Buffeted by hoots and catcalls, a civil rights lawyer named George Vaughn approached the lectern at the 1948 Democratic National Convention (DNC) in Philadelphia. He was one of only 17 Black delegates and alternates among nearly 1,500 white ones in the arena. As the assemblage already knew from hours of preliminary battling, Vaughn was about to call for the expulsion of a particular group of white attendees: the delegation representing the segregationist faction of the Mississippi Democratic Party.

“We … recommend that the delegation from the State of Mississippi be not seated by reason of the acts of the convention held in that state,” Vaughn said, citing resolutions adopted by the state party at its meeting three weeks earlier. These measures bound the delegates to oppose President Harry S. Truman and a civil rights plank, or declaration, in the party’s platform unless both were weighted down with the formal approval of states’ rights—the concept that Southern states were permitted to impose racial inequality regardless of federal law. If these demands were not met, the delegates would walk out of the convention.

Undeterred by the angry response from other Southern delegations, Vaughn continued, “Harry S. Truman has not advocated a single proposition in his civil rights program but what is contained in the Constitution.” So furious were the segregationists at these words that “an air [of] tension, in which physical violence lurked around a corner, hung over the great hall as [temporary convention chair Alben] Barkley pounded his heavy gavel, shouted and [pleaded] for order,” as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

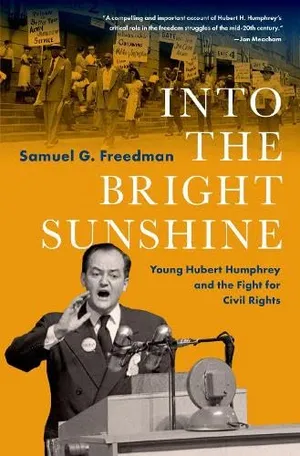

Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights

A revisionist and riveting look at the American politician whom history has judged a loser but who played a key part in the greatest social movement of the 20th century

Vaughn’s attempt to oust Mississippi’s segregationist delegates ultimately failed. But his public repudiation of the Democratic Party’s white supremacist elements foreshadowed a similar push that took place 16 years later, at the 1964 DNC. An insurgent, racially integrated slate of delegates representing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and embodied most indelibly by sharecropper-turned-activist Fannie Lou Hamer took its cause to the convention floor in Atlantic City and the television networks broadcasting nationwide. The dissidents demanded that, in keeping with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s bold progress on civil rights, the commander in chief and his loyal delegates oust the official, all-white Mississippi delegation with its defiant commitment to the Jim Crow system. Subsequent reforms forbade all-white delegations from 1972 onward.

Long overlooked by historians in favor of the 1964 convention, the 1948 episode represented a milestone in the Democratic Party’s internal struggle over civil rights during the middle of the 20th century. Inspired by Vaughn and even more so by a speech the following afternoon from the youthful mayor of Minneapolis, Hubert Humphrey, to “get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights,” Democratic delegates endorsed an unequivocal civil rights plank in the party platform for the first time ever. That stance drove the segregationist wing to bolt from the convention and form its own Dixiecrat party; it forced a reluctant Truman to run as a civil rights candidate, starting with his executive order two weeks later desegregating the American military; and it catalyzed a surge of Black voters in swing states, providing Truman a margin of victory over Thomas Dewey in the November 1948 presidential election. Seen through the long lens of history, then, the insurgency that brought Vaughn to the convention rostrum amounts to a missing link in America’s civil rights narrative.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/40/bd/40bd27fd-cd17-4a19-b74f-016585316086/61-116-23tif.jpg)

Vaughn’s path to the convention began six months earlier with two very different white men in Mississippi. One of them was Fielding Wright, a plantation country scion who was the state’s governor. The other was the Reverend Charles Granville Hamilton, an Episcopal minister in the county seat of Aberdeen and a local New Deal politician on the side. Officially speaking, both men entered 1948 as members of the Mississippi Democratic Party—the only option, really, in what was essentially a one-party state. Unofficially, they were headed for a confrontation over what shape the state party, and indeed the Democratic Party nationally, should take.

Since 1932, the New Deal coalition that powered the Democratic Party had depended on an improbable amalgamation of organized labor, urban Catholics and Jews, college-educated liberals, and an ironclad bloc of Southern white supremacists. Loosely united by an overarching commitment to a social compact and economic justice, even when both elements were not extended equally to Black Americans in the South, the alliance proved unsustainable in the years directly following World War II.

