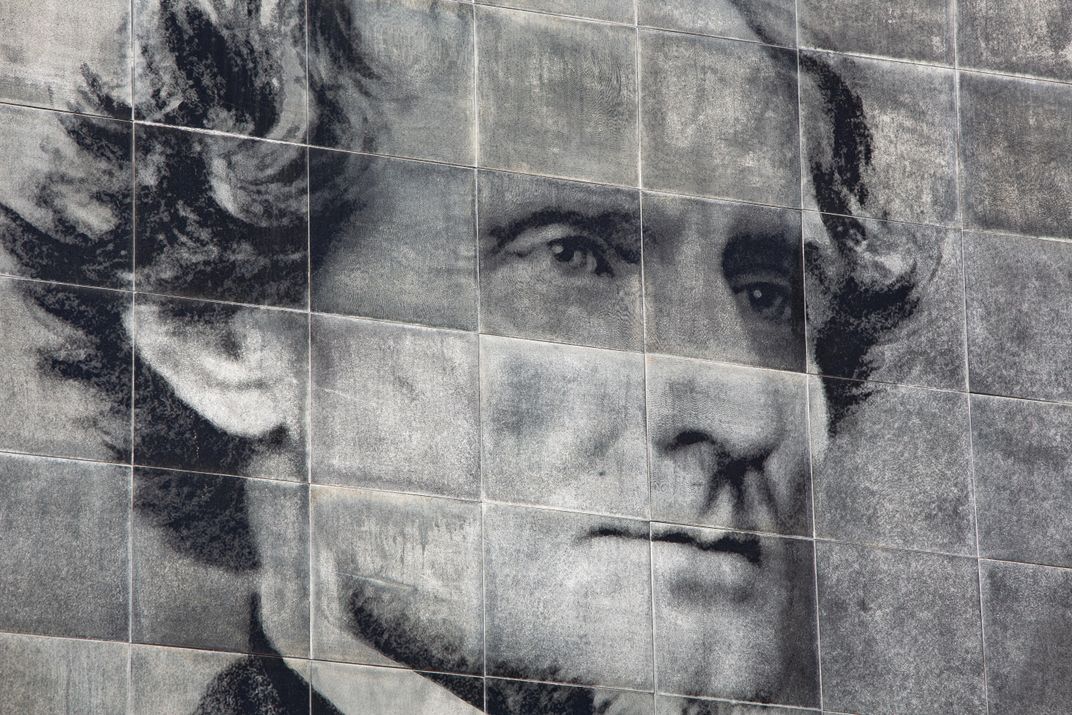

With centuries-old trees, manicured lawns, a tidy cemetery and a babbling brook, the Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library is a marvelously peaceful, green oasis amid the garish casinos, T-shirt shops and other tourist traps on Highway 90 in Biloxi, Mississippi.

One gray October morning, about 650 local schoolchildren on a field trip to Beauvoir, as the home is called, poured out of buses in the parking lot. A few ran to the yard in front of the main building to explore the sprawling live oak whose lower limbs reach across the lawn like massive arms. In the gift shop they perused Confederate memorabilia—mugs, shirts, caps and sundry items, many emblazoned with the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia.

It was a big annual event called Fall Muster, so the field behind the library was teeming with re-enactors cast as Confederate soldiers, sutlers and camp followers. A group of fourth graders from D’Iberville, a quarter of them black, crowded around a table heaped with 19th-century military gear. Binoculars. Satchels. Bayonets. Rifles. A portly white man, sweating profusely in his Confederate uniform, loaded a musket and fired, to oohs and aahs.

A woman in a white floor-length dress decorated with purple flowers gathered a group of older tourists on the porch of the “library cottage,” where Davis, by then a living symbol of defiance, retreated in 1877 to write his memoir, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. After a discussion of the window treatments and oil paintings, the other visitors left, and we asked the guide what she could tell us about slavery.

Sometimes children ask about it, she said. “I want to tell them the honest truth, that slavery was good and bad.” While there were some “hateful slave owners,” she said, “it was good for the people that didn’t know how to take care of themselves, and they needed a job, and you had good slave owners like Jefferson Davis, who took care of his slaves and treated them like family. He loved them.”

