In the middle of the course, over that flying mile, Mickey Thompson’s speed was about equal to the muzzle velocity of a bullet fired from a lightly loaded small-caliber pistol: 406.60 miles per hour. This was September 9, 1960, on the Bonneville Salt Flats. He became the fastest man in the world that day, the first American to go over 400 mph, the fastest racer ever on land. Unofficially, at least.

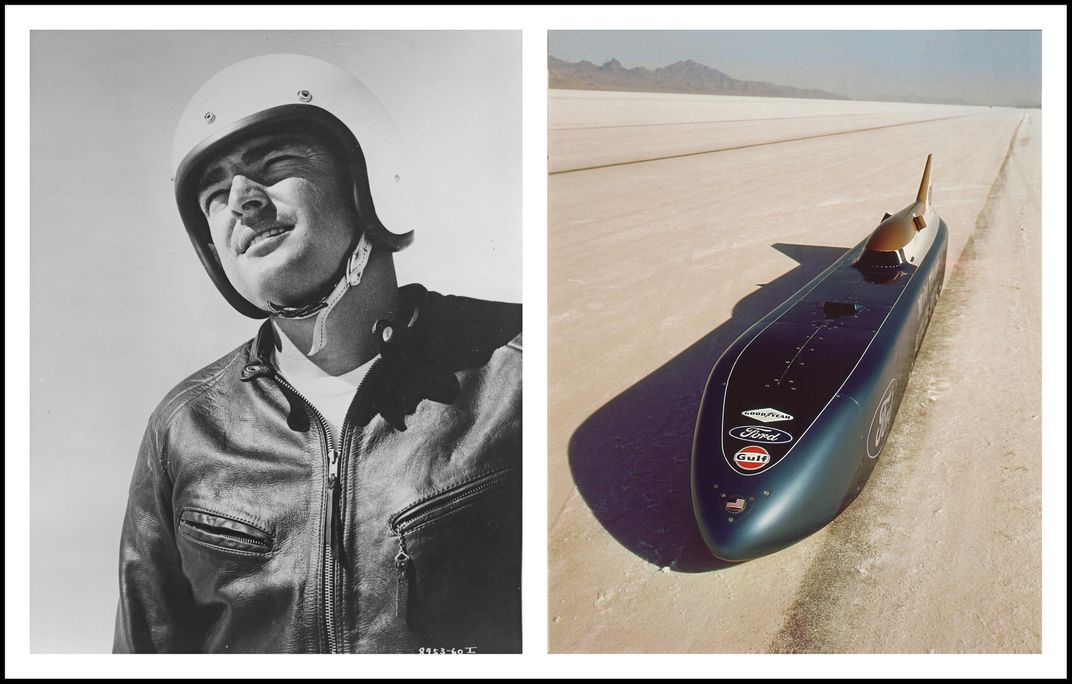

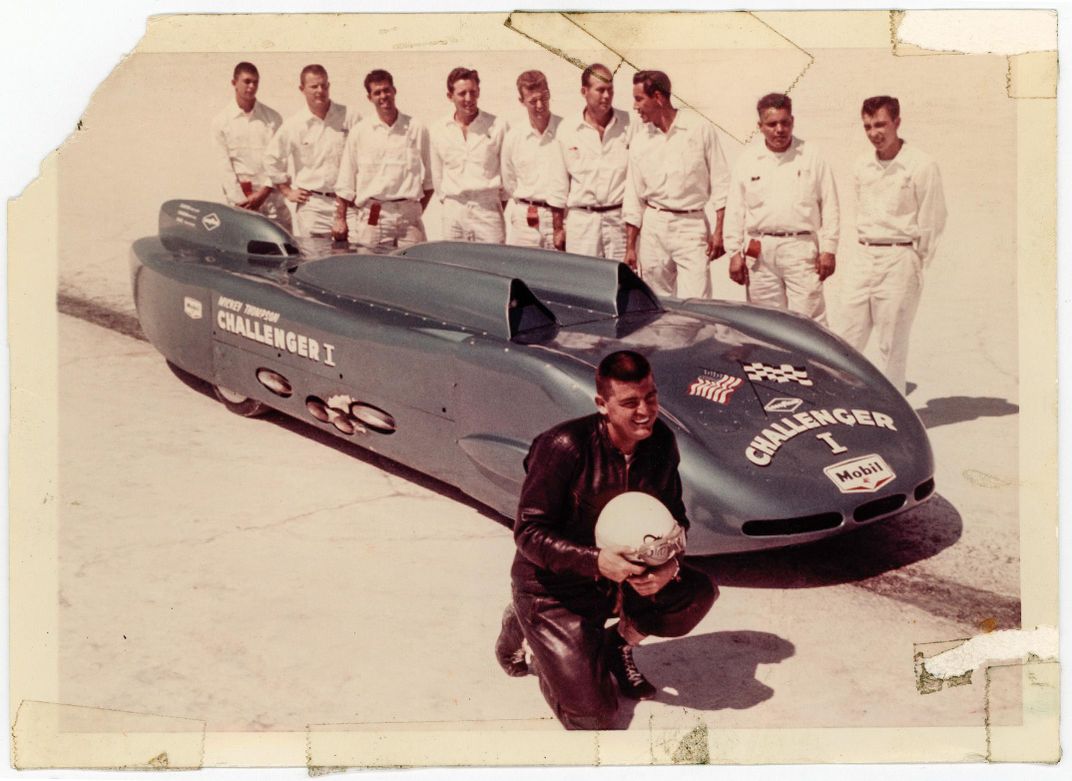

Because to earn the world land speed record, the car has to make two passes. Thompson’s car—the Challenger, an 8,000-pound, 3,000-horsepower streamliner with four V-8 engines he’d chalked out on the garage floor, then built with his own hands—broke on the return run. But neither fame nor glory nor pride nor patriotism are bounded by the rule books, and that afternoon, under that high Utah sky, Mickey Thompson became a by-God American hero in the last great age of the black-and-white newsreel.

* * *

In the middle of nearly the same course, over that same flying mile, under that same Utah sky, Danny Thompson’s speed was even higher than his father’s: 448.757 mph. This was August 12, 2018, on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Danny became the fastest piston-driven man in the world that day. Officially. Thompson’s Challenger 2—a 5,200-pound, 6,000-horsepower dagger with two V-8 engines, built by his father’s hands and by his own—did not break. It made both runs successfully. But neither fame nor glory nor pride nor patriotism are bounded by the rule books, and Danny Thompson remained not very famous, even as he surpassed his father, the murdered American hero from the last great age of the black-and-white newsreel.

This is the story of Mickey Thompson and Danny Thompson and a car. And OK, right off the top the whole deal feels like something out of ancient Greece, or Norse mythology, or maybe Hollywood—too big, too on the nose. Too Shakespearean. All vengeance and reckoning, the son takes up the blade of the fallen father—the murdered king—to honor and make whole and right the great man’s fame.

Right: At the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1968, Challenger 1 sits at guide lines–oil emulsion marks that reduce driver disorientation in the glaring white landscape. ThompsonLSR

The truth of Thompson father and Thompson son and that impossibly beautiful car is as old as storytelling. But it’s not Sophocles or Wagner. It’s not even Inigo Montoya. It’s the Beach Boys or Jan and Dean, a kind of a piston ring cycle, a sunshot folk opera set in Southern California and on the western slope of Colorado and under that huge blue Utah sky. And because this is an imperfect world, filled with greed and violence, even the blinding high-noon dazzle of those snow-white Salt Flats can’t drive out the shadows and the ghosts and the darkness at the heart of the story.