On the very day in January 1948 when Wright was inaugurated in the state capital of Jackson, he declared war on his party’s sitting president. In late 1946, Truman had appointed a Committee on Civil Rights, which recommended such measures as federal bans on poll taxes and lynching, and the creation of a permanent federal fair employment commission. Truman even addressed the NAACP in June 1947, becoming the first president to do so. And though the commander in chief tried to downplay civil rights heading into election season, hoping that he, like his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, could hold an electoral majority by means of creative ambiguity on the subject of racial equality, Wright was having none of it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5a/95/5a95f578-0047-47c7-87d7-66ca9fd37fb4/fielding_l_wright_portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/9b/5f9b7e0a-63c3-441a-a948-7c1960e9446f/states.jpg)

The Truman program, the governor thundered in his inaugural address, consisted of “elements so completely foreign to our American way of living and thinking that they will, if enacted, eventually destroy this nation and all of the freedoms which we have long cherished and maintained.” Civil rights had to be resisted—and white supremacy protected—“with all means at our hands.”

On the deliberately provocative date of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12, Wright took his nascent revolt another step forward, convening 4,000 true believers from across the South. Against a backdrop of Confederate flags and rebel yells, Wright explicitly threatened “temporarily withholding our electoral votes” from Truman. Several days later, the splinter States Rights’ Democratic Party set up shop in a Jackson hotel. Its members subsequently resolved that no Democratic delegate from 12 Southern states—including the Mississippi delegation led by Wright himself—would vote to nominate a candidate for president or vice president who supported civil rights or approve a party platform endorsing civil rights legislation.

Hamilton, the Aberdeen minister, had actually attended the February gathering, futilely trying to speak in opposition to Wright. The experience of being shouted down that day merely confirmed how much of an alien the religious leader already was. As his own father-in-law put it in a cautionary letter: “I sincerely hope you have sense enough to accept this repudiation and keep out of this mess. You are a minister and a teacher, and a good one at both, and I would like to see you devote your [entire] time to both. The people of [Mississippi] don’t want you in their political life.”

Raised in the border state of Kentucky, Hamilton had attended Berea College, an institution founded by abolitionists and committed to having an interracial student body. By the mid-1930s, Hamilton was employed at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Aberdeen, which had been a hub of cotton trading during the Confederacy and the site of periodic lynchings since Reconstruction. Amid that hostile climate, Hamilton stuck out as “a rare specimen in the Deep South with reference to the Negro people,” as a Black minister once put it. He pressed his fellow Episcopal ministers to support anti-lynching legislation, worked with the National Committee to Combat Antisemitism and volunteered for the Southern Conference for Human Welfare as soon as that civil rights organization was founded in 1938.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ad/6d/ad6db299-a540-45f5-90d2-47c3003b1916/presdient_harry_s_truman_and_vice_president-elect_alben_w_barkley_in_the_washington_dc_train_station_sitting_on_-_nara_-_199937.jpg)

Far from heeding his father-in-law’s advice, Hamilton gathered sympathetic politicians from about half of Mississippi’s counties who shared his opposition to Wright’s impending break with the national party. They chose their own alternative set of delegates, who were united by a commitment less to civil rights than to Truman and the party establishment, and called themselves the Loyal Democrats. In July 1948, Hamilton traveled to Philadelphia to present the group’s case for being seated. Until they were seated, Hamilton insisted, he would not release his delegates’ names, for fear that premature exposure would cost them their jobs—and possibly their physical safety—back in Mississippi. (Based on articles that appeared months later, the likely members of his slate included labor activists from the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which was trying to undertake interracial organizing in the South, as well as several college professors.)

Precisely because Hamilton was not a recognized delegate in Philadelphia, he needed someone who was already on the Credentials Committee, which rules on contested delegation claims, to introduce the motion on his behalf. A liberal delegate, Paul Douglas, suggested that Hamilton rely on Vaughn. Though Hamilton and Vaughn had never met before, the Missourian was one of the finest Black attorneys in America, fresh off a victory in a landmark civil rights case argued before the Supreme Court.

