The Daring Journey Across Antarctica That Became a Nightmare

Everyone knows about Robert Scott’s doomed race to the South Pole in 1911. But on that same expedition three of his men made a death-defying trip

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/5f/415f7a85-2407-4f1e-9a1c-c72cdd612a3f/dec2017_a03_antarctica.jpg)

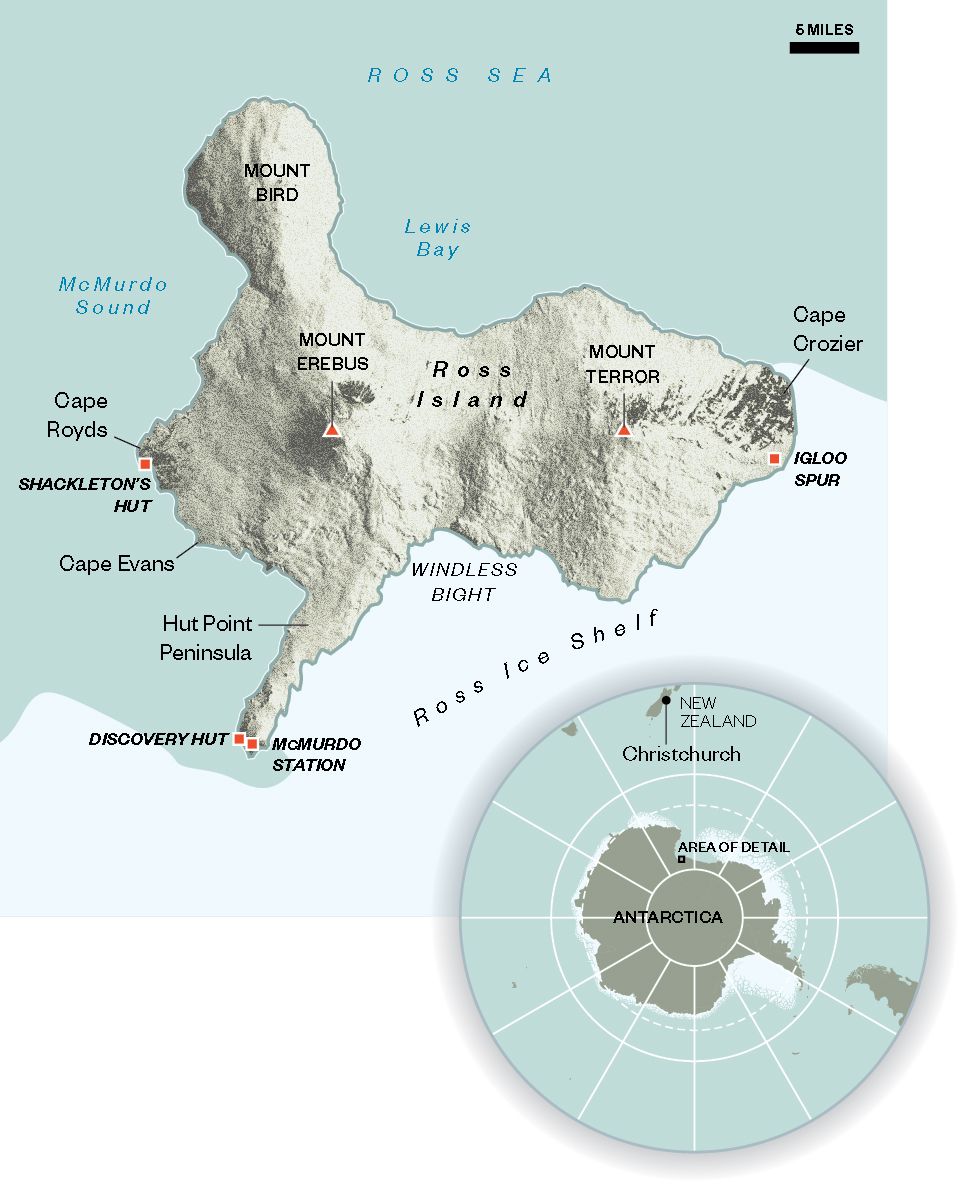

Flying to Antarctica from New Zealand is like changing planets. Five hours south from Christchurch, inside the giant windowless cylinder of a C-17 jet, and you step out onto white ice that extends to the horizon in all directions. A bus ride takes you over a black hill into an unexpectedly large collection of warehouses and miscellaneous buildings, clustered on the black volcanic rubble at the end of Hut Point Peninsula, Ross Island. That’s McMurdo Station, home every Antarctic summer to around a thousand people. I found the big Galley in the middle of town to be the same warm and sociable place it had been on my last visit 20 years before. I was happy to discover its cooks have now agreed to offer pizza 24 hours a day, less happy to find that all the dorm rooms in town have TVs.