Still, this isn’t as much about justice or revenge or even closure as it is about a family of racers, racing. Not a reckoning. A reconciliation.

When they’re running for speed on the flats, you can hear those engines Dopplering downrange from everywhere in the valley, howling so that even miles away there’s something mournful in all that sunlight. And every car and every driver and the whole crazy story of speed and desire echoes down the years until it all feels like centuries ago. Because the car is an arrow across time.

* * *

Marion Lee “Mickey” Thompson was the hottest hot rod king America ever made—and he remade America in return. Born in 1928 in Southern California, he arrived at the right place in the right moment to ride the first crest of America’s postwar car madness.

Not much of a student, he was an uncanny natural with cars. He was building them in the backyard from junk parts before he was old enough for a driver’s license. He’d run them at Muroc Dry Lake bed. Flat-out, straight-line speed stuff. In the old snapshots he’s a sharp-featured pale kid with an angle-iron crew cut in cuffed dungarees and a white T-shirt—the hot rod genius who barely finished high school as poster boy for all that tire-smoking, go-fast SoCal excess. Big engines! Wide tires! Street rods were a kind of high-performance folk art after the war, a symbol of sudden working-class prosperity and mobility and hell-for-leather freedom. In Mickey Thompson all those big American ideas found individual expression in street racing, drag racing, road and off-road racing. He was the hotshoe Paul Bunyan, a young giant out on a new frontier.

This is back when hot rods and rock ’n’ roll were noisy evidence of social decay and juvenile delinquency, of decadence and premarital sex and parental disrespect. Which is how Hollywood framed it in movies like Rebel Without a Cause.

All of which is important to remember when you get to the Mickey Thompson biographies. Earnest, well-meant and well-considered, they’re generally straight-line stuff, too. They get you from A to B to C well enough, but if you really want insight into Mickey Thompson man and myth, you have to find his “autobiography.” It’s a slender little thing, from 1964, long out of print. The full title is Challenger: Mickey Thompson’s own story of his life of Speed—capital “S”—and the cover states Thompson wrote the book “with” automotive and racing historian Griffith Borgeson.

The life of Speed may be Thompson’s, but the voice of the book is surely Borgeson’s. Written in the gloriously over-the-top style of the early 1960s motoring press, it is not only a florid sort of instep-kicking, aw-shucks Lives of the Saints, but an entertaining whitewash of the American garage—historically a fairly profane corner of American life. It also glosses, or worse, makes colorful, Thompson’s habit of punching in the nose those he disagrees with. The book turns out to be a position paper on hot rodding, too, and getting fast cars off the street and onto the drag strip.

