The Doctor Who Starved Her Patients to Death

Linda Hazzard killed as many as a dozen people in the early 20th century, and they paid willingly for it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ef/98/ef983d42-a640-4187-8e2d-ef788624901e/dr-hazzard-box.jpg)

Today the little town of Olalla, a ferry’s ride across Puget Sound from Seattle, is a mostly forgotten place, the handful of dilapidated buildings a testament to the hardscrabble farmers, loggers and fisherman who once tried to make a living among the blackberry vines and Douglas firs. But in the 1910s, Olalla was briefly on the front page of international newspapers for a murder trial the likes of which the region has never seen before or since.

At the center of the trial was a woman with a formidable presence and a memorable name: Dr. Linda Hazzard. Despite little formal training and a lack of a medical degree, she was licensed by the state of Washington as a “fasting specialist.” Her methods, while not entirely unique, were extremely unorthodox. Hazzard believed that the root of all disease lay in food—specifically, too much of it. “Appetite is Craving; Hunger is Desire. Craving is never satisfied; but Desire is relieved when Want is supplied,” she wrote in her self-published 1908 book Fasting for the Cure of Disease. The path to true health, Hazzard wrote, was to periodically let the digestive system “rest” through near-total fasts of days or more. During this time, patients consumed only small servings of vegetable broth, their systems “flushed” with daily enemas and vigorous massages that nurses said sometimes sounded more like beatings.

Despite the harsh methods, Hazzard attracted her fair share of patients. One was Daisey Maud Haglund, a Norwegian immigrant who died in 1908 after fasting for 50 days under Hazzard’s care. Haglund left behind a three-year-old son, Ivar, who would later go on to open the successful Seattle-based seafood restaurant chain that bears his name. But the best-remembered of Hazzard’s patients are a pair of British sisters named Claire and Dorothea (known as Dora) Williamson, the orphaned daughters of a well-to-do English army officer.

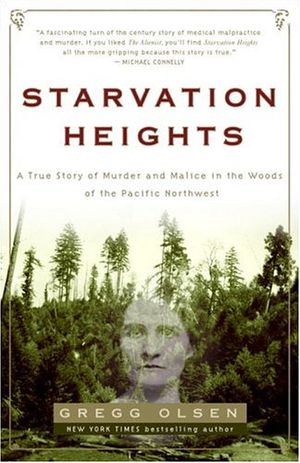

As Olalla-based author Gregg Olsen explains in his book Starvation Heights (named after the locals’ term for Hazzard’s institute), the sisters first saw an ad for Hazzard’s book in a newspaper while staying at the lush Empress Hotel in Victoria, British Columbia. Though not seriously ill, the pair felt they were suffering from a variety of minor ailments: Dorothea complained of swollen glands and rheumatic pains, while Claire had been told she had a dropped uterus. The sisters were great believers in what we might today call “alternative medicine,” and had already given up both meat and corsets in an attempt to improve their health. Almost as soon as they learned of Hazzard’s Institute of Natural Therapeutics in Olalla, they became determined to undergo what Claire called Hazzard’s “most beautiful treatment.”

The institute’s countryside setting appealed to the sisters almost as much as the purported medical benefits of Hazzard’s regimen. They dreamed of horses grazing the fields, and vegetable broths made with produce fresh from nearby farms. But when the women reached Seattle in February 1911 after signing up for treatment, they were told the sanitarium in Olalla wasn’t quite ready. Instead, Hazzard set them up in apartment on Seattle’s Capitol Hill, where she began feeding them a broth made from canned tomatoes. A cup of it twice a day, and no more. They were given hours-long enemas in the bathtub, which was covered with canvas supports when the girls started to faint during their treatment.

By the time the Williamsons were transferred to the Hazzard home in Olalla two months later, they weighed about 70 pounds, according to one worried neighbor. Family members would have been worried too, if any of them had known what was going on. But the sisters were used to family disapproving of their health quests, and told no one where they were going. The only clue something was amiss came in a mysterious cable to their childhood nurse, Margaret Conway, who was then visiting family in Australia. It contained only a few words, but seemed so nonsensical the nurse bought a ticket on a boat to the Pacific Northwest to check up on them.

Dr. Hazzard’s husband Samuel Hazzard (a former Army lieutenant who served jail time for bigamy after marrying Linda) met Margaret in Vancouver. Aboard the bus to their hotel, Samuel delivered some startling news: Claire was dead. As Dr. Hazzard later explained it, the culprit was a course of drugs administered to Claire in childhood, which had shrunk her internal organs and caused cirrhosis of the liver. To hear the Hazzards tell it, Claire had been much too far gone for the “beautiful treatment” to save her.

Margaret Conway wasn’t trained as a doctor, but she knew something was amiss. Claire’s body, embalmed and on display at the Butterworth mortuary near Pike Place Market, looked like it belonged to another person—the hands, facial shape, and color of the hair all looked wrong to her. Once she was in Olalla, Margaret discovered that Dora weighed only about 50 pounds, her sitting bones protruding so sharply she couldn’t sit down without pain. But she didn’t want to leave Olalla, despite the fact that she was clearly starving to death.

The horrors revealed in Dora’s bedroom were matched by the ones in Hazzard’s office: the doctor had been appointed the executor of Claire’s considerable estate, as well as Dora’s guardian for life. Dora had also signed over her power of attorney to Samuel Hazzard. Meanwhile, the Hazzards had helped themselves to Claire’s clothes, household goods, and an estimated $6,000 worth of the sisters’ diamonds, sapphires and other jewels. Dr. Hazzard even delivered a report to Margaret concerning Dora’s mental state while dressed in one of Claire’s robes.

