Many African Americans were eager to serve in the U.S. military during World War II, hoping their patriotism and courage would prove them worthy of the nation’s promise of equity for all people. But even as they battled foreign enemies that threatened our democracy, at home these men and women found themselves fighting the same racism and segregation they had endured as civilians.

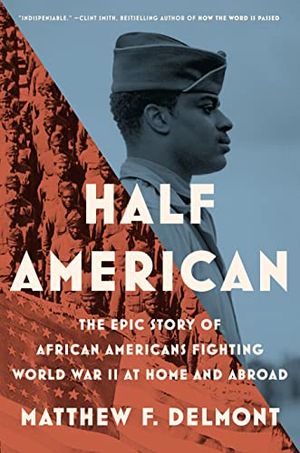

In a new book, Half American, Matthew F. Delmont, a historian at Dartmouth College, chronicles the service members’ struggles—including a momentous but largely forgotten Navy catastrophe that, he says, “helped force the Navy and the larger military to desegregate.”

At the U.S. Navy ammunition depot at Port Chicago, on Suisun Bay some 36 miles northeast of San Francisco, Black seamen worked in shifts around the clock loading ships bound for the Pacific. Every day they transferred hundreds of tons of bombs and shells from railroad boxcars to the ships. Sometimes the bombs were wedged so snugly in the boxcars that the sailors struggled to loosen them safely. It was dangerous work, and shortly after 10 p.m. on July 17, 1944, it proved deadly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/f5/29f533d3-a1b7-47f5-aa6f-74fac88314e4/sep2022_h03_halfamerican.jpg)

Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad

The definitive history of World War II from the African American perspective, written by civil rights expert and Dartmouth history professor Matthew Delmont

People throughout the Bay Area awoke to something that felt like an earthquake—a blast with the force of five kilotons of TNT. Sailors sleeping in their barracks a mile and a half from the port thought they were under attack from Japanese bombers. “Everybody felt at that point that it was another Pearl Harbor,” said Jack Crittenden, a 19-year-old seaman from Montgomery, Alabama. “People running and hollering....Finally, they got the emergency light together. Then some guys came by in a truck, and we went down to the dock, but when we got there, we didn’t see no dock, no ship, no nothing.”

One ship, the Quinault Victory, was lifted out of the water, spun around and shattered into pieces. Only tiny fragments of another ship, the E. A. Bryan, were ever recovered. All the people on the pier, aboard the two naval ships, and on a nearby Coast Guard fire barge were killed instantly. Three hundred and twenty people died, including 202 Black enlisted sailors. Only 51 bodies were recovered. It was the worst home-front disaster of the war.

Sailors raced to help injured crewmates and fought fires that could have triggered additional explosions. All of them were shaken by what they witnessed. “I was there the next morning,” Crittenden recalled in an interview with historian Robert Allen. “Man, it was awful....You’d see a shoe with a foot in it....You’d see a head floating across the water—just the head or an arm...just awful....That thing kept you from sleeping at night.” One of the seamen had been home in San Diego on leave after his wife gave birth to their son. When he returned to Port Chicago after the explosion and found all of his buddies had been killed, he said, “something just snapped” within him.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c8/2e/c82e53f4-020a-4700-8324-f2ededcc5b9c/sep2022_h08_halfamerican.jpg)

The Black sailors at Port Chicago had voiced their safety concerns numerous times over the prior year. Segregation relegated them to the dangerous task of handling tons of high explosives every day, even though the men were given no specific training. Men learned how to operate winches to move thousand-pound bombs by watching other sailors operate the machines. White officers pitted different divisions against each other, pushing the sailors to race to load the most tonnage during their shifts. Winners got access to recreational privileges, radios and Black newspapers, but as the pace ratcheted up so did the risk of an accident.

Like other Black servicemen assigned to heavy, backbreaking labor—whether in the cold of Alaska or the heat of New Guinea—the Black sailors at Port Chicago also chafed at working in segregated units under the supervision of white officers. They described themselves as a “chain gang,” “mule team” and “slave outfit,” and understood that they were cheap labor compared to civilian stevedores, who loaded and unloaded cargo from ships. A year before the explosion, a group of the sailors had written to a local attorney warning that morale had dropped to “an alarming depth” and asked for help. “We, the Negro sailors of the Naval Enlisted Barracks of Port Chicago, California, are waiting for a new deal,” they said in conclusion. “Will we wait in vain?”