I was returning to visit the historic sites left by some of the earliest expeditions. Like many devotees of Antarctica, I remain fascinated by these first visitors to the Ice, who in the early 20th century invented by trial and error (lots of error) the methods they needed to stay alive down there. Some of their huts have been beautifully preserved by New Zealand’s Antarctic Heritage Trust, so it’s easy to see their accommodations and marvel at their primitive gear. The huts stand in the summer sun like gorgeous statues.

The Discovery Hut, built in 1902 by Robert Scott’s first expedition, is located on the outskirts of McMurdo, and looks like an 1890s prefab Australian veranda bungalow, which is exactly what it is. Ernest Shackleton’s 1908 hut, located 28 miles north of McMurdo at Cape Royds, feels as neat as a modern alpine cabin. Shackleton had been part of Scott’s first expedition, when he clashed with Scott; he came back in 1908 with lots of ideas about how to do things better, and his hut shows that. It overlooks a colony of Adelie penguins, and scientists who study these tough, charming birds live next to the hut every summer.

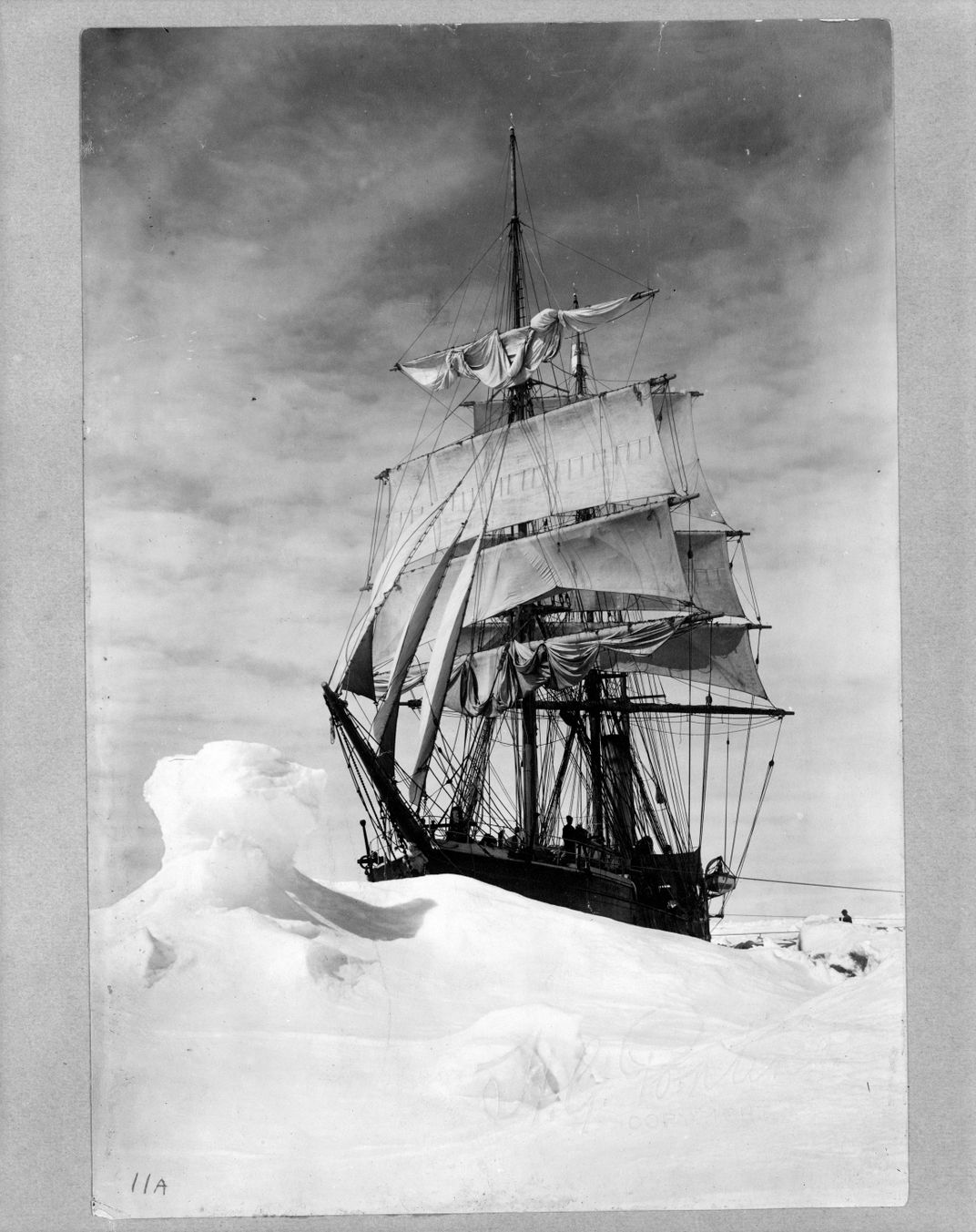

About halfway between those two dwellings, on Cape Evans, is the hut that is the clear champion of the three in terms of its aura, stuffed as it is with furniture, equipment, clothing, boxes of frozen food, and stories. This 25- by 50-foot prefab wooden building served as the base for Scott’s second expedition, from 1910 to 1913. Those years were crowded with incidents ranging from farce to tragedy, and they were all recorded in a book, The Worst Journey in the World, written by a junior expedition member named Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Since its publication in 1922, this great memoir has become a beloved masterpiece of world literature. It has been called the best adventure travel book ever.

