The Deadly Donora Smog of 1948 Spurred Environmental Protection—But Have We Forgotten the Lesson?

Steel and zinc industries provided Donora residents with work, but also robbed them of their health, and for some, their lives

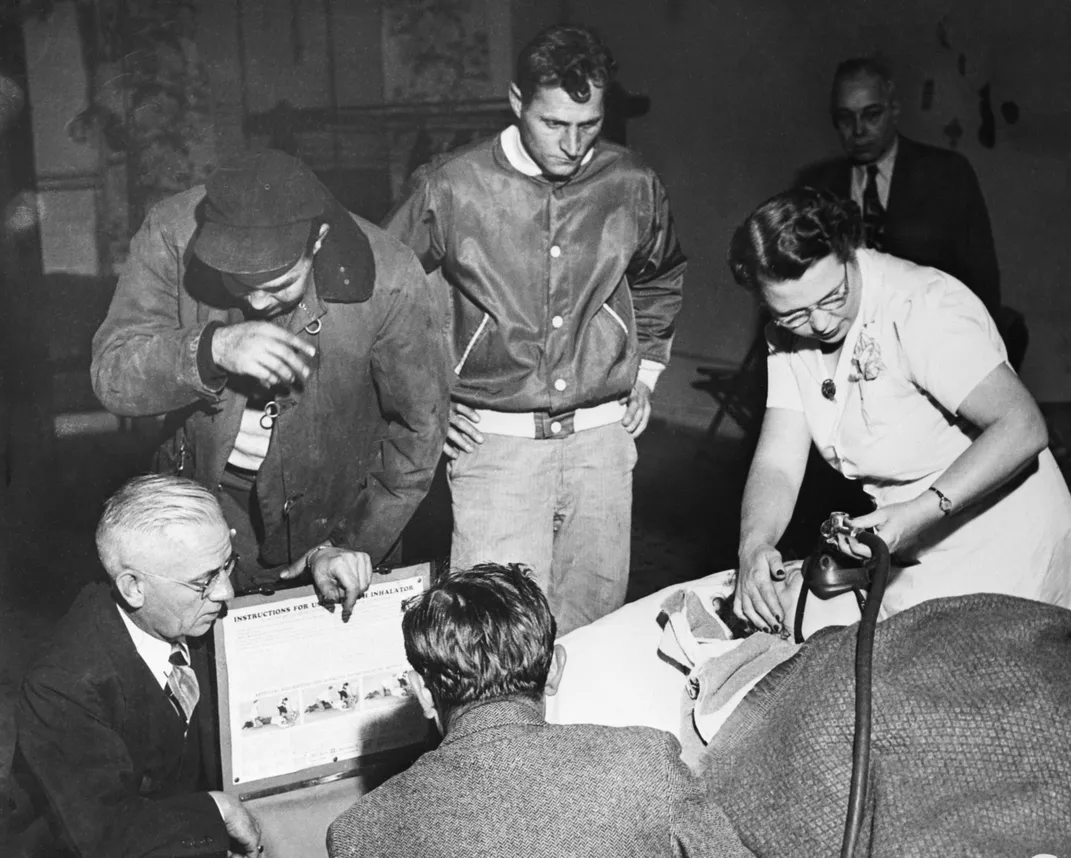

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/02/390290b4-5226-4848-af47-160cbcbbb9af/gettyimages-515485484.jpg)

The yellow fog arrived five days before Halloween in 1948, swaddling the Pennsylvania city of Donora and the nearby village of Webster in a nearly impenetrable haze. Citizens attending the Donora Halloween parade squinted into the streets at the ghostlike figures rendered nearly invisible by the smoke. The Donora Dragons played their habitual Friday night football game, but, their vision obscured by the fog, ran the ball rather than throwing it. And when terrified residents began calling doctors and hospitals to report difficulty breathing, Dr. William Rongaus carried a lantern and led the ambulance by foot through the unnavigable streets.

On Saturday October 30, around 2 a.m., the first death occurred. Within days, 19 more people from Donora and Webster were dead. The funeral homes ran out of caskets; florists ran out of flowers. Hundreds flooded the hospitals, gasping for air, while hundreds more with respiratory or cardiac conditions were advised to evacuate the city. It wasn’t until the rain arrived at midday on Sunday that the fog finally dissipated. If not for the fog lifting when it did, Rongaus believed, “The casualty list would have been 1,000 instead of 20.”

The 1948 Donora smog was the worst air pollution disaster in U.S. history. It jumpstarted the fields of environmental and public health, drew attention to the need for industrial regulation, and launched a national conversation about the effects of pollution. But in doing so, it pitted industry against the health of humans and their environment. That battle has continued throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, with short-term economic interests often trumping long-term consequences. Donora taught Americans a powerful lesson about the unpredictable price of industrial processes. The question now is whether the lesson stuck.

***

Before Carnegie Steel made its way to Donora, the town was a small farming community. Located on the Monongahela River some 30 miles south of Pittsburgh, Donora sits nestled in a narrow valley, with cliff walls rising over 400 feet on either side. Webster, meanwhile, is situated nearby, across the Monongahela. By 1902, Carnegie Steel had installed a facility in the immediate region, complete with more than a dozen furnaces; by 1908, Donora had the largest volume of railroad freight traffic in the region; by 1915, the Zinc Works began production; and by 1918 the American Steel & Wire Company paid off its first fine for air pollution damage to health.

“Beginning in the early 1920s, Webster landowners, tenants, and farmers sued for damages attributed to smelter effluent—the loss of crops, fruit orchards, livestock, and topsoil, and the destruction of fences and houses,” writes historian Lynne Page Snyder. “At the height of the Great Depression, dozens of Webster families joined together in legal action against the Zinc Works, claiming air pollution damage to their health.” But U.S. Steel rebuffed them with lengthy legal proceedings, and plans to upgrade the Zinc Works’ furnaces to produce less smoke were set aside in September 1948 as being economically unfeasible.

