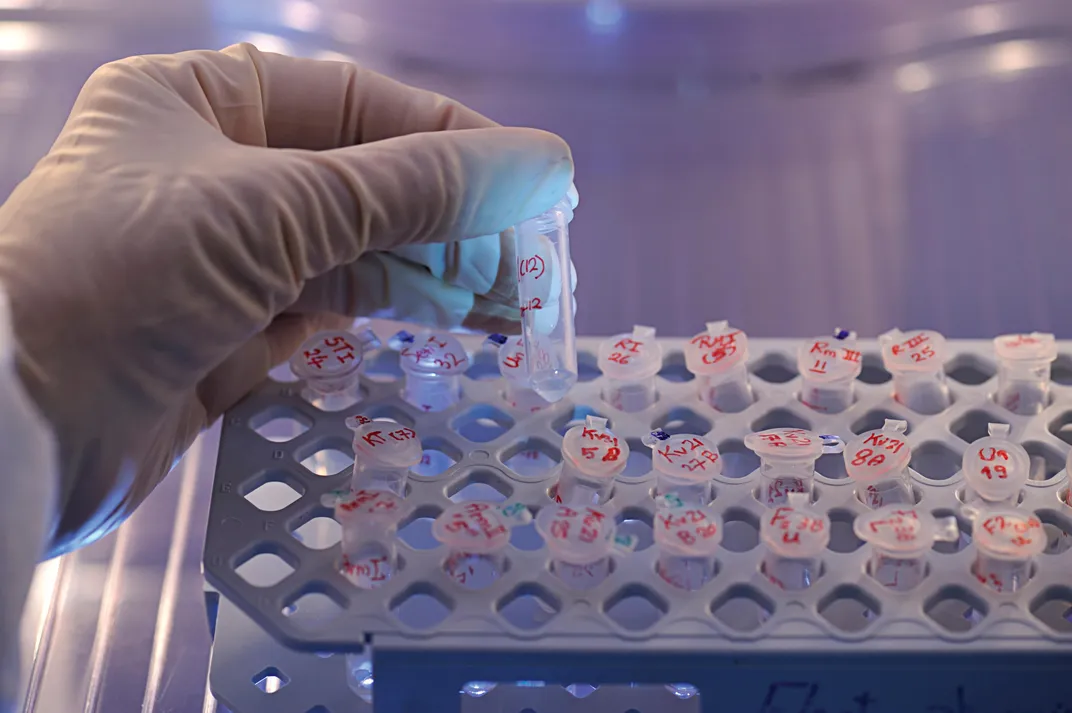

Hawass followed up the CT scans with a DNA test of the pharaoh and all the royals that might be related to him. For help, he turned to Yehia Gad, a molecular geneticist at the National Research Centre, in Cairo. The two men made for an unusual pair. Hawass, with his thick silver hair and ubiquitous fedora, was brash and loud, a showman at heart, while the bespectacled Gad was introverted and owlish; often, his words seemed to simply dissolve into a whisper.

In February of 2008, Hawass, Gad, a molecular geneticist named Somaia Ismail and a TV crew from the Discovery Channel, which was funding the study, traveled to Luxor to obtain samples from the mummy. Hawass stipulated that Gad, not any of the visiting scientists, would take the samples. “It’s our country,” Gad recalled to me. “Our ancestry. It made sense that it should be an Egyptian.”

Now, with the TV team close behind, Hawass’ delegation descended into the burial chamber of tomb KV62. The mummy lay faceup, staring at the murals that swirled across the ceiling.

Over the next three hours, using a green-handled biopsy needle, his face hidden by a green mask, Gad painstakingly removed the samples from inside the leg bones. The samples were packed in a sealed container, and Ismail and Gad took it by plane to Cairo. (“I’m absolutely sure I didn’t have one easy breath the entire flight,” Gad told me.) In the capital a multinational team of scientists set about extracting DNA from the samples and comparing it with DNA from ten other purportedly royal mummies. Among them were two unidentified female mummies found in the Valley of the Kings in tomb KV35, and a male mummy, found nearby in tomb KV55, that many believed belonged to Akhenaten, the so-called “heretic king” and the husband of Nefertiti.

Labs at the Egyptian Museum and Cairo University’s medical school processed the DNA. And two outside scientists—Carsten Pusch, of the University of Tübingen, and Albert Zink, of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman, in Italy—oversaw the study.

Hawass’ announcement of the findings in February 2010 coincided with the Discovery Channel’s documentary and a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA. The science was clear, Hawass said: There was almost a hundred percent chance that the male mummy in KV55—the mummy believed to be Akhenaten—was the father of Tutankhamun. The mother, meanwhile, was almost certainly one of the two females in tomb KV35—a woman, the tests showed, who appeared to be Akhenaten’s sister. In other words, Tutankhamun was the product of incest.