The Worst Journey in the World

In 1910 – hoping that the study of penguin eggs would provide an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles - a group of explorers left Cardiff by boat on an expedition to Antarctica. Not all of them would return. Written by one of its survivors, “The Worst Journey in the World” tells the moving and dramatic story of the disastrous expedition.

You might think the “Worst Journey” of the title refers to Scott’s famous failed attempt to reach the South Pole, which killed five people. But it primarily refers to a side trip that Cherry-Garrard made with two other men. How could that journey be worse than Scott’s doomed effort? The explanation is not terribly complicated: They did it in the middle of the polar winter. Why would anyone do something that crazy? The answer is still important today, in Antarctica and elsewhere: They did it for science.

**********

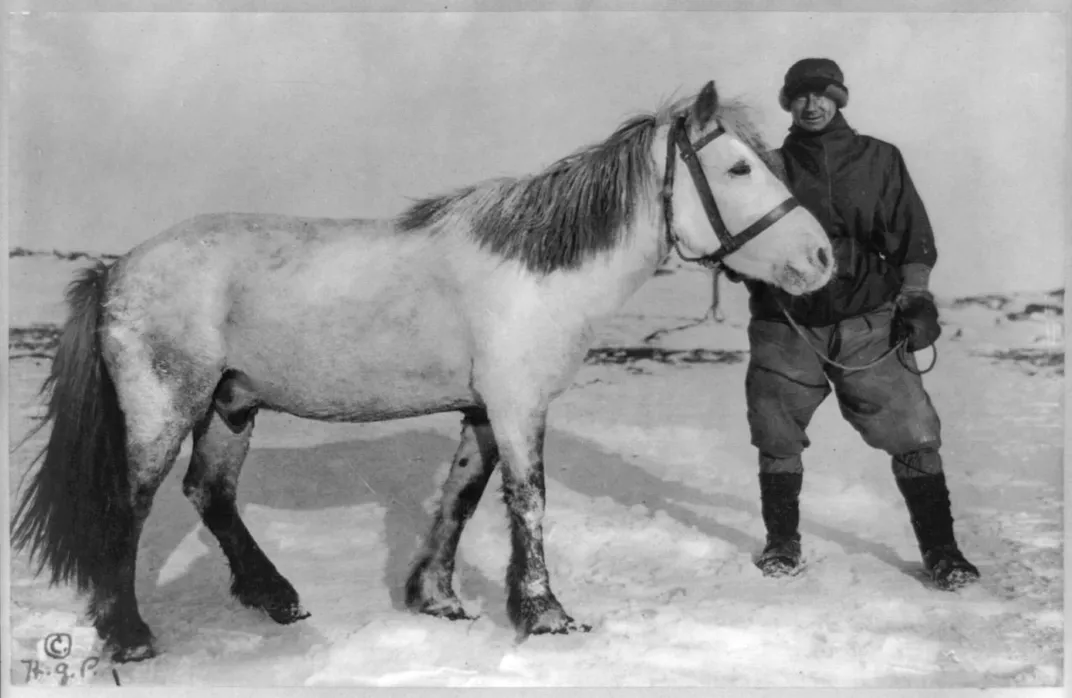

By June of 1911 Scott’s shore team of 25 men had already been at Cape Evans for half a year, but their attempt on the pole couldn’t start until October, when the sun returned. So they settled into the hut to wait out the winter, passing the dark frigid days cooking meals, writing a comic newspaper, giving lectures, and exercising the dogs and ponies by the light of the stars.

On June 27 Scott’s second-in-command, Edward “Bill” Wilson, took two companions, marine lieutenant Henry “Birdie” Bowers and zoological assistant Cherry-Garrard, out with him on an attempt to reach Cape Crozier, at the other end of Ross Island, about 65 miles away. They were going to man-haul two sledges, 130 miles round trip, through the winter darkness, exposed to the coldest temperatures that anybody had ever traveled in, approaching 75 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. They would leave the scale of human experience—literally, in that sometimes it was colder than their thermometers could register.

That Scott would allow Wilson to do this seems foolish, especially given their primary goal of reaching the South Pole. Even in the Antarctic summer, their first season of explorations had been a parade of mistakes and accidents, and though no one had died, several had come close, and they had accidentally killed 7 of their 19 Siberian ponies. Cherry-Garrard’s account of this preparatory summer reads like the Keystone Kops on ice, with people getting lost in fogs, falling into crevasses, drifting away on ice floes and dodging attacks by killer whales. Given all those near catastrophes, the winter journey was a truly terrible idea—dangerous at best, and a potential end to the polar attempt if things went wrong and the three never came back.

