The Debate Over Rebuilding That Ensued When a Beloved French Cathedral Was Shelled During WWI

After the Notre-Dame de Reims sustained heavy damage, it took years for the country to decide how to repair the destruction

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/e3/f7e315b9-165a-4a41-a46b-6380b50d9a83/shell_explosion_cathedral_at_rheims.jpg)

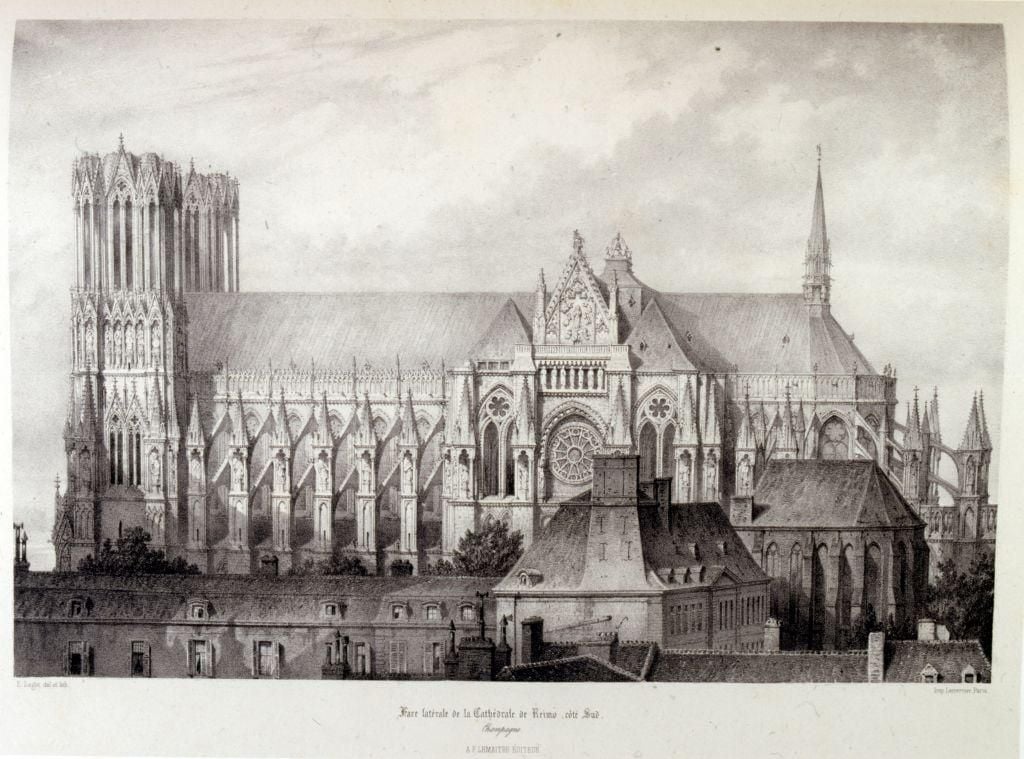

For nearly a millennium, the French city of Reims was synonymous with its towering Gothic cathedral known as Notre-Dame. Not to be confused with the cathedral sharing the same name in Paris, the Reims church was the heart and soul of the region, its tallest towers rising 265 feet above the city’s 50,000 residents, its resplendent halls used for the coronation of nearly every monarch since the 13th century. But on the eve of the First World War in 1914, the cathedral’s magnificence brought it a different kind of attention: that of an easy target.

When the fighting began in August of that year, the invading German army quickly overwhelmed the northeast part of France, including Reims, and transformed the cathedral into an infirmary. They filled the church with 3,000 cots and 15,000 bales of dried grass to use as pallets—all of which remained inside the building after September 4, when the Allied forces of France and the United Kingdom sent the Germans on a rapid retreat after the First Battle of the Marne. With Reims now only a handful of miles from the front, the real destruction began.

Five German artillery shells hit the cathedral on September 18, crashing into the medieval structure, but the more devastating attack came a day later. “The projectiles, perhaps incendiary, set afire first the scaffold [around the towers] and then the hay. No more inflammable tinder could have been devised, and no accelerant was required,” writes historian Jan Ziolkowski. Lead from the burning roof poured through the mouths of the church’s stone gargoyles; windows exploded; the Smiling Angel statue that had stood near the front door for centuries lost its head.

Unlike the recent fire at Notre Dame de Paris, the assault on Reims Cathedral continued for four years. Around 300 German shells smashed into Notre Dame de Reims after its initial fire; around 85 percent of buildings in the city were destroyed as well. By the end of the war, the famous cathedral was a skeleton of its former self, and a symbol of the incomprehensible brutality of the conflict.

* * *

From its earliest days, the city of Reims (pronounced rahnce) was a cultural crossroads. As one of the Roman Empire’s largest cities, it hosted merchants from across the continent, and in 496 it also became the center of French Christendom. According to an account written long after the fact, that year marked the baptism of King Clovis. The Frankish leader had already united the surrounding territories into what would become France; now he was transforming the region’s religious landscape. It seemed only fitting that some 700 years later, a massive cathedral would be built on the same spot.

