Election Day 1860

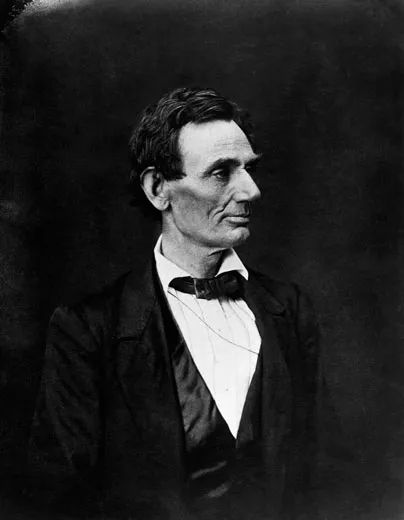

As soon as the returns were in, the burdens of the presidency weighed upon Abraham Lincoln

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lincolnelect_nov08_631.jpg)

The cannon salvo that thundered over Springfield, Illinois, at sunrise on November 6, 1860, signaled not the start of a battle, but the end of the bitter, raucous six-month-long campaign for president of the United States. Election Day was finally dawning. Lincoln probably awoke, like his neighbors, at the first cannon blast, if, that is, he had slept at all. Just a few days before, warning that "the existence of slavery is at stake," South Carolina's Charleston Mercury had called for a prompt secession convention in "each and all of the Southern states" should the "Abolitionist white man" capture the White House. That same day, a prominent New York Democrat prophesied that if Lincoln were elected, "at least Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina would secede."

Yet the danger that a Lincoln victory could prove cataclysmic did little to deflate the city's celebratory mood. By the time the polls opened at 8 a.m., a journalist reported, "tranquility forsook Springfield" altogether, and "the out-door tumult" awoke "whatever sluggish spirits there might be among the populace."

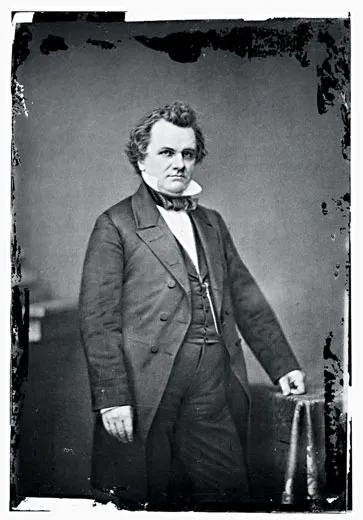

Less than three weeks earlier, Lincoln had confided to a caller that he would have preferred a full term in the Senate, "where there was more chance to make reputation and less danger of losing it—than four years in the presidency." It was a startling admission. But having lost two senatorial races over the past five years, most recently to Stephen A. Douglas—one of the two Democrats he now opposed in his run for the White House—Lincoln's conflicted thoughts were understandable.

Looking at his electoral prospects coolly he had reason to expect he would prevail. In a pivotal state election two months earlier, widely seen as a harbinger of the presidential contest, Maine had elected a Republican governor with a healthy majority. Republicans had earned similarly impressive majorities in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. Lincoln finally allowed himself to believe that the "splendid victories... seem to fore-shadow the certain success of the Republican cause in November."

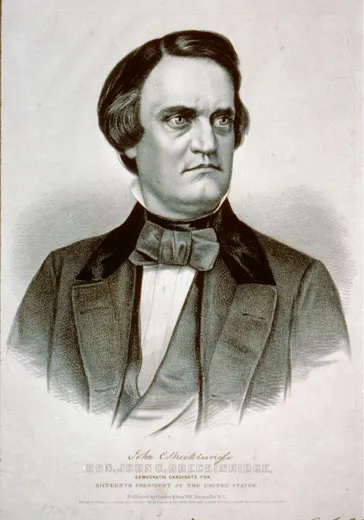

Complicating matters was the fact that four candidates were competing for the presidency. Earlier in the year, the sectionally riven Democratic Party had split into Northern and Southern factions, promising a dilution of its usual strength, and a new Constitutional Union Party had nominated Tennessee politician John Bell for president. Though Lincoln remained convinced that no "ticket can be elected by the People, unless it be ours," no one could be absolutely certain that any candidate would amass enough electoral votes to win the presidency outright. If none secured an absolute majority of electors, the contest would go to the House of Representatives. Anything might yet happen.

