How Cuba Remembers Its Revolutionary Past and Present

On the 60th anniversary of Fidel Castro’s secret landing on Cuba’s southern shore, our man in Havana journeys into the island’s rebel heart

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/0c/4b0c70d1-c8a8-4bec-b95d-b84b996e756d/oct2016_f02_cuba.jpg)

It’s not hard to see why Fidel Castro’s guerrilla headquarters during the Cuban revolutionary war was never found by the army. Even today, getting to the command post feels like a covert mission. Known as Comandancia La Plata, the remote hide-out was built in the spring of 1958 in the succulent rainforest of the Sierra Maestra at Cuba’s eastern tip, and it still lies at the end of steep, treacherous, unpaved roads. There are no road signs in the Sierra, so photographer João Pina and I had to stop our vehicle and ask for directions from passing campesinos on horseback while zigzagging between enormous potholes and wandering livestock. In the hamlet of Santo Domingo, we filled out paperwork in quadruplicate to secure access permits, before an official government guide ushered us into a creaky state-owned four-wheel-drive vehicle. This proceeded to wheeze its way up into one of the Caribbean’s last wilderness areas, with breathtaking views of rugged green peaks at every turn.

The guide, Omar Pérez, then directed us toward a steep hiking trail, which ascends for a mile into the forest. Rains had turned stretches into muddy streams, and the near-100 percent humidity had us soaked with sweat after only a few steps. A spry local farmer, Pérez pushed us along with mock-military exhortations of Vámanos, muchachos! By the time I spotted the first shack—the dirt-floored field hospital set up by the young medical graduate Ernesto “Che” Guevara—I looked like a half-wild guerrilla myself.