There was more. The researchers had found evidence of malaria tropica, a particularly cruel form of the mosquito-borne disease, in samples extracted from the Tut mummy. Hawass speculated that the effects of the malaria, combined with a degenerative bone condition, had killed Tutankhamun. Overnight, much of what had previously been known about Tut was dumped on its head. History was being rewritten.

“We did good, important work,” Hawass told me when I met him at his office in Cairo in September. “I was proud of it.” Hawass, after all the upheaval in the Egyptian government, is no longer director of antiquities, but he continues to write extensively. Last year, he published Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA, and a new volume will appear in 2015. Both books—as well as an unpublished paper, due next year, which he allowed me to read—stand steadfastly by the findings announced in 2010. “And I think that the story of King Tut, as we understand it now,” he said, “will remain as it is for 50 years, until a new generation comes, and new technology can appear.”

But critics of the research aren’t waiting. Eline Lorenzen, now a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and Eske Willerslev, director of the Centre for GeoGenetics in Denmark, voiced disbelief at the findings. “We question the reliability of the genetic data presented in this study and therefore the validity of the authors’ conclusions,” the two wrote in a letter to JAMA. “Furthermore, we urge a more critical assessment of the ancient DNA data in the context of DNA degradation and contamination.”

Others also pointed out that Carter and Derry had not exactly been gentle with the mummy; plenty of hands had touched it. So there was ample opportunity for Tut’s DNA (assuming any of it remained intact after 3,000 years) to become contaminated by DNA from other sources. Tom Gilbert, a scientist at the Centre for GeoGenetics, said he has misgivings about the DNA results from Tut. “You must find a way to deal with the contamination issue,” he said, “or else you’ve got nothing.”

An integral part of the 2010 study was the assertion that the mummy in KV55 was probably Akhenaten—an assertion that allowed Hawass to draw a direct line between one reign and the next. But that, too, has been challenged. The British osteoarchaeologist and forensic anthropologist Corinne Duhig, analyzing published X-rays of the mummy in KV55 and an osteological report by another scholar who had examined the specimen, concluded that the remains cannot belong to Akhenaten; instead, they are possibly those of another royal, the pharaoh Smenkhkare. “Whether the KV55 skeleton is that of Smenkhkare or some previously-unknown prince—and, sadly, recognizing that any proposed lineages leave us with new dilemmas in place of the old—the assumption that the KV55 bones are those of Akhenaten must be rejected before it becomes ‘received wisdom,’” Duhig wrote. In other words, Duhig strongly disputes the incestual ancestry that Hawass and co-workers announced to great fanfare.

As with the CT scans, debates centered on the DNA findings might be resolved by replicating the tests. Gad and Hawass seem reluctant to do so any time soon. Gad said they should “wait for a few years until the next generation sequencing technologies mature more. The team has waited more than 13 years to accomplish its dream of establishing the DNA lab, and the mummies have lain in their tombs for thousands of years. We can wait a little bit longer.”

But Zink, of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman, says the technology is ripe. He’s eager to do a “whole genome investigation of the royal mummies,” with the help of a next-generation DNA sequencer. The problem, he told me, is that it’s “unclear who’s responsible for the mummies now. Before, it was in the hands of Hawass. Now we’re stuck waiting for [Egypt] to agree on the permissions. Scientists are waiting for the system to become fully functional again.”

***

Born in Pakistan, educated in England and the States, Salima Ikram speaks in a crisp British accent that can sound antique in its phrasing—“in a jiffy,” she likes to say, and she described a colleague as “a very good chap” when we met at a café in central Cairo.

In the tightknit circles of Egyptology, where the loudest theories typically win the most attention, Ikram has developed a reputation as a quiet, skeptical objectivist. Last year, she and Rühli, the paleopathologist, published in a journal of human biology a paper titled “Purported Medical Diagnoses of Pharaoh Tutankhamun,” which meticulously dismembered decades of speculation about the king’s maladies.

Regarding the possibility that Tut had suffered from severe epilepsy—a hypothesis put forward by Hutan Ashrafian, a surgeon at Imperial College London, based on his close reading of murals and ancient texts and other sources—Ikram and Rühli were succinct: “There is no hard evidence to support this hypothesis.” Of the idea that Tut might have been done in by a horse kick to the chest, or by an injury sustained while handling a chariot, or by a furious “rogue hippopotamus” (proposals aired as recently as 2006), the scholars were dismissive: “Although all these dramatic ends to the king’s life are appealing, there remains little proof for these on his body or in the artifacts and texts from that time.” As for the role of malaria, an idea advanced by Hawass and colleagues, Ikram and Rühli said “the claim of malaria being a primary cause of death is disputed by various authors.”

Ikram and Rühli were more willing to entertain the argument that Tut suffered from syndromes affecting his feet. Famously, Tut was buried with more than 100 walking sticks and canes. And several paintings show him hunting in his chariot from a seated position. In their 2010 JAMA study, Hawass and co-authors had speculated, based on a reading of the CT scans, that Tut was afflicted by club foot or a similar disability in his left foot, as well as a disorder known as Köhler disease, which can cause pain and swelling and lead to a pronounced limp.