So here’s Mickey Thompson, black haired and black tempered, a two-fisted precisionist and self-taught horsepower obsessive who could, would, will, can build anything, drive anything, trial-and-error anything—and then beat you flat with it.

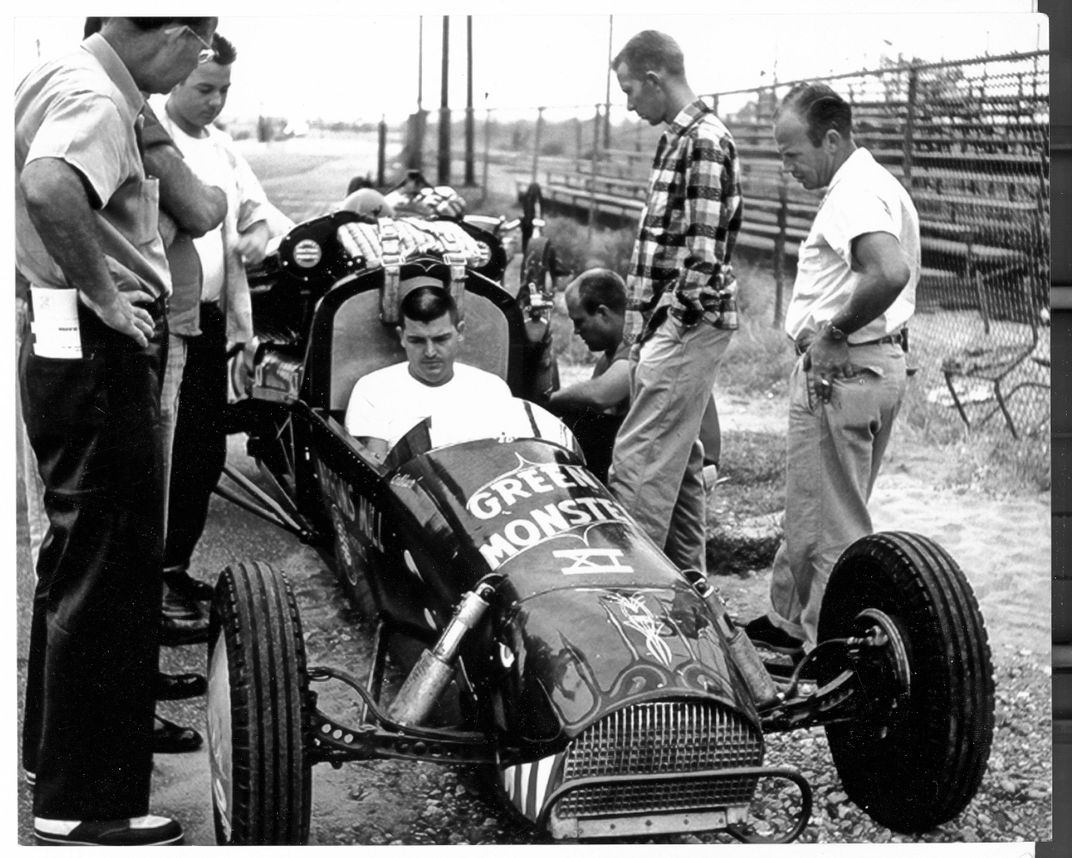

He’s no hoodlum. In fact he takes a job as a pressman at the Los Angeles Times to help pay for all the racing and engine building. He rarely sleeps. At night he makes the newspaper and during the day builds the cars. And manages a drag strip. And raises a family. His wife, Judy, cleans the house and feeds the kids and dry-fits the pistons on the engine rebuilds before he gets home. She’s a motorhead, too, and the children, Lyndy and Danny, daughter and son, are racers from the cradle. The whole racer family caught in dad’s planetary wheel spin. They spend every weekend in the station wagon on the way to the drag strip, to the track, to the high dry desert. He doesn’t invent drag racing but he helps perfect it. Mickey dreams up a thing called the slingshot dragster—a quarter-miler with the driver seated behind the rear axle for better traction.

Keep in mind he’s also racing sedans and open-wheelers out at Riverside racetrack, and down in Long Beach, and driving the length of Mexico in the deadly, legendary Carrera Panamericana. He’s always looking for an edge—or maybe the edge itself. He’s making a name for himself driving, and building and selling speed parts to the other gearheads. He’s well known in Southern California.

Until he wraps a small body around a pair of V-8 engines to make an extraordinary dragster, just for the hell of it. Just to see what it can do, and maybe find out how fast is fast. Turns out to be so fast, more than 266 mph, it makes him the fastest American ever. And now it’s got him the way it got all the others: the hunt for the world land speed record, out there in the distant shimmer.

* * *

The first official fastest man on earth was a Frenchman, Count Gaston de Chasse-

loup-Laubat, driving a Jeantaud battery-electric car. Just before the turn of the last last century, in 1898, he zoomed along at an incredible 39.25 mph. Après that, the deluge.