Four days after the explosion that destroyed Port Chicago, the Navy began its investigation. Three senior officers and a judge advocate interviewed 125 witnesses over a month, only five of whom were Black sailors. The officers deflected blame for prioritizing output over safety and for the seamen’s lack of training. Instead, they pointed their fingers at the enlisted men. “The consensus of opinion of the witnesses...is that the colored enlisted personnel are neither temperamentally or intellectually capable of handling high explosives,” the judge advocate concluded. “It is an admitted fact, supported by the testimony of the witnesses, that there was rough and careless handling of the explosives being loaded aboard ships at Port Chicago.”

Much in the same way military leaders had blamed Black troops for the violence they encountered at Army camps in the South, now the Navy blamed Black sailors for the port’s shoddy safety protocols. Of course, the sailors who were on the Port Chicago dock that July night were not alive to defend themselves from these accusations.

Most of the surviving Black sailors were eventually transferred to the naval barracks in Vallejo, California, near the Mare Island shipyard and ammunition depot. They were in shock and still mourning the deaths of so many of their friends. Men startled at every slammed door and dropped box. Without any information about what caused the explosion, they were anxious about returning to ship-loading duty. They already resented their day-to-day treatment as laborers, and now they worried that every bomb they moved could be their last. To make matters worse, the Navy gave white officers 30-day survivor’s leave to visit their families before returning to regular duty but denied Black sailors the same benefit.

As the men worked at the barracks in Vallejo and it became clear they would soon resume duty under the same officers, they began to talk among themselves about refusing to load ammunition. In early August, when the officers tried to march the Black sailors to the Mare Island ammunition depot, the majority refused to go. The men were told they would face severe penalties if they did not return to work, but the protests persisted. By the end of the afternoon, more than 250 Black sailors were imprisoned on a barge, where they were guarded by Marines and held for three days.

Joseph Small, a sturdily built seaman first class, emerged as a protest leader. The younger sailors respected the 22-year-old Small like an older brother. As tempers flared on the cramped ship, Small urged the men to stick together, remain composed and avoid getting in trouble with the guards. In the chow hall, he organized the men to cook, serve meals and clean the kitchen. “We’ve got the officers by the balls—they can do nothing to us if we don’t do anything to them,” he told the men. “If we stick together, they can’t do anything to us.”

Small and others were optimistic that if they demonstrated they were not refusing to work, only to load ammunition, they would be transferred to other duty. The men did not anticipate that what they saw as a work stoppage—akin to a wildcat strike—the Navy saw as mutiny. “As far as we were concerned mutiny could only be committed on the high seas,” Small recalled. “We didn’t try to take over anything. We didn’t try to take command of the base. We didn’t replace any officers; we didn’t try to assume an officer’s position. How could they call it mutiny?” The sailors would pay dearly for this faulty assumption.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/18/a8/18a85059-0a44-4050-abfd-5e9d6abe2a9c/sep2022_h01_halfamerican.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e6/c9/e6c9d14a-7361-406e-be25-231bf547a16e/sep2022_h02_halfamerican.jpg)

When the men were released from the ship, they were marched to a baseball field under armed guard. Adm. Carleton Wright, commander of the 12th Naval District headquartered at Mare Island, arrived in a jeep and proceeded to berate and threaten the Black sailors. “I want to remind you that mutinous conduct in the time of war carries a death sentence,” Wright said, “and the hazards of facing a firing squad are far greater than the hazards of handling ammunition.” Men not long removed from civilian life, who less than a month earlier had seen hundreds of their friends and fellow sailors blown up, were now being told they could be executed if they did not load explosives. When the admiral left, the officers ordered the men to go to one side if they would follow orders to load ammunition and to the other side if they refused.

It was a wrenching decision, and men wept openly as they tried to balance their own lives against their bonds with other Black sailors. More than 200 men decided to return to work, and the admiral recommended they be charged with summary courts-martial for refusing to obey orders. When the Navy notified President Franklin Roosevelt of the decision, he wrote, “It seems to me we should remember in the summary courts-martial of these 208 men that they were activated by mass fear and that this was understandable. Their punishment should be nominal.” The other 50 men, who refused to load ammunition, were charged with conspiring to make a mutiny; they were transferred 30 miles south to the brig at Camp Shoemaker, and interrogated. The charges the men faced carried lengthy prison sentences, and possibly death.

The trial began on September 14 before a seven-member court of senior naval officers appointed by Admiral Wright. They served as both judge and jury. Lt. Cmdr. James F. Coakley led the prosecution. Lt. Gerald Veltmann, a 33-year-old Houston lawyer, headed the defense, and the Judge Advocate’s office assigned five lawyers to represent groups of ten men. All of the officers trying and deciding the case were white. In the courtroom the senior naval officers were seated directly across from the prosecution and defense, while the Black sailors lined the periphery, listening anxiously while their lives hung in the balance.