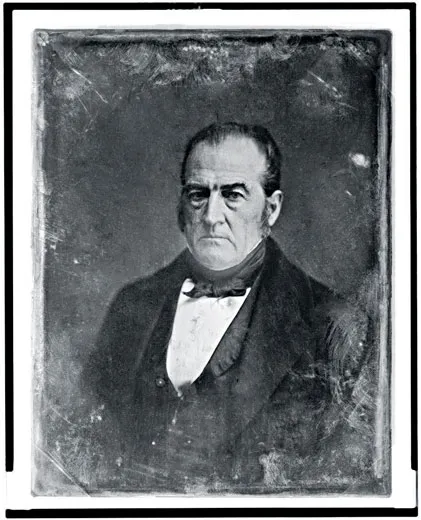

Stephen A. Douglas, the presidential standard-bearer of Northern Democrats, took care to deny that he harbored hopes for such an outcome, but privately dreamed of it. Outgoing President James Buchanan's endorsed choice, Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, had improbably emerged as the Democratic favorite in the president's home state of Pennsylvania, where "Old Buck" still enjoyed popularity. In New York, opposition to Lincoln coalesced around Douglas. Horace Greeley, editor of the pro-Lincoln New York Tribune, exhorted the Republican faithful to allow no "call of business or pleasure, any visitation of calamity, bereavement, or moderate illness, to keep you from the polls."

Despite the lingering uncertainty, Lincoln had done next to nothing publicly, and precious little privately, to advance his own cause. Prevailing political tradition called for silence from presidential candidates. In earlier elections, nominees who had defied custom appeared desperate and invariably lost. Besides, when it came to the smoldering issue of slavery, the choice seemed clear enough. Douglas championed the idea that settlers in new Western territories were entitled to vote slavery up or down for themselves, while Breckinridge argued that slave owners could take their human property anywhere they chose. Against both stood Lincoln.

Such profound disagreement might have provided fodder for serious debate. But no such opportunities existed within the reigning political culture of mid-19th-century America, not even when the canvass involved proven debaters like Lincoln and Douglas, who had famously battled each other face to face in seven senatorial debates two years earlier. Worried that Lincoln might be tempted to resume politicking, William Cullen Bryant, editor of the pro-Republican New York Evening Post, bluntly reminded him that "the vast majority of your friends...want you to make no speeches, write no letters as a candidate, enter into no pledges, make no promises, nor even give any of those kind words which men are apt to interpret into promises." Lincoln had obliged.

He was already on record as viewing slavery as "a moral, political and social wrong" that "ought to be treated as a wrong...with the fixed idea that it must and will come to the end." These sentiments alone had proven enough to alarm Southerners. But Lincoln had never embraced immediate abolition, knowing that such a position would have isolated him from mainstream American voters and rendered him unelectable. Unalterably opposed to the extension of slavery, Lincoln remained willing to "tolerate" its survival where it already existed, believing that containment would place it "in the course of ultimate extinction." That much voters already knew.

When a worried visitor from New England nonetheless urged him, the day before the election, to "reassure the men honestly alarmed" over the prospect of his victory, Lincoln flew into a rare fury, and, as his personal secretary John George Nicolay observed, branded such men "liars and knaves." As Lincoln hotly explained: "This is the same old trick by which the South breaks down every Northern victory. Even if I were personally willing to barter away the moral principle involved in this contest, for the commercial gain of a new submission to the South, I would go to Washington without the countenance of the men who supported me and were my friends before the election; I would be as powerless as a block of buckeye wood."