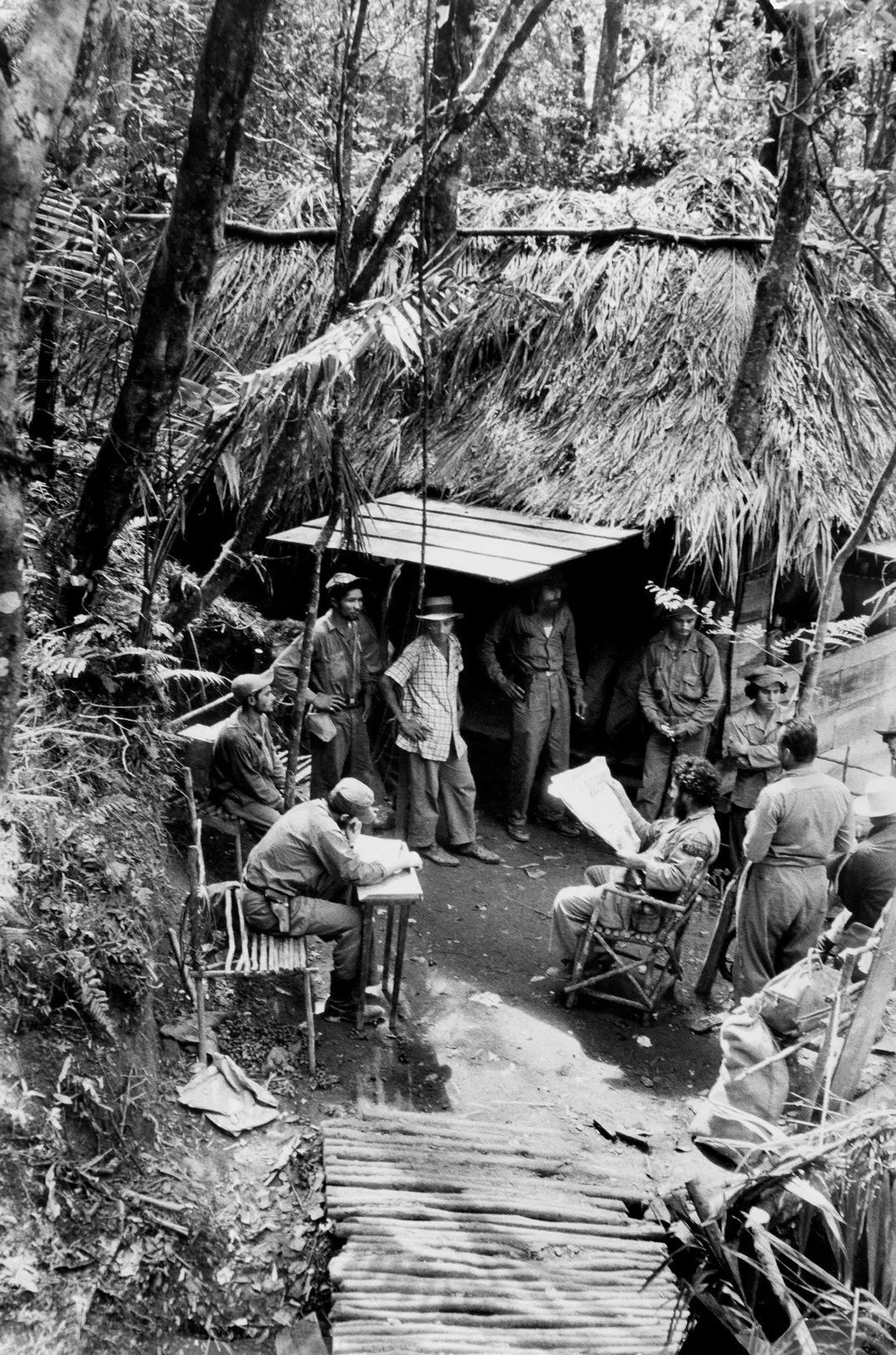

In any other country, the Comandancia would make an excellent eco-lodge, but in Cuba it remains one of the revolution’s most intimate historical shrines. The base was first carved out in April 1958 and continued to be Fidel’s main command post until December 1958, as the guerrillas gained one unexpected victory after the next and began to seize the rest of the island. Its 16 thatch-roofed huts were home to some 200 rebel soldiers and had the ambience of a self-contained—and strikingly beautiful—jungle republic.

The structures are all original, Pérez insisted, and are lovingly labeled with wooden signs. Che’s hospital was used to treat wounded guerrillas and enemy soldiers, and ill local peasant supporters. (“Che performed a lot of dentistry here,” Pérez said. “Not very well.”) Paths lead to the press office, where the rebels’ newspaper, El Cubano Libre, was produced mostly by hand. At the summit, Radio Rebelde was transmitted around Cuba using an antenna that could be raised and lowered unseen.

The main attraction is La Casa de Fidel—Castro’s cabin. Perched on a ledge above a burbling stream, with large windows propped open by poles to let in a cooling breeze, it’s a refuge that would suit a Cuban John Muir. The spacious two-room hut was designed by his resourceful secretary, rural organizer and lover, Celia Sánchez, and the interior still looks like the revolutionary power couple has just popped out for a cigar. There is a pleasant kitchen table and gasoline-fueled refrigerator used to store medicines, complete with bullet holes from when it was shot at while being transported on the back of a mule. The bedroom still has the couple’s armchairs, and an ample double bed with the original mattress now covered in plastic. Raised in a well-to-do family of landowners, Fidel enjoyed his creature comforts, but Celia also thought it important for visitors to see the rebel leader well established and comfortable—acting, in fact, as if the war were already won and he was president of Cuba. She would serve guests fine cognac, cigars and potent local coffee even as enemy airplanes strafed randomly overhead. Celia even managed to get a cake to the hut packed in dry ice via mule train for Fidel’s 32nd birthday.

The interior of the cabin is off-limits to visitors, but when Pérez meandered off, I climbed up the ladder and slipped inside. At one point, I lay down on the bed, gazing up at a window filled with jungle foliage and mariposa flowers like a lush Rousseau painting. It was the ideal place to channel 1958—a time when the revolution was still bathed in romance. “The Cuban Revolution was a dream revolution,” says Nancy Stout, author of One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution. “It didn’t take too long. It worked. And it was filled with these extraordinary, larger-than-life characters.” As it was unfolding, the outside world was fascinated by the spectacle of a ragtag bunch of self-taught guerrillas, many of them barely out of college, who managed to overthrow one of Latin America’s most brutal dictatorships. “It was,” says Stout, “like an operetta.”

But even the hallowed Comandancia cannot escape Cuba’s modern realities, as the Socialist system is slowly being dismantled. As we hiked back down the mountain, Pérez explained that he had landed his prized job as a guide a decade ago, in part because his grandfather had helped the rebels in the 1950s. Although he has a university degree in agricultural engineering, he said he makes far more money in tourism than he could on a state-run farm. “My salary is 14 CUC [$16] a month, but I get by on propinitas, little tips,” he added pointedly. Pérez also hoped the opening of the economy since 2011 by Raúl Castro—Fidel’s younger brother, a guerrilla who also spent time at the Comandancia—would speed up. “Cuba has to change!” he said. “There’s no other way for us to move forward.”