Despite residents’ concern about the smoke burping out of the factories and into the valley, many couldn’t afford to be too worried—the vast majority of those 14,000 residents were employed by the very same mills. So when the deadly smog incident occurred, mill bosses and employees scrambled to find another culprit for the accident (though the Zinc Works was shut down for a week as a concession).

“The first investigators were run out of town by people with handguns,” says Devra Davis, the founder of Environmental Health Trust and the author of When Smoke Ran Like Water. “The majority of the town council worked in the mill, and some of them had executive jobs, like supervisors. Any suggestion that there could be some problem with the mill itself, which was supporting them financially, was simply something that there was no economic incentive to even entertain.”

Whatever their affiliation, everyone from the town leaders to factory owners agreed that they needed answers and a way to prevent such a catastrophe from ever occurring again. In the weeks after the fog, Donora’s Borough Council, the United Steelworkers, American Steel & Wire and even the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania called upon the federal government to launch an investigation led by the nascent United States Public Health Service.

“For decades, pollution was created by very powerful industries, and the state investigations were very friendly to industry,” says Leif Fredrickson, a historian at the University of Virginia and a member of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative. “So [the people of Donora] were rightly concerned about that and wanted the federal government to get involved. But as it turns out, the Public Health Service was pretty concerned about their relationship with state researchers, and this is before the federal government has much say over what happens in terms of pollution control in state and local areas.”

The federal agency sent 25 investigators to Donora and Webster, where they took health surveys from residents, inspected crops and livestock, measured different sources of air pollution, and monitored wind speed and meteorological conditions. They found that more than 5,000 of the 14,000 locals had experienced symptoms ranging from moderate to severe, and that the American Steel & Wire Plant and the Donora Zinc Works emitted a combination of poisonous gases, heavy metals and fine particulate matter.

“If you looked at the X-rays of their lungs, they looked like the survivors of poison gas warfare,” Davis says.

A preliminary report was released in October 1949, with inconclusive results. Rather than singling out the mills and the effluent they produced, the researchers pointed to a combination of factors: the mills’ pollution, yes, but also a temperature inversion that trapped the smog in the valley for days (a weather event in which a layer of cold air is trapped in a bubble by a layer of warm air above it), plus other sources of pollution, like riverboat traffic and the use of coal heaters in homes.

Some locals pointed out the fact that other towns had experienced the same weather event, but without the high casualty. “There is something in the Zinc Works causing these deaths,” wrote resident Lois Bainbridge to Pennsylvania governor James Duff. “I would not want men to lose their jobs, but your life is more precious than your job.”

Others, furious with the outcome of the investigation and the lack of accountability for the mills, filed lawsuits against the American Steel & Wire Company. “In response, American Steel & Wire asserted its initial explanation: the smog was an Act of God,” Snyder writes.

In the end, American Steel & Wire settled without accepting blame for the incident. Although no further research was done into the incident in the years immediately after it, a 1961 study found the rate of death from cancer and cardiovascular disease in Donora from 1948 to 1957 was significantly elevated. Davis believes that, in the months and years after the incident, there were likely thousands more deaths than the ones officially attributed to the fog incident. That’s thanks to the ways our bodies respond to fine particulate matter, which were so prevalent at the time of the killer smog. The tiny particles slip into the bloodstream, causing increased viscosity. That sticky blood in turn increases the chance of a heart attack or stroke.

But, Davis says, the incident had some positive outcomes: it also sparked an interest in a new kind of public health research. “Prior to Donora there wasn’t a general appreciation of the fact that chronic exposures over long periods of time affected health. Public health back then consisted of investigating epidemics, when cholera could kill you, or polio could kill you.” Residents of Donora took pride in alerting the nation to the dangers of air pollution, Davis says (herself a native of Donora), and continue to commemorate the incident at the Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum.

Following the deadly smog, President Truman convened the first national air pollution conference in 1950. Congress didn’t pass its first Clean Air Act until 1963, but progress continued steadily after that, with President Nixon creating the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the same year that Congress passed a more comprehensive Clean Air Act. But the work of protecting the environment is never entirely finished, as new industries and technologies take the place of previous ones.

“People are still dying in the United States from pollution, and it tends to be individuals who do not have access to better housing and things like that,” says Elizabeth Jacobs, a professor of public health who wrote about Donora in the American Journal of Public Health. “But it’s not as acute now. It’s more of a long-term, chronic exposure.”

That message was echoed by medical doctors writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, who cited new studies proving the danger of fine particulate matter, no matter how small the quantity in the atmosphere. “Despite compelling data, the Trump administration is moving headlong in the opposite direction,” the authors write. “The increased air pollution that would result from loosening current restrictions would have devastating effects on public health.”

Since 2017, when that review was published, the Trump administration has relaxed enforcement on factory emissions, loosened regulations on how much coal plants can emit, and discontinued the EPA’s Particulate Matter Review panel, which helps set the level of particulate matter considered safe to breathe.

For Fredrickson, all of these are ominous signs. He notes that while the Clean Air Act hasn’t been dismantled, it also hasn’t been modified to keep up with new and more numerous sources of pollution. “At the time that things like Donora happened, there was a very bipartisan approach to pollution and environmental problems,” Fredrickson says. Regulations were put in place, and industries quickly learned that those regulations would actually be enforced. But those enforcements are falling away, it might not take long for them adjust to a new status quo of breaking rules without facing any consequences. And that, he said, “can really lead to some sort of environmental or public health disaster.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)