Diving for the Secrets of the Battle of the Atlantic

Off the coast of North Carolina lie dozens of shipwrecks, remainders of a forgotten theater of World War II

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shipwrecks-Hoyt-and-U701-631.jpg)

It’s a World War II campaign largely forgotten, a coastal reign of terror Joe Hoyt and a team of marine archaeologists are determined to bring into sharp focus 70 years later.

During the first six months of 1942, German U-boats, often hunting in wolf packs, sank ship after ship just miles off the East Coast of the United States, concentrating their ambushes along North Carolina, where conditions were most favorable. From the beaches, civilians could see the explosions as the submarines sank more Allied tonnage in those months than the entire Japanese Navy would destroy in the Pacific during the entire course of the war.

German submariners dubbed it the “American Shooting Season.” While estimates of the carnage vary according to where boundaries are drawn, one survey concluded that 154 ships were sunk and more than 1,100 lives lost off the North Carolina coast in that period.

“It’s always surprised me that it’s not something everyone knows. It was the closest war came to the continental United States,” says Hoyt, a marine archaeologist with the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary staff in Newport News, Virginia. “For six months, there were sinkings nearly every day off the coast. We think it’s an important part of American history.”

Flowing like massive rivers in the sea, the cold-water Labrador Current from the north and the warm Gulf Stream from the south converge just off Cape Hatteras. To take advantage of these currents, vessels must draw close to the Outer Banks. This area off the North Carolina coast is a bottleneck where U-boat commanders knew they’d find plenty of prey. In addition, the Continental Shelf comes close to shore, offering deep water nearby where they could attack and hide.

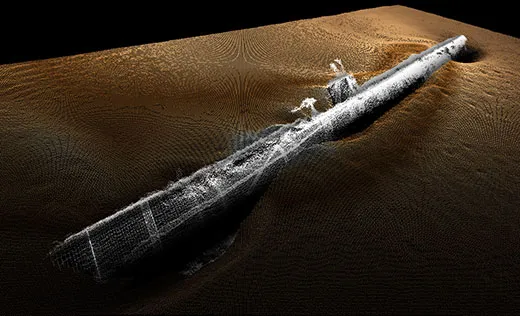

Hoyt says 50 to 60 Allied, Axis and merchant vessel wrecks rest off the North Carolina coast. Hoyt has led teams of NOAA researchers for four summers looking for and surveying wrecks from those World War II battles. A sonar survey last year revealed 47 potential sites. Whether they are 1942 wrecks, ruins from another time or just geologic anomalies will require further research. The project’s ultimate goals are to produce a comprehensive report on the wartime shipwrecks, create detailed models of the locations and channel the findings into museum exhibits or film productions. Key to that is the video work by a team of 3-D camera operators from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution using both divers and remote vehicles rigged with cutting-edge equipment.

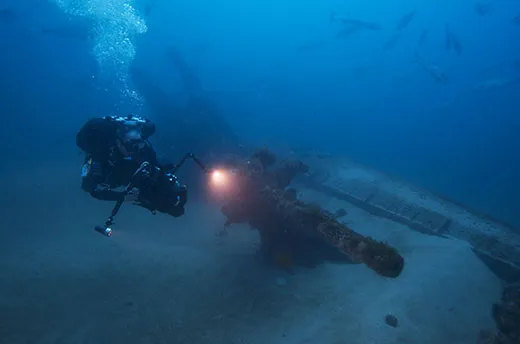

The 3-D cameras don’t just produce dramatic video; they also allow researchers to create detailed models of wreck sites from the comfort of their offices, without extensive measuring on the seabed. Because their lenses are offset providing three points to determine where something is in space, the cameras create thousands of stereo still images that become a digital data set researchers use to build detailed, highly accurate create models of wreck sites.

“It can help you learn about how the actual engagement took place,” Hoyt says. “You can look at torpedo damage or collision damage. You only see one section at a time when you’re underwater. You’re not able to step back and see the whole thing because of the water quality. So we try to create through video or a photo mosaic an overall image so you can get a good conceptualization of the site.”

Evan Kovacs, director of 3-D photography for Woods Hole, has been photographing wrecks, including the USS Monitor and the HMS Titanic, for more than a decade. “One of the greatest things about 3D from a storytelling perspective is its immersive quality,” Kovacs says. “You’re able to bring people there. You’re underwater, surrounded by sharks. There’s all of the innards and guts of the ships. It’s going to be pretty spectacular.”

Hoyt wants to do more than create models of individual wreck sites; he wants to map where battles took place and understand why they happened there. “We’re looking at the collection of wrecks out there in the landscape and how they tell a story of why this area was significant and why it was seized upon by U-boat commanders as a good place to operate,” he adds.

One battle Hoyt and his team were searching for took place on the afternoon of July 15, 1942. KS-520—a convoy of 19 merchant ships headed from Hampton, Virginia, to Key West, Florida–steamed about 20 miles off the North Carolina coast with war supplies. U-boats, at times hunting in wolf packs, had been viciously attacking the shipping lanes, especially off Cape Hatteras, sending 154 vessels to the sea floor along the East Coast.

Escorting the convoy were five naval vessels, two Kingfisher floatplanes and a blimp. Lying in wait was the U-576, a 220-foot-long German submarine that had been attacked days earlier, suffering damage to its ballast tank. But Hans-Dieter Heinicke, its commander, couldn’t resist attacking, firing four bow torpedoes. Two struck the Chilore, an American merchant ship. One hit the J.A. Nowinckel, a Panamian tanker, and the fourth tore into the Bluefields, a Nicaraguan merchant ship loaded with kapok (a ceiba tree product), burlap and paper. Within minutes, the Bluefields went to the bottom.

Just after firing, the U-576 popped to the surface only a few hundred yards from the Unicoi, an armed merchant vessel that fired upon it. The Kingfisher aircraft dropped depth charges and soon after sailors from the convoy saw the U-boat upend, props spinning out of the water, and spiral to the bottom.

Hoyt thinks it could be the only site off the coast where an Allied vessel and a German U-boat sank so close to each other. “It’s my hope that we have already gotten a ping on one of those, but it’s a matter of getting back, getting detailed imagery or an assessment of the site to be able to identify them,” he adds.

The team extensively filmed the wreck of the U-701 in 100 feet of water. In June 1942, the submarine set 15 mines in the approaches to the Chesapeake Bay, Hampton Roads and the Baltimore Harbor resulting in the damaging or sinking of five ships, including a destroyer, a trawler, and two tankers. On the afternoon of July 7, 1942, the U-701 surfaced to air its interior and was spotted by an A-29 bomber, which dropped three depth charges, tearing open the hull of the diving submarine and sending it to a watery grave.

The NOAA team surveyed the Diamond Shoals site, an area of high currents and shifting sands. “In 2008, the boat was almost completely covered,” Hoyt says. “Now, it’s totally exposed so we’re seeing a lot more of the wreck. We’re also learning because it’s been covered up for so long that it’s much more well preserved than some of the other sites.”

Seventy years later even on the bottom, the relic remains fearsome. The conning tower rises above the rest of the wreck, giving it an ominous profile. “It’s incredible,” Kovacs says. “You’re looking at the old killer of the sea. You can see figuratively and literally how this thing would strike fear.”

“Forgetting about what really happened,” he adds, “is not something we should be allowed to do.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/jim-morrison-240.jpg)