Created 150 Years Ago, the Justice Department’s First Mission Was to Protect Black Rights

In the wake of the Civil War, the government’s new force sought to enshrine equality under the law

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fa/a9/faa90e6a-6010-4382-a92b-df743ccc6de6/nast-cartoon-kkk.jpg)

Amos T. Akerman was an unlikely figure to head the newly formed Department of Justice. In 1870, the United States was still working to bind up the nation’s wounds torn open by the Civil War. During this period of Reconstruction, the federal government committed itself to guaranteeing full citizenship rights to all Americans, regardless of race. At the forefront of that effort was Akerman, a former Democrat and enslaver from Georgia, and a former officer in the Confederate Army.

Though the United States had had an Attorney General since the formation of the government in 1789, none had been empowered with the full force of a consolidated legal team quite like Akerman. And none had had the monumental task of enforcing the 14th and 15th Amendments and new legislation delivering long overdue rights to four million formerly enslaved black men and women. This department’s work on behalf of the emancipated population was so central to its early mission that Akerman established the department’s headquarters in the Freedman’s Savings Bank Building.

In the immediate wake of the Civil War, Akerman, a New Hampshirite who had settled in Georgia in the 1840s, looked to the future, leaving the Democrats for the Republicans and prosecuting voter intimidation cases as a U.S. district attorney in his adopted state. Reflecting on his decision to switch his allegiance to the party of Lincoln, Akerman said, “Some of us who had adhered to the Confederacy felt it to be our duty when we were to participate in the politics of the Union, to let Confederate ideas rule us no longer….Regarding the subjugation of one race by the other as an appurtenance of slavery, we were content that it should go to the grave in which slavery had been buried.”

Akerman’s work caught the attention of President Ulysses S. Grant, who promoted the Georgian to Attorney General in June 1870. On July 1 of that year, the Department of Justice, created to handle the onslaught of post-war litigation, became an official government department with Akerman at its helm. The focus of his 18-month tenure as the nation’s top law enforcement official was the protection of black voting rights from the systematic violence of the Ku Klux Klan. Akerman’s Justice Department prosecuted and chased from Southern states hundreds of Klan members. Historian William McFeely, in his biography of Akerman, wrote, “Perhaps no attorney general since his tenure…has been more vigorous in the prosecution of cases designed to protect the lives and rights of black Americans.”

McFeely is perhaps best known for his 1981 Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography, Grant, which he says he wrote in order to help him make sense of the modern civil rights movement. "To understand the 1960s, I studied the 1860s," McFeely said in a 2018 interview. In Akerman, McFeely saw the promise of what could have been, had his work in the Justice Department been allowed to flourish.

Foremost, Akerman was a lawyer, who, according to McFeely, “welcomed the firm, unequivocal law he found in the Reconstruction amendments.” Meanwhile, the Klan offended Akerman’s principles; to Akerman, McFeely wrote, “disguised night riders taking the law in their own hands meant no law at all.” The government had a short window within which to act, he thought, before the nation would forget the consequences of disunion and inequality. “Unless the people become used to the exercise of these powers now, while the national spirit is still warm with the glow of the late war,…the ‘state rights’ spirit may grow troublesome again.”

Indeed, white Democrats in South Carolina, the state that fired upon Fort Sumter to start the Civil War, would lead the postwar campaign to maintain their white supremacist empire. The Klan, founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1865, had entrenched itself in upcountry South Carolina counties by 1868. Blacks, newly emancipated, now comprised a majority of voters in the state and most voted Republican, the party led by Grant, that was safeguarding their lives and rights.

Lou Falkner Williams, in her book, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871-1872 wrote that the Klan conducted a year-long reign of terror throughout the region starting with the November 1870 elections, whipping black and white Republican voters. An army general sent down to quell the riots, after local police and state troops failed to do so, estimated the Klan numbered more than 2,000 sworn members in York County alone. “The South Carolina Klan in its fury,” Williams wrote, “committed some the most heinous crimes in the history of the United States.” The 1910 novel The Clansman, on which the film The Birth of a Nation is based, reportedly draws on these events in York County.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/f1/12f1e8d8-1c6e-4e45-9500-062dc6bae87a/gettyimages-3112166.jpg)

In reaction to the racial violence, Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which Grant signed into law on April 20, 1871, providing Akerman unprecedented tools to subdue the Klan. The KKK Act authorized the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, which allowed the Justice Department to detain suspected Klan members, keep them in custody, and not immediately bring them to trial. The department could also withhold disclosure of the identities of suspects and the evidence against them, which allowed Akerman to make mass arrests and gather evidence without the parties conspiring with each other. Using these tools, Akerman obtained hundreds of convictions in South Carolina and throughout the South. Author Ron Chernow, in his own Grant, reports that on one day in November 1871, 250 people in one South Carolina county confessed their affiliation with the Klan.

One would think that Akerman’s record of success would have pleased Grant, but the President relieved Akerman of his duties in December of 1871. The common explanation for the dismissal is that Akerman, who Chernow describes as “honest and incorruptible,” scrutinized the land deals struck between railroad barons and the government. McFeely put the blame on the nation’s attachment to white supremacy. “Men from the North as well as the South came to recognize, uneasily, that if he was not halted, his concept of equality before the law was likely to lead to total equality,” he wrote.

Employed at the time as Akerman’s clerk in the Justice Department, the poet Walt Whitman shared the anxieties of his countrymen, giving voice to this sentiment in his “Memoranda During the War.” He equates black citizenship rights in the former “Slave States” as “black domination, but little above the beasts” and hopes it not remain a permanent condition. He posits if slavery had presented problems for the nation, “how if the mass of the blacks in freedom in the U.S. all through the ensuing century, should present a yet more terrible and more deeply complicated problem?” Whitman scholar Kenneth M. Price writes in his forthcoming book, Whitman in Washington: Becoming the National Poet in the Federal City, “Like much of the late nineteenth-century American culture, [Whitman] grew fatigued with the case of African Americans during Reconstruction and beyond.”

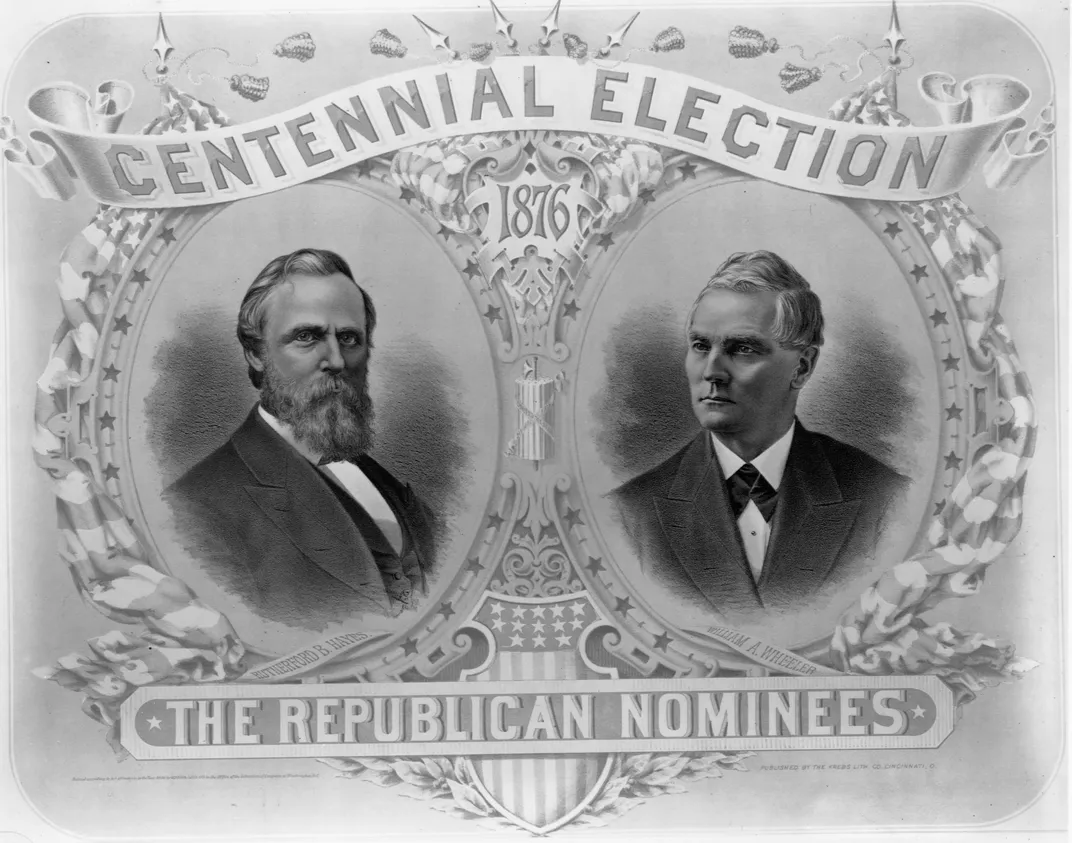

Reconstruction fell apart following the contested election of Rutherford B. Hayes. Democrats conceded the election to the Republican Hayes in exchange for the withdrawal of all federal troops from the former Confederacy. Yet, the five years between Akerman’s departure from the Department of Justice and the 1876 compromise would be the most violent of the Reconstruction period. While Akerman and his immediate successor, George Henry Williams, had crushed the Klan, paramilitary organizations like the White League continued to terrorize the black citizenry throughout the South. In 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, America witnessed what historian Eric Foner called “the bloodiest single act of carnage in all of Reconstruction,” when an all-black militia in the Republican county seat tried to defend the courthouse from a white paramilitary attack.

If Akerman was the most consequential Attorney General for black civil rights in the Department of Justice’s 150 years, Herbert Brownell, who served from 1953-1958 under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, contends for second place. It was on Brownell’s advice that, in 1957, for the first time since Reconstruction, federalized national guard troops enforced the civil rights of black Americans. In this case, it was to enforce the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Brownell was also instrumental in the appointment of five desegregationist Supreme Court justices, most notably Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the United States. Warren’s court would hand down the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education decision, overturning the 1896 decision Plessy v. Ferguson that provided the legal justification for six decades of Jim Crow. This court would sustain the Brown jurisprudence in later cases. Finally, Brownell was the principal architect of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first federal civil rights legislation since 1875. While the final legislation was not as strong as the “Brownell Bill,” as it was known while pending, the Act did create the Department of Justice’s venerated Civil Rights Division. Yet, Brownell, like Akerman nearly a century before him, stepped down because, as historian Stephen Ambrose put it, he was “more insistent on integration than Eisenhower wanted him to be.”

After witnessing nearly a century of inaction from the Department of Justice, black Americans began to look cautiously to the agency to defend their rights during the 1950s and ’60s. The department proceeded haltingly, often reluctantly. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the investigative arm of the department, created in 1908, became a chief antagonist of the organized civil rights movement. When Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference formed in 1957 on the heels of the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, the FBI began to monitor, investigate and harass the group as a possible subversive organization with Communist ties.

The department proved itself a better friend to civil rights activists during Robert Kennedy’s tenure as Attorney General. With John Doar leading the department’s Civil Rights Division, the government helped protect the Freedom Riders, forced the integration the University of Mississippi and prosecuted the murderers of civil rights workers. But Kennedy came to civil rights slowly and grudgingly. While he pressed segregationist governors to do right by their black citizens, he and his brother, John F. Kennedy, were careful not to scare unreconstructed Southern Democrats from the party.

Kennedy also authorized FBI surveillance of King. During the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies, civil rights workers risking their lives in the Jim Crow South saw J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI as unwilling to intervene while blacks were brutalized, and at worse, engaged in an active effort to undermine civil rights leaders. Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of slain civil rights leader Medgar Evers said, “We saw the FBI only as an institution to keep people down... One that was not a friend, but one that was a foe.”

The suspicion of the FBI in the black community only grew during the Nixon administration, and justifiably so. Nixon’s counsel John Ehrlichman confessed in a 1994 interview, “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people.” The FBI’s COINTELPRO operation, which began over a decade earlier, increasingly surveilled black leaders. Now, the government labeled advocates for civil rights the nation’s troublemakers, defining “law and order” as protecting white America from the violent activists.

About Nixon’s rhetoric, Marquette University professor Julia Azari told the Washington Post that “law and order” is “often a way to talk about race without talking about race. But its 1960s meaning also meant all people who were challenging the social order. As we’ve moved away from the era when politicians were making obvious racial appeals, the appeals have become more coded. The question becomes whose order, for whom does the law work.”

In a June 2020 interview, civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson said that “blacks emancipated from slavery believed that their rights, their dignity, their humanity was now going to be embraced, that they were going to be welcomed as full citizens of the United States.”

The Reconstruction amendments failed, he said, because, “We’re still committed to this doctrine of white supremacy.” Stevenson, who founded the Equal Justice Initiative, holds that the nation cannot overcome racial violence until it learns this history and recognizes it as an integral part of American history to the present day.

Langston Hughes, in his poem, “I, Too,” responds to Walt Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing,” which celebrates the diversity of America, yet makes no explicit mention of African Americans. Hughes reminds Whitman, in a poem that graces the history galleries of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, “I am the darker brother/They send me to eat in the kitchen.” He reminds us all, “I, too, sing America.”

Or, in today’s parlance, Black Lives Matter, too.