Curses! Archduke Franz Ferdinand and His Astounding Death Car

Was the man whose assassination began World War I riding in a car destined to bring death to a series of owners?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Past-Imperfect-Ferdinand-631.jpg)

It’s hard to think of another event in the troubled 20th century that had quite the shattering impact of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. The archduke was heir to the throne of the tottering Austro-Hungarian empire; his killers—a motley band of amateurish students—were Serbian nationalists (or possibly Yugoslav nationalists; historians remain divided on the topic) who wanted to turn Austrian-controlled Bosnia into a part of a new Slav state. The guns and bombs they used to kill the archduke, meanwhile, were supplied by the infamous “Colonel Apis,” head of Serbian military intelligence. All of this was quite enough to provoke Austria-Hungary into declaring war on Serbia, after which, with the awful inevitability that A.J.P. Taylor famously described as “war by timetable,” Europe slid inexorably into the horrors of the First World War as the rival Great Powers began to mobilize against one another.

To say that all this is well-known is an understatement—I have dealt with one of the stranger aspects of the story before in Past Imperfect. Seen from the historian’s perspective, though, even the most familiar of the events of that day have interesting aspects that often go unremarked. The appalling combination of implausible circumstance that resulted in assassination is one; Franz Ferdinand had survived an earlier attempt to kill him on the fateful day, emerging unscathed from the explosion of a bomb that bounced off the folded roof of his convertible and exploded under a car following behind him in his motorcade. That bomb injured several members of the imperial entourage, and those men were taken to the hospital. It was Franz Ferdinand’s impulsive decision, later in the day, to visit them there—a decision none of his assassins could have predicted—that took him directly past the spot where his assassin, Gavrilo Princip, was standing. It was chauffeur Leopold Lojka’s unfamiliarity with the new route that led him to take a wrong turn and, confused, pull to a halt just six feet from the gunman.

For the archduke to be presented, as a stationary target, to the one man in a crowd of thousands still determined to kill him was a remarkable stroke of bad luck, but even then, the odds still favored Franz Ferdinand’s survival. Princip was so hemmed in by the crowd that he was unable to pull out and prime the bomb he was carrying. Instead, he was forced to resort to his pistol, but failed to actually aim it. According to his own testimony, Princip confessed: “Where I aimed I do not know,” adding that he had raised his gun “against the automobile without aiming. I even turned my head as I shot.” Even allowing for the point-blank range, it is pretty striking, given these circumstances, that the killer fired just two bullets, and yet one struck Franz Ferdinand’s wife, Sophie—who was sitting alongside him—while the other hit the heir to the throne. It is astonishing that both rounds proved almost immediately fatal. Sophie was hit in the stomach, and her husband in the neck, the bullet severing his jugular vein. There was nothing any doctor could have done to save either of them.

There are stranger aspects to the events of June 28 than this, however. The assassination proved so momentous that it is not surprising that there were plenty of people ready to say, afterward, that they had seen it coming. One of them, according to an imperial aide, was the fortuneteller who had apparently told the archduke that “he would one day let loose a world war.” That story carries a tang of after-the-fact for me. (Who, before August 1914, spoke in terms of a “world war”? A European war, perhaps). Yet it seems pretty well established that Franz Ferdinand himself had premonitions of an early end. In the account of one relative, he had told told some friends the month before his death that “I know I shall soon be murdered.” A third source has the doomed man “extremely depressed and full of forebodings” a few days before the assassination took place.

According to yet another story, moreover, Franz Ferdinand had every reason to suppose that he was bound to die. This legend—not found in the history books but (says the London Times) preserved as an oral tradition among Austria’s huntsmen—records that, in 1913, the heavily armed archduke had shot a rare white stag, and adds that it was widely believed of any hunter who killed such an animal “that he or a member of his family shall die within a year.”

There is nothing inherently implausible in this legend—or at least not in the idea that Franz Ferdinand might have mown down a rare animal without thinking twice about it. The archduke was a committed and indiscriminate huntsman, whose personal record, when in pursuit of small game (Roberta Feueurlicht tells us), was 2,140 kills in a day and who, according to the records he meticulously compiled in his own game book, had been responsible for the deaths of a grand total of 272,439 animals during his lifetime, the majority of which had been loyally driven straight toward his overheating guns by a large assembly of beaters.