But the science side of their expedition was real. Unlike Roald Amundsen’s group from Norway, in Antarctica at the same time specifically to reach the pole (which it would do a month before Scott’s party), the British expedition had dual motives. Sponsored by the British Royal Geographical Society, it included 12 scientists who were there to pursue studies in geology, meteorology and biology. Reaching the pole was clearly the main goal for Scott, and even for his sponsors, but they also wanted to be understood as a scientific expedition in the tradition of Charles Darwin aboard the Beagle, or James Cook. Their hut at Cape Evans resembled a Victorian laboratory as much as it did a naval wardroom. Even today the hut is jammed with antique instruments and glassware.

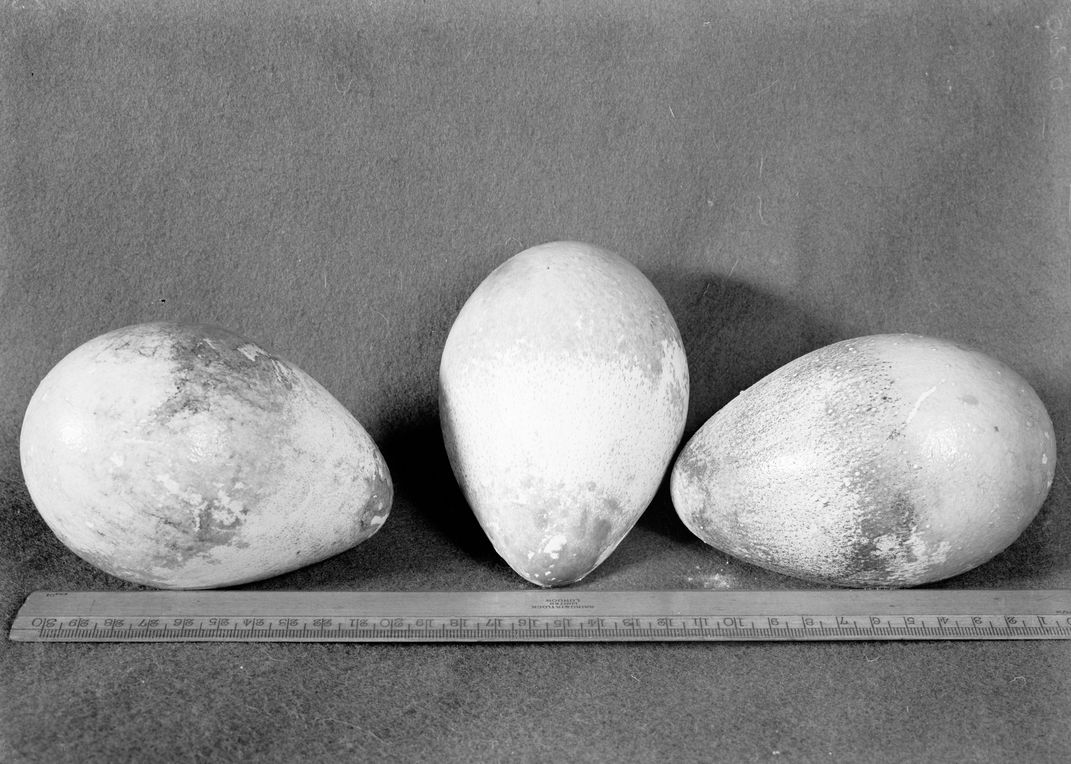

Wilson was their chief scientist, specializing in birds. When he and Scott earlier explored Ross Island during the Discovery expedition, they had found a colony of emperor penguins at Cape Crozier, and learned that these birds lay their eggs only in midwinter. So when Scott asked Wilson to join him again in 1910, Wilson agreed on the condition that he be allowed to make a midwinter trip to obtain penguin eggs. It was important to Wilson because the eggs might shed light on some pressing questions in evolutionary biology. If the emperor penguin was the most primitive bird species, as it was thought to be, and if in fact “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” to quote the then famous notion that each embryo grows through the evolutionary history of its species, then penguin chicks still in the egg might reveal tiny reptilian scales developing into feathers, supporting both theories at once. To Wilson, then, this was a scientific opportunity like those Darwin had seized in his era. It was far more important to him than reaching the South Pole. Understanding this, and wanting him along for his capable leadership and friendly company, Scott agreed to let him try.

**********

Very soon after Wilson and his companions departed their cozy hut for Cape Crozier, it became obvious that hauling sledges through the perpetual Antarctic night was truly a bad idea. Darkness itself was a big part of the trouble. Cherry-Garrard was near-sighted, and in the cold his glasses frosted over, but without them he was effectively blind. The other two had to lead, but even with normal eyesight they couldn’t see much, and fell into crevasses fairly often. They stayed roped together so that when one dropped into a crack the other two could haul him back up. This system worked, but it was always a rude shock and a gigantic effort.

Another problem was that the snow was so cold it often failed to cohere. Their loaded sledges each weighed nearly 400 pounds, and the runners sank into this sandlike snow. They had to drag one sledge at a time, then hurry back to get the other one before a wind came up and blew their tracks away, which might cause them to lose one or both sledges in the dark. More than once they worked to and fro like this all day for a total forward gain of less than two miles.

