The Cuyahoga River Caught Fire at Least a Dozen Times, but No One Cared Until 1969

Despite being much smaller than previous fires, the river blaze in Cleveland 50 years ago became a symbol for the nascent environmental movement

:focal(685x657:686x658)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/13/e4136a97-b510-432c-8089-15a4d7ba50f7/gettyimages-515303088.jpg)

It was the summer of 1969, and recent high school graduate Tim Donovan needed a job to pay his college tuition. When it came to well-paid summer work in Cleveland, there was one good place to look: the steel mills. Donovan went to work as a hatch tender for Jones & Laughlin Steel, standing at the top of machines stationed along the river to help unload ore carriers. It was his first real interaction with the Cuyahoga River, and the experience didn’t endear him to it.

“The river was a scary little thing,” Donovan says. “There was a general rule that if you fell in, God forbid, you would go immediately to the hospital.”

The water was nearly always covered in oil slicks, and it bubbled like a deadly stew. Sometimes rats floated by, their corpses so bloated they were practically the size of dogs. It was disturbing, but it was also just one of the realities of the city. For more than a century, the Cuyahoga River had been prime real estate for various manufacturing companies. Everyone knew it was polluted, but pollution meant industry was thriving, the economy was booming, and everyone had jobs.

To the surprise of no one who worked on the Cuyahoga, an oil slick on the river caught fire the morning of Sunday, June 22, 1969. The blaze only lasted about 30 minutes, extinguished by land-based battalions and one of the city’s fireboats. It caused about $50,000 in damage to railroad bridges spanning the river and earned a small amount of attention in the local press. The fire was so small and short-lived that no one managed to get a single photo of it. For Donovan, the summer ended uneventfully and he went off to school without having thought much further on the state of Lake Erie or the Cuyahoga River.

What happened next was the real surprise.

Time magazine published an article on the fire—with an accompanying photo from an incident in 1952. National Geographic featured the river in their December 1970 cover story “Our Ecological Crisis” (but managed to get the date of the fire wrong). Congress established the Environmental Protection Agency in January 1970, for the first time creating a federal bureau to oversee pollution regulations. In April 1970, Donovan was one of 1,000 students marching down to the river for the country’s first Earth Day. The nation, it seemed, had suddenly woken up to the realities of industrial pollution, and the Cuyahoga River was the symbol of calamity.

But on the day of the fire, it had meant nothing to the masses. Only in the following months and years did the fire gain its strange significance. As historians David and Richard Stradling write, “The fire took on mythic status, and errors of fact became unimportant to the story’s obvious meaning. … Clearly this transformative fire must have been massive; the nation must have seen the flames and been appropriately moved. Neither is true.”

**********

The Civil War turned Cleveland into a manufacturing city almost overnight. The Cuyahoga River, just south of the city’s downtown area, snaking for 100 miles across Ohio and emptying into Lake Erie, proved the perfect place for factories to set up camp. American Ship Building, Sherwin-Williams Paint Company, Republic Steel and Standard Oil all rose up from Cleveland, and the river bore the toxic legacy of their success. By the 1870s, the river had served as an open sewer and dump site for long enough that it was already threatening the city’s water supply. In 1922, engineers at the Water Department of Cleveland did tests of the city’s drinking water to respond to claims that the water tasted medicinal or like carbolic acid. Their findings: “The polluted water of the Cuyahoga River reached the water works intakes, and this polluted water contained the material which caused the obnoxious taste.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/40/49405e40-f0a6-42f4-8a13-b64fffd102e2/cuyahogariverfire-press-48fire_1e1b539f07.jpg)

Everyone knew the river was polluted, but nobody much cared. If anything, it was a badge of honor. As David Newton writes in Chemistry of the Environment, “Fundamentally this level of environmental degradation was accepted as a sign of success.”