The count launched a timeline of dreamers from that day to this, daredevils and scoundrels on the deserts and beaches of Belgium and England and France, Australia and Africa, California and Utah and Florida, aristocrats and paupers, stuntmen and grease monkeys, pump jockeys, cowboys and knights of the realm. They ran chain-driven steamers, buzzing electrics and repurposed 12-cylinder aircraft engines as big as garden sheds. Some were beautiful, some were laughable—men and machines, both—some were streamlined and some no more aerodynamic than a brick.

The cars became as famous as the drivers. The Fiat Mephistopheles. The Bluebird. The Chitty Bang Bang. The Green Monster. The Mormon Meteor. The Spirit of America. Henry Ford himself held the record for a couple of weeks in 1904 at 91.37 mph driving the Arrow.

The world’s first fastest woman was Dorothy Levitt, a Brit, who drove 91 mph in 1906. By the time World War I had come and gone, the idea of a land speed record had caught the imagination of the modern world, like the race to the poles or a flight across the Atlantic. Every record was a headline. Every record made the newsreels. (So did the failures and the crashes and the fatalities. Broken cars and drivers were scattered on the sands of every continent.)

For decades, the British were best at it. Between the wars, Sir Malcolm Campbell was the 20th-century Prometheus. He set record after record in his magnificent Bluebirds, each bigger and faster than the last. He went west to Bonneville and south to Daytona and year after year speeds rose as

records and his competition fell away.

After World War II cars and drivers were flirting hard with 400 mph, but no one had done it yet. Certainly no American. Through the 1950s the British, wearing their immaculate lab coats and carrying their clipboards and slide rules, continued their million-pound-sterling factory mega-projects, each car the product of wind-tunnel research and cutting-edge design and engineering. Meanwhile, the Yanks were building backyard streamliners out of war surplus belly tanks.

Into which world swaggers one Marion Lee Thompson, who then does what only Thompson can do. After that twin-engine dragster of his runs so fast, he hustles home, grabs a piece of chalk, draws the outline of a low, wide quad-engine streamliner on his garage floor. And starts to build. He takes four castoff Pontiac V-8 engines and bends a frame around them, then wraps the whole thing in bodywork so snug his crew has to push him down into the seat like a jack-in-the-box. If it doesn’t kill him it might make him famous. He calls it Challenger, paints it blue, hitches up the trailer and heads for Utah. He wears old-time motorcycle leathers and a crash helmet like a daredevil being shot from a cannon, goggles and an oxygen mask straight out of Fahrenheit 451. All of which at these speeds is a kind of prayer. The frame is what saves you, the roll cage, the Fates.

He fires the engines and 1,000 feet away you feel the sound as a bad pressure in your chest. The course across the salt is about ten miles long depending on weather and the season, and razor straight. They measure the flying mile right in the middle. It takes four miles just to get the car up to speed, and you can hear it roaring down the whole valley under that impossible cerulean sky, the entire horizon perfect white and absolute blue as heaven’s own threshold.

Here’s Mickey Thompson in his own words—or at least Griffith Borgeson’s—to describe it:

People often ask how I can shift all four of those transmissions at once, and how the linkage is made that makes it possible. When I laid the car out, I didn’t attack all four gearboxes at once. I took on one, told myself that it had to work and made it work. Then the next one had to work, so I made brackets and linkage that made it work too. And I kept going that way until all four were linked up and working together. I have a knack for sensing optimum leverage points.

I have one lever for low and high gears. You pull it all the way back low and push it forward for neutral. When you’ve done that, another lever falls right into your hand. You push it forward, in the same plane, and you’re in second. Then you pull it back, grab the first lever again, pull it back and slightly to the side and you’re in top gear. It’s not too much different from shifting a passenger car, as anyone who has heard Challenger run can tell.

I blasted off and the car felt wonderful. I waited for tires to break loose and they didn’t. The biggest problem had always been getting up to 300 soon enough, which I never had been able to do. But this morning everything clicked and I could bear down with my throttle foot.

Through the seat of my pants I sensed the tire diameters and they were all perfectly uniform it seemed, right to the thousandth of an inch. I felt for the clutches and they were locked solid, as they should be. I listened to all the sets of gears and they all sang in one precise key. I felt out for the distribution of weight from front to rear and it was perfect.

I checked the two tachometers that spoke for the fore and aft pairs of engines. I never had been able to get them to follow each other perfectly. This morning they did. At 300 they were indicating identical revs. I stayed on the throttle and at 350 they still were together. Yes! At 375 they told me that the front engines and the rear engines, front wheels and rear wheels still were turning at the same, identical rate. I still stayed on the throttle and Challenger went like a dream. No more handling problems at all. The car finally was sorted out and I had the combination that worked. For the first time I didn’t have to lift my throttle foot.

Long before I rolled to a stop I knew that I’d broken 400 and while we refueled and Judy and Fritz and the whole gang were bursting with joy, the official time came over the field phone: 406.60 MPH.

Fastest man alive, but to make it official, he has to turn the car around in under an hour and drive back the other way. The average of those two runs will be what gets him into the record book. The car breaks. Something in that impossible Rube Goldberg sequence of engines and linkages gives way.