The warmest temperatures topped out at minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit. Only their intense exertions kept them from freezing in their tracks, but even so it’s hard to understand how they avoided frostbite in their hands, feet and faces. Somehow they carried on. Cherry-Garrard wrote that he was acutely aware of the absurdity of their efforts, but he did not mention that to the others. He was the youngster, at 25, and Wilson and Bowers, 38 and 28, were like older brothers to him. Whatever they did he was going to do.

For three days a storm forced them to wait in their tent; after that, they worked all day for a gain of about a mile and a half. Every morning it took them four hours to break camp. They began with a meal of biscuits and hot pemmican stew, eaten while lying in their reindeer-hide sleeping bags. Getting into their frozen outer clothing was like muscling into armor. When they were dressed, it was out into the icy darkness to take down their Scott tent, a four-sided canvas pyramid with a broad skirt that could be well-anchored in the snow. When all their gear was piled on the two sledges, they started the day’s haul. Bowers was the strongest of them and said he never got cold feet. Wilson monitored his own feet and often asked Cherry-Garrard how his were doing; when he thought they were getting close to frostbite, he called a halt, and as quickly as possible they put the tent up, got their night gear into it and made a hot dinner of pemmican stew. Then they tried to get some sleep before they became too cold to remain in their bags.

Nineteen days of this reduced Cherry-Garrard to a state of benumbed indifference. “I did not really care,” he wrote, “if only I could die without much pain.”

Finally they rounded a curve of cliffs and saw by starlight that they were east of Mount Terror. Cape Crozier had to be near. They had used five of their six cans of stove fuel, which boded poorly for the trip home. When they came to a low ridge running off the side of Mount Terror, they trudged up it to a volcanic knob next to a flat spot. Loose rock was essential to their plan, so they stopped there to make their local base camp. Wilson named the place Oriana Ridge, after his wife. Now it’s called Igloo Spur, and the little shelter they built there is called the stone igloo, or Wilson’s rock hut.

This rock hut was something they had planned back at Cape Evans. It was going to be their living quarters, which would free up their Scott tent to serve as a lab space for examining and preserving their penguin eggs. In the rock hut they would burn seal or penguin fat in a blubber stove, thus saving their last can of stove fuel for their return. The walls of this rock hut were to stand about waist high, in a rectangle large enough to fit the three of them side by side, with space to cook at their feet. The doorway would be a gap in the lee wall, and they had a length of wood to use as a lintel over this gap. One of their sledges would serve as a roof beam, and they had brought along a big rectangle of thick canvas to use as the shelter’s roof.

We know they planned this rock hut carefully because Wilson’s sketches for it survive, and also, there’s a practice version of it still standing at Cape Evans. Very few people have noticed this little rock structure, and it’s never mentioned in the expedition’s histories or biographies, but there it stands, about 30 yards east of the main Cape Evans hut. Scott wrote in his diary on April 25, 1911: “Cherry-Garrard is building a stone house for taxidermy and with a view to getting hints for making a shelter at Cape Crozier during the winter.”

I hadn’t even noticed the little stone structure during my visit to Cape Evans in 1995, but this time, startled to realize what it was, I inspected it closely. It’s impressively foursquare and solid, because Cherry-Garrard took a couple of weeks to build it, in full daylight and comparative warmth, using Cape Evans’ endless supply of rocks and sand. Its neat walls are three stones wide and three to four stones tall, and crucially, gravel fills every gap between the stones, making it windproof. It’s perfectly squared off, with drifted snow filling its interior right to the brim.

On Igloo Spur, conditions were vastly different. They worked in darkness and haste, after 19 days of exhausting travel. And it turned out there weren’t that many loose rocks on Igloo Spur, nor hardly any gravel. The lack of sand had the same explanation as the lack of snow: Wind had blown anything small away. As it happens, Ross Island forms an immense wall blocking the downslope winds that perpetually fall off the polar cap, so air rushes around the island to east and west, creating an effect so distinct it is visible from space: The whole of Ross Island is white except for its west and east ends, Cape Royds and Cape Crozier, both scraped by the wind to black rock. The three men had inadvertently camped at one of the windiest places on earth.

Their hut ended up having thinner walls than the practice version, and with no gravel to fill the gaps between stones, it was almost completely permeable to the wind. In his memoir, Cherry-Garrard’s dismay is palpable as he describes how even after they spread their canvas roof over these walls, and piled rocks on the roof and its skirt, and slabs of ice against the sides, the shelter was not as windproof as their tent. As soon as they lay down inside it, they stuffed their spare socks into the largest holes on the windward side, testimony to their desperation. But there were many more holes than socks.