In the last letter of his noncampaign, composed a week before Election Day, one can hear the candidate refusing to be drawn into further debate: "For the good men of the South—and I regard the majority of them as such—I have no objection to repeat seventy and seven times. But I have bad men also to deal with, both North and South—men who are eager for something new upon which to base new misrepresentations—men who would like to frighten me, or, at least, to fix upon me the character of timidity and cowardice. They would seize upon almost any letter I could write, as being an 'awful coming down.' I intend keeping my eye upon these gentlemen, and to not unnecessarily put any weapons in their hands."

So Lincoln's "campaign" for president ended as it began: in adamant silence, and in the same Illinois city to which he had so tenaciously clung since the national convention. Like the solar eclipse that had obscured the Illinois sun in July, Lincoln remained in Springfield, hidden in full view.

Inside what one visiting reporter described as the "plain, neat looking, two story" corner house where he had lived with his family for 16 years, Lincoln prepared to accept the people's verdict. In his second-floor bedroom, he no doubt dressed in his usual formal black suit, pulling his long arms into a frock coat worn over a stiff white shirt and collar and a black waistcoat. As always, he wound a black tie carelessly round his sinewy neck and pulled tight-fitting boots—how could they be otherwise?—over his gargantuan feet. He likely greeted Mary and their two younger sons, 9-year-old Willie and 7-year-old Tad, at the dining table. (The eldest, Robert, had recently begun his freshman year at Harvard.)

Lincoln probably took his usual spare breakfast with the family—an egg and toast washed down with coffee. Eventually he donned the signature stovepipe hat he kept on an iron hook in the front hall. Then, as always—unaccompanied by retinues of security men or political aides—he stepped outside, turned toward the Illinois State Capitol some five blocks to the northwest and marched on toward his headquarters.

The bracing air that greeted Lincoln may have surprised—even worried—him. The unseasonable chill could dampen voter turnout. As the morning warmed, however, reports of sun-drenched, cloudless skies from one end of the state to the other stirred Republican hearts, clement weather being crucial to the task of enticing widely scattered rural voters, predominantly Republican, to distant polling places.

Once notorious for its muddy streets and freely roaming pigs, Springfield now boasted outdoor, gas-fed lighting; a large and growing population of lawyers, doctors and merchants; and clusters of two- and three-story brick structures surmounting wood-plank sidewalks.

Looming with almost incongruous grandeur over the city was the imposing State House, its red-painted copper cupola rising twice as tall as any other structure in town. Here, since his nomination in May, Lincoln had maintained his official headquarters—and his official silence—in a second-floor corner suite customarily reserved for the state's governor. For six months, Lincoln had here welcomed visitors, told "amusing stories," posed for painters, accumulated souvenirs, worked on selected correspondence and scoured the newspapers. Now he was headed there to pass his final hours as a candidate for president.

Lincoln entered the limestone State House from the south through its oversized pine doors. He ambled past its Supreme Court chamber, where he had argued many cases during his 24-year legal career, and past the adjacent libraries where he had researched the sensational speech he had delivered at Cooper Union nine months earlier in New York City. Then he climbed the interior staircase, at the top of which stood the ornate Assembly chamber where, in 1858, he had accepted the Republican Senate nomination with his rousing "House Divided" address.

Keeping his thoughts to himself as usual, Lincoln headed to a 15-foot-by-25-foot carpeted reception room and smaller adjacent office, simply furnished with both upholstered and plain wooden chairs, a desk and a table—ceded to him these many months by the new governor, John Wood.

Here the journalists who arrived to cover Lincoln's movements this Election Day encountered the candidate, "surrounded by an abattis [sic] of disheveled newspapers and in comfortable occupancy of two chairs, one supporting his body, the other his heels." Entering the crowded room to a hearty "come in, sir," a New York newspaperman was struck by the candidate's "easy, old fashioned, off-handed manner," and was surprised to find "none of that hard, crusty, chilly look about him" that "dominated most campaign portraits." Doing his best to display his "winning manner" and "affability," Lincoln spent the early part of the day "receiving and entertaining such visitors as called upon him," respectfully rising each time a new delegation arrived. "These were both numerous and various—representing, perhaps as many tempers and as many nationalities as could easily be brought together at the West."