The question of when construction began on Notre Dame de Reims has been debated for decades. “There’s this document that talks about a fire and gives a date of 1210,” says Rebecca Smith, an art historian at Wake Tech Community College who has written extensively about the cathedral’s origins. “They don’t mention what burns or how much damage there is, but everybody assumed the cathedral must’ve started construction around 1211 right after the fire.”

But recent archaeological analysis by researchers Willy Tegel and Olivier Brun has shown otherwise. They used recovered wood fragments dating all the way back to around 1207 to prove the cathedral was under construction earlier than believed.

What no one doubts is the importance of the cathedral from its start. The beginning of the 13th century marked a dramatic increase in the number of Gothic cathedrals being erected. The architectural style was a flamboyant one, with religious buildings adorned by flying buttresses and elaborate decorations. The goal for these churches, Smith says, was “to show off the stained glass, to be taller and thinner and push toward the heavens, toward God.” And since the cathedral at Reims was being erected around the same time as Notre Dame de Paris, an element of competition arose between the cities.

But Reims Cathedral secured its place in the religious hierarchy early in its 75-year construction. When a 12-year-old Louis IX was crowned in 1226, he declared that all future monarchs would be coronated at Notre Dame de Reims, harkening back to the history of Clovis as France’s first Christian king. This decree was largely followed for the next 500 years, including a famous episode in 1429 when Joan of Arc fought past opposing forces to bring the French prince to Reims where he could be legitimately crowned Charles VII.

The cathedral also survived multiple calamities. In 1481, a fire burned through the roof, and a storm on Easter Sunday in 1580 destroyed one of the great windows. The church even survived the French Revolution of 1789, when the monarchy was temporarily overthrown. The coronation cathedral remained intact despite fighting across the country; citizens recognized its historical importance and couldn’t bear to see it ravaged.

These centuries of attachment to the cathedral made its destruction in World War I that much more devastating. Upon returning to Reims after the fighting, French author Georges Bataille wrote, “I had hoped, despite her wounds, to see in the cathedral once again a reflection of past glories and rejoicing. Now the cathedral was as majestic in her chipped and scorched lace of stone, but with closed doors and shattered bells she had ceased to give life… And I thought that corpses themselves did not mirror death more than did a shattered church as vastly empty in its magnificence as Notre-Dame de Reims.”

When France passed a law supporting the reconstruction of damaged monuments at the end of the war in 1919, fierce debates erupted over what work should be done on Reims Cathedral. Many argued in favor of leaving it as a ruin. “The mutilated cathedral should be left in the condition in which we have found it at the end of the war,” argued architect Auguste Perret. “One must not erase the traces of the war, or its memory will be extinguished too soon.” According to historian Thomas Gaehtgens, Perret even argued for building a concrete roof over the crumbling cathedral so that all could see the destruction the German army had wrought.

But Paul Léon, director of historic preservation at the Ministry of Culture, thought differently. “Does anyone really believe that the inhabitants of Reims could bear the sight of the mutilated cathedral in the heart of their city?” Besides that, the cold and wet climate of Reims would make it exceedingly hard to preserve the ruins.

After months of debate and assessments of the damage, reconstruction finally began in late 1919. The Reims Cathedral became a global cause célèbre, and donations poured in from countries around the world. Among the most sizeable donations were several from oil baron John D. Rockefeller, who gave more than $2.5 million (almost $36 million in today’s dollars) to be put towards the reconstruction of several French monuments. By 1927 a large portion of the work was complete, though restoration of the facades, buttresses and windows continued until July 10, 1938, when the cathedral reopened to the public.

Much of the cathedral was restored as it had been before the war, though the chief architect overseeing reconstruction, Henri Deneux, was initially criticized for using reinforced concrete rather than wood for the roof. As for the damaged sculptures, some were left has they were, with chips still knocked out. This included gargoyles with solidified lead still dripping from their mouths. As for the famous stained-glass windows, some had been rescued over the course of the war, while many others were remade by artists who referenced other Middle Age artworks, rather than trying to create a pastiche.

Of course, the architects and artists working on reconstruction couldn’t have predicted that yet another war would soon engulf the continent. Although the cathedral again suffered some damage during World War II, it received far fewer attacks and remained largely intact.

“Cathedrals are living buildings,” says Smith, the art historian. “They’re constantly undergoing cleanings, they’re constantly undergoing restorations and renovations. They’ve always been understood as needing to flex.” For Smith, deciding how to rebuild or restore medieval architecture requires a delicate balance between preserving the past and erasing it to make way for the future. But that is something architects who worked on Notre Dame de Reims have always taken into consideration.

As for Notre-Dame de Paris, investigations are ongoing to understand what caused the devastating fire that consumed much of the cathedral’s roof. Construction workers have hurried to prevent any further collapses on the crumbling structure, but more than $1 billion has already been raised to rebuild the Parisian monument.

But it’s worth reflecting on the example of the Reims Cathedral, and the knowledge that these medieval marvels were built with an eye toward longevity. They were physical representations of humankind’s attempt to reach the divine from our lowly place on Earth. It’s a sentiment that has survived countless catastrophes—and will likely survive many more.

Editor's note, April 19, 2019: This piece has been corrected to note that Rebecca Smith did not contribute to the analysis of the early wooden fragments from the church.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)