He doesn’t hold the official record, he’s not certified—but in those grainy black-and-white film clips he’s the fastest man alive and he’s an American driving American equipment.

It didn’t kill him. So it makes him famous.

The story is all blue sky and bootstraps so far.

* * *

Picture 1960 America as a gleaming TV sitcom kitchen of that time, bright with the latest labor-saving appliances and Formica and chrome. A tidy aspirational reflection of the new middle class to which we—or at least television advertisers—aspired. Now picture Mickey Thompson crashing through that kitchen wall in his fire-breathing supercar.

Without even setting the official record, Mickey Thompson becomes a national sensation—the flip side of America’s prim, postwar, suburban self-image. He is brash, fearless, inexhaustible. He is sleepless, ingenious, ambitious. He can’t stop himself. He designs cars on cocktail napkins; keeps a notepad in bed—you never know when you’ll need to sketch out some shock absorber schematics. It’s not just street rod magic now, either. It’s big-ticket sponsorships and factory deals with Detroit. The year before he had left the Los Angeles Times. He builds open-wheel racers to challenge the old guard at the Indianapolis 500. He builds off-road racers to challenge the deserts of Baja California. He builds a national speed parts business and a national tire business. He builds another car to challenge the world land speed record. He builds a series of stadium truck races. Mickey Thompson builds a Mickey Thompson empire. He’s an engineer, a manufacturer, a driver, a promoter, an impresario. It’s hard to sensationalize him, because he’s so straight-up sensational.

Out of the 1960s and into the 1970s and ’80s, Mickey Thompson is as big a name as there is in motorsports. He grows out the crew cut, gets divorced, remarries. The collars get a little wider, and so does he, but the determination and innovation never flag. He’ll beat you every which way and any way he can. Remember, this is all happening across the same arc of history that gets us from Benny Goodman to Woodstock to Prince, and from Korea to Khe Sanh to the surface of the moon. Mickey Thompson is supremely adaptive. From success to success—and, more important, failure to failure—he manages to thrive.