When, for example, "some rough-jacketed constituents" burst in, who, "having voted for him...expressed a wish to look at their man," Lincoln received them "kindly" until they "went away, thoroughly satisfied in every manner." To a delegation of New Yorkers, Lincoln feigned displeasure, chiding them that he would have felt better had they stayed home to vote. Similarly, when a New York reporter arrived to shadow him, he raised an eyebrow and scolded: "a vote is a vote; every vote counts."

But when a visitor asked whether he worried that Southern states would secede if he won, Lincoln turned serious. "They might make a little stir about it before," he said. "But if they waited until after the inauguration and for some overt act, they would wait all their lives." Unappreciated in the excitement of the hour was this hint at a policy of nonaggression.

On this tense day, Lincoln offered the hopeful view that "elections in this country were like 'big boils'—they caused a great deal of pain before they came to a head, but after the trouble was over the body was in better health than before." Eager as he was for the campaign to "come to a head," Lincoln delayed casting his own vote. As the clock ticked away, he remained secluded in the Governor's suite, "surrounded by friends...apparently as unconcerned as the most obscure man in the nation," occasionally glancing out the window to the crowded polling place across Capitol Square.

As Lincoln dawdled, more than four million white males began registering their choices for the presidency. In must-win New York, patrician lawyer George Templeton Strong, an ardent Lincoln supporter, sensed history in the making. "A memorable day," he wrote in his diary. "We do not know yet for what. Perhaps for the disintegration of the country, perhaps for another proof that the North is timid and mercenary, perhaps for demonstration that Southern bluster is worthless. We cannot tell yet what historical lesson the event of November 6, 1860, will teach, but the lesson cannot fail to be weighty."

The Virginia extremist Edmund Ruffin also wanted Lincoln to win—though for a different reason. Like many fellow secessionists, Ruffin hoped a Lincoln victory would embolden the South to quit the Union. Earlier that year, the agricultural theorist and political agitator had published a piece of speculative fiction entitled Anticipations of the Future, in which he flatly predicted that "the obscure and coarse Lincoln" would be "elected by the sectional Abolition Party of the North," which in turn would justify Southern resistance to "oppression and impending subjugation"—namely, a fight for "independence."

Several hundred miles to the north, in the abolitionist hotbed of Quincy, Massachusetts, Charles Francis Adams—Republican Congressional candidate, son of one American president, grandson of another and proud heir to a long family tradition of antislavery—proudly "voted the entire ticket of the Republicans," exulting: "It is a remarkable idea to reflect that all over this broad land at this moment the process of changing the rulers is peacefully going on and what a change in all probability." Even so, Adams had hoped for a different Republican—William Seward—to win the nomination.

Closer to Springfield—and perhaps truer to the divided spirit of America—a veteran of the Mexican War evinced conflicted emotions about the choices his Galena, Illinois, neighbors faced. "By no means a 'Lincoln man,' " Ulysses S. Grant nonetheless seemed resigned to the Republican's success. "The fact is I think the Democratic party want a little purifying and nothing will do it so effectually as a defeat," asserted the retired soldier, now starting life anew in the family's leather-tanning business. "The only thing is, I don't like to see a Republican beat the party."

In Stephen A. Douglas' hometown of Chicago, meanwhile, voters braved two-hour waits in lines four blocks long. But Douglas was not there to cast a vote of his own. On the southern leg of a multi-city tour, he found himself in Mobile, Alabama, where he may have taken solace that Lincoln's name did not even appear on that state's ballots—or, for that matter, on any of the nine additional Deep South states. The man who had beaten Lincoln for the Senate only two years earlier now stood to lose his home state—and with it, the biggest prize in American politics—to the very same man.