The descendant of enslaved people and a graduate of both a historically Black college and law school, Vaughn entered political life in St. Louis in the 1920s as a Republican but shifted to the Democratic Party during the New Deal. His partisan loyalty earned him the position of Missouri’s assistant attorney general in 1941. His fame and impact, though, arose from his private law practice. He represented J.D. and Ethel Lee Shelley, a Black couple who had been denied the right to purchase a home in a St. Louis neighborhood due to its restrictive housing covenant. Vaughn argued their case through lower courts for two years, earning the sobriquet “Fighting George” from the Pittsburgh Courier, before the Supreme Court agreed to hear it in early 1948. On May 3, the justices handed down a unanimous decision declaring that state enforcement of racial covenants violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

A steadfast supporter of Truman, Vaughn was named an alternate delegate to the Philadelphia convention and rewarded with a seat on the Credentials Committee. When the committee convened on the afternoon of July 13, a series of challenges to all-white delegations from the Jim Crow South quickly emerged.

The decision in Shelley v. Kraemer was monumental in that it ended one of the most impactful forms of housing discrimination. One of the most important Equal Protection cases, Shelley would set important precedent for cases to follow like Brown v. Board of Education. #BHM pic.twitter.com/sFLZauKB5f

— Legal Defense Fund (@NAACP_LDF) February 3, 2022

One of those controversial slates, from South Carolina, included Governor Strom Thurmond, a key figure in Wright’s movement. A judge in the state had recently ordered that Black people be allowed to vote in the Democratic primary. On that basis, two different interracial slates of delegates—the Progressive Democrats and the Citizen’s Democratic Party—sought to replace the Thurmond group, which they asserted was the product of the exact sort of all-white voting that was now prohibited. But the competition for primacy between the two civil rights slates, in addition to the prospect of uprooting white delegates for Black ones, doomed the challenge. The Credentials Committee voted with only three dissenters to seat Thurmond’s segregationists.

That kind of rout, relying on votes from Northerners as well as Southerners, liberals as well as conservatives, boded ill for the Loyal Democrats from Mississippi. Still, Hamilton’s slate was presumed to be all white, making its investiture somewhat less controversial. In addition, Vaughn and Hamilton depicted the Wright delegates as the actual insurrectionists, for they had sworn to defy Truman unless he capitulated on state’s rights. Finally, the pair raised the issue of racial discrimination. Four years had passed since the Supreme Court outlawed all-white primary elections. Yet Black Americans are denied the right to register, vote or participate in government in Mississippi, Vaughn said, and on that basis, Wright’s delegates had not been democratically chosen. In response, Wright’s supporters fumed that Hamilton’s contingent was “deliberately stirring up racial hatred for political gain.”

The arguments flew back and forth as four hours elapsed, and the committee could not vote because it was short of the 27 people required for a quorum. The chair, Mary Teresa Norton of New Jersey, asked Hamilton and Vaughn if they would agree to suspend the rule requiring a quorum so a vote could immediately be held. They did. The subsequent vote ended in a tie for seating or rejecting the Loyal Democrats—a shocking blow to the segregationists. It was also a problem that Norton somehow had to solve. As she proposed that debate resume before trying a second ballot, two absent delegates, one from Alabama and the other from Mississippi, returned to the committee room. Meanwhile, two liberal members left, in either an example of terrible timing or last-minute cowardice. Norton called for another vote, and Wright’s slate was affirmed by 15 to 11.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/89/0c89eba8-17d8-4aee-a3a9-ad711bdd99a8/screenshot_2023-07-17_at_92819_am.png)

Being the kind of lawyer he was, envisioning the chessboard several moves ahead, Vaughn announced he would resume the battle before the full convention that same evening. In order to do so under convention rules, he required a formal request from ten delegates of ten different states. He had already locked up all of them.

When Norton stood at the Convention Hall rostrum soon after 9 p.m. for her designated 30 minutes of speaking time, she immediately yielded 10 of them to Vaughn to present the minority report—that is, the case for evicting Wright’s slate and installing Hamilton’s. The boos began right away, and Senator Barkley of Kentucky, as temporary chair of the convention, banged down his gavel for order. Vaughn proceeded with his prosecution, reciting the exact wording of two resolutions the Mississippi Democratic Party had adopted at its party convention three weeks earlier: “Loyal Mississippi Democrats may be absolutely certain that their delegates … will positively withdraw from that convention unless the party embody in its platform a positive plank to the effect that it will fight to uphold states’ rights.” The lawyer then called for the state’s delegation to “be not seated,” drawing a renewed round of angry shouts from the audience.