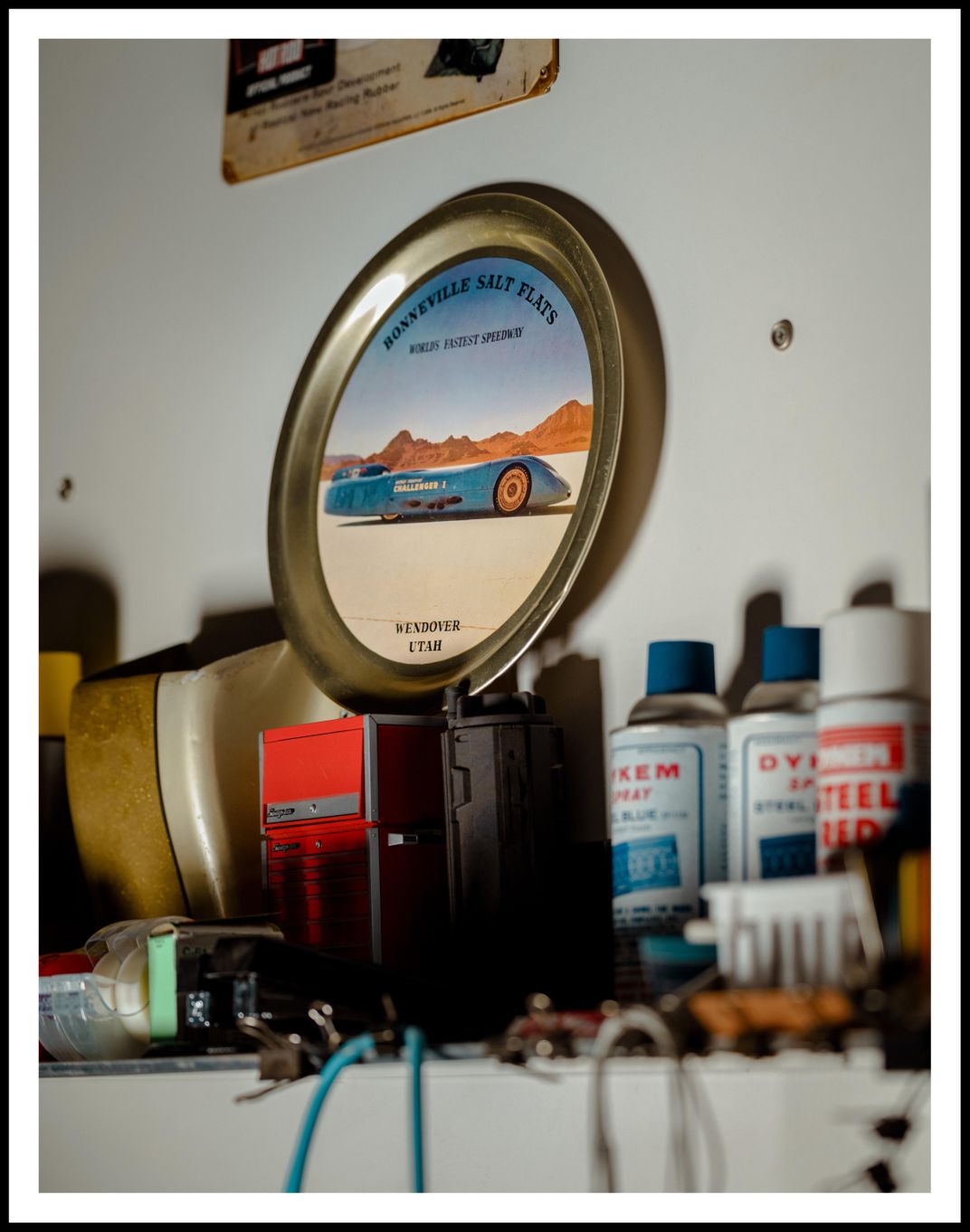

So even when he’s not, the public thinks of Thompson as the fastest American ever. By 1965 jet power dominates the world land speed record, and American Craig Breedlove holds the absolute record at 600-plus mph in the Spirit of America Sonic 1. So Thompson puts his streamliner on the trailer and heads back to the Salt Flats in 1968. Not because he can outrun a jet, but because he’s Thompson. A lighter car, narrower, twin-engined fore and aft, with a body like the fuselage of a wingless fighter plane, the car can still win the official piston-driven record. But he’s rained out. As has been rumored, only God can stop Thompson. The car goes into storage.

By the mid-1980s, he’s too busy, even by his own overachieving standards, so he takes on a partner for the stadium race events. Imagine the Los Angeles Coliseum decked out as a winding dirt track for off-road trucks, with tight turns and spectacular jumps and whoop-de-dos and mud flying and the noise and the crashes and the beer sales and you’ll see it. It’s a fan favorite from the first green flag.

The partner is Michael Goodwin, a successful, charismatic former concert promoter who runs a supercross series nearly identical in its appeal and specifications to Thompson’s truck series: stadium dirt tracks and high-speed racing with lots of thrills. Two wheels instead of four. They’ll run their two companies together. Goodwin will take over some of the administrative chores. On paper it’s a match made in heaven.

From the beginning there’s trouble. Goodwin is a tall, smart, look-at-me type with a line of grandstanding rock ’n’ roll patter. Thompson would still rather build something than brag about it. They’re at odds immediately.

Within the first few months Thompson realizes that Goodwin isn’t paying out what the company owes—to Thompson or to anyone else. Goodwin stonewalls. Thompson sues. Goodwin takes the case all the way to the California State Court of Appeals. He loses. He owes Thompson more than half a million dollars, all of it gone, unaccounted for. He declares bankruptcy. This takes years.

In a different story, with different characters, maybe that’s where the matter ends. A court ruling and a money judgment, and all the lawyers shake hands, because business is business, even after a bankruptcy. Happens all the time.

Not this time.

* * *

Danny Thompson answered his phone early on the morning of March 16, 1988. “Somebody from my Dad’s office called and said, ‘Something’s happened up in Bradbury. We don’t know what it is.’” Danny drove fast up the freeway from Huntington Beach and found his father’s street cordoned off. The local news helicopters were hovering overhead. Mickey Thompson, famous American racer, 59 years old, and his second wife, Trudy, 41, had been shot to death in their own driveway. It was a tabloid celebrity murder in the old SoCal style, a preamble to O.J., all that grainy aerial video and the telephoto newspaper images from 1,000 feet away.

There’s money and jewelry conspicuous at the scene. It’s not a botched robbery. It’s a hit, an assassination. The neighbors hear the shots and the screaming and witness two men fleeing down the hill—on bicycles.

For days Thompson had been warning his family about Michael Goodwin’s subtle and not-so-subtle threats. Of revenge, of violence. “He’s taking everything I’ve got. He’s destroying me,” Goodwin told two friends at a 1988 dinner, according to court documents. “I’m going to take him out.” But there was no case against Goodwin, no physical evidence he had anything to do with the murders.

Years passed. It was perhaps the most famous cold case in America.

Investigators came and went from the Los Angeles police and the county sheriffs and the district attorney’s office and got nowhere. But Collene Thompson Campbell, Mickey’s sister, the politically astute former mayor of San Juan Capistrano, never gave up. She kept pressuring the authorities for better, broader, deeper investigations. She wouldn’t let anyone forget. A re-canvassing of the original witnesses eventually revealed what seemed like an unrelated comment from years earlier. A man matching Goodwin’s description had been seen parked on the street near the Thompson home in Bradbury several days before the killings.

That was enough to reopen the case. The trial began in November 2006. In January 2007, a Los Angeles County jury convicted Michael Goodwin on two counts of first-degree murder, for having engineered the murders-for-hire of Mickey and Trudy Thompson. He was sentenced to consecutive life sentences. His 2015 appeal was denied, and he remains at the Richard J. Donovan State Prison in San Diego, California. The gunmen have never been found. Or even identified.

In 1988 Mickey had wanted to dust off Challenger 2 and rewrite the record books with the Thompson name. He had even asked Danny to drive the car for him. He was murdered a month later.