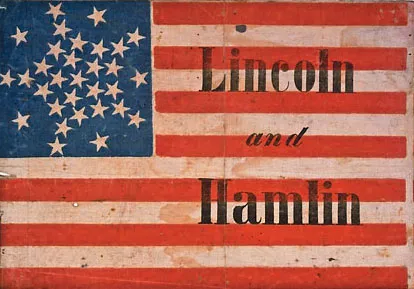

As of Election Day, Lincoln had successfully avoided not only his three opponents, but also his own running mate, Hannibal Hamlin. Republicans had nominated the Maine senator for vice president without Lincoln's knowledge or consent—true to another prevailing political custom that left such choices exclusively to the delegates—in an attempt to balance the ticket. After asking a mutual acquaintance to convey his "respects" to Hamlin a week after the convention, Lincoln waited a full two months before initiating direct communication. Even then, pointing out that both of them had served in the 30th Congress from 1847 to 1849—Lincoln as a congressman and Hamlin as a senator—Lincoln admitted, "I have no recollection that we were introduced." Almost grudgingly did he add: "It appears to me that you and I ought to be acquainted."

Now, on Election Day, the Republican Party's running mates would be voting much as they had "run": separately and silently.

Frederick Douglass was skeptical. Like Lincoln, the former slave turned passionate civil rights pioneer was self-educated, a brilliant writer and a captivating orator. And while both men rejected the idea that the Constitution gave Americans the right to own slaves, Douglass did not agree that the Constitution protected slavery in states where it had existed before the founding of the Republic or in Southern states that had joined the Union since. And while Douglass decried "threats of violence" against Republicans in Kentucky and other states "and the threats of dissolution of the Union in case of the election of Lincoln," he could not bring himself to praise Lincoln directly. Their warm personal acquaintance would not begin for several more years.

Springfield's actual polling place, set up in a courtroom two flights upstairs at the oblong-shaped Sangamon County Court House at Sixth and Washington streets, consisted of two partially enclosed "voting windows close beside each other," one for Democrats, one for Republicans. It was "a peculiar arrangement" in the view of the correspondent from St. Louis, but one that had been "practiced in Springfield for several years." A voter had only to pick up the preprinted ballot of his choice outside, and then ascend the stairs to announce his own name to an election clerk and deposit the ballot in a clear glass bowl. This was secret in name only: voters openly clutching their distinctly tinted, ornately designed forms while waiting in line signaled precisely how they intended to vote. The system all but guaranteed bickering and ill feelings.

In this roiling atmosphere, it was hardly surprising that Lincoln had replied almost defensively to a neighbor about how he planned to vote. "For Yates," he said—Richard Yates, the Republican candidate for governor of Illinois. But "How vote" on "the presidential question?" the bystander persisted. To which Lincoln replied: "Well...by ballot," leaving onlookers "all laughing." Until Election Day afternoon, Lincoln's law partner William Herndon was convinced that Lincoln would bow to the "feeling that the candidate for a Presidential office ought not to vote for his own electors" and cast no ballot whatsoever.

But around 3:30 p.m., he peered out the window toward the crowd surrounding the courthouse, slipped out of the Governor's Room, headed downstairs and "walked leisurely over to deposit his vote," accompanied by a small group of friends and protectors to "see him safely through the mass of men at the voting place."

As Lincoln reached the courthouse to cheers and shouts from surprised Republicans, "friends almost lifted him off the ground and would have carried him to the polls [but] for interference." The "dense crowd," Lincoln's future assistant secretary John M. Hay recalled, "began to shout with...wild abandon" even as they "respectfully opened a passage for him from the street to the polls." People shouted out "Old Abe!" "Uncle Abe!" "Honest Abe!" and "The Giant Killer!" Even Democratic supporters, Herndon marveled, "acted politely—civilly & respectfully, raising their hats to him as he passed on through them."