The court-martial of the Port Chicago seamen was the first U.S. mutiny trial of World War II and the largest mass trial in Navy history. Unusual for military trials, the Navy encouraged newspaper and wire-service reporters to cover the proceedings, intending the national publicity to show that the Black sailors were receiving a fair trial while also serving as a warning to other troops who might be tempted to disobey orders.

The prosecution argued that the sailors’ fear was no excuse for their insubordination and that the meetings Joseph Small organized aboard the barge constituted a conspiracy to mutiny. The defense countered that the officers asked the sailors if they were willing to load ammunition after the explosion, but had not ordered them to do so. The men refused to move explosives because they were fearful, the defense contended, not conspiring to mutiny. “Those men were no more guilty of mutiny than they were of flying to the moon,” Veltmann argued.

The families of the 50 men contacted the NAACP, and Thurgood Marshall, then the director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, flew to San Francisco in October to attend the trial and contribute to the sailors’ defense. “This is not an individual case,” Marshall argued. “This is not 50 men on trial for mutiny. This is the Navy on trial for its whole vicious policy toward Negroes.” Marshall demanded a formal government investigation of Port Chicago, including why Black seamen were assigned to segregated labor units and why they were given no safety training before being required to move dangerous explosives. “I want to know why the Navy disregarded official warnings by the San Francisco waterfront unions—before the Port Chicago disaster—that an explosion was inevitable if they persisted in using untrained seamen in the loading of ammunition,” Marshall said. “I want to know why the Navy disregarded an offer by these same unions to send experienced men to train Navy personnel in the safe handling of explosives....I want to know why the commissioned officers at Port Chicago were allowed to race their men. I want to know why bets ranging from five dollars up were made between division officers as to whose crew would load more ammunition.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f0/4c/f04caf88-e420-4dfe-8cd4-4cc56d252b9d/sep2022_h05_halfamerican.jpg)

After six weeks of hearings, the jury of senior naval officers adjourned to make their ruling. Their deliberations barely extended over the lunch hour before they reached a verdict: They found all 50 Black sailors guilty of mutiny. The men were sentenced to between five and 15 years in prison. Marshall wryly noted that the officers deliberated for about a minute and a half for each defendant. He immediately started working on the appeal process, which carried into the following year.

The NAACP published Mutiny?, a pamphlet ghostwritten by Mary Lindsey, a white reporter for the leftist People’s World newspaper, to call attention to the case and urge members to write protest letters to the Navy. “The Navy has a slogan—‘Remember Pearl Harbor’—a reminder of foreign treachery against democracy,” the pamphlet concluded. “There is another slogan the Navy should adopt. It is a reminder of what treachery to our own ideals within a democracy does to that democracy. The pointless, meaningless deaths of over 320 Americans must be given a point, must be given a meaning—for the living. Remember Port Chicago!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e2/00/e2003097-d3d7-4631-b6b2-155e5eb9994b/sep2022_h09_halfamerican.jpg)

Marshall took the appeal to the Navy’s Judge Advocate General’s office in Washington, D.C. He argued that the military was too quick to label any disobedience by Black sailors or soldiers as a mutiny and that the Navy was making scapegoats of the men to cover up the practices that led to the explosion. Marshall’s appeal was unsuccessful, and the Black sailors spent the rest of the war in the Terminal Island military prison in San Pedro, south of Los Angeles. Amid growing pressure to desegregate the military, the Navy eventually shortened the sentences and released the men from prison in 1946. Efforts to clear the sailors’ names would continue for decades after the war.

Port Chicago was just one of several cases of Black military personnel protesting discriminatory treatment. The 12,500 Black Seabees (Naval Construction Battalion personnel) did important work for the Navy. They built advanced bases, constructed underwater slips for naval vessels, and off-loaded cargo. Like other Black military laborers, they worked under white officers. A thousand Black Seabees, who had served nearly two years overseas in Tulagi and Guadalcanal in the Pacific theater, staged a hunger strike at Camp Rousseau in Port Hueneme, California, after their commanding officer refused to promote Black Americans and assigned Black Seabees only to unskilled manual labor. “It is discouraging and destructive to the morale when they see white men with much less preparation than they have, and with no more apparent qualifications of leadership than they possess, being advanced beyond them,” NAACP acting secretary Roy Wilkins said. Nineteen of the Seabees were discharged for seditious behavior.

