How Much Has the Town Where the Scopes Trial Took Place Evolved Since the 1920s?

Each July, Dayton, Tennessee, celebrates its role in the famous court case with a re-enactment and festival

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/ea/20ea60e6-0673-414f-9749-8e45db690111/apr2016_h06_evoscopes.jpg)

Bobby Beard runs his clippers over an imposing but largely bald head, leaving behind a gray-white fuzz, short and tight as a cap of worn velvet. We’re looking here at years and years of experience, perseverance and endurance. This barber is 74 and his customer 90. “Bobby ain’t great at cuttin’ hair,” confides the customer. “When he gets to playin’ music, he’ll trim one side of your scalp and let the other go.” When not barbering—or sometimes when he is—Beard plays the most mournful pedal steel guitar in Dayton, Tennessee.

On this July morning, the sun beats heavily through the shop’s front window. “Isn’t it incredible that our planet rotates around the Sun, which throws out all that heat and light?” marvels Beard. “The Sun didn’t just pop out from nothing. Somebody had to put it there. The universe is like a seed you sow in the ground and grows into a tomato plant. The amazing thing is God grew the universe in less than a week.”

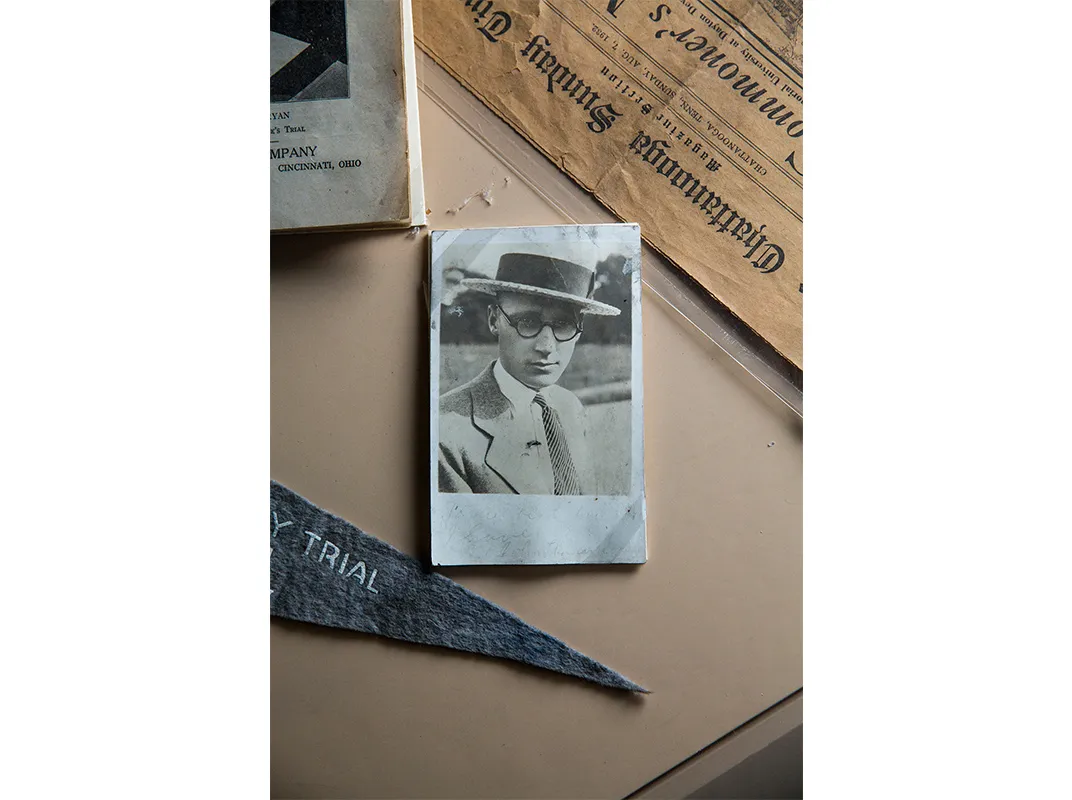

Such a bold statement of belief is very much in keeping with local history. Beard’s barbershop looks out on the lawn of the Rhea County Courthouse, where Daytonians are currently gathered for the annual Scopes Trial Festival. The sky is a crisp, clear blue. A dozen or so people are milling around the steps of the building, where, some 90 years ago in the sweltering summer heat, two celebrity advocates debated Darwinism before standing-room-only crowds. A dozen more visitors are scattered around the statue of the fiery orator William Jennings Bryan (once known as “the Great Commoner”), who died in town of a heart attack five days after the trial ended.