Raising his voice and lifting his arms, Vaughn proclaimed the products of Jim Crow in Mississippi: lynching, mob violence, poll taxes, underemployment, inferior education, segregated trains and buses, exclusion from the entire political process. “As long as they do not participate in its government,” he declared, “Black men could never have their rights.”

Incensed, delegates poured into the aisles as Philadelphia police strove to force them back into their seats. In the Alabama, Mississippi and Texas sections, delegates stood on their chairs and bellowed out rebel yells. One attendee made it all the way to the rostrum, posting a sign saying, “Don’t be unbrotherly, BROTHER.” A Florida delegate shouted “sit down” at Vaughn. Amid the “angry roars of disapproval and ear-shattering boos,” with the delegates’ faces purpling with rage, Barkley’s gavel was “busier than a blacksmith’s hammer at a horseshoeing,” in the piquant words of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/56/c7/56c7e0e9-7a04-4877-b252-68af7a0bd0ac/hatch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9c/16/9c16af18-4092-439c-be0f-b07151771edf/norton.jpg)

After Vaughn concluded, the police cleared the aisles, and Barkley imposed a semblance of order. Norton returned to the microphone to grant five minutes of her time to Carl A. Hatch, a New Mexico senator on the Credentials Committee. Favorably disposed toward civil rights, Hatch nonetheless had orders from party leaders to avoid a public clash on the issue at all costs. He dutifully recommended that Wright’s delegates be seated. With similar obedience, Barkley called for a voice vote rather than a roll call, first on the Credentials Committee’s majority report seating Wright’s slate and then on Vaughn’s minority report impaneling Wright’s dissidents.

Cacophony ensued.

No sooner did Barkley announce that “the ayes have it” than former Mayor of Chicago Edward Kelly ran forward from the Illinois section to demand that his delegation’s votes for the minority report be recorded. Delegates from New York and California shouted out the same order. Just as an Illinois delegate began to speak, probably to insist upon a roll call, all the floor microphones went mysteriously silent. Muted, the liberals on the convention hall beseeched Barkley by wildly waving their banners. Presumably as a way of appeasing the civil rights forces, Barkley asked every willing delegation to send a tally of its votes to the podium.

The final tally showed that 503 delegates had voted for the minority report, in favor of throwing out the states’ rights slate from Mississippi. The Democratic convention had fallen just 115 votes short of breaking Southern power. The near miss attested to the unexpected might of civil rights liberals in the convention. The very next night, in the aftermath of Humphrey’s “bright sunshine” speech, the civil rights plank carried a majority of the delegates.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ad/81/ad812bad-d560-4d34-bc96-5f1f3a9ee031/2013-3717tif.jpg)

There is no single answer as to why the righteous mutiny of Vaughn and Hamilton has all but vanished from historical memory, while the 1964 convention remains a watershed moment in the fight for civil rights. In an email to Smithsonian magazine, the historian Julian E. Zelizer, who is writing a book about the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, suggests a few elements: far more expansive television coverage in 1964 as opposed to 1948, the presence of a public speaker as riveting as Hamer was during the Atlantic City convention, the way that Humphrey’s speech took a lot of the media oxygen away from the Mississippi credentials vote. It’s also true that aside from a few exceptions, the dominant national newspapers, all white-owned, paid far less attention to Vaughn’s speech than Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro-American did.

But the effects can still be traced. “The Mississippi issue had cleared the air,” Hamilton recalled years later in an unpublished autobiography. “That moment was the historic crisis which drew the party together.” It would be more accurate to say it was a crisis that carved the New Deal coalition apart, separating the multiracial urban liberals who remain a staple of the Democratic Party today and the group that passed from being Dixiecrats to Reagan Republicans to Donald Trump supporters. In that respect, too, the war of 1948 is still being waged.

Adapted from Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights by Samuel G. Freedman. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(3050x2149:3051x2150)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/84/3484d08c-1488-486f-be4a-9c3861c3aa37/gettyimages-1220874769_1.jpg)