At Freeman Army Airfield, in Indiana, more than 100 Tuskegee Airmen officers were arrested when they attempted to integrate an all-white officers’ club. “I’d flown 67 combat missions in Europe,” Lt. Col. Clarence Jamison recalled. “As an officer of the United States Army Air Corps, who’d put his life on the line for this country, why couldn’t I use a United States Army officers’ club?” The Black pilots had endured racism at Tuskegee, from segregated bathrooms on base to violence at the hands of police in town. They had risked their lives and lost friends fighting for a country that treated them as less valuable than white citizens. Now they were fed up. Their protest happened to take place at an officers’ club, but it was about much more than that. “It was a slap in the face,” Jamison said. “It defiled the graves of [Black pilots]...who’d made the ultimate sacrifice for their country but couldn’t get into a dive club because of their skin color.”

At Fort Devens in Massachusetts, 51 Black women went on strike to protest racial discrimination in the Women’s Army Corps. Many of the women were college graduates and were enticed to enlist in the WAC by promises of skilled jobs, only to be assigned cleaning duty. Alice Young, a 23-year-old from Washington, D.C., who left nursing school to join the WAC, recalled that her hospital commander told her, “I do not have colored WACs as medical technicians. They are here to scrub and wash floors, wash dishes and do all the dirty work.” The four strike leaders—Mary Green, Anna Morrison, Johnnie Murphy, and Young—were court-martialed. “If it will help my people by me taking a court-martial, I would be willing to take it,” Morrison said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/23/f6/23f60529-66a9-462a-aea2-170c890af701/sep2022_h06_halfamerican.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/12/67/1267db57-31a5-4cbb-80e7-320e48e1cd22/sep2022_h07_halfamerican.jpg)

Hundreds of other Black soldiers and sailors staged their own individual protests, refusing to obey racially unjust orders from officers, military police or local sheriffs. Second Lt. Jackie Robinson was court-martialed at Camp Hood, in Texas, in the summer of 1944 when he refused to move to a seat in the back of an Army bus. Robinson was with the light-skinned wife of another Black officer, and the two had picked seats in the middle of the bus. “The driver glanced into his rear-view mirror and saw what he thought was a white woman talking with a black second lieutenant,” Robinson remembered. “He became visibly upset, stopped the bus, and came back to order me to move to the rear. I didn’t even stop talking, didn’t even look at him....I had no intention of being intimidated into moving to the back of the bus.”

Although Robinson was three years away from breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball, he was already a well-known athlete after starring in four sports at UCLA. Word of his court-martial would likely garner national attention, so after the arrest, Robinson wrote to Truman Gibson, who was chief civilian adviser to the Secretary of War. Robinson asked his advice. “I don’t want any unfavorable publicity for myself or the Army, but I believe in fair play, and I feel I have to let someone in on the case,” he wrote. “I don’t care what the outcome of the trial is because I know I am being framed and the charges aren’t too bad.” The court-martial trial moved quickly, and the Army acquitted Robinson, granting his request for exemption from active military service, and honorably discharged him in the fall. The unit Robinson was attached to, the 761st Tank Battalion, nicknamed the “Black Panthers,” went on to distinguish itself in the Battle of the Bulge as part of Gen. George Patton’s Third Army.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/09/2909120b-69d6-4134-84d5-45d0224fc6cf/sep2022_h04_halfamerican.jpg)

“Why do Negro soldiers and sailors mutiny?” the Chicago Defender asked, after 73 soldiers in the 1320th Engineer General Service Regiment in Hawaii were court-martialed and convicted of mutiny. The men worked in a labor battalion, clearing airfields and moving tons of earth. They refused to show up for work after their Black officers were transferred. The Chicago Defender argued that the men’s defiance was deeply rooted in histories and traditions of Black resistance. “From slavery to slave labor has been the fate of the Negro who becomes a soldier or sailor. As a slave, the Negro revolted—fought, bled and died to break the chains that bound him. As slave labor in the Army and Navy, he is doing no less.”

Marshall and the NAACP were involved in almost all these court-martial and mutiny cases and saw a clear pattern. “It is apparent that most of these incidents arose from a final break in the spirit of the Negro soldiers due to continued mistreatment,” he said. “The tendency in ‘military circles’ seems to be that any concerted display of resentment against ill-treatment among Negro soldiers is called ‘mutiny.’” The common thread that connected the Black sailors at Port Chicago, Seabees at Camp Rousseau, Tuskegee Airmen at Freeman Field, WACs at Fort Devens, and thousands of other troops was their desire to serve their country without being discriminated against or degraded. As the Chicago Defender put it: “The Negro will give life for his country—but he will not be a slave.”

From Half American by Matthew F. Delmont, to be published on October 18, 2022, by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (C) 2002 by Matthew F. Delmont

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1260x1674:1261x1675)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e8/81/e8814394-3d27-4317-9e6a-66f894ae7212/sep2022_h11_halfamerican.jpg)