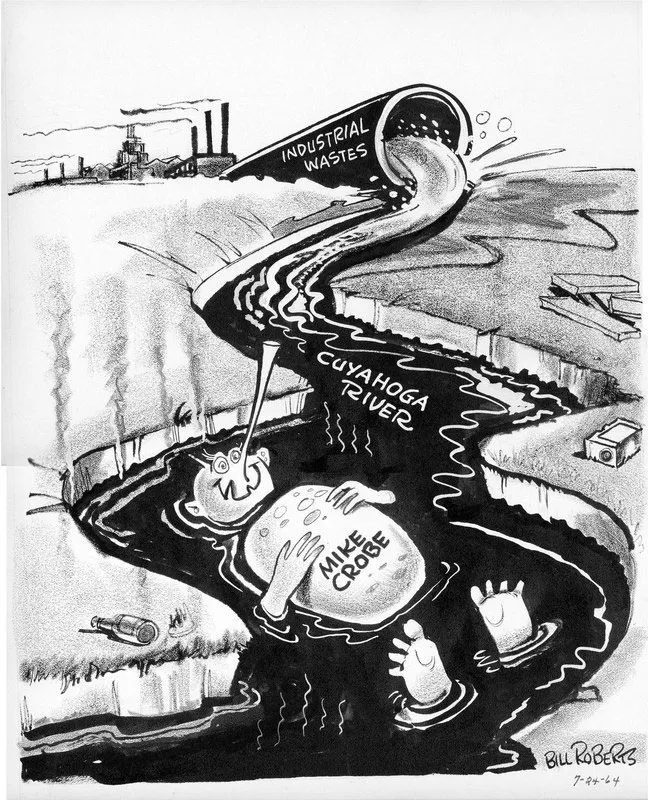

In 1868, 1883, 1887, 1912, 1922, 1936, 1941, 1948 and 1952 the river caught fire, writes Laura La Bella in Not Enough to Drink: Pollution, Drought, and Tainted Water Supplies. Those are some of the incidents we’re aware of; it’s hard to say how many other times oil slicks may have ignited, as press coverage and fire department records were both inconsistent. But not all the fires were as innocuous as that of 1969. Some caused millions of dollars’ worth of damage and killed people. But even with the obvious toll on the landscape, regulation of industry was limited at best. It seemed more important to keep the economy booming, the city growing and people working. This attitude was reflected in cities around the country. The Cuyahoga was far from the only river to catch fire during the period. Baltimore, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Buffalo and Galveston all used different methods to disperse oil on their waters in order to prevent fires.

But the tide began to turn in the 1950s, according to the Stradlings. Between 1952 and 1969, Cleveland lost about 60,000 manufacturing jobs. Deindustrialization took hold alongside the Civil Rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War. “Over the years, Clevelanders were hardly complacent about the burning river, but not until the 1970s did they begin to think of its meaning in anything other than economic turns,” the Stradlings write. “That the Cuyahoga fire evolved into one of the great disasters of the environmental crisis tells us something about Americans’ growing suspicion of industrial landscapes, a suspicion encouraged by the decreasing benefits they derived from such places.”

By 1968, the city was actively trying to clean up the river. That year, voters approved a $100 million bond program to fund cleanup, and the city attempted to improve its sewage system so as not to pollute the lake. After the 1969 fire, Cleveland’s mayor Carl Stokes, the first African-American elected to the position in any major American city, worked with his brother, Louis, in Congress to push for environmental regulation. Though the '69 fire was relatively small, the two brothers helped shape public perception of it as a turning point.

“The story goes that it was the 1969 river fire that directly led to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency, but I think it was a little bit more complicated than that,” says Rebekkah Rubin, a public historian who collected oral histories for the 50th anniversary of the fire. “But for people who weren’t paying much attention to environmental advocacy, it’s easy to get behind the cleanup of a river that’s on fire.”

Over the years, the river transformed from a dump site to a place for recreation. Today, Rubin sees people on the river kayaking, fishing and cruising on stand-up paddle boards, though she admits that such recreations are still not available to everyone in the city. “The river doesn’t flow through the neighborhoods that tend to be more low income and more segregated, but I think it should be a resource available for all Clevelanders.”

Despite its new life, the river still shows signs of its former degradation. In 2018, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that EPA scientists tested dozens of sites along the river bottom and found that polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) levels remain dangerously high. Other scientists have cautioned that the river is still “burning” with viruses, bacteria and parasites, including Salmonella, Clostridium, enteroviruses, Giardia and hepatitis A. But even with these remaining issues, the Cuyahoga is unrecognizable compared to what it was a mere 50 years ago—as is the case with numerous waterways around America.

Donovan, who today works as the director of the nonprofit Canalway Partners, has spent years working to build a path along the Cuyahoga River Canal that will make it more accessible to all Cleveland residents. He sees the river differently now, as if it and the city have undergone an identity crisis and are now settling into their new roles. “As the river gets cleaned up, entertainment options become more viable,” Donovan says. “Nobody is going to be sitting on a river with bloated rats floating by. It reflects the changing perception of what’s important here.”

And for Donovan and Rubin alike, it’s a change worth celebrating, even if there’s still work to be done.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)