It was a startling admission at such a hallowed revolutionary spot. Ten years ago, he might have been fired for such a declaration.

**********

Cubans love anniversaries, and this December 2 marks one of its greatest milestones: the 60th anniversary of the secret landing of Granma, the ramshackle boat that brought Fidel, Che, Raúl and 79 other barely trained guerrillas to start the revolution in 1956. Che later described it as “less a landing than a shipwreck,” and only a quarter of the men made it to the Sierra Maestra—but it began the campaign that would, in a little over two years, bring down the Cuban government and reshape world politics. To me, the coming anniversary was an ideal excuse for a road trip to untangle a saga whose details I, like many who live in the United States, know only vaguely. Within Cuba, the revolutionary war is very much alive: Almost everywhere the guerrillas went now has a lavish memorial or a quasi-religious museum featuring artifacts like Che’s beret, Fidel’s tommy gun, or homemade Molotov cocktails. It’s still possible to meet with people who lived through the battles, and even the younger generation likes to remain on a first-name basis with the heroes. Cubans remain extremely proud of the revolution’s self-sacrifice and against-all-odds victories. Recalling that moment of hope can be as startling as seeing photographs of the young Fidel without a beard.

**********

“The war was both a long time ago and not so long ago,” says Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. “For Americans, the best way to understand what the era was like is to visit Cuba itself. You see the world as it was 60 years ago, without expressways or fast-food stores or strip malls. Today, the U.S. has been tamed. It’s a suburban landscape. But in the 1950s, there were no cellphones, no internet, there weren’t even many telephones. Everything moved in a different time frame.”

Following the path of the revolutionary war also leads to corners of Cuba that few travelers reach. While most outsiders are fascinated by Havana, with its rococo mansions and retro-chic hotels funded by the American mob, the cradle of revolt was at the opposite end of the long, slender island, in the wild, thinly populated Oriente (“East”).

Cuba was the last Spanish possession in the Americas, and two vicious 19th-century wars of independence began there. Victory in the second was plucked from Cuban hands by the intervention of the United States in the Spanish-American War in 1898. The humiliating Platt Amendment, passed by Congress in 1901, made it legal for the U.S. to intervene in Cuban politics, a safeguard that protected a flood of Yanqui investment. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt repealed the law in 1934, the island remained a virtual American colony, with everything from power plants to sugar plantations in U.S. hands. This troubled situation took a dire turn in 1952, when a strongman with matinée idol looks named Fulgencio Batista seized power in a coup. Although Cuba remained one of the wealthiest nations in Latin America, Batista’s rule was marked by blatant corruption and a savage level of political repression.

“If you really want to understand the Cuban Revolution, you should start in Santiago cemetery,” Nancy Stout advised me before I flew to the city. Santiago de Cuba, whose palm-fringed plazas and colonial cathedrals now bask in splendid decay, is the country’s second-largest city. No sooner had I arrived than I hopped on the back of a motorbike taxi and gritting my teeth in the unnerving traffic, sped to the ancient necropolis of Santa Ifigenia. The memorial to “Those Fallen in the Insurgency” is a simple wall with dozens of bronze plaques, each one adorned with a fresh red rose, naming those killed by Batista’s security forces, usually after sickening torture. Many mutilated bodies were found strung from trees in city parks or dumped in gutters. Some victims were as young as 14 and 15. “The police officer in charge of Santiago was, literally, a psychopath,” Stout said. “Some of Batista’s generals had only fifth-grade educations. The ‘leftist agitators’ they were executing were often just kids.” On one occasion, the mothers of Santiago staged a protest march carrying placards that said: Stop the Murder of Our Sons. “A lot of everyday Cubans—students, bricklayers, teachers—were simply fed up.”

One of those was the young law graduate Fidel Castro Ruiz. Born into a wealthy landowning family some 60 miles north of Santiago, Fidel was from his teens known for a rebellious nature, hypnotic charisma and staggering self-confidence. At university in Havana he became involved in radical student politics and at age 24 planned to run as a progressive candidate in the 1952 election, before Batista canceled it. Photographs of him from the time show a tall, well-fed youth, often in a snappy suit, V-neck sweater and tie, and sporting a pencil mustache. With his chances of working within the system gone, Fidel and fellow activists in 1953 decided to take direct action.