When this imperfect shelter was nearly finished, they made a day trip to collect their emperor penguin eggs. Reaching the sea ice from this direction, which no one had ever done before, turned out to require descending a 200-foot cliff. The climb was the most harrowing technical mountaineering any of them had ever attempted, and they undertook it in the dark. They managed it, though getting back up the cliff almost defeated them. Cherry-Garrard, climbing blindly, smashed both of the penguin eggs entrusted to him. With a final effort they made it back to Igloo Spur with three eggs still intact. The next day they completed the rock hut and erected the Scott tent right outside its doorway, in the lee of the shelter. Three weeks after setting out, everything was arranged more or less according to their plan.

Then a big wind hit.

**********

They huddled in their drafty shelter. Wilson and Bowers decided the wind was about Force 11, which means “violent storm” on the Beaufort scale, with wind speeds of 56 to 63 miles an hour. There was no chance of going outside. They could only lie there listening to the blast and watching their roof balloon off the sledge and then slam back down on it. “It was blowing as though the world was having a fit of hysterics,” Cherry-Garrard wrote. “The earth was torn in pieces: the indescribable fury and roar of it all cannot be imagined.”

It was their tent that gave way first, blown off into the darkness. This was shocking evidence of the wind’s power, because Scott tents, with their heavy canvas and broad skirts, are extremely stable. The same design and materials are used in Antarctica today, and have withstood winds of up to 145 miles an hour. I’m not aware of any other report of a Scott tent blowing away. But theirs was gone—the only shelter they had for their trek back home. And their canvas roof continued to bulge up and slam down. As the hours passed all the stones and ice slabs they had placed on it were shaken off. Then with a great boom the thick canvas tore to shreds. Blocks of the wall fell on them, and the ribbons of canvas still caught between stones snapped like gunshots. They had no protection now but their sleeping bags and the rock ring.

In this moment Bowers threw himself across the other two men and shouted, “We’re all right!”

Cherry-Garrard wrote, “We answered in the affirmative. Despite the fact that we knew we only said so because we knew we were all wrong, this statement was helpful.”

Snow drifted onto them and gave them some insulation. As the storm raged, Wilson and Bowers sang songs, and Cherry-Garrard tried to join them. “I can well believe that neither of my companions gave up hope for an instant. They must have been frightened but they were never disturbed. As for me I never had any hope at all.... Without the tent we were dead men.” It was Wilson’s 39th birthday.

Finally, after two days, the wind relented enough to allow them to sit up and cook a meal. They crawled outside, and Bowers, while looking around north of the ridge, came on their lost tent, which had collapsed like a folded umbrella and fallen in a dip between two boulders. “Our lives were taken away and had been given back to us,” Cherry-Garrard wrote.

The irrepressible Bowers suggested they make one more visit to the penguin colony, but Wilson waved that off and declared it was time to leave. They packed one sledge with what they needed and headed for Cape Evans.

**********

Forty-six years later, in 1957, the first person to revisit their rock hut was none other than Sir Edmund Hillary. He was in the area testing snow tractors with some fellow New Zealanders, preparing for a drive to the pole, and they decided to retrace the Wilson team’s “astonishing effort,” as Hillary called it, as a test of their tractors. A paperback copy of Cherry-Garrard’s book was their guide, and eventually Hillary himself found the site.

Hillary expressed surprise that the three explorers had chosen such an exposed spot, “as windy and inhospitable a location as could be imagined.” In his typical Kiwi style he judged their shelter “unenviable.”

He and his companions took most of what they found at the site back to New Zealand. There were over a hundred objects, including the second sledge, six thermometers, a tea towel, 35 corked sample tubes, several envelopes and a thermos, which the three men must have lost and left behind by accident, as it would have been useful on their trip home.

The sledge is now displayed high on the wall of the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, in a stack of other sledges; you can’t see it properly. The other items are in storage. Helpful curators have let me go into the back rooms to inspect these relics. I found it a strange and moving experience to heft their lost thermos, unexpectedly light, and to contemplate one of their long Victorian thermometers, which measured from plus 60 degrees to minus 60, with zero right in the middle.

**********

On their return to Cape Evans, the explorers’ sleeping bags became so iced up they couldn’t roll or fold them. To lie in them was to lie in a bag of little ice cubes, but this was nevertheless not as cold as staying exposed to the air. Hauling the sledge was the only thing that warmed them even a little, so they preferred that to lying in the tent. At first Wilson wanted them to sleep seven hours at a time, but eventually he shortened it to three. They began to fall asleep in their traces as they hauled.

Pulling only one sledge made things easier, but as they ran low on fuel they ate less, and had less water to drink. They could see Castle Rock and Observation Hill getting closer every day, marking the turn to Cape Evans, but they were on the verge of collapsing. Cherry-Garrard’s teeth began to crack in the cold.

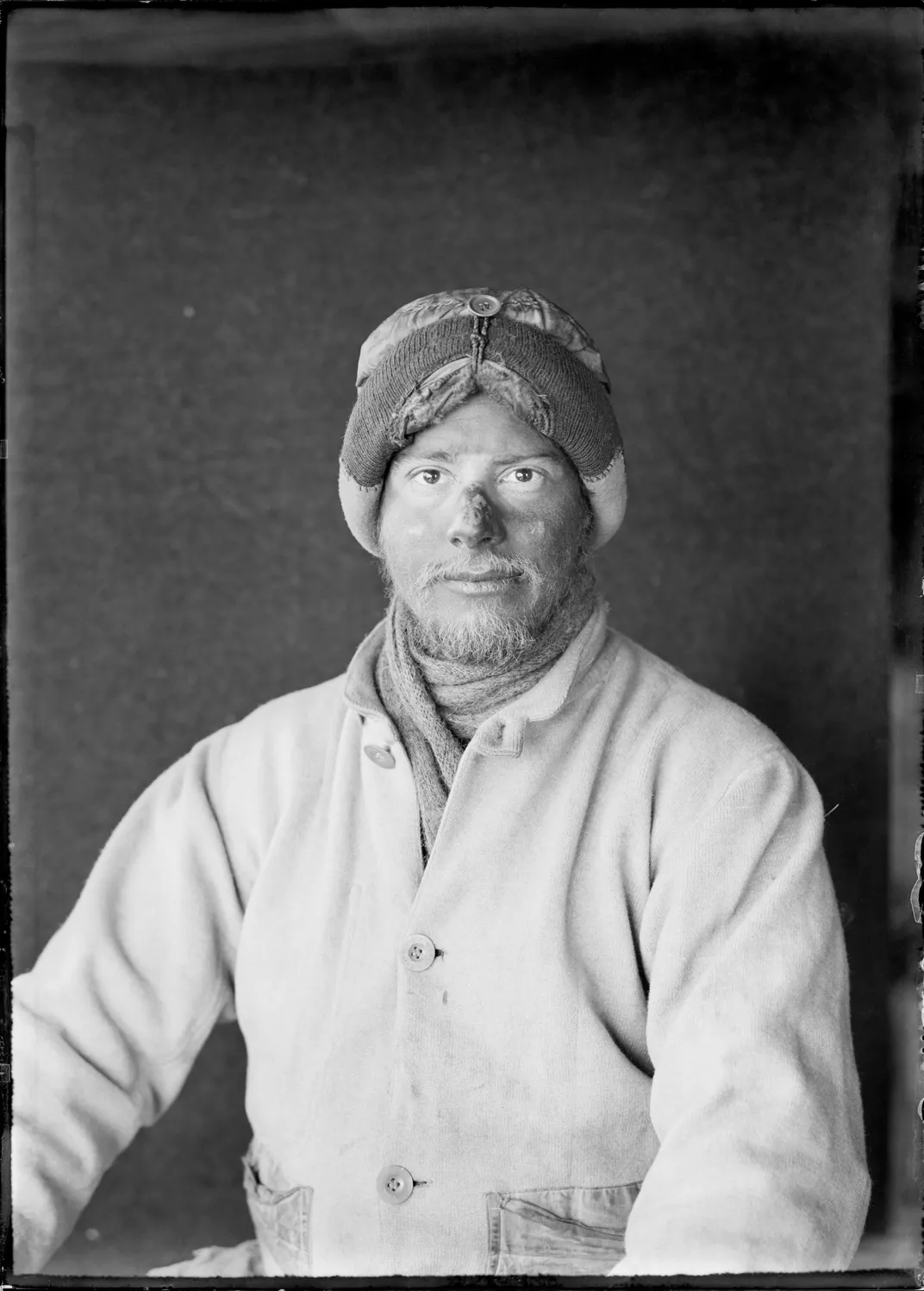

Eight days after leaving Igloo Spur, and 35 days after starting their trip, they crashed back into the Cape Evans hut. Their clothes had to be cut off them. After they were dressed and cleaned up, they sat down at the long table that still fills the hut, and the expedition’s photographer, Herbert Ponting, took their picture. It was one of those lucky shots that caught them like an X-ray: Wilson grimly aware he had almost gotten his friends killed; Cherry-Garrard stunned, traumatized; Bowers knocking back a mug as if he had just returned from a stroll round the corner.

**********

When the sun returned three months later, Scott and 15 men took off for the South Pole, including the three winter travelers, though scarcely recovered from their ordeal. Scott had organized the attempt such that supply depots for the return trip were left at regular intervals, and teams of four men then headed back to Cape Evans after each supply load was deposited. Scott decided who to send back depending on how well he thought they were doing, and it was a crushing blow to Cherry-Garrard when Scott ordered him to return from the next-to-last depot, high on Beardmore Glacier.

Cherry-Garrard was already back at Cape Evans when a party came in with the news that Scott had begun the last leg of the trip with five men rather than four, changing his plan at the last minute and wrecking all his logistics. Very possibly this was the mistake that got the final five killed, because all the food and stove fuel had been calculated to supply only four.

For the men waiting at Cape Evans, there was nothing they could do through that long dismal winter of 1912. Cherry-Garrard went out the following spring with a final sledge-hauling group, one that knew the polar team had to be dead but went looking for them anyway. In a snow-drifted tent just 11 miles south of One Ton Camp, the nearest depot to home, they found three bodies: Scott and Cherry-Garrard’s two companions from the winter journey, Wilson and Bowers.