The subject resurfaced the next day, before a mock battle, when Jefferson Davis—a re-enactor named J.W. Binion—addressed the crowd. “We were all Americans and we fought a war that could have been prevented,” Binion declared. “And it wasn’t fought over slavery, by the way!”

Then cannons boomed, muskets cracked, men fell. The Confederates beat back the Federals. An honor guard in gray fired a deafening volley. It may have been a scripted victory for the Rebels, but it was a genuine triumph for the racist ideology known as the Lost Cause—a triumph made possible by taxpayer money.

We went to Beauvoir, the nation’s grandest Confederate shrine, and to similar sites across the Old South, in the midst of the great debate raging in America over public monuments to the Confederate past. That controversy has erupted angrily, sometimes violently, in Virginia, North Carolina, Louisiana and Texas. The acrimony is unlikely to end soon. While authorities in a number of cities—Baltimore, Memphis, New Orleans, among others—have responded by removing Confederate monuments, roughly 700 remain across the South.

To address this explosive issue in a new way, we spent months investigating the history and financing of Confederate monuments and sites. Our findings directly contradict the most common justifications for continuing to preserve and sustain these memorials.

First, far from simply being markers of historic events and people, as proponents argue, these memorials were created and funded by Jim Crow governments to pay homage to a slave-owning society and to serve as blunt assertions of dominance over African-Americans.

Second, contrary to the claim that today’s objections to the monuments are merely the product of contemporary political correctness, they were actively opposed at the time, often by African-Americans, as instruments of white power.

Finally, Confederate monuments aren’t just heirlooms, the artifacts of a bygone era. Instead, American taxpayers are still heavily investing in these tributes today. We have found that, over the past ten years, taxpayers have directed at least $40 million to Confederate monuments—statues, homes, parks, museums, libraries and cemeteries—and to Confederate heritage organizations.

For our investigation, the most extensive effort to capture the scope of public spending on Confederate memorials and organizations, we submitted 175 open records requests to the states of the former Confederacy, plus Missouri and Kentucky, and to federal, county and municipal authorities. We also combed through scores of nonprofit tax filings and public reports. Though we undoubtedly missed some expenditures, we have identified significant public funding for Confederate sites and groups in Mississippi, Virginia, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina and Tennessee.

In addition, we visited dozens of sites, to document how they represent history and, in particular, slavery: After all, the Confederacy’s founding documents make clear that the Confederacy was established to defend and perpetuate that crime against humanity.

(Listen to an episode of Reveal, from The Center for Investigative Reporting, about this special reporting project.)

A century and a half after the Civil War, American taxpayers are still helping to sustain the defeated Rebels’ racist doctrine, the Lost Cause. First advanced in 1866 by a Confederate partisan named Edward Pollard, it maintains that the Confederacy was based on a noble ideal, the Civil War was not about slavery, and slavery was benign. “The state is giving the stamp of approval to these Lost Cause ideas, and the money is a symbol of that approval,” Karen Cox, a historian of the American South at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, said of our findings. “What does that say to black citizens of the state, or other citizens, or to younger generations?”

The public funding of Confederate iconography is also troubling because of its deployment by white nationalists, who have rallied to support monuments in New Orleans, Richmond and Memphis. The deadly protest in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, where a neo-Nazi rammed his car into counter-protesters, killing Heather Heyer, was staged to oppose the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue. In 2015, before Dylann Roof opened fire on a Bible study group at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, killing nine African-Americans, he spent a day touring places associated with the subjugation of black people, including former plantations and a Confederate museum.

“Confederate sites play to the white supremacist imagination,” said Heidi Beirich, who leads the Southern Poverty Law Center’s work tracking hate groups. “They are treated as sacred by white supremacists and represent what this country should be and what it would have been” if the Civil War had not been lost.

* * *

Like many of the sites we toured across the South, Beauvoir is privately owned and operated. Its board of directors is made up of members of the Mississippi division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a national organization founded in 1896 and limited to male descendants of “any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate armed forces.” The board handles the money that flows into the institution from visitors, private supporters and taxpayers.