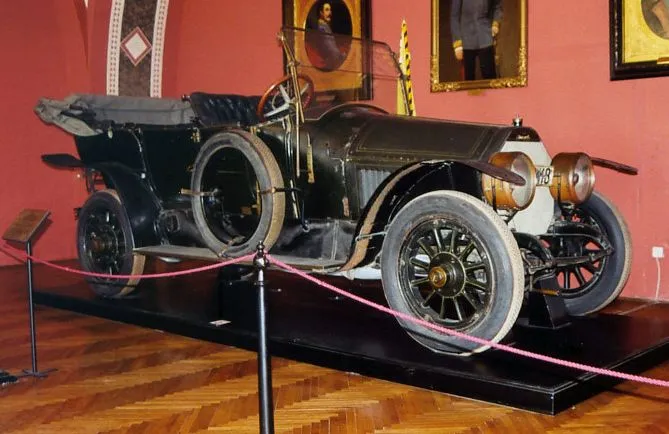

Of all the tall tales that attached themselves to Franz Ferdinand after his death, however, the best known and most widely circulated concerns the car in which he was driven to his death. This vehicle—a Gräf and Stift double phaeton, built by the Gräf brothers of Vienna, who had been bicycle manufacturers only a few years earlier—had been made in 1910 and was owned not by the Austro-Hungarian state but by Count Franz von Harrach, “an officer of the Austrian army transport corps” who apparently lent it to the archduke for his day in Sarajevo. According to this legend, Von Harrach’s vehicle was so cursed by either its involvement in the awful events of June 1914 or, perhaps, its gaudy blood-red paint job that pretty much every subsequent owner met a hideous, Final Destination sort of end.

It’s sensible to point out, first, that the story of the cursed death car did not begin to make the rounds until decades after Franz Ferdinand’s death. It dates, so far as I have been able to establish, only to 1959, when it was popularized in Frank Edwards’s Stranger Than Science. This is not a terribly encouraging discovery. Edwards, a hack writer who wrote a series of sensational books recounting paranormal staples across one or two pages of purple prose, rarely offered his readers anything so persuasive as an actual source; he was prone to exaggeration and untroubled by outright invention. To make matters worse, Edwards wrote up the story of the jinxed Gräf & Stift at pretty much the same time that a very similar tale concerning James Dean’s cursed Porsche Spyder had begun to make the rounds in the United States.

It would be unfair, however, to hold Edwards solely responsible for the popularity of the death car legend. In the decades since he wrote, the basic tale accumulated additional detail, as urban legends tend to do, so that by 1981 the Weekly World News was claiming that the blood-red Gräf & Stift was responsible for more than a dozen deaths.

Pared down to its elements, the News’ version of the story, which still makes the rounds online, tells the story in the words of a 1940s Vienna museum curator named Karl Brunner—and it opens with him refusing to allow visitors to “climb into the infamous ‘haunted car’ that was one of his prize exhibits.” The remainder of the account runs like this:

After the Armistice, the newly appointed Governor of Yugoslavia had the car restored to first-class condition.

But after four accidents and the loss of his right arm, he felt the vehicle should be destroyed. His friend Dr. Srikis disagreed. Scoffing at the notion that a car could be cursed, he drove it happily for six months–till the overturned vehicle was found on the highway with the doctor’s crushed body beneath it.

Another doctor became the next owner, but when his superstitious patients began to desert him, he hastily sold it to a Swiss race driver. In a road race in the Dolomites, the car threw him over a stone wall and he died of a broken neck.

A well-to-do farmer acquired the car, which stalled one day on the road to market. While another farmer was towing it for repairs, the vehicle suddenly growled into full power and knocked the tow-car aside in a careening rush down the highway. Both farmers were killed.

Tiber Hirschfield, the last private owner, decided that all the old car needed was a less sinister paint job. He had it repainted in a cheerful blue shade and invited five friends to accompany him to a wedding. Hirschfield and four of his guests died in a gruesome head-on collision.

By this time the government had had enough. They shipped the rebuilt car to the museum. But one afternoon Allied bombers reduced the museum to smoking rubble. Nothing was found of Karl Brunner and the haunted vehicle. Nothing, that is, but a pair of dismembered hands clutching a fragment of steering wheel.

It’s a nice story–and the wonderful suggestive detail in the last sentence, that Brunner had finally succumbed to the temptation to climb behind the wheel himself, and in doing so drew down a 1,000-pound bomb onto his head, is a neat touch. But it’s also certifiable rubbish.

To begin with, many of the details are plain wrong. Princip did not leap onto the running board of the Gräf & Stift, and—as we have seen—he certainly didn’t pump “bullet after bullet” into his victims. Nor did Yugoslavia have a “governor” after 1918; it became a kingdom. And while it is true that Franz Ferdinand’s touring car did make it to a Vienna museum—the military museum there, as a matter of fact—it wasn’t destroyed by bombing in the war. It’s still on display today, and remains one of the museum’s main attractions.

