It was the afternoon of December 3, 1942, and a vicious winter storm was thrashing boats along the Eastern Seaboard. U.S. Navy and Coast Guard listening stations were picking up urgent distress signals up and down the coast. A 71-foot schooner called the Nordlys, fighting 60-foot waves, had lost its sails to 50-knot winds. A sailboat called the Abenaki was completely adrift and at the mercy of the storm after its tiller was destroyed. The crew of a boat called the Tradition radioed a possible farewell: “This may be our last transmission.”

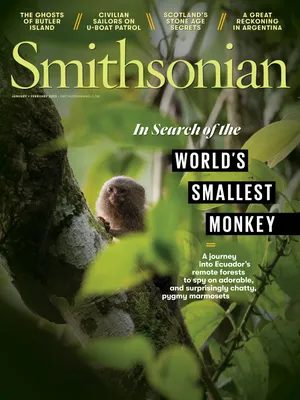

Sailboats had no business being out in such weather, but that calculus didn’t apply to those serving in the Coastal Picket Force, a motley assortment of privately owned vessels, from luxury schooners to battered fishing boats, that had been called into wartime service. Manned by hastily recruited citizen sailors, the Picket Force was tasked with patrolling American waters from Maine to Florida and along the West Coast. Its primary objective in the Atlantic: to spot and report German U-boats, which were wreaking havoc on Allied ships. In May alone, the Nazi submarine fleet sank 115 ships in the western Atlantic.

The mariners aboard the vessels of the Picket Force could hardly take out enemy submarines; they carried little more than guns. They could, however, report U-boat positions, neutralizing the German vessels’ essential advantage: stealth. But most of the American boats, designed for fishing or weekend cruises, were unequipped for winter conditions in the North Atlantic, let alone a storm witnesses later described as a combination blizzard and hurricane.

Now one of the smaller crafts in the civilian fleet was trapped in the tempest: a sleek 57-foot sailboat called the Zaida. The boat’s nine-man crew struggled for hours as the storm battered the yacht, throwing it off its position near Martha’s Vineyard. As the winds intensified, the men watched the mainmast bend feebly, with wave after wave drenching the ship’s deck and flooding into the cabin.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/85/f48520ee-a631-4b8f-a335-69f4f1474d92/janfeb2025_g06_hooligans.jpg)

The crew, captained by Curtis Arnall, a 45-year-old professional actor, debated their options, none of them good. They could use the smaller storm sail to try to head west for land, but this would require sailing into the gale, and they had trouble enough just staying afloat. Or they could take down all the sails and try to ride out the tempest, keeping the Zaida under control as best they could for as long as possible.

Any disagreement was settled by the sea. In an instant, the wind tore the rigging from the smaller mast, turning the yacht nearly on its side and into an incoming wave. The men below deck were thrown across the cabin, followed by a rush of water that hissed against the tiny onboard stove, filling the cramped space with smoke.

The upheaval threw James Watson, a fisherman and seal hunter by trade, against a bunk, breaking at least two of his ribs. Joe Choate, a former banker and experienced weekend sailor, smashed headfirst into a handrail, opening a bloody gash down his forehead. A third crew member was also hit on the head. Moments later, the sailboat righted itself, but there was no time to assess injuries—the crew had to bail out the Zaida before it sank. For nearly two hours they used pots and pans to empty water out of the cabin.

Eventually they were able to take stock of their situation. On top of the injuries and shredded sails, the Zaida had lost the smaller of its two masts, and its life raft had been swept away. The boat’s generator was waterlogged and useless, and the ship-to-shore radio’s batteries were drained from so many attempts to reach help. The crew was nevertheless able to make contact with a B-25 bomber sent to search for vessels despite the treacherous weather. Their message was delivered by blinking Morse code with a lamp: The boat had suffered extensive damage, and three men were injured. The bomber reported the Zaida’s location, but no boats on the water could reach it.

Other Picket Force vessels caught in the storm were either rescued or slowly made their way back into harbor. Not the Zaida. Over the next few days, almost a dozen Army bombers and 14 Canadian planes helped search for the yacht. Inbound ship convoys from Europe were told to keep an eye out.

The search for the Zaida became one of the most extensive in Navy history. By December 8, a Navy gunboat sent a discouraged update to Coast Guard headquarters: “Considering all factors it is our opinion chances yawl still afloat remote.”

The United States had been at war for less than a year when the Zaida set out on its mission, but the country was already badly losing the Battle of the Atlantic. German U-boats had been laying waste to American vessels along the Eastern Seaboard and into the Gulf of Mexico. Suddenly fighting a war on two oceans, the U.S. Navy simply didn’t have the resources to patrol more than 2,000 miles of Atlantic coastline.

Ships carrying fuel and weapons to support the war in Europe were easy targets for U-boats lurking offshore. Over the course of just 12 days, a single submarine known as U-507 sank eight cargo vessels in the Gulf of Mexico. German submarine commanders called this period eine glückliche Zeit—“a happy time.” Wreckage, oil and human remains washed up on beaches from South Florida to Long Island, New York, and horrified civilians watched from Atlantic City’s boardwalk as German subs pursued and sank merchant ships in broad daylight. The psychological toll on the home front was so severe that the War Department suppressed the numbers of submarine-related sinkings in order to avoid a panic. U-boats even came close enough to the shore to land sabotage teams on Long Island and the coast of Maine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ab/38/ab388525-51e2-4786-a76c-f0ff429e338e/janfeb2025_g10_hooligans.jpg)

Shutting down ship lights at night did little to protect Allied vessels, since German sub captains could easily make out ship silhouettes created by bright lights on shore. That summer the Germans sank two ships so close to Virginia Beach that the destroyed vessels were visible to beachgoers—a “macabre contrast of peace and war,” in the words of one Coast Guard veteran who was there. If the U-boat attacks continued, they could tip the scales of war.

Civilian mariners clamored to get into the fight. Look what the British had pulled off at Dunkirk, they argued, when hundreds of civilian ships helped evacuate close to 340,000 Allied soldiers from France as German forces were closing in. In the past, the U.S. Navy had employed private boats and crews in both the Civil War and World War I. American pilots with the Civil Air Patrol were already supporting border and coastal patrols. In February 1942, Alfred Stanford, commodore of the Cruising Club of America, one of the country’s leading amateur sailing groups, sent a proposal to the Navy to use nonmilitary sailing vessels for anti-submarine patrols and rescue operations.

Navy officials, however, were wary of putting civilians directly in harm’s way. That opinion began to change in March as newspapers picked up the story of the Navy’s refusal, sparking a public outcry. The Navy organized the new fleet, which it called the Coastal Picket Force, under the aegis of the Coast Guard Temporary Reserve. To this day the fleet remains a little-known facet of America’s wartime history. Nearly everyone has heard of Rosie the Riveter. Not so much the Picket Force.

The fleet welcomed almost any kind of seaworthy vessel: sleek motor cruisers, weathered trawlers, cutters with mahogany cabins and wet bars. At the peak of the program, an estimated 2,000 boats were used, crewed by more than 5,000 sailors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cc/8f/cc8f7134-e727-44c7-abb2-cb5c041382a1/janfeb2025_g09_hooligans.jpg)

They came from all walks of life: from college students to taxi drivers, from grizzled swordfishers to former congressmen. The Boston Globe reported on a patrol boat crew that consisted of a newspaper photographer, an artist, a salesman, a garage mechanic and a butler. Many men had been rejected by the traditional armed forces because of their age, weight or conditions such as colorblindness or hearing impairments. The Coast Guard Temporary Reserve was less picky. Choate, the banker and the Zaida’s second-in-command, wrote that all a man needed to pass the physical exam was a “discernible heartbeat.”

Some enlistees were skilled blue-water sailors, while others had never been to sea. One volunteer recalled stopping at the New York Public Library en route to his interview for a crash course in nautical terms like “port,” “starboard” and “helm.” He emerged from the interview as a “seaman first class.” Even celebrities joined the effort. Ernest Hemingway patrolled off the coast of Florida in his beloved cabin cruiser the Pilar, and Humphrey Bogart offered up his yacht the Santana, sailing out of Newport Beach, California.

The sailboats in the force ranged from day cruisers to 150-foot racing yachts. As spotting vessels, they had several advantages over motorized craft. They weren’t limited by fuel reserves, and because they were silent they were harder for U-boats to detect, so they could get closer and report enemy positions more accurately using binoculars and eventually underwater microphones. (Submarines had to surface periodically to refresh their air and recharge their batteries.)

Based out of smaller home ports such as Greenport on Long Island, the Picket Force flotilla was known informally as the Corsair Fleet or, sometimes, the Hooligan Navy, an unsubtle nod to the ragtag collection of mariners at its core. Regular enlisted sailors looked at the mariners in this ersatz armada with suspicion, even derision, for their supposed lack of discipline and skill. The Walt Disney-designed insignia—Donald Duck as a pirate, complete with eyepatch, dagger and pistols—didn’t exactly engender confidence. But nobody could deny the men’s enthusiasm and gumption, and members of the Hooligan Navy came to embrace the nickname with pride.

Aboard the Zaida, the crew took their orders from Arnall. Originally from Cheyenne, Wyoming, Arnall had worked as a ranch hand before making his way to Broadway, where he played small roles until the Great Crash of 1929 shattered the theater industry. His next role was playing the radio voice of the swashbuckling space hero Buck Rogers. The gig brought Arnall a measure of fame and an ego to go with it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/38/b0/38b0534c-65c2-4de3-bdd4-0b05af63f18e/janfeb2025_g04_hooligans.jpg)

Arnall was one of several experienced sailors among the crew. There was 26-year-old Vance M. “Smitty” Smith, who swore so consistently that for years his daughter thought the white birds that flew along the coast were called “goddamn seagulls.” Edward Jobson, a sophomore at Williams College and, at 20, the youngest crew member, had worked as a sailor on the Zaida before the war. A friendly young Finnish American named Toivo “George” Koskinen was esteemed by the others for his sailing skills. The crew also included a taxi driver from Brooklyn, a Dartmouth College student, and a wiry fisherman and seal hunter with endless stories of peril at sea.

The Zaida itself had been designed by a renowned shipbuilder and launched in 1937. Constructed with teak decking, mahogany woodwork and masts made of Sitka spruce, the boat was a thoroughbred under sail—sleek, responsive and, above all, fast. After it was handed over to the Coast Guard Reserve, its fine trim and body were painted gray, and its official wartime designation, “CGR 3070,” was stenciled on the hull in large white characters.

On November 27, 1942, the Zaida sailed to its assigned station, a 15-square-mile patch of ocean some 50 miles offshore. Its orders for the seven-day patrol: Search for enemy subs around the clock, no matter the weather, and be ready to help with rescue operations if Allied ships were torpedoed. If the crew spotted a U-boat, they were to report their position on the ship-to-shore radio so that Navy boats or planes could take decisive action.

Because the sailboats were slower than motorboats, often alone and barely armed, the Nazis didn’t view them as worthy targets, especially since any attack would betray their location. Nevertheless, there were occasional confrontations. Off the coast of Maine, the Sally II and a U-boat watched each other warily, just out of gun range, for upwards of 15 minutes. Over a loudspeaker the German captain finally ordered the American boat not to report its position. The crew did anyway. Luckily the two vessels parted without incident. “They were looking for bigger game,” one crew member said later.

Other stories recounted German subs surfacing directly under Picket Force vessels to the surprise of both crews. Then there was the Nazi commander who reportedly berated a crew of Hooligan sailors directly, telling them to go home and stop playing soldier.

But daily life aboard Hooligan vessels tended to be more tedious than thrilling. The Zaida’s crew manned four-hour rotating shifts on watch, during which they would sometimes mistake whales or porpoises for surfacing U-boats. They fished for sharks with homemade hooks, radioed position updates to other patrol boats and Coast Guard stations, and kept an eye out for storm petrels, tiny birds that sailors say herald bad weather.

While the ships were equipped with potbelly stoves, and each man was given a heavy fleece-lined coat and gloves, these resources were little match for December weather far out at sea. Most of the time the men just tried to keep warm and waited for the next meal after a frigid shift on deck.

After the Zaida was slammed onto its side, with the storm still raging, the crew discovered the vessel was badly damaged—and several men were injured. Watson was the worst off. To protect him, the men tied him into his bunk so he wouldn’t be tossed about by the churning seas.

Within hours, however, hope sailed into view in the form of the HMCS Caldwell, a Canadian destroyer that pulled close enough to identify the stricken sailboat. The Canadian crew tried to attach a tow, but the waves made it impossible to get a line aboard the sailboat. To try to calm the surface, the Caldwell dumped heavy black bunker oil into the water, but this did little except cover the Zaida and its crew in thick, stinking grease. Finally, after half a dozen or so tries, the Zaida crew retrieved a towline. Koskinen was on deck, making sure the line stuck, when he was swept into the icy water. He managed to grab a lifeline and haul himself back on board.

With the towline now attached, the men braced themselves as the slack ran out and the Zaida jolted forward. The yacht began picking up speed, its hull smashing against the water. It was a precarious ride, but it appeared the crew would be saved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/82/17827a6a-6da5-4914-abdd-4d1bd6ab8cb9/janfeb2025_g08_hooligans.jpg)

But after some seven hours of towing the rope suddenly snapped. It was now just before midnight, and the boats were separated in the darkness. Without a working radio, there was nothing the crew of the Zaida could do. They were alone, helpless in the freezing rain and blinding winds.

Over the next few days, the Zaida’s crew fended off desperation with improvisation. They combined gasoline and motor oil to make a substitute for kerosene to power the cabin lamp. They fashioned a funnel out of sail canvas so they could capture rainwater to drink.

At a lull in the storm, the crew got to work patching torn sails and sewing on metal slides so they could be reattached to the remaining mast. The one small, makeshift sail they did have didn’t provide much power, but it gave the crew enough control that they could start sailing—gingerly, but at least purposefully—to the southwest, toward land.

Meanwhile, Smith and Koskinen were determined to get the radio working again, so they began to filter seawater out of the gasoline to try to restart the generator. By the morning of December 9, Arnall was able to transmit a brief message, which was picked up by a Coast Guard station on the mainland: “Condition favorable, three men injured.”

Hearing this, the men were not just baffled—some were furious. Smith was beside himself. What part of being injured and adrift was “favorable”? Did the skipper think this was a Buck Rogers episode, where the unflappable hero always pulls through in the end?

The crew already had their doubts about their commander, who had been described by another Greenport-based mariner as “a foul ball.” While out sailing just before the Zaida’s first official patrol, Arnall had tried to cut a corner around a channel buoy and ended up running the boat aground. And the skipper was proving to be strangely possessive, almost secretive, about things like radio reports, incoming messages and navigational details, going so far as to keep everything jotted on a notebook in his pocket. These episodes were concerning enough that after the Zaida’s first few outings, several sailors had requested to be transferred to other boats.

Now, according to one account, Smith began pacing about the cabin, muttering, “That man, that man.”

By the next morning, the Zaida had been at sea for two weeks in the heart of winter. The men slept only intermittently and ate dwindling rations of beans, rice and canned peaches. They had resorted to tearing out cabinets and other noncritical parts of the cabin to burn in the stove to stay warm.

The cumulative stress and calorie shortage were taking their toll. At one point Arnall ordered Koskinen to go aloft to affix the repaired sail into place. Koskinen responded that it couldn’t be done—he was too exhausted. When Arnall pressed, Koskinen got halfway up the mast before stopping and retreating back down to the deck. “Too weak,” he said.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/19/75/197597bf-04be-44f0-927b-ccaaa535b1b1/janfeb2025_g05_hooligans.jpg)

Three days later, hope returned. The Zaida was riding 40-foot waves about 300 miles east of Norfolk, Virginia, when the crew spotted a small Allied warship less than a mile away, heading straight for them. A larger destroyer appeared next.

It’s a miracle the Zaida wasn’t immediately blown out of the water. The destroyer initially mistook the wounded sailboat for a U-boat and sounded battle stations before realizing it was the lost Picket Force yacht.

The nine men rejoiced, but once again their relief was premature. The seas were too heavy for the much larger ships to get close enough to take the men aboard without smashing the sailboat. Moreover, it turned out the ships, escorting a convoy of freighters and tankers to support Allied campaigns in North Africa, were heading in the opposite direction, so towing was out of the question. And because the convoy had to maintain radio silence, the captain of the destroyer couldn’t tell anyone. He had found the boat that the whole world seemed to be looking for, but he couldn’t do anything to help.

For the next few hours, the wind pushed the sailboat like a child’s toy between two lines of convoy ships. At times the vessels were close enough that the crews could see each other’s faces, but all they could do was wave. The last Morse-coded message from the destroyer was simply: “Good luck.” Then the convoy faded into the fog.

Once again the Zaida was alone in the Atlantic, driven out to sea by storm after storm. The days and nights started to blur. Theodore Carlson, the taxi driver from Brooklyn, comforted himself by reading the Bible. The crew daydreamed about steakhouses in Manhattan as their rations shrank to a single cup of whatever was left per day. Their faces grew gaunt and their bodies weakened. Jobson, the college sophomore, fainted on deck, and Ward Weimar, the Dartmouth student, became too feeble to handle the wheel.

Tensions aboard the yacht edged toward a breaking point. One afternoon, after Arnall and Smith had argued over their latest point of friction, Arnall sat down in the cabin and took out his .38 caliber pistol, which he began cleaning in silence. When Smith stepped below deck and saw what Arnall was doing, he proceeded to take out his own gun, a .45, and started cleaning it as well. Nobody said a word, and the incident passed. Aware of his own short temper and afraid of doing something regrettable, Smith later asked Choate to hide his gun and never tell him where it was.

Smith was on watch the night of December 22 when he glimpsed a flash of color through the gloom—a red buoy, and the first sign of land in almost a month.

Suddenly, the dark shape of a Coast Guard patrol boat loomed barely 100 feet away. The men yelled and waved a flashlight, but the other vessel didn’t respond or change course. In desperation, Smith took out the Zaida’s automatic rifle and fired half a dozen tracer bullets over the other ship’s bow.

Unsurprisingly, the crew of the patrol boat thought they were under fire from a German submarine. They were maneuvering into attack position, guns ready, when they heard shouts in English. The ships drew close enough to identify each other. The Zaida’s crew finally learned where they were: off Cape Hatteras, in North Carolina’s Outer Banks—and on the edge of a minefield. In geographic terms, the Zaida was essentially home. But because of the minefield, the boat was in more danger than ever. The Navy ordered the crew to stay put.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/ab/49abe314-c38d-4304-acd3-5496d3eee1e2/untitled-1.jpg)

The next morning, under windless skies, the Zaida’s crew members, desperate to reach land and close to starvation, debated running the boat up on the beach, minefield or not. A silent tension hung in the air.

Then a blimp appeared, and their excitement spilled forth in hugs, shouts and laughter. Gathered on deck, the crew members waved and shouted with excitement. The blimp reported back to base—“Six men observed on deck, all gesturing wildly for food”—and lowered a package of emergency supplies on a line. When the crew brought it on board, they found raisins, chocolate bars and a note: “Your position reported. Sit tight. Help on way.”

Within an hour, nine rescue planes had appeared. A Coast Guard patrol boat pulled alongside, and the Zaida’s crew climbed aboard, where pots of beef stew were waiting in the galley. Then a heavy fog rolled in, forcing the crew to spend one last night on the water until conditions improved enough to tow the Zaida through the minefield and back to shore.

They landed at the hamlet of Ocracoke, North Carolina, on the morning of December 24. Hundreds of people lined the dock and nearby roads to welcome them. The bedraggled crew quickly boarded a plane to a naval air station in Brooklyn, where their family members were waiting, including Smith’s pregnant wife. Some had been grieving their loved ones, convinced they had been lost at sea. Others had clung stubbornly to hope.

The men who stepped off the plane were sun-browned, skinny and traumatized from their month-long, nearly 3,000-mile saga. The mood at the reunion was not festive. There was no shouting or laughing. Just handshakes, quiet embraces and a hurried effort by the military to get everybody home in time for Christmas.

During the following year, the Navy built more capable patrol vessels, and German submarines shifted their attention to operations farther from America’s shores. U-boat captains learned they could no longer attack with impunity up and down the Eastern Seaboard. As the threat from submarines decreased, the Coastal Picket Force was reduced by two-thirds, and it was discontinued at the end of the war. Miraculously, only one member of the Hooligan Navy was killed while serving, during a collision with a Dutch freighter.

In a letter to the Greenport Picket Force’s commanding officer, a Navy official applauded the civilian sailors’ “superb brand of seamanship”: “I will not go so far as to say our pickets go hunting for gales, but when the gales do come along, these sturdy little boats just take the storms as a matter of course and ride them out.” Newspaper accounts praised the Hooligan Navy as “iron men in wooden ships,” but most Americans were understandably focused on the wars being fought in Europe and the Pacific.

The fleet’s military impact on the Battle of the Atlantic remains an open question. There are no accounts of U-boats sunk directly because of a patrol boat sighting. But Robert Desh, a Coast Guard historian, says the Germans were forced to change their tactics after the Picket Force became operational. The presence of so many small craft limited the Germans’ ability to hunt, while reassuring merchant seamen that if they were targeted, an American craft would be there to scoop them out of the water. “It certainly had an influence on what the Germans were doing,” he says.

John Wilbur, an independent researcher who has studied the Coastal Picket Force for decades, offers a comparison with American submarine activity in the waters off Japan a few years later. The American subs were “very wary of small coastal craft,” he says. “Perhaps they were not the perfect answer, but sailboats were the best solution available in 1942 and 1943.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e1/cf/e1cf8f52-1ddd-4da2-845f-c72c7d9022b3/janfeb2025_g02_hooligans.jpg)

Despite everything the Zaida’s crew went through, most served through the end of the war. Some continued to sail for the rest of their lives. Arnall went on to own two commercial fishing vessels. Whenever he had a chance, he would tell anyone—neighborhood kids in Long Island, family friends, strangers in bars—about the Zaida and its harrowing tale of wartime survival.

Choate ran the National Boat Show in New York for 20 years. Jobson became a publishing executive and continued to sail, cruising and racing along the East Coast aboard his own boat, the Stormsvala—the Swedish name for a kind of storm petrel. The wartime experience also seemed to strengthen Weimar’s love of sailing. “It didn’t shake him up enough to get him off the ocean,” his son Charles recently recalled. For the rest of his life, Weimar seemed to have a special connection to the ocean, and to rough waters in particular. He settled in Brightwaters, New York, just off the Great South Bay, and whenever a storm rolled in he would sit and stare out to sea.

The Zaida is still berthed in Greenport, where its owner takes it out every summer. The gray paint is gone, but its owner keeps the Coast Guard Reserve number painted on the hull, and the boat has most of its original fittings. At 88, it is one of the few Hooligan vessels still sailing. During a recent overhaul, a rusty rifle bullet was found lodged in the ceiling, most likely trapped there when the boat was knocked over during the 1942 storm. It’s now in a frame on the cabin wall, a reminder of the yacht’s wartime service and astonishing ordeal.

:focal(2500x2738:2501x2739)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b5/46/b5464e05-81f0-4338-be39-e596577dbe0e/janfeb2025_g03_hooligans.jpg)