The Mississippi legislature earmarks $100,000 a year for preservation of Beauvoir. In 2014, the organization received a $48,475 grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency for “protective measures.” As of May 2010, Beauvoir had received $17.2 million in federal and state aid related to damages caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. While nearly half of that money went to renovating historic structures and replacing content, more than $8.3 million funded construction of a new building that contains a museum and library.

When we visited, three times since the fall of 2017, the lavishly appointed library displayed the only acknowledgment of slavery that we could find at the entire 52-acre site, though Davis had owned dozens of black men, women and children before the war: four posters, which portrayed the former slaves Robert Brown, who continued to work for the Davis family after the war, and Benjamin and Isaiah Montgomery, a father and son who were owned by Jefferson’s elder brother, Joseph. Benjamin eventually purchased two of Joseph’s plantations.

The state Department of Archives and History says the money the legislature provides to Beauvoir is allocated for preservation of the building, a National Historic Landmark, not for interpretation. Beauvoir staff members told us that the facility doesn’t deal with slavery because the site’s state-mandated focus is the period Davis lived there, 1877 to 1889, after slavery was abolished.

But this focus is honored only in the breach. The museum celebrates the Confederate soldier in a cavernous hall filled with battle flags, uniforms and weapons. Tour guides and re-enactors routinely denied the realities of slavery in their presentations to visitors. Fall Muster, a highlight of the Beauvoir calendar, is nothing if not a raucous salute to Confederate might.

Thomas Payne, the site’s executive director until this past April, said in an interview that his goal was to make Beauvoir a “neutral educational institution.” For him, that involved countering what he referred to as “political correctness from the national media,” which holds that Southern whites are “an evil repugnant group of ignorant people who fought only to enslave other human beings.” Slavery, he said, “should be condemned. But what people need to know is that most of the people in the South were not slave owners,” and that Northerners also kept slaves. What’s more, Payne went on, “there’s actually evidence where the individual who was enslaved was better off physically and mentally and otherwise.”

The notion that slavery was beneficial to slaves was notably expressed by Jefferson Davis himself, in the posthumously published memoir he wrote at Beauvoir. Enslaved Africans sent to America were “enlightened by the rays of Christianity,” he wrote, and “increased from a few unprofitable savages to millions of efficient Christian laborers. Their servile instincts rendered them contented with their lot....Never was there a happier dependence of labor and capital upon each other.”

That myth, a pillar of the Lost Cause, remains a core belief of neo-Confederates, despite undeniable historic proof of slavery’s brutality. In 1850, the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had escaped slavery, said, “To talk of kindness entering into a relation in which one party is robbed of wife, of children, of his hard earnings, of home, of friends, of society, of knowledge, and of all that makes this life desirable is most absurd, wicked, and preposterous.”

* * *

A few miles off the highway between Montgomery and Birmingham, past trailer homes and cotton fields, are the manicured grounds and arched metal gateways of Confederate Memorial Park. The state of Alabama acquired the property in 1903 as an old-age home for Confederate veterans, their wives and their widows. After the last residents died, the park closed. But in 1964, as civil rights legislation gained steam in Washington, Alabama’s all-white legislature revived the site as a “shrine to the honor of Alabama’s citizens of the Confederacy.”

The day we visited, 16 men in Confederate uniforms drilled in the quiet courtyards. Two women in hoop skirts stood to the side, looking at their cellphones. Though Alabama state parks often face budget cuts—one park had to close all its campsites in 2016—Confederate Memorial Park received some $600,000 that year. In the past decade, the state has allocated more than $5.6 million to the site. The park, which in 2016 served fewer than 40,000 visitors, recently expanded, with replica Civil War barracks completed in 2017.

The museum in the Alabama park attempts a history of the Civil War through the story of the common Confederate soldier, an approach that originated soon after the war and remains popular today. It is tragic that hundreds of thousands of young men died on the battlefield. But the common soldier narrative was forged as a sentimental ploy to divert attention from the scalding realities of secession and slavery—to avoid acknowledging that “there was a right side and a wrong side in the late war,” as Douglass put it in 1878.

The memorial barely mentions black people. On a small piece of card stock, a short entry says “Alabama slaves became an important part of the war’s story in several different ways,” adding that some ran away or joined the Union Army, while others were conscripted to fight for the Confederacy or maintain fortifications. There is a photograph of a Confederate officer, reclining, next to an enslaved black man, also clad in a uniform, who bears an expression that can only be described as dread. Near the end of the exhibit, a lone panel states that slavery was a factor in spurring secession.

These faint nods to historical fact were overpowered by a banner that spanned the front of a log cabin on state property next to the museum: “Many have been taught the war between the states was fought by the Union to eliminate Slavery. THIS VIEW IS NOT SUPPORTED BY THE HISTORICAL EVIDENCE....The Southern States Seceded Because They Resented the Northern States Using Their Numerical Advantage in Congress to Confiscate the Wealth of the South to the Advantage of the Northern States.”

The state has a formal agreement with the Sons of Confederate Veterans to use the cabin as a library. Inside, books about Confederate generals and Confederate history lined the shelves. The South Was Right!, which has been called the neo-Confederate “bible,” lay on a table. The 1991 book’s co-author, Walter Kennedy, helped found the League of the South, a self-identified “Southern nationalist” organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center has classified as a hate group. “When we Southerners begin to realize the moral veracity of our cause,” the book says, “we will see it not as a ‘lost cause,’ but as the right cause, a cause worthy of the great struggle yet to come!”

A spokeswoman for the Alabama Historical Commission said she could not explain how the banner on the cabin had been permitted and declined our request to interview the site’s director.

Alabama laws, like those in other former Confederate states, make numerous permanent allocations to advance the memory of the Confederacy. The First White House of the Confederacy, where Jefferson Davis and his family lived at the outbreak of the Civil War, is an Italianate mansion in Montgomery adjacent to the State Capitol. The state chartered the White House Association of Alabama to run the facility, and spent $152,821 in 2017 alone on salaries and maintenance for this monument to Davis—more than $1 million over the last decade—to remind the public “for all time of how pure and great were southern statesmen and southern valor.” That language from 1923 remains on the books.

* * *

An hour and a half east of Atlanta by car lies Crawfordville (pop. 600), the seat of Taliaferro County, a majority black county with one of the lowest median household incomes in Georgia. A quarter of the town’s land is occupied by the handsomely groomed, 1,177-acre A.H. Stephens State Park. Since 2011 state taxpayers have given the site $1.1 million. Most of that money is spent on campsites and trails, but as with other Confederate sites that boast recreational facilities—most famously, Stone Mountain, also in Georgia—the A.H. Stephens park was established to venerate Confederate leadership. And it still does.

Alexander Hamilton Stephens is well known for a profoundly racist speech he gave in Savannah in 1861 a month after becoming vice president of the provisional Confederacy. The Confederacy’s “foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.”

That speech was nowhere in evidence during our visit to the park. It wasn’t in the Confederate museum, which was erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy with the support of the state of Georgia in 1952 and displays Confederate firearms and uniforms. It wasn’t among the printed texts authored by Stephens that are placed on tabletops in the former slave quarters for visitors to peruse. And it wasn’t in the plantation house, called Liberty Hall.

Our guide, a state employee, opened the door of a small two-room cabin once occupied by Harry and Eliza—two of the 34 people Stephens held in bondage. The guide pointed to a photograph of the couple on a wall and said Stephens “kept them good, and took care of the people who worked for him.” We went on many tours of the homes of the Confederacy’s staunchest ideologues, and without exception we were told that the owners were good and the slaves were happy.

After the war, Stephens spent a great deal of energy pretending he wasn’t entirely pro-slavery, and he returned to public life as a member of Congress and then as governor. Robert Bonner, a historian at Dartmouth who is at work on a biography of Stephens, said the Stephens memorial maintains the fraud: “The story at Liberty Hall is a direct version of the story Stephens fabricated about himself after the war.”

Half an hour away is the home of Robert Toombs, the Confederacy’s secretary of state and Stephens’ close friend. His house has been recently restored, with state as well as private funds, and Wilkes County has taken over daily operations. In a ground-floor gallery, posters in gilt frames hang below banners that announce the four acts of Toombs’ life: “The Formative Years,” “The Baron of Wilkes County,” “The Premier of the Confederacy” and “Without a Country.” About slavery, nothing.