Margaret got nowhere trying to convince Dr. Hazzard to let Dora leave. Her position as a servant hindered her—she often felt too timid to contradict those in a class above her—and Hazzard was known for her terrible power over people. She seemed to hypnotize them with her booming voice and flashing dark eyes. In fact, some wondered if Hazzard’s interest in spiritualism, theosophy and the occult had given her strange abilities; perhaps she hypnotized people into starving themselves to death?

In the end it took the arrival of John Herbert, one of the sisters’ uncles, whom Margaret had summoned from Portland, Oregon, to free Dora. After some haggling, he paid Hazzard nearly a thousand dollars to let Dora leave the property. But it took the involvement of the British vice consul in nearby Tacoma—Lucian Agassiz—as well as a murder trial to avenge Claire’s death.

As Herbert and Agassiz would discover once they started researching the case, Hazzard was connected to the deaths of several other wealthy individuals. Many had signed large portions of their estates over to her before their deaths. One, former state legislator Lewis E. Radar, even owned the property where her sanitarium was located (its original name was “Wilderness Heights”). Rader died in May 1911, after being moved from a hotel near Pike Place Market to an undisclosed location when authorities tried to question him. Another British patient, John “Ivan” Flux, had come to America to buy a ranch, yet died with $70 to his name. A New Zealand man named Eugene Wakelin was also reported to have shot himself while fasting under Hazzard’s care; Hazzard had gotten herself appointed administer of his estate, draining it of funds. In all, at least a dozen people are said to have starved to death under Hazzard’s care, although some claim the total could be significantly higher.

On August 15, 1911, Kitsap County authorities arrested Linda Hazzard on charges of first-degree murder for starving Claire Williamson to death. The following January, Hazzard’s trial opened at the county courthouse in Port Orchard. Spectators crowded the building to hear servants and nurses testify about how the sisters had cried out in pain during their treatments, suffered through enemas lasting for hours, and endured baths that scalded at the touch. Then there was what the prosecution called “financial starvation”: forged checks, letters, and other fraud that had emptied the Williamson estate. To make matters darker, there were rumors (never proven) that Hazzard was in league with the Butterworth mortuary, and had switched Claire’s body with a healthier one so no one could see just how skeletal the younger Williamson sister had been when she died.

Hazzard herself refused to take any responsibility for Claire’s death, or the deaths of any of her other patients. She believed, as she wrote in Fasting for the Cure of Disease, that “[d]eath in the fast never results from deprivation of food, but is the inevitable consequence of vitality sapped to the last degree by organic imperfection.” In other words, if you died during a fast, you had something that was going to kill you soon anyway. In Hazzard’s mind, the trial was an attack on her position as a successful woman, and a battle between conventional medicine and more natural methods. Other names in the natural health world agreed, and several offered their support during their trial. Henry S. Tanner, a doctor who fasted publicly for 40 days in New York City in 1880, offered to testify in order to “hold up the [conventional] medical fraternity to the derision of the world.” (He was never given the chance.)

Though extreme, Hazzard’s fasting practice drew on a well-established lineage. As Hazzard noted in her book, fasting for health and spiritual development is an ancient idea, practiced by both yogis and Jesus Christ. The ancient Greeks thought demons could enter the mouth during eating, which helped encourage the idea of fasting for purification. Pythagoras, Moses and John the Baptist all recognized the spiritual power of the fast, while Cotton Mather thought prayer and fasting would solve the Salem "witchcraft" epidemic.

The practice experienced a revival in the late-19th century, when a doctor named Edward Dewey wrote a book called The True Science of Living, in which he said that "every disease that afflicts mankind [develops from] more or less habitual eating in excess of the supply of gastric juices." (He also advocated what he called the “no-breakfast plan.”) Dewey's patient and later publisher, Charles Haskel, declared himself "miraculously cured" after a fast, and his own book, Perfect Health: How to Get It and How to Keep It, helped promote the idea of starving yourself for your own good. Even Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, got into the act with his non-fiction book The Fasting Cure, published in 1911. And the idea of fasting your way into health is still around, of course: today there are juice cleanses, extreme calorie deprivation diets, and the breatharians, who try to live on light and air alone.

Back in 1911, the jury in Hazzard’s trial was unmoved by her claims of politically motivated persecution. After a short period of deliberation, they returned a verdict of manslaughter. Hazzard was sentenced to hard labor at the penitentiary in Walla Walla, and her medical license revoked (for reasons unknown, she was later pardoned by the governor, although her license was never reinstated) She served two years, fasting in prison to prove the value of her regimen, and then moved to New Zealand to be near supporters. In 1920, she returned to Olalla to finally build the sanitarium of her dreams, calling the building a “school for health.”

The institute burned to the ground in 1935, and three years later, Hazzard, then in her early ’70s, fell ill and undertook a fast of her own. It failed to restore her to health, and she died shortly thereafter. Today, all that remains of her sanitarium are a 7-foot-tall concrete tower and the ruins of the building’s foundation, both now choked with ivy. The location of her downtown Seattle offices, the Northern Bank and Trust building at Fourth and Pike, still stands, the shoppers and tourists that swarm the streets below blissfully unaware of the schemes once plotted above.

Starvation Heights: A True Story of Murder and Malice in the Woods of the Pacific Northwest