But Ikram wasn’t so sure. “I think part of what was interpreted as club foot could be due to the positioning of the foot during mummification—that could give an impression of distortion,” said Ikram, who, as it happened, was herself walking with a cane, troubled by a pelvis injury, sustained while working in Egypt’s western desert, and a knee ailment. Ikram has conducted experiments in mummifying rabbits, sheep and cats, and in many cases, she said, “bones don’t break, but they certainly curve.”

In addition to the murals depicting Tut sitting in a chariot, she pointed out, there are paintings in which he was standing. “You can’t pick and choose your evidence,” she said. (In a separate conversation, Yasmin el-Shazly, a scholar at the Egyptian Museum, concurred. “Ancient artwork can be symbolic, or it can be exaggerated in ways that we don’t yet fully understand. It’s dangerous to read it all as realism,” el-Shazly told me.)

I asked Ikram how she thought history would judge Hawass’ contributions to Tut studies. “I think it’s a wonderful thing that Zahi Hawass became interested in mummies,” she said, carefully. “And it’s a marvelous thing that he acquired the CT scan machine, and instigated so much research.” She arched her eyebrows. “And I think that if all the data is made publicly available, it would be a great service.”

On the taxi ride through Cairo back to my hotel, I reread Ikram and Rühli’s paper on my smartphone. I was struck by its emphatic conclusion. “As time progresses and medical technology improves, tests might be developed that could be carried out on soft tissue that might indicate the presence of diseases that leave no sign on bones—perhaps even a viral disease such as influenza. However, even with the best medical and Egyptological forensic work, it is doubtful that all aspects of Tut’s health and possible causes for his death will ever be known.”

***

The Egyptian Museum forms the northern border of Tahrir Square, ground zero for the 2011 revolution. Opened in 1902, the building is elegant, in a colonial way, but 112 years on, wind and soot and sand have taken their toll—the exterior looks increasingly like the artifacts it was designed to hold. Four years ago, during the height of the protests, looters dropped in through the roof and made off with 50-odd precious artifacts, apparently damaging a pair of mummies in the process. Thirty-six artifacts have been recovered, and the museum is now fully open again, although the crowds are anemic. One day this fall, two armored trucks full of troops were parked outside the front gate, and in the yard, an unofficial army of museum guides was shouting offers at passing tourists. “Ten dollars,” said a young man in a flame-red U2 shirt. “Fine, eight dollars. A full tour! Six dollars.” Finally, with a dose of good humor, he relented: “What about a million dollars?”

Mahmoud el-Halwagi, the institution’s director general, is slight and balding, with the mannered voice of a man who spends a lot of time in museums. Previously, he was the chief curator of relics from the Old Kingdom, an era that predated Tut. But he is accustomed to answering questions about the boy king. “In this line of work,” he said, “you can’t escape him.”

We climbed to the second floor, where the treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb are held. Late-afternoon light leaked through the windows, illuminating not only the carved graffiti on the wood railings—the Chicago Bulls logo, “I love you Amina,” SpongeBob—but also the fingerprints and palm marks that covered the glass display cases. El-Halwagi paused to wipe some away with a handkerchief.

The nation’s museum system was in the midst of an important transition, he said. In 2012, construction crews had finally begun work on the Grand Egyptian Museum, a new complex in the suburb of Giza, near the pyramids. The much-delayed project, which will cost well over half a billion dollars to build, is to open in August 2017. The Egyptian Museum on Tahrir Square will remain, but the real crowd-pleasers, like the Tut collection, will be moved to Giza.

“This will be the last to go,” El-Halwagi added, stopping in front of Tutankhamun’s famous golden mask. Seeing it up close is not unlike viewing the Giza pyramids or the Taj Mahal—no matter how much you’ve prepared yourself for the moment, the reality outstrips your expectations. Not because the object is more magnificent than you expected (although it is), but because its beauty is of a kind that feels incongruous with its history. How could something so perfect have been fashioned over 3,000 years ago? Judging by the slack-jawed scrum of visitors that surrounded the case displaying the mask, I wasn’t alone in that sentiment. “You can’t keep this away from people for too long,” el-Halwagi told me. “They go crazy.”

Before coming to the museum, I’d read about a new dispute over the Tut mummy, which the Supreme Council of Antiquities wanted to move to Cairo, apparently for a “checkup,” and possible further tests, which, if recent history is any indication, won’t necessarily bring scholars closer to the truth. But local and international Egyptologists denounced the plans—the mummy is far too delicate to be transported, they argued—and in late September, Mamdouh el-Damaty, the new antiquities minister, backtracked on the project.

I asked el-Halwagi whether he thought Tut’s mummy would ever leave his tomb. “Why not keep him where he is?” he said. “The man has been through enough.”

Related Reads

The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy