This Crackerjack Lineup of Baseball Memorabilia Drives Home the Game’s American Essence

A new Library of Congress exhibition includes such treasures as the original 1857 “Magna Carta of Baseball”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/06/a006b4d2-7458-45aa-a17f-188538a6acfb/leadpic.jpg)

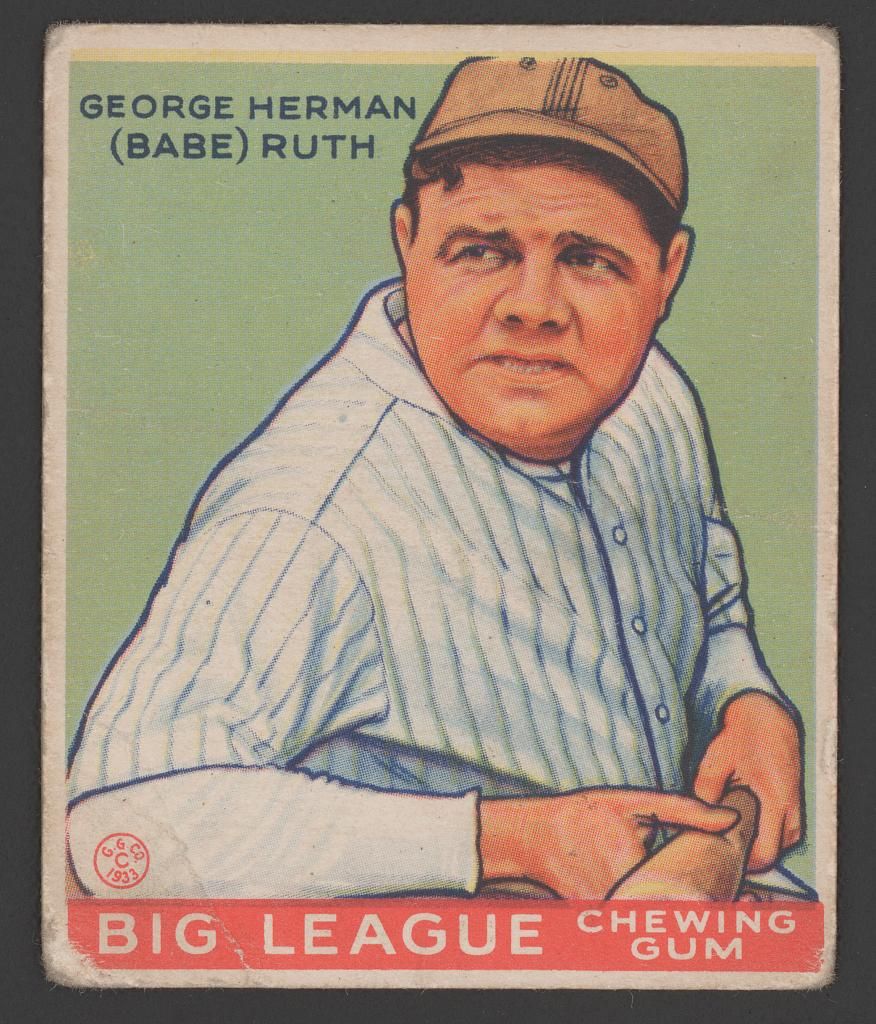

Baseball’s fidelity to its past easily outdistances that of any other sport. Not only are today’s players still compared to Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson, stars of the early 20th century, but baseball’s structure and rules are largely the same as they were more than a century ago.

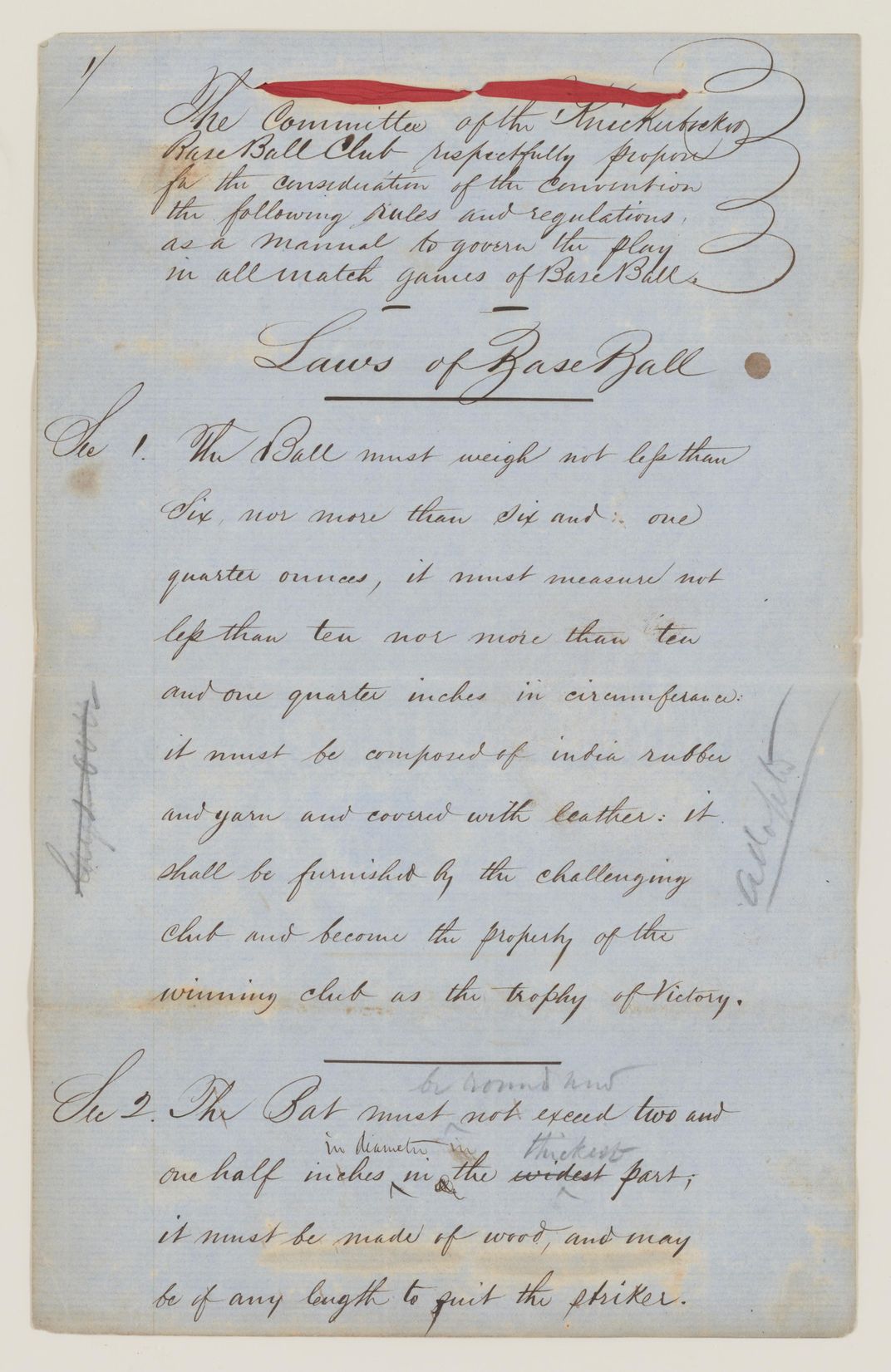

That connection is made especially vivid through the rediscovered 1857 “Laws of Base Ball,” a 14-page document, dubbed the sport’s Magna Carta, and making its first appearance in a major exhibition, at the Library of Congress. The revered artifact is on loan from Hayden Trubitt, a lifelong fan of the sport, who bought it at auction in April 2016 for $3.26 million, after taking out a $1 million mortgage on his home to do so.

Baseball historians were aware that an 1857 convention of New York-area clubs, initiated by the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, had standardized the rules of play. What they did not know for more than a century was that the document with its proposed and finalized rules had survived.

It made its debut without fanfare in a 1999 Sotheby’s auction. The winning bidder unwittingly purchased the document as part of a large collection of maps. Authentication came 16 years later, leading up to the Trubitt sale when John Thorn, the official historian of Major League Baseball, labeled it the “Magna Carta of baseball.”

“The provenance is impeccable,” Thorn says, “and it stands to reason that the Laws, as printed in the newspapers of the day had to have been based on a set of handwritten proposals from the Knickerbocker delegation, which called the convention into being.”

The document lays out the core of baseball—that the bases would be 90 feet apart; that a game would have nine innings; and that there would be nine players to a side. Former player Daniel ‘Doc’ Adams, elected as the presiding officer of the convention, authored the laws, which are exhibited along with two earlier drafts—the 1856 proposed Laws of Base Ball and the 1856-57 Rules for Match Games of Base Ball, which together formed the basis for the 1857 Laws). Other rules would be put in their modern form decades later—the pitching distance was set at its current distance in 1893—but it was with this document that baseball became the first organized sport in the United States. “These documents form a treasured part of Americana because baseball is our national game, to this very day,” says Thorn.

Observing that the manuscript includes notes of the deliberations written into the margins in real time, or “history as it is being made,” Trubitt, who has no collecting background or aspirations, speaks passionately about his find. “It would be hard to define the United States culturally without sports,” he says. “And that’s entirely on the basis of organized sports. The way baseball became organized in 1857 was through an amazingly American and democratic method. It was a convention of, by and for the players, with all views being taken into account in the amendments and voting. It wasn’t like anybody commanded this all to happen, as in college football. It is really remarkable and touching. It is an American story.”

David Mandel, chief of the interpretive programs office at the Library of Congress, says that the exhibition team chose to focus on the idea of baseball as community rather than emphasizing the sport’s chronology.

“It’s a thematic narrative,” says Mandel. “It’s about the origins of the game and also the expanding inclusivity in terms of who’s playing, about the culture of the ballpark and commercial aspects of the sport, and also a bit about the art and science of the game.”

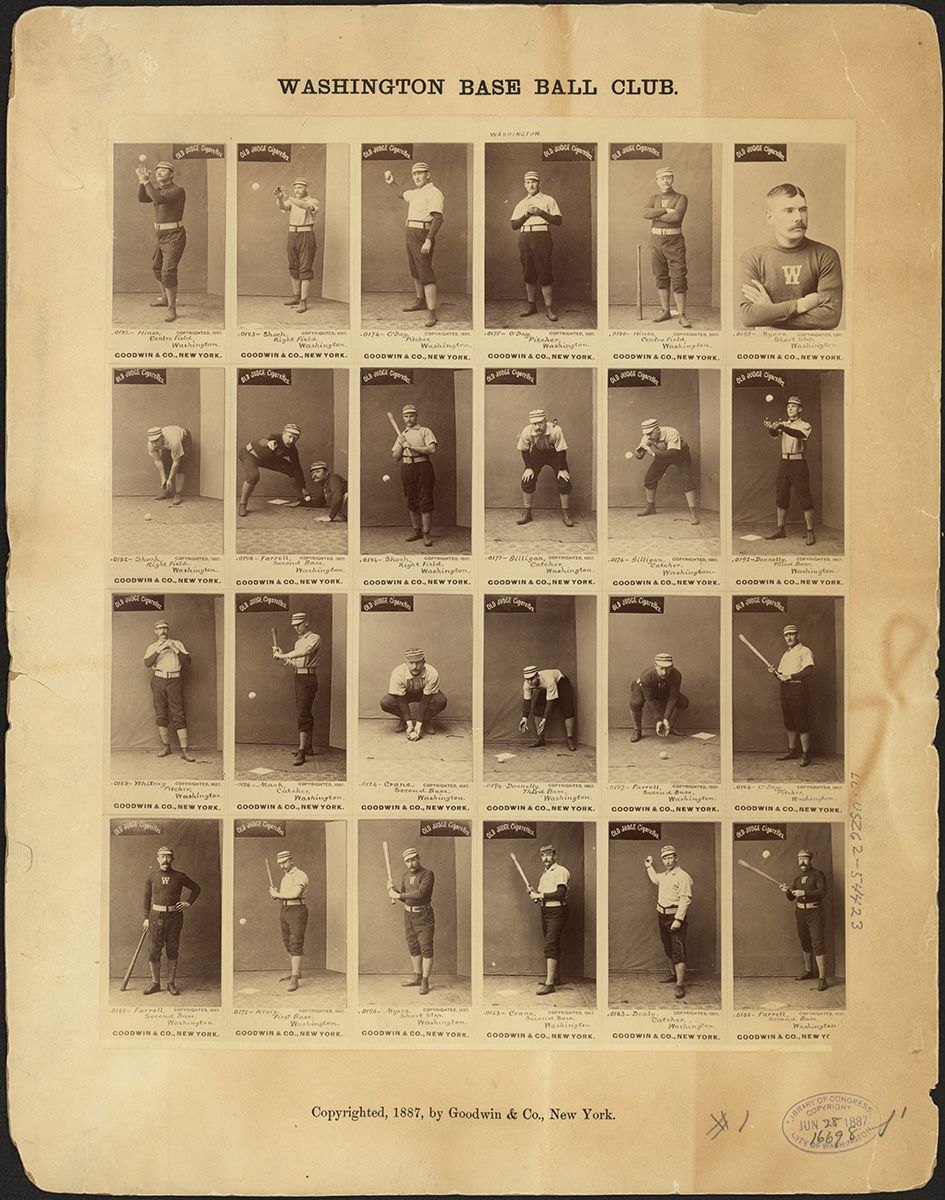

In the section titled "Who’s Playing," an uncut sheet of baseball cards of members of the Washington Base Ball Club from 1887 complements an uncut sheet of baseball cards from 1994.

“You see that some of the poses are comparable,” says Susan Reyburn, curator of the exhibit. “Players have moved from a studio in 1887, where they were posing for photos while standing on a floor with floral carpeting, a paper second base, and a ball hanging from a string to where you see pictures which were taken on the field. On the 1994 cards, you can see the incredible diversity—this is no longer the all-white Washington Base Ball Club. You’re seeing every manner of baseball player included in this other set.”

A heartfelt 1950 handwritten letter to Branch Rickey from Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to play in the major leagues, thanks the executive who gave Robinson the opportunity and changed the game forever. “It has been the finest experience I have had being associated with you and I want to thank you very much for all you have meant not only to me and my family but to the entire country and particularly the members of our race,” wrote Robinson.

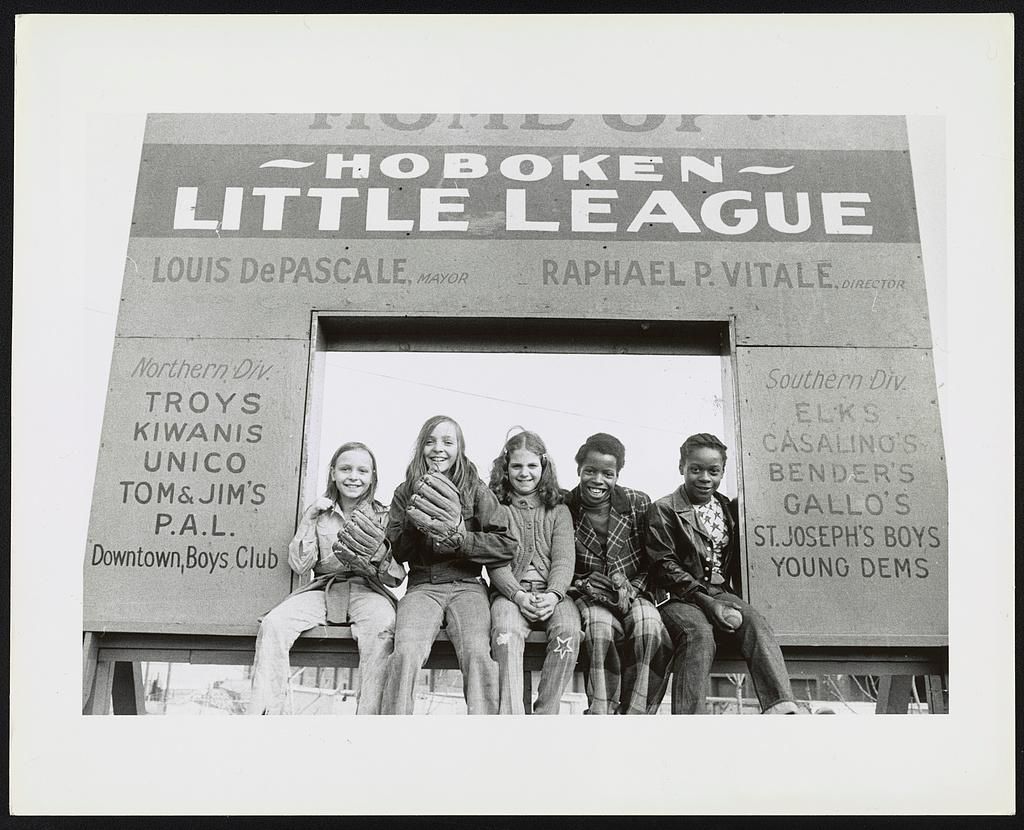

A Rockford Peaches uniform belonging to pre-eminent base stealer Dottie Ferguson Key, who played in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League from 1945 through 1954 is a highlight. The incredibly short skirt shows what little protection she had for her dirt sliding skids—she stole 461 bases in 950 games. A 1974 print by photographer Bettye Lane, titled Little League Tryouts for Females, New Jersey is also a remarkable tribute to the young girls who finally became eligible to play in 1974.

Among the various pieces of equipment on loan from the Baseball Hall of Fame are Babe Ruth’s shoes, which look more like something a coal miner would wear than any kind of athletic footwear. But what is just as striking is Babe Ruth’s auxiliary agreement from 1921, laying out how he could earn various monetary performance incentives all while his ability to change teams was restricted by baseball’s reserve clause. The same principle which legally bound players to their respective teams was embodied in an 1892 Western League contract, also on display.

“This is what baseball players spend the next century fighting against,” says Reyburn. “One of the themes that runs through baseball is the players trying to fight for their liberty, here in the freest county in the world. And it’s right here in this very innocuous-looking document. The reserve clause is going to cause strikes and many battles between players and owners through the 1970s. There it is, in very wordy language, which basically says, ‘we own you.’”

A 27’ high grandstand, which attendees can go around and through, was created by a design company to provide a physical manifestation of what it is like to come together in the stands. “The way we would define a community for the purposes of this exhibit, in the United States, when the weather is nice, on any given day, people are playing baseball or softball,” says Mandel. “From Omaha to Oakland, from Albany to Atlanta. Baseball is a part of the fabric of American life that way, with the quotidian nature of it.”

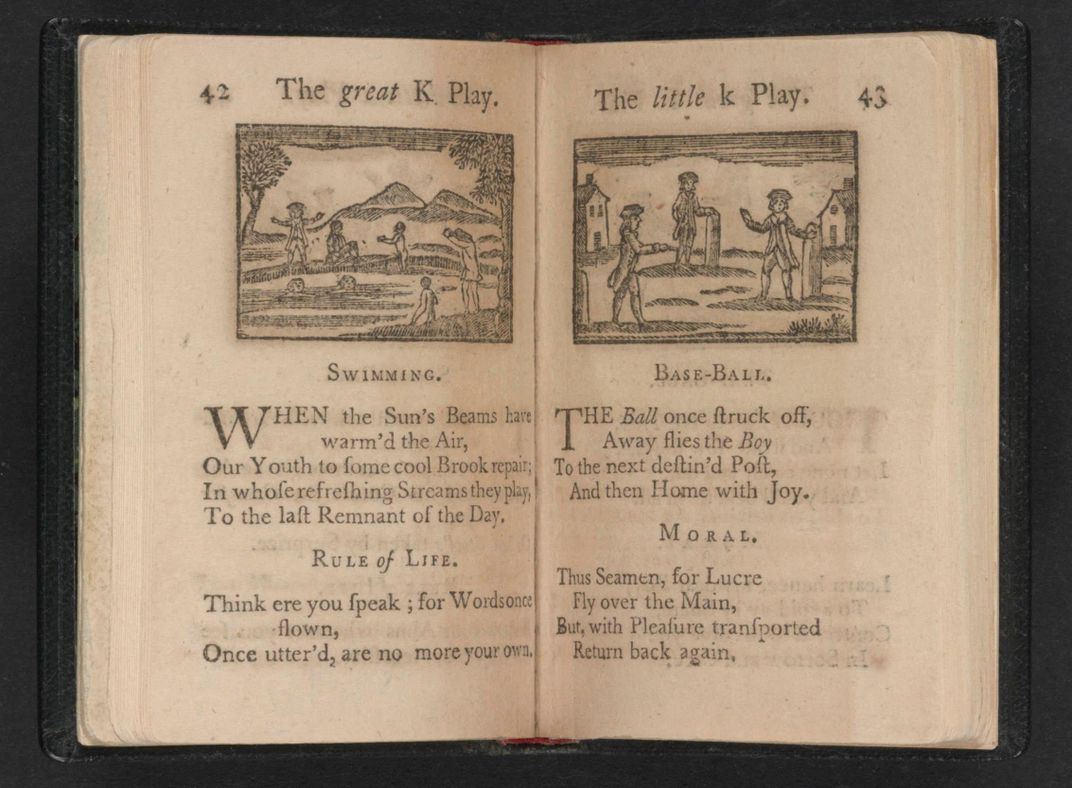

Even while going back to baseball’s roots, the Library of Congress exhibition connects to the present. A children’s book from 1787 titled A Little Pretty Pocket Book, first printed in England in 1744, shows figures standing by posts, which function as bases, and includes the first mention of the sport in print along with a now famous verse: “Base-Ball/The Ball once struck off/Away flies the Boy/To the next destin’d Post/and then Home with Joy.” The pairing in the exhibit with H Is For Home Run, a 2009 children’s book, underscores that baseball books for children have been produced for more than two centuries.

“Unlike other organized sports, baseball has been with us from the beginning of the United States, as an activity,” says Reyburn. “I think there is a feeling that even though football is something of the national game, baseball is the national pastime. Even now. More people are playing baseball and softball than any other sport. Baseball is sort of in our DNA, because from the 1780s, whether we realize it or not, the term ‘baseball’ has been here, and bat and ball games have been here. With the additions to baseball that Americans have made over the generations, I think there’s this feeling of ownership. We made this folk game our own.”

“Baseball Americana” is on view at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. through June 2019.

John N. McMurray will visit the Smithsonian October 1, 2018 for an evening program with Smithsonian Associates to examine how the World Series came to be, along with a fascinating replay of highlights from Series history. Purchase tickets here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JMcMurray_photo.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JMcMurray_photo.jpeg)