Anyone who has seen the 1960 film Inherit the Wind is familiar with the basic story: John Scopes, a sports coach and science teacher at Dayton High, was charged with breaking a new state law that banned the teaching of evolution. He was convicted and fined $100, though the verdict was later overturned on a technicality (the judge, rather than the jury, had determined the penalty). It’s unclear whether Scopes actually taught evolution at all: Dayton’s business leaders enlisted him, in an effort to promote their town, after the American Civil Liberties Union offered to bankroll the defense of any teacher who broke Tennessee’s new law.

Pretty much every summer since 1988, this tiny Appalachian town (pop. 7,200) has roused itself to celebrate that publicity stunt gone viral. The Scopes Trial Festival, held over two weekends in July, features live bluegrass, tractor and craft shows, and a fried-Oreo food truck. A storyteller spins his tales like a barker at a sideshow. The centerpiece of the festival is a town-commissioned musical, Front Page News, which re-enacts the trial in the vast courtroom where it was held.

The play, performed by members of the nearby Cumberland County Playhouse, is essentially a rebuttal to Inherit the Wind. The Hollywood version of the trial is widely loathed in Dayton, and Front Page News does hew much more closely to the court transcript. Director Jim Crabtree says the local production is “about tolerance and respect for those whose beliefs differ from our own.” Yet the actors playing the Yankee characters tend to squawk and snivel, while those playing Southerners—some of whom are careful to pronounce ‘‘evolution’’ so that the first syllable comes out ‘‘evil’’—are courtly, courteous, even judicious. Periodically, the entire cast suddenly puts the action on hold and stands in a row to sing hymns. Though the audience is encouraged to shout “amen” just as real spectators did in 1925, the earnest two-act play lacks the carnival atmosphere of the movie. At times, it seems longer and windier than the actual trial. The production survives on the brio of its bluegrass numbers and the enthusiasm of its actors. Subtlety isn’t their forte. Rick Dye, who played the suspender-snapping Chicago defense lawyer Clarence Darrow in 2015, emitted an air of overwhelming vanity combined with some unspecified nastiness. George Miller as Bryan presented the fundamentalist position with the thoughtful dignity of a fruit peddler. Even so, it’s quite remarkable to watch them pace the same creaky plank floors, sit at the same oak desks and argue before the same jury box as those two splendid litigators.

The lawyers were what made the trial front-page news. Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate and a believer in the literal Bible, volunteered to help the prosecution as part of his campaign against atheists and agnostics. “Darwinism is not science at all,” he maintained, “it is guesses strung together.” Fearing the incursion of pious fanaticism into education, Darrow volunteered to lead the defense. His strategy was to secure his client’s conviction, then appeal to a higher court so the statute could be ruled unconstitutional. But his coup de théâtre was to call Bryan to the stand as an expert witness on the Bible.

It’s generally accepted that during the cross-examination, Bryan came off as a buffoon. He got testy when Darrow grilled him about the whale that swallowed Jonah—“You don’t know whether it was the ordinary run of fish or made for that purpose?”—and the exact date of Noah’s flood: Bryan: “I never made a calculation.” Darrow: “What do you think?” Bryan: “I don’t think about things I don’t think about.” The prosecution won in court, but Bryan’s name was forever dishonored.

In Rhea County, though, Bryan is still revered. His statue on the courthouse lawn is inscribed with the words “Truth and Eloquence.” And the town is home to Bryan College, a Christian-based liberal-arts school founded in 1930 to honor the Great Commoner’s crusades at the Dayton trial. It has a total enrollment of 1,500 and a curriculum built around the inerrancy of Scripture. Bryan College found itself in the spotlight in 2014 when its board of trustees required professors to sign a statement of belief saying Adam and Eve were “historical persons created by God in a special formative act, and not from previously existing life-forms.” Two tenured professors were fired after they failed to do so.