When asked about that, the docent, a young volunteer, retrieved a binder containing a Works Progress Administration oral history given by Alonza Fantroy Toombs. It begins, “I’se the proudest nigger in de worl’, caze I was a slave belonging to Marse Robert Toombs of Georgia; de grandest man dat ever lived, next to Jesus Christ.”

A more revealing, well-documented story is that of Garland H. White, an enslaved man who escaped Toombs’ ownership just before the Civil War and fled to Ontario. After the war erupted he heroically risked his freedom to join the United States Colored Troops. He served as an Army chaplain and traveled to recruit African-American soldiers. We found no mention at the Toombs memorial of White’s experience. In fact, we know of no monument to White in all of Georgia.

An average of $18,000 in county monies each year since 2011, plus $80,000 in state renovation funds in 2017 alone, have been devoted to this memorial to Toombs, who refused to take the oath of allegiance to the United States after the war and fled to Cuba and France to avoid arrest. Upon his return to Georgia, Toombs labored to circumscribe the freedom of African-Americans. “Give us a convention,” Toombs said in 1876, “and I will fix it so that the people shall rule and the Negro shall never be heard from.” The following year he got that convention, which passed a poll tax and other measures to disenfranchise black men.

* * *

It’s difficult to imagine that all the Confederate monuments and historic sites dotting the landscape today would have been established if African-Americans had had a say in the matter.

Historically, the installation of Confederate monuments went hand in hand with the disenfranchisement of black people. The historical record suggests that monument-building peaked during three pivotal periods: from the late 1880s into the 1890s, as Reconstruction was being crushed; from the 1900s through the 1920s, with the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, the increase in lynching and the codification of Jim Crow; and in the 1950s and 1960s, around the centennial of the war but also in reaction to advances in civil rights. An observation by the Yale historian David Blight, describing a “Jim Crow reunion” at Gettysburg, captures the spirit of Confederate monument-building, when “white supremacy might be said to have been the silent, invisible, master of ceremonies.”

Yet courageous black leaders did speak out, right from the start. In 1870, Douglass wrote, “Monuments to the ‘lost cause’ will prove monuments of folly ... in the memories of a wicked rebellion which they must necessarily perpetuate...It is a needless record of stupidity and wrong.”

In 1931, W.E.B. Du Bois criticized even simple statues erected to honor Confederate leaders. “The plain truth of the matter,” Du Bois wrote, “would be an inscription something like this: ‘sacred to the memory of those who fought to Perpetuate Human Slavery.’”

In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. joined a voting rights rally in Grenada, Mississippi, at the Jefferson Davis monument, where, earlier that day, an organizer named Robert Green declared, “We want brother Jefferson Davis to know the Mississippi he represented, the South he represented, will never stand again.”

In today’s debates about the public display of Confederate symbols, the strong objections of early African-American critics are seldom remembered, perhaps because they had no impact on (white) officeholders at the time. But the urgent black protests of the past now have the ring of prophecy.

John Mitchell Jr., an African-American, was a journalist and a member of Richmond’s city council during Reconstruction. Like his friend and colleague Ida B. Wells, Mitchell was born into slavery, and spent much of his career documenting lynchings and campaigning against them; also like Wells, he was personally threatened with lynching.

Arguing fiercely against spending public money to memorialize the Confederacy, Mitchell took aim at the movement to erect a grand Robert E. Lee statue, and tried to block funding for the proposed statue’s dedication ceremony. But a white conservative majority steamrolled Mitchell and the two other black council members, and the Lee statue was unveiled on May 29, 1890. Gov. Fitzhugh Lee, a nephew of Lee and a former Confederate general himself, was president of the Lee Monument Association, which executed the project. Virginia issued bonds to support its construction. The city of Richmond funded Dedication Day events, attended by some 150,000 people.

Mitchell covered the celebration for the Richmond Planet, the paper he edited. “This glorification of States Rights Doctrine—the right of secession, and the honoring of men who represented that cause,” he wrote, “fosters in the Republic, the spirit of Rebellion and will ultimately result in the handing down to generations unborn a legacy of treason and blood.”

In the past decade, Virginia has spent $174,000 to maintain the Lee statue, which has become a lightning rod for the larger controversy. In 2017, Richmond police spent some $500,000 to guard the monument and keep the peace during a neo-Confederate protest there.

* * *

In 1902, several years after nearly every African-American elected official was driven from office in Virginia, and as blacks were being systematically purged from voter rolls, the state’s all-white legislature established an annual allocation for the care of Confederate graves. Over time, we found, that spending has totaled roughly $9 million in today’s dollars.

Treating the graves of Confederate soldiers with dignity might not seem like a controversial endeavor. But the state has refused to extend the same dignity to the African-American men and women whom the Confederacy fought to keep enslaved. Black lawmakers have long pointed out this blatant inequity. In 2017, the legislature finally passed the Historical African American Cemeteries and Graves Act, which is meant to address the injustice. Still, less than $1,000 has been spent so far, and while a century of investment has kept Confederate cemeteries in rather pristine condition, many grave sites of the formerly enslaved and their descendants are overgrown and in ruins.

Significantly, Virginia disburses public funding for Confederate graves directly to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which distributes it to, among others, local chapters of the UDC and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Since 2009, Virginia taxpayers have sent more than $800,000 to the UDC.

The UDC, a women’s Confederate heritage group with thousands of members in 18 states and the District of Columbia, is arguably the leading advocate for Confederate memorials, and it has a history of racist propagandizing. One of the organization’s most influential figures was Mildred Lewis Rutherford, of Athens, Georgia, a well-known speaker and writer at the turn of the 20th century and the UDC’s historian general from 1911 to 1916.

Rutherford was so devoted to restoring the racial hierarchies of the past that she traveled the country in full plantation regalia spreading the “true history,” she called it, which cast slave owners and Klansmen as heroes. She pressured public schools and libraries across the South to accept materials that advanced Lost Cause mythology, including pro-Klan literature that referred to black people as “ignorant and brutal.” At the center of her crusade was the belief that slaves had been “the happiest set of people on the face of the globe,” “well-fed, well-clothed, and well-housed.” She excoriated the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency charged with protecting the rights of African-Americans, and argued that emancipation had unleashed such violence by African-Americans that “the Ku Klux Klan was necessary to protect the white woman.”

UDC officials did not respond to our interview requests. Previously, though, the organization has disavowed any links to hate groups, and in 2017 the president-general, Patricia Bryson, released a statement saying the UDC “totally denounces any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy.”

Confederate cemeteries in Virginia that receive taxpayer funds handled by the UDC are nonetheless used as gathering places for groups with extreme views. One afternoon last May, we attended the Confederate Memorial Day ceremony in the Confederate section of the vast Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond. We were greeted by members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Virginia Flaggers, a group that says its mission is to “stand AGAINST those who would desecrate our Confederate Monuments and memorials, and FOR our Confederate Veterans.”

An honor guard of re-enactors presented an array of Confederate standards. Participants stood at attention for an invocation read by a chaplain in period dress. They put their hands on their hearts, in salute to the Confederate flag. Susan Hathaway, a member of the Virginia Flaggers, led the crowd of several dozen in a song that was once the official paean to the Commonwealth:

Carry me back to old Virginny,

There’s where the cotton and the corn and taters grow,

There’s where the birds warble sweet in the springtime,

There’s where this old darkey’s heart am long’d to go.

* * *

“Very little has been done to address the legacy of slavery and its meaning in contemporary life.”

That scathing assessment of the nation’s unwillingness to face the truth was issued recently by the Equal Justice Initiative, the Montgomery-based legal advocacy group that in April 2018 opened the first national memorial to victims of lynching.

A few Confederate historical sites, though, are showing signs of change. In Richmond, the American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy have joined forces to become the American Civil War Museum, now led by an African-American CEO, Christy Coleman. The new entity, she said, seeks to tell the story of the Civil War from multiple perspectives—the Union and the Confederacy, free and enslaved African-Americans—and to take on the distortions and omissions of Confederate ideology.

“For a very, very long time” the Lost Cause has dominated public histories of the Civil War, Coleman told us in an interview. “Once it was framed, it became the course for everything. It was the accepted narrative.” In a stark comparison, she noted that statues of Hitler and Goebbels aren’t scattered throughout Germany, and that while Nazi concentration camps have been made into museums, “they don’t pretend that they were less horrible than they actually were. And yet we do that to America’s concentration camps. We call them plantations, and we talk about how grand everything was, and we talk about the pretty dresses that women wore, and we talk about the wealth, and we refer to the enslaved population as servants as if this is some benign institution.”

Stratford Hall, the Virginia plantation where Robert E. Lee was born, also has new leadership. Kelley Deetz, a historian and archaeologist who co-edited a paper titled “Historic Black Lives Matter: Archaeology as Activism in the 21st Century,” was hired in June as the site’s first director of programming and education. Stratford Hall, where 31 people were enslaved as of 1860, is revising how it presents slavery. The recent shocking violence in Charlottesville, Deetz said, was speeding up “the slow pace of dealing with these kinds of sensitive subjects.” She said, “I guarantee you that in a year or less, you go on a tour here and you’re going to hear about enslavement.”

In 1999, Congress took the extraordinary step of advising the National Park Service to re-evaluate its Civil War sites and do a better job of explaining “the unique role that slavery played in the cause of the conflict.” But vestiges of the Lost Cause still haunt park property. In rural Northern Virginia, in the middle of a vast lawn, stands a small white clapboard house with a long white chimney—the Stonewall Jackson Shrine, part of the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park. The Confederate general died in the house in May 1863. “The tendency for the park historically has been to invite people to mourn Jackson’s death,” John Hennessy, the park’s chief historian, told us. He believes that the site should be more than a shrine, however. Visitors, Hennessey said, should learn that Jackson “led an army in a rebellion in the service of a nation that intended to keep people in bondage forever.” He went on, “The greatest enemy to good public history is omission. We are experiencing as a society now the collateral damage that forgetting can inflict.”

A park ranger sitting in the gift shop rose to offer us a practiced talk that focused reverently on Jackson’s final days—the bed he slept on, the clock that still keeps time. The ranger said a “servant,” Jim Lewis, had stayed with Jackson in the small house as he lay dying. A plaque noted the room where Jackson’s white staff slept. But there was no sign in the room across the hall where Lewis stayed. Hennessy had recently removed it because it failed to acknowledge that Lewis was enslaved. Hennessy is working on a replacement. Slavery, for the moment, was present only in the silences.

* * *

During the Fall Muster at Beauvoir, the Jefferson Davis home, we met Stephanie Brazzle, a 39-year-old African-American Mississippian who had accompanied her daughter, a fourth grader, on a field trip. It was Brazzle’s first visit. “I always thought it was a place that wasn’t for us,” she said. Brazzle had considered keeping her daughter home, but decided against it. “I really do try to keep an open mind. I wanted to be able to talk to her about it.”

Brazzle walked the Beauvoir grounds all morning. She stood behind her daughter’s school group as they listened to re-enactors describe life in the Confederacy. She waited for some mention of the enslaved, or of African-Americans after emancipation. “It was like we were not even there,” she said, as if slavery “never happened.”

“I was shocked at what they were saying, and what wasn’t there,” she said. It’s not that Brazzle, who teaches psychology, can’t handle historic sites related to slavery. She can, and she wants her daughter, now 10, to face that history, too. She has taken her daughter to former plantations where the experience of enslaved people is a part of the interpretation. “She has to know what these places are,” Brazzle said. “My grandmother, whose grandparents were slaves, she told stories. We black people acknowledge that this is our history. We acknowledge that this still affects us.”

The overarching question is whether American taxpayers should support Lost Cause mythology. For now, that invented history, told by Confederates and retold by sympathizers for generations, is etched into the experience at sites like Beauvoir. In the well-kept Confederate cemetery behind the library, beyond a winding brook, beneath the flagpole, a large gray headstone faces the road. It is engraved with lines that the English poet Philip Stanhope Worsley dedicated to Robert E. Lee:

“No nation rose so white and fair, none fell so pure of crime.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/a1/31a1f370-9dd5-41b2-b84f-7894c7da5253/dec2018_g04_confederacy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/b5/16b54256-1a8c-4f95-b6ca-ef7ab99506df/dec2018_g13_confederacy.jpg)