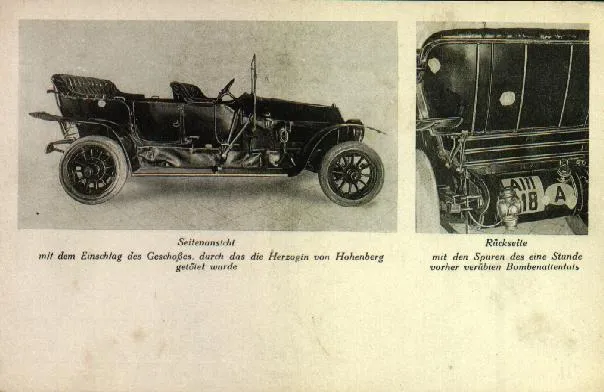

The car is not painted blood red, you’ll notice, nor “a cheerful blue shade,” and—rather more significantly—it displays no sign of any damage caused by a long series of ghastly road accidents and head-on collisions. It does still bear the scars of the bombs and the bullets of June 28, however, and that seems pretty odd for a vehicle that must (at the very least) have undergone top-to-tail reconstruction work on three occasions for the death car legend to be true. There’s no evidence whatsoever, in short, that the vehicle ever suffered through the bloody experiences attributed to it by Frank Edwards and those who copied him–and though I can find no indication that anyone has ever done a full-fledged reinvestigation of Edwards’ original tale, there’s no sign in any of the more reputable corners of my library, or online, of any “Tiber Hirschfield,” nor of a “Simon Mantharides,” a bloodily deceased diamond merchant who crops up in several variants accounts of the tale, nor of a dead Vienna museum curator named Karl Brunner. All of these names can be found solely in recountings of the legend itself.

In closing, though, I want to draw attention to an even more astounding coincidence concerning Franz Ferdinand’s death limo—one that is considerably better evidenced than the cursed-car nonsense. This tiny piece of history went completely unremarked on for the best part of a century, until a British visitor named Brian Presland called at Vienna’s Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, where the vehicle is now on display. It was Presland who seems to have first drawn the staff’s attention to the remarkable detail contained in the Gräf & Stift’s license plate, which reads AIII 118.

That number, Presland pointed out, is capable of a quite astonishing interpretation. It can be taken to read A (for Armistice) 11-11-18— which means that the death car has always carried with it a prediction not of the dreadful day of Sarajevo that in a real sense marked the beginning of the First World War, but of November 11, 1918: Armistice Day, the day that the war ended.

This coincidence is so incredible that I initially suspected that it might be a hoax—that perhaps the Gräf & Stift had been fitted with the plate retrospectively. A couple of things suggest that this is not the case, however. First, the pregnant meaning of the intitial ‘A’ applies only in English—the German for ‘armistice’ is Waffenstillstand, a satisfyingly Teutonic-sounding mouthful that literally translates as “arms standstill.” And Austria-Hungary did not surrender on the same day as its German allies—it had been knocked out of the war a week earlier, on November 4, 1918. So the number plate is a little bit less spooky in its native country, and so far as I can make it out it also contains not five number 1′s, but three capital ‘I’s and two numbers. Perhaps, then, it’s not quite so perplexing that the museum director buttonholed by Brian Presland said he had worked in the place for 20 years without spotting the plate’s significance.

More important, however, a contemporary photo of the fateful limousine, taken just as it turned into the road where Gavrilo Princip was waiting for it, some 30 seconds before Franz Ferdinand’s death, shows the car bearing what looks very much like the same number plate as it does today. You’re going to have to take my word for this—the plate is visible, just, in the best-quality copy of the image that I have access to, and I have been able to read it with a magnifying glass. But my attempts to scan this tiny detail in high definition have been unsuccessful. I’m satisfied, though, and while I don’t pretend that this is anything but a quite incredible coincidence, it certainly is incredible, one of the most jaw-dropping I’ve ever come across.

And it resonates. It makes you wonder what that bullet-headed old stag-murderer Franz Ferdinand might have made of it, had he had any imagination at all.

Sources

Roberta Feuerlicht. The Desperate Act: The Assassination at Sarajevo. New York: McGraw Hill, 1968; The Guardian , November 16, 2002; David James Smith. One Day in Sarajevo: 28 June 1914. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008; Southampton Echo November 12, 2004; The Times, November 2, 2006; Weekly World News, April 28, 1981.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)