Some members of the campus community protested: The faculty voted no-confidence in President Stephen Livesay’s leadership, 30-2; the student government association ran an open letter to the board in the Bryan Triangle; a social media campaign publicized the disapproval. A typical tweet: “I came to Bryan to expand my educational options, not limit them.”

Still, many Daytonians maintain that the Earth came into existence over the course of six days around 10,000 years ago. When asked whether he believes in evolution, Beard, the barber, responds with a sharp wince and a look indicating something between disapproval and pity. “I ain’t the kin of no monkey,” he says with heavy finality.

Monkeys have long been a sensitive subject in this town: During the trial, one of the hundreds of journalists encamped in houses and hotels was the Baltimore Evening Sun columnist H.L. Mencken, one of the most distinctive and vituperative American prose stylists of the 20th century. As he observed the frenzied gathering—the narrow streets jammed with Bible salesmen, souvenir hucksters, freak shows, a toy-piano-playing chimp named Joe Mendi, and ministers who preached about the evils of coffee, ice cream and Coca-Cola (“a levantine and hell-sent narcotic”)—Mencken called the proceedings a “universal joke”; Bryan, a “charlatan, a mountebank, a zany”; and the townsfolk, “gaping primates” and “rustic ignoramuses.”

“Mencken referred to Dayton as ‘Monkey Town,’” says Tom Davis, the county’s administrator of elections. “As you might guess, that was not a term of endearment.”

These days, locals often use the term more playfully: There’s a restaurant called Monkey Town Brewing Co. two blocks from the courthouse. In 2010, native daughter Rachel Held Evans titled her memoir Evolving in Monkey Town. Evans is Bryan College’s most famous graduate, as well as its most famous apostate. Raised in a conservative Christian home, she attended Rhea County Academy, a private Christian school, where she won the “Best Christian Attitude” award four years straight. While studying at Bryan, Evans says, she became increasingly uncomfortable with fundamentalist Christianity’s pat responses to complicated questions. “My teachers spoke negatively about evolution,” recalls Evans, who now embraces Darwin’s theory. “It was described as being contrary to the Christian faith. ‘You can believe the Bible or you can believe evolution,’ one of my professors said. ‘But you can’t believe both.’”

Those professors were not alone: A 2014 Gallup poll showed that 42 percent of Americans reject evolution. The figure hasn’t changed much over the three decades in which the survey has been conducted. Perhaps more surprising: In 2007, Penn State researchers canvassed 939 high-school biology teachers across the country and found that 16 percent said they personally believed God created human beings in the last 10,000 years.

Courts routinely overturn statutes that require science teachers to place equal emphasis on evolution and creation events. But just as routinely, anti-evolution activists introduce new variations. Louisiana skirted federal law with a 2008 act that allows teachers to use “supplemental textbooks and other instructional materials to help students understand, analyze, critique, and review scientific theories in an objective manner.” The legislation singled out theories on evolution, human cloning and climate change. Tennessee schools are not allowed to teach creationism or intelligent design, but they can present the “scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses” of theories that can “cause controversy.”

Dayton is home to the Core Academy of Science, a local ministry that offers online courses in biology, chemistry and earth science. Its president, Todd Charles Wood, came to Dayton in 2000 to preside over the now-defunct Center for Origins Research at Bryan College. Before a 2015 performance of Front Page News, Wood delivered a lecture called “The Ironic History of Evolution in the Scopes Era.” “I will not be baited into a debate by proxy with Rachel Held Evans or any other promoter of evolution,” he said afterward. “If they don’t like what I’m doing, that’s their problem. I have to answer to God for what I’m doing, not for what they’re doing. If Rachel thinks she can face Christ’s coming judgment with confidence and a clear conscience, good for her. Who am I to judge another servant?”

Evans, who still lives in Dayton, says locals continue to be profoundly shaped by the events of 90 years ago. “The characters in the Scopes Trial drama were in many ways overdrawn, even without added theatrical flourish,” says Evans. “And I often wonder if that forever changed how we view the tension between science and faith. If science is represented by the aggressively atheist Darrow and the disdainful cynic Mencken, and if faith is represented by the thundering yet unprepared Bryan, no wonder we have trouble dialoguing with one another. It’s as if we have been fighting caricatures of one another ever since 1925.”

Related Reads

Inherit the Wind