* * *

What do you do when your own father is a character out of American mythology? How long is the shadow he casts?

Danny Thompson is a racer. It’s in his blood. You’re born with it. You’re stuck with it. It’s indefinable, the one thing you can never outrun—an identity as much a matter of chromosomes as of character. It is a psychospiritual condition in which you hear exhaust noise as music and connect to the physical universe with hands at 10 and 2 and with an increasing pressure exerted at the tip of the right big toe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/14/4714b83c-b321-41cd-9005-df8c1a3bf5b0/cone__dt_diptych.jpg)

Right: Setting the speed record, Danny Thompson says, took “five decades and a lot of elbow grease.” Mark Mahaney

Danny Thompson is his father’s son. So Danny raced. Motocross, formula cars, off-road buggies and trucks. He was good at it, too, won a lot of races. Won championships. Of course the irony is Mickey forbade it. From the time he yanked Danny out of a quarter-midget racer at the age of 9 or 10, Mickey was adamant that Danny not race for a living. Mickey understood too well the dangers. Refused to sponsor him or help him in any way. So for a long time, Danny Thompson raced in secret.

They were close, but both were stubborn and headstrong. You see the family album now, the two of them getting the boat ready to go water-skiing; or leaning on the fender of a car, and you see Mickey Thompson, American icon and force of nature, standing with a slender kid wearing a shy half-smile.

That’s why it felt like the end of one thing and the beginning of another, a new chapter for the whole family, when Mickey asked Danny to drive the second Challenger.

Danny can be hard to read. He’s pretty intense, like his old man. But unlike his father he reminds himself not to be. He doesn’t have to live up to a public persona, the way Mickey did. So he’s often a little on guard—against himself. He is smart and funny and charming and can play pugnacious, but you can see why he inspires not only loyalty, but devotion and love from his team of builders and fabricators and mechanics, most of whom are volunteers. They helped him rebuild the car that his father first built in 1968.

Sitting in the kitchen, the second thing you notice is that he has hands like a blacksmith. The first thing is that he has a boy’s face. Not boyish, but the wide smile and clear eyes of a boy, lined and grown old.

He is an artist with a welder’s torch and a press brake and the big industrial cutters and benders out in his shop. And that’s part of all this, too, the aesthetic of the car, the beauty of it, that rare and perfect alignment of form and function. You know immediately what this car is meant for. By comparison, all other cars, passenger cars especially, are compromised by convention or intention or cost. In that way every car is somehow expressive of its imperfections.

And it has to be said here that there’s something holy about the American road, about driving, in the purity of speed and distance, out where the world can’t catch you—not only in the absence of responsibility as Kerouac or Twain or Steinbeck suggest—but in velocity itself. Not just freedom or forgiveness, but absolution, even grace. In many ways you’re only ever trying to outrun yourself.

So even today, high in the western mountains of Colorado, Danny keeps his guard up.

“I mean the guy’s in jail for a double life sentence, and 154 years and whatever it is. But he still has enough money stashed where he can hire, you know. You can get a lot of stuff done from jail. So, are we still cognizant of all of that here today? People coming in and out? Uh, yeah. Is it, am I worried about it happening? I don’t think so. I wouldn’t be first on the list, but I would be second on the list.”

Who’d be first?

“Collene. My aunt. My dad’s sister.”

* * *

They start early at Bonneville, when it’s cool and the air is dense. It can be lonely on the flats at sunrise, and the Bonneville shadows are hundreds of feet long.

But there’s a strange serenity inside your helmet for a few seconds too, even in that tunnel of noise, even in that Old Testament thunder there’s something very still, something fixed and unmoving and quiet and perfect and for a moment you’re entirely, utterly free, free of people and their needs and their complications, free of appetite and anger and despair, free of joy and ambition, politics and money and love, free even of fear and hate, the whole mad world spinning away beneath you like a lathe until all at once and at last you are free of yourself.

By the time you recognize any of this stillness, it’s gone.

Danny wears a high-tech synthetic firesuit and gloves and boots and a space-age helmet. But the frame is what might save him, the roll cage and the belts and the Fates.

* * *

The car.

The car!

The car is an amazement.

The car is perfect.

Five decades ago it was on the leading edge of automotive technology. Today, it’s a museum piece. It looks now as it did then, a long, low blade of deepest blue. To run your hand over it is to understand its purpose. When Danny Thompson runs his hand over it, he understands his own.

The car is 32 feet long. Twenty-seven inches high at the tip and 37 inches at the cockpit canopy. It is 34 inches wide. Fueled, it weighs 5,700 pounds. The engines are dry blocks, so the cooling is done by the fuel. Almost every part of the car is hand-built and custom-made. The fuel lines are as complicated as a circulatory system. A single run gulps down 50 gallons of an 87 percent nitromethane, 13 percent methanol fuel blend. The car’s weight drops by about 500 pounds over the course of a single one-way pass. The car is now powered by a pair of Hemi V8 engines built by Richard Catton. Horsepower has more than doubled, to 3,000 per engine. Twin three-speed gearboxes link the two engines. The car does not have computerized traction control. “It has Danny control,” Danny says.