The story would seem straight out of Woody Allen’s Bananas if the consequences had not been so tragic. With about 160 inexperienced men (and two women) disguised as soldiers, Fidel planned to storm government sites including a Santiago barracks called La Moncada, where he would surprise the 1,000 or so troops—who were hopefully sleeping off hangovers due to the previous evening’s carnival celebrations— and escape with a cache of arms. This resounding victory, Fidel hoped, would provoke Cubans to rise up against Batista and restore constitutional democracy. From the start, it was a fiasco. As his convoy of 15 cars approached the Moncada before dawn on July 26, it ran into two patrolmen. Fidel stopped his car and leapt out to deal with them, but this confused the other rebels, who mistook a military hospital for the Moncada and began firing wildly. By the time they had regrouped, soldiers were everywhere. Fidel ordered a retreat, but most of his men surrendered.

The reaction of the army shocked Cubans. Five of the attackers had been killed in the shootout, but 56 prisoners were summarily executed and their bodies scattered in the Moncada’s hallways to make it look as if they had been killed in battle. Many, in fact, had been gruesomely tortured. The eyes of one leader, Abel Santamaría, were gouged out and presented to his sister in an attempt to make her reveal their hide-out. Fidel was captured in the countryside soon after, by a by-the-books officer who refused to hand his prisoner over to superiors who wanted to dispense summary justice. It was the first of countless lucky breaks in the story of the revolution. Although Fidel and his men were sentenced to 15 years in prison, the “26th of July Movement” was born.

Fidel spent two years incarcerated on the Isle of Pines, Cuba’s answer to Devil’s Island, reading Marx and becoming ever more radical. Nothing short of true revolution would change Cuba, he concluded, although the chances of his becoming personally involved seemed remote. Then, in 1955, Batista succumbed to popular opinion and included Fidel and his compañeros in an amnesty of political prisoners. It was a moment of over-confidence that the dictator would soon regret.

From exile in Mexico City, Fidel concocted a plan that seemed even more harebrained than the Moncada attack: to return to Cuba in a secret amphibious landing and begin an insurgency in the mountains. He bought a secondhand boat, the Granma, from an American expat and gathered a band of fellow firebrands, among them Ernesto Guevara. A quiet Argentine, quickly nicknamed “Che” (an Argentine term of affection), Guevara had haunting good looks and a steely willpower born of years battling asthma. It was an attraction of opposites with the strapping, extroverted Fidel that would turn into one of history’s great revolutionary partnerships.

**********

Travel in Cuba is never straightforward. Airport lines can take three hours, hotels demand mysterious printed “vouchers” and the few eccentric rental car companies are booked three months in advance. The Granma landing site and Sierra base are unusually far-flung, so an enterprising Cuban friend of a friend offered to drive us there in his own car for a tidy sum in U.S. dollars. But just before flying to Santiago, I received a forlorn message: “Bad news, compañeros, very bad news...” The driver had been given a parking fine in Havana and lost his license. It was time to scramble for Plan B. We soon had a dozen local insiders scouring Cuba for any possible vehicle, with emails flying to expat acquaintances as far away as Toronto and Brussels. At the 11th hour, I received a message from a certain Esther Heinekamp of Cuba Travel Network, an educational agency based in Europe. She had tracked down a rental car in Santiago—“the last rental in the entire country!” I’d like to say it was a 1955 Chevrolet, but it turned out to be a silver MG, circa 2013. Still, on a steamy afternoon I drove us south of Santiago toward the famous Granma landing site, along one of the most spectacular and worst-maintained roads in the Western Hemisphere. On this wild shore, the ocean hits the coast with terrifying force. Much of the route has been wrecked by hurricanes and landslides, becoming a bare expanse of slippery rocks that could only be traversed at five miles an hour.

The Granma landing site, still pristine, is part of a national park, and the lone guide on duty, a jovial woman named Yadi León, seemed astonished to see us. We were the only visitors that day, she admitted, directing us toward a sun-blasted concrete walkway that had been laid across the mangroves. As dozens of tiny black crabs scuttled underfoot, León recounted the legendary story that every Cuban schoolchild knows by heart. The Granma had turned out to be barely seaworthy, more suited for a pleasure cruise than a military operation, and was seriously overloaded. “Fidel had calculated the journey from Mexico to Cuba would take five days,” León marveled. “But with over 80 men crowded onboard, it took seven.” As soon as they hit open ocean, half the passengers became seasick. Local supporters who had planned to meet the boat when it landed gave up when it failed to appear on time. As government air patrols threatened them on December 2, Fidel ordered the pilot to head to shore before sunrise, unaware that he had chosen the most inhospitable spot on the entire Cuban coastline.

At around 5:40 a.m., the Granma hit a sandbank, and the 82 men groggily lurched into the hostile swamp. The guerrillas were basically city slickers, and few had even seen mangroves. They sunk waist-deep into mud and struggled over abrasive roots. When they finally staggered onto dry land, Fidel burst into a farmer’s hut and grandly declared: “Have no fear, I am Fidel Castro and we have come to liberate the Cuban people!” The baffled family gave the exhausted and half-starved men pork and fried bananas. But the army had already gotten wind of their arrival, and three days later, on December 5, the rebels were caught in a surprise attack as they rested by a sugar-cane field. The official figure is that, of the 82 guerrillas, 21 were killed (2 in combat, 19 executed), 21 were taken prisoner and 19 gave up the fight. The 21 survivors were lost in the Sierra. Soldiers were swarming. As Che laconically recalled: “The situation was not good.”

Today, our stroll through the mangroves was decidedly less arduous, although the 1,300-meter path gives a vivid idea of the claustrophobia of the alien landscape. It was a relief when the horizon opened up to the sparkling Caribbean. A concrete jetty was being installed on the landing spot for the upcoming 60th anniversary celebrations, when a replica of the Granma will arrive for the faithful to admire. The gala on December 2 will be a more extravagant version of the fiesta that has been held there every year since the 1970s, León explained, complete with cultural activities, anthems and “acts of political solidarity.” The highlight is when 82 young men jump out of a boat and re-enact the rebels’ arrival. “But we don’t force them to wade through the swamp,” she added.

**********

A few days after the Granma debacle, the handful of survivors were reunited in the mountains with the aid of campesinos. One of the most beloved anecdotes of the war recounts the moment Fidel met up with his brother Raúl. Fidel asked how many guns he had saved. “Five,” Raúl answered. Fidel said he had two, then declared: “Now we’ve won the war!” He wasn’t joking. His fantastical confidence was unbowed.

As they settled into the Sierra Maestra, the urban intellectuals quickly realized they were now dependent on the campesinos for their very survival. Luckily, there was a built-in reservoir of support. Many in the Sierra had been evicted from their land by the Rural Guards and were virtual refugees, squatting in dirt-floor huts and subsisting by growing coffee and marijuana. Their generations of despair had already been tapped by Celia Sánchez, a fearless young activist for the 26th of July Movement who was at the top of Batista’s most-wanted list in the Oriente. A brilliant organizer, Sánchez would soon become Fidel’s closest confidante and effective second in command. (The romance with Fidel developed slowly over the following months, says biographer Stout. “Fidel was so tall and handsome, and he had a really sweet personality.”)

Young farmhands swelled the rebel ranks as soldiers. Girls carried rebel missives folded into tiny squares and hidden (as Celia mischievously explained) “in a place where nobody can find it.” Undercover teams of mules were organized to carry supplies across the Sierra. A farmer even saved Che’s life by hiking into town for asthma medication. The campesinos also risked the savage reprisals of soldiers of the Rural Guard, who beat, raped or executed peasants they suspected of rebel sympathies.

Today, the Sierra is still a frayed cobweb of dirt roads that lead to a few official attractions—oddities like the Museum of the Heroic Campesino—but my accidental meetings are more vivid. On one occasion, after easing the car across a surging stream, I approached a lonely hut to ask for directions, and the owner, a 78-year-old gentleman named Uvaldo Peña Mas, invited me in for a cup of coffee. The interior of his shack was wallpapered with ancient photographs of family members, and he pointed to a sepia image of a poker-faced, middle-aged man—his father, he said, who had been murdered early in Batista’s rule. The father had been an organizer for the sharecroppers in the area, and one day an assassin walked up and shot him in the face. “I still remember when they brought in his body,” he said. “It was 8 in the morning. People came from all around, friends, relatives, supporters. Of course, we had to kill a pig to feed them all at the funeral.” Although he supported the revolution, he recalled that not everyone who joined Fidel was a hero. “My next-door neighbor joined the guerrillas,” Peña said wryly. “He was a womanizer, a drunk, a gambler. He ran away to join the guerrillas to get out of his debts.”

**********

For six months, Fidel and his battered band lay low, training for combat and scoring unusual propaganda points. The first came when Batista told the press that Fidel had been killed after the landing, a claim the rebels were quickly able to disprove. (To this day, Cubans relish photos of the 1956 newspaper headline FIDEL CASTRO DEAD.) The next PR coup came in February 1957, when New York Times correspondent Herbert Matthews climbed into the Sierra for the first interview with Fidel. Matthews was star-struck, describing Fidel with enthusiasm as “quite a man—a powerful six-footer, olive-skinned, full-faced.” Castro had stage-managed the meeting carefully. To give the impression that his tiny “army” was larger than it was, he ordered soldiers to walk back and forth through the camp in different uniforms, and a breathless messenger to arrive with a missive from the “second front”—a complete fiction. The story was splashed across the front page of the Times, and a glowing TV interview with CBS followed, shot on Cuba’s highest summit, Mount Turquino, with postcard-perfect views. If he had not become a revolutionary, Fidel could have had a stellar career in advertising.

A more concrete milestone came on May 28, 1957, when the guerrillas, now numbering 80 men, attacked a military outpost in the drowsy coastal village of El Uvero. The bloody firefight was led by Che, who was showing an unexpected talent as a tactician and a reckless indifference to his own personal safety; his disciplined inner circle would soon be nicknamed “the Suicide Squad.” Today, a monument with a gilded rifle marks Fidel’s lookout above the battle site, although visitors are distracted by the coastal views that unfold like a tropical Big Sur. Elderly residents still like to recount the story of the attack in detail. “It was 5:15 in the afternoon when we heard the first gunshots,” Roberto Sánchez, who was 17 at the time, told me proudly in a break from picking mangoes. “We all thought it was the Rural Guards training. We had no idea! Then we realized it was Fidel. From that day on, we did what we could to help him.”

“This was the victory that marked our coming of age,” Che later wrote of El Uvero. “From this battle on, our morale grew tremendously.” The emboldened guerrillas began to enjoy success after success, descending on the weak points of the vastly more numerous Batista forces, then melting into the Sierra. Their strategies were often improvised. Fidel later said he fell back for ideas on Ernest Hemingway’s novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which describes behind-the-lines combat in detail.

By mid-1958, the rebels had established Comandancia La Plata and a network of other refuges, and even the self-deluded Batista could not deny that the government was losing control of the Oriente. In summer, the dictator ordered 10,000 troops into the Sierra backed with air support, but after three tortuous months, the army withdrew in frustration. When the rebels revealed how many civilians were being killed and mutilated by napalm bombing, the U.S. government stopped Cuban air force flights from refueling at the Guantánamo naval base. Congress ended U.S. arms supplies. The CIA even began feeling out contacts with Fidel.

Sensing victory, Fidel in November dispatched Che and another comandante, Camilo Cienfuegos, to seize the strategic city of Santa Clara, located in the geographical center of Cuba. The 250-mile dash was one of the most harrowing episodes of the campaign, as troops slogged through flat sugar country exposed to strafing aircraft. But by late December, Che had surrounded Santa Clara and cut the island in two. Although 3,500 well-armed government troops were defending the city against Che’s 350, the army surrendered. It was a stunning victory. The news reached Batista back in Havana early on New Year’s Eve, and the panicked president concluded that Cuba was lost. Soon after the champagne corks popped, he was escaping with his cronies on a private plane loaded with gold bullion to the Dominican Republic. He soon moved to Portugal, then under a military dictatorship, and died from a heart attack in Spain in 1973.

Despite its revolutionary credentials, Santa Clara today is one of the most decrepit provincial outposts in Cuba. The Art Deco hotel in the plaza is pockmarked with bullet holes, relics of when army snipers held out on the tenth floor, and sitting by a busy road in the middle of town are a half-dozen carriages from the Tren Blindado, an armored train loaded with weapons that Che’s men derailed on December 29. A strikingly ugly memorial has been erected by the carriages, with concrete obelisks placed at angles to evoke an explosion. Guards show off burn marks from rebel bombs on the train floors, before cheerfully trying to sell visitors black market Cohiba cigars.

As the site of his greatest victory, Santa Clara will always be associated with Che. His remains are even buried here in the country’s most grandiose memorial, complete with a statue of the hero marching toward the future like Lenin at Finland Station. Still, the story of Che’s last days is a discouraging one for budding radicals. In the mid-1960s, he tried to apply his guerrilla tactics to other impoverished corners of the world with little success. In 1967, he was captured by the Bolivian Army in the Andes and executed. After the mass grave was rediscovered in 1997, Che’s remains were interred with much fanfare in Santa Clara by an eternal flame. The mausoleum is now guarded by cadres of young military women dressed in olive-drab miniskirts and aviator sunglasses, who loll about in the heat like Che groupies. An attached museum offers some poignant exhibits from Che’s childhood in Argentina, including his leather asthma inhaler and copies of schoolbooks “read by young Ernesto.” They include Tom Sawyer, Treasure Island and—perhaps most appropriately—Don Quixote.

**********

It was around 4:30 a.m. on New Year’s Day, 1959, when news filtered though Havana of Batista’s flight. What happened next is familiar—in broad brushstrokes—to anyone who has seen The Godfather Part II. To many Cubans, the capital had become a symbol of decadence, a seedy enclave of prostitution, gambling and raunchy burlesque shows for drunken foreign tourists. Lured by the louche glamour, Marlon Brando, Errol Flynn and Frank Sinatra took raucous holidays in Havana, actor George Raft became master of ceremonies at the mob-owned Capri Hotel, and Hemingway moved to a leafy mansion on the city outskirts so he could fish for marlin in the Caribbean and guzzle daiquiris in the bar El Floridita.

Batista’s departure let loose years of frustration. By dawn, crowds were taking out their anger on symbols of Batista’s rule, smashing parking meters with baseball bats and sacking several of the American casinos. Fidel ordered Che and Camilo to rush ahead to Havana to restore order and occupy the two main military barracks. The spectacle of 20,000 soldiers submitting to a few hundred rebels was “enough to make you burst out laughing,” one guerrilla, Carlos Franqui, later wrote, while the grimy Camilo met the U.S. ambassador with his boots off and feet on a table, “looking like Christ on a spree.”

Fidel traveled the length of Cuba in a weeklong “caravan of victory.” The 1,000 or so guerrillas in his column, nicknamed Los Barbudos, “the bearded ones,” were greeted as heroes at every stop. The cavalcade finally arrived in Havana on January 8, with Fidel riding a tank and chomping a cigar. “It was like the liberation of Paris,” Anderson says. “No matter your political persuasion, nobody loved the police or the army. People had been terrorized. And here were these baseball-playing, roguish, sexy guys who roll into town and chase them off. By all accounts, it was an orgy.” Fidel rode his tank to the doors of the brand-new Havana Hilton and took the presidential suite for himself and Celia. Other guerrillas camped out in the lobby, treading mud over the carpets, while tourists going to the pool looked on in confusion.

As for us, we too were soon triumphantly speeding along the Malecón, Havana’s spectacular seafront avenue, which looks just as it did when Graham Greene’s novel Our Man in Havana came out the month before Fidel’s victory. (“Waves broke over the Avenida de Maceo and misted the windscreens of cars,” Greene wrote. “The pink, green, yellow pillars of what had once been the aristocrat’s quarter were eroded like rocks; an ancient coat of arms, smudged and featureless, was set over the doorway of a shabby hotel, and the shutters of a night club were varnished in bright crude colors to protect them from the wet and salt of the sea.”) Compared with in the countryside, the old revolutionary spirit has only a tenuous hold in Havana. Today, the city has come full circle to the wild 1950s, with bars and restaurants sprouting alongside nightclubs worked by jineteras, freelance prostitutes.

The baroque Presidential Palace now houses the Museum of the Revolution, but it is a shabby affair, its exhibits fraying in cracked, dusty cases. A glimpse of the feisty past is provided by the notorious Corner of the Cretins, a propaganda classic with life-size caricatures of Batista and U.S. presidents Reagan, Bush senior and junior. A new exhibit for Castro’s 90th birthday celebration was unironically titled “Gracias por Todo, Fidel!” (“Thanks for Everything, Fidel!”) and included the crib in which he was born.

Shaking the country dust from my bag, I emulated Fidel and checked into the old Hilton, long ago renamed the Habana Libre (Free Havana). It was perversely satisfying to find that the hotel has defied renovation. It’s now as frayed and gray as Fidel’s beard, towering like a tombstone slab above the seaside suburb of Vedado. The marble-floored lobby is filled with leftover modernist furniture beneath Picasso-esque murals, and the cafe where Fidel came for a chocolate milkshake every night is still serving. My room on the 19th floor had million-dollar views of Havana, although the bath taps were falling off the wall and the air conditioner gave a death rattle every time I turned it on.

I made a formal request to visit the Presidential Suite, which had been sealed up like a time capsule since Fidel decamped after several months. It was a voyage into the demise of the Cuban dream. A portly concierge named Raúl casually hit me up for a propinita as he accompanied me to the 23rd floor, and seconds after we stepped out of the elevator, a blackout hit. While we used the light from my iPhone to find our way, we could hear the increasingly shrill cries of a woman stuck in the elevator a couple of floors down.

When we cracked the double doors, Fidel’s suite exploded with sunlight. With its Eisenhower-era furniture and vintage ashtrays, it looked like the perfect holiday apartment for Don Draper. Celia’s room had floor-to-ceiling copper-toned mirrors, one of which was still cracked after Fidel kicked it in a tantrum. But the suite’s period stylishness couldn’t distract from the creeping decay. A crumbling sculpture in the main hallway was threatened by a pool of brownish water accumulating on the floor; part of the railing on the wraparound veranda was missing. As we left, we heard the woman trapped in the elevator still screaming: “Por dios, ayúdame! Help!” I left Raúl yelling to her, “Cálmase, Señora! Calm yourself, madam!” I left, nervously, in another lift.

**********

The years 1959 and 1960 were the “honeymoon phase” of the revolution. Indeed, most of the world was fascinated by the romantic victory of a handful of idealistic guerrillas forcing an evil dictator to flee.

Fidel and Che basked in celebrity, entertaining intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir and a stream of third-world leaders. At first, the affection also extended to the United States. When Fidel arrived on a goodwill tour in 1959, he was thronged by admirers: He was the keynote speaker at the American Society of Newspaper Editors in Washington, D.C., ate a hot dog in New York City and visited Mount Vernon. Soon American college kids were flocking to Cuba to see the brave new world firsthand.

Never had a revolution been so photogenic. The photographer Roberto Solas, a Cuban-American kid from the Bronx, was 18 when he saw the “victory caravan” roll into Havana. “The Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution, their icons were statues and paintings. In Cuba, the revolution was established with photographs.” The camera loved the enigmatic Che in particular, whose every image seemed to have a mythic aura. (Away from the cameras’ eyes, executions of the most sinister of Batista’s torturers, informers and henchmen were conducted by Che in the Spanish fortress of La Cabaña, sometimes with disturbing show trials by the so-called Cleansing Commission.)

Revolutionary tourism immediately took off. In January 1960, Che’s parents and siblings arrived from Buenos Aires to tour Santa Clara. Dozens of others beat their way on to the Comandancia La Plata in the Sierra Maestra to bask in its aura. In February, Che and Fidel personally escorted the visiting deputy premier of the Soviet Union, Anastas Mikoyan, to the aerie on a sightseeing trip, and the group spent the night chatting by a campfire. Secret negotiations with the Cuban Communist Party were already being conducted. Now Che and Fidel openly declared their intention of pursuing a socialist revolution, and asked for Soviet economic aid.

“At heart, Fidel was a left-of-center nationalist who wanted to break away from U.S. domination,” said Jon Lee Anderson. “You have to remember that Americans owned everything in Cuba—planes, ferries, electricity companies. How do you gain political sovereignty? You have to kick them out. Fidel knew a confrontation was coming, and he needed a new sponsor.” The overture was well received by envoys caught up in the Cuban romance. “The Russians were euphoric,” Anderson said. “They thought these young guys were like the Bolsheviks, the men their grandfathers knew.”

The argument over whether Cuba was pushed or jumped to become part of the Eastern bloc may never be fully settled. But by early 1961, the tit for-tat standoff with the U.S. was in full swing, and escalated rapidly after Fidel began nationalizing American companies. When the CIA-backed Bay of Pigs invasion came just after midnight on April 17, 1961, the Cuban population was already armed with Soviet weapons.

“Of course, none of these leftists had actually been to Russia,” Anderson said. “Travel was so much more difficult then. And when Che did visit Moscow, he was shocked—all these guys wearing old woolen suits from the 1940s and eating onions they carried in their pockets. This was not the New Socialist man he had imagined.” If only Fidel and Che had been more diligent tourists, history might have taken another course.

Related Reads

One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)