**********

Cherry-Garrard returned to England, drove ambulances in the Great War, got sick in the trenches and was invalided out. Living in isolation on his family estate in Hertfordshire, it’s clear he was suffering from what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder.

Asked by the organizing committee to write an official account of the expedition, he struggled with the job until George Bernard Shaw, a neighbor and friend, suggested that he plumb the depths of the story as he had lived it. Years of effort followed that helpful advice, and finally he published his book, in 1922. In it he achieved a prickly ironic style, its somber intensity leavened with a strong dash of dark humor. He quoted liberally from his comrades’ diaries, so that people like Wilson and Bowers became distinct speakers in their own right. Inevitably the book served as his memorial to his friends, and though he refrained in classic stiff-upper-lip style from expressing his grief directly, every page is suffused with it. In some places it suddenly pops off the page, as during his description of the discovery of the polar party’s frozen bodies, which consists mostly of excerpts from diary entries written at the time. “It is all too horrible,” he wrote at the end of that terrible day. “I am almost afraid to go to sleep now.”

Near the end of the long chapter describing the winter journey, he summed up the feeling of their last hard slog home:

“How good the memories of those days are. With jokes about Birdie’s picture hat: with songs we remembered off the gramophone: with ready words of sympathy for frost-bitten feet: with generous smiles for poor jests....We did not forget the Please and Thank you, which mean much in such circumstances, and all the little links with decent civilization which we could still keep going. I’ll swear there was still a grace about us when we staggered in. And we kept our tempers—even with God.”

**********

Most of my stay in McMurdo was over before I got to Igloo Spur, occupied as I was by training classes and visits to the historic huts, and by flight cancellations caused by high winds. I began to worry that the rock hut on Cape Crozier was destined to remain the one that got away. Then the call came, and I hustled down to the helo pad in my extreme weather gear. My guide, Elaine Hood, appeared, and we were off.

The helicopter ride from McMurdo to Cape Crozier takes about an hour, and is continuously amazing. Mount Erebus, an active volcano first sighted by the Ross expedition in 1841, steams far above you to the left, and the snowy plain of the Ross Ice Shelf extends endlessly to the south. The scale is so big and the air so clear that I thought we were flying about 30 feet above the ice, when actually it was 300. On the day we flew, it was brilliantly sunny, and the Windless Bight was windless as usual, but as we circled the south side of Cape Crozier and started looking for the rock hut, we could see snow flying over the exposed rocks.

Then we all spotted the little rock circle, right on the edge of a low ridge that was black on the windward side, white on the lee. Our pilot, Harlan Blake, declared he could land, but for safety’s sake would have to keep the helo’s blades spinning while we were on the ground. He approached the ridge from downwind, touched down, and I jumped out, followed by Elaine. The wind knocked her over the moment she was exposed to it.

She got up and we staggered to the stone ring, struggling to stay upright. Later Harlan said his gauge marked the wind at a sustained 50 miles an hour, with gusts of 65. It roared so loudly over the ridge that we couldn’t hear the helicopter running only 50 yards away. I circled the ring and tried to see through the thin skeins of drift raking over it. Its walls were tumbledown and nowhere more than knee high. Runnels of snow filled its interior space, channeled by the many holes peppering the windward wall. I spotted one of the socks stuck between those stones, and a whitened piece of wood that might have been the door lintel. The three men would certainly have been jammed in there; I took four big steps along the short sides of the oval, five along the long sides.

The view from the ridge was immense, the sunlight stunning, the wind exhilarating. I tried to imagine keeping your wits about you in a wind like this one, in the dark; it didn’t seem possible. Confused and scattered though I was, I still felt sure we were at a holy place, a monument to some kind of brotherly craziness, a spirit I could feel even in the blazing sunlight. The wind brought it home to me, slapping me repeatedly with what they had done: Five days here in the howling night, in temperatures maybe 60 degrees lower than the bracing zero that was now flying through us. It was hard to believe, but there the stone ring lay before us, shattered but undeniably real.

Elaine was taking photos, and at one point I noticed she was frosted with blown snow. I gestured to her and we returned to the helo. Harlan took off and we circled the ridge twice more looking down at it, then headed back to McMurdo. We had been on Igloo Spur for about ten minutes.

**********

Cherry-Garrard ends his book with these words: “If you march your Winter Journeys you will have your reward, so long as all you want is a penguin’s egg.”

For a long time I used to think this was a little too pat. Now that I’ve visited Antarctica again, I think Cherry-Garrard said exactly what he wanted, not just here but everywhere in his beautiful book, because the penguin’s egg he referred to is science, and the curiosity that fuels science. It’s not about being first to get somewhere; it’s about falling in love with the world, and then going out in it and doing something wild with your friends, as an act of devotion. There’s a rock ring out there on Cape Crozier that says this with vivid force.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.