Each engine drives one set of wheels. The front engine is mounted backward in the chassis. The only way to stop a car this fast is dual parachutes. The car is also equipped with carbon ceramic disc brakes, but you’d burn them up without the parachute assist.

When Mickey Thompson built the car in 1968, Sports Illustrated called it “a rolling textbook in sophisticated automotive design.” When his son finished rebuilding it 50 years later, he saw and felt his father in every part. The same chassis, the same aerodynamics, and the same hand-formed aluminum skin on the car’s featherweight body.

Right: Damage to a Challenger 2 tire shows the punishing stresses inflicted during Thompson’s 439 mph run during Speed Week 2017. Mark Mahaney

And here’s my favorite note from the Thompson LSR tech web page:

“The tires are a prototype nylon weave backed with banded steel. There is only 1/32 of an inch of rubber. Any more would spin off due to heat and expansion. They are custom made by Mickey Thompson Tires.”

Remaking and reimagining the car took nearly a decade and every nickel Danny and his wife, Valerie, had.

Built in 1968 by the father, rebuilt for 2018 by the son.

Danny paints it blue, hitches up the trailer and heads for Utah. His crew has to push Danny down into the seat like a jack-in-the-box. Danny calls it Challenger 2.

* * *

This is Danny Thompson in the Bonneville Racing News, Issue 192.

The starter gives us the go signal and I feel the push truck touch the car. I release the brake and apply some throttle, the truck pushes me up to only 10-15 miles an hour, the clutches engage and the car pulls away in first gear. There is always a lot of exhaust and mechanical noise in the car and I can hear or sense it through my earplugs and helmet. The car is pretty heavy at 5200 lbs. and I accelerate as hard as possible, sensing wheel slip and modulating the throttle. I don’t want to burn up the expensive Mickey Thompson tires with too much wheel spin—their treads are very thin!

Down the course I go, faster and faster. At about 270 mph, I’m at redline. We use about 6900 rpm since these A Fuel engines have such enormous torque, there is no reason for more. I have a red light to signal me to shift, and then I touch the air-shifter button on the steering wheel and both gearboxes shift perfectly at whatever amount of throttle I’m using, according to traction and wheel slip conditions. I continue in second gear, faster and faster, the course is flying past. At about 350 miles per hour I’m at the top of second gear and button the air shifter again to get high gear. On we go to whatever speed we can get by the end of the five-mile SCTA course! After I clear the course, I shut the fuel off to kill the engines and pop the safety chute to slow the car down as quickly as possible, since the hand brake shouldn’t be used until we get down to about 175 mph. But I don’t normally need to use it until I almost stop. All four wheels have powerful carbon-carbon disc brakes, and in an emergency chute failure I could use them at higher speed, at the cost of eating up the pads and then discs.

* * *

In the video of the record run you can watch Danny Thompson save his own life when the car gets sideways at about 400 mph. He recovers it by steering calmly into the skid—slow hands, just like a driver’s ed film—then saves it again by correcting back the other way. Turn up the audio and you’ll hear the wheel slip, too. He’s skating on the salt in a 6,000-horsepower missile, feathering the throttle and hands light on the yoke, the earth and sky rushing up at him, the whole world a blur but somehow known in every vector and direction through the seat of the pants, acceleration and yaw and thrust calculated and recalculated without conscious thought in the racer brain, input and output unthinking and instantaneous. A gesture as pure as any ever made by a Zen master.

Right: A timing tag from the Southern California Timing Association verifies Danny Thompson’s record-setting 448.76 mph run at the Bonneville Salt Flats. Mark Mahaney

Cars like the Challenger 2 and the other Salt Flats piston-driven streamliners are curiosities now, artifacts, the last stand of an ancient world, the end of all that antique fire and thunder. As much art as archaeology.

Danny’s two-way record in the resurrected Challenger 2 stands at 448.757 mph. The current Outright World Land Speed Record was set more than 20 years ago by a British turbofan twin jet-powered car, the ThrustSSC: 763.035 mph. Faster than the speed of sound. But Danny Thompson has the fastest piston-driven car in history, just the way his father wanted it.

* * *

Even here at Bonneville, though, on what looks like the threshold of heaven, there’s no such thing as universal justice. Danny scoffs.

“I wanted to kill the guy myself. That wasn’t going to bring my dad back. So even when the guy went to jail and everybody said—what do they call it—oh now you have closure. No. Closure would be my dad sitting there instead of you. You know that would be closure. So it didn’t bring any closure at all.”

Sometimes mythology lets us down. There’s no vengeance, no final celestial reckoning, no kingdom of the absolute. No peace. Instead there’s this. Another photograph. It’s a snapshot of Danny Thompson and that dazzling car under a high azure sky. Right after the record run. He’s smiling. Tired but radiant, that boy’s face grown old is grown young again with a look of something even deeper than relief. He’s done what he came here to do, what he was sent here for.

He’s been set free.

:focal(5047x3571:5048x3572)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/21/9121e9d6-2de6-40ed-b23c-9e7e9478e7d8/julaug2019_a11_dannythompson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)