A New York Tribune reporter on the scene confirmed that "all party feelings seemed to be forgotten, and even the distributors of opposition tickets joined in the overwhelming demonstrations of greeting." Every Republican agent in the street fought for "the privilege of handing Lincoln his ballot." A throng followed him inside, John Nicolay reported, pursuing him "in dense numbers along the hall and up the stairs into the court room which was also crowded." The cheering that greeted him there was even more deafening than in the street, and once again came from both sides of the political spectrum.

After he "urged his way" to the voting table, Lincoln followed ritual by formally identifying himself in a subdued tone: "Abraham Lincoln." Then he "deposited the straight Republican ticket" after first cutting his own name, and those of the electors pledged to him, from the top of his preprinted ballot so he could vote for other Republicans without immodestly voting for himself.

Making his way back to the door, the candidate smiled broadly at well-wishers, doffing the black top hat that made him appear, in the words of a popular campaign song, "in h[e]ight somewhat less than a steeple," and bowed with as much grace as he could summon. Though the "crush was too great for comfortable conversation," a number of excited neighbors grabbed Lincoln by the hand or tried offering a word or two as he inched forward.

Somehow, he eventually made his way through this gantlet and back downstairs, where he encountered yet another throng of frenzied well-wishers. Now they shed all remaining inhibitions, "seizing his hands, and throwing their arms around his neck, body or legs and grasping his coat or anything they could lay hands on, and yelling and acting like madmen." Lincoln made his way back to the Capitol. By 4 p.m. he was safely back inside "his more quiet quarters," where he again "turned to the entertainment of his visitors as unconcernedly as if he had not just received a demonstration which anybody might well take a little time to think of and be proud over."

Even with the people's decision only hours away, Lincoln still managed to look relaxed as he exchanged stories with his intimates, perhaps keeping busy in order to remain calm himself. Samuel Weed thought it remarkable that "Mr. Lincoln had a lively interest in the election, but...scarcely ever alluded to himself." To hear him, noted Weed, "one would have concluded that the District Attorneyship of a county in Illinois was of far more importance than the Presidency itself." Lincoln's "good nature never deserted him, and yet underneath I saw an air of seriousness, which in reality dominated the man."

After four o'clock, telegrams bearing scattered early returns began trickling in, uniformly predicting Republican successes across the North. When one cantankerous dispatch expressed the hope that the Republican would triumph so his state, South Carolina, "would soon be free," Lincoln scoffed, recalling that he had received several such letters in recent weeks, some signed, others anonymous. Then his expression darkened and he handed the telegram to Ozias Hatch with the remark that its author, a former congressman, "would bear watching." Indirect as it was, this was the candidate's first expression that he expected soon to be president-elect, with responsibilities that included isolating potential troublemakers. Shortly thereafter, around 5 p.m. Lincoln walked home, presumably to take dinner. There he remained with his family for more than two hours.

When Lincoln returned to the state house around 7 to resume reading dispatches, he still displayed "a most marvelous equanimity." Down the corridor, inside the cavernous, gas-lit Representative Hall, nearly 500 Republican faithful massed for a "lively time." The chamber "was filled nearly all night," Nicolay recalled, by a crowd "shouting, yelling, singing, dancing, and indulging in all sorts [of] demonstrations of happiness as the news came in."

Weed distinctly remembered the candidate's silent but evocative reaction when the first real returns finally arrived. "Mr. Lincoln was calm and collected as ever in his life, but there was a nervous twitch on his countenance when the messenger from the telegraph office entered, that indicated an anxiety within that no coolness from without could repress." It turned out to be a wire from Decatur "announcing a handsome Republican gain" over the presidential vote four years earlier. The room erupted with shouts at the news, and supporters bore the telegram into the hallway "as a trophy of victory to be read to the crowd."

Further numbers proved agonizingly slow in coming.

The day before, the town's principal telegraph operator had invited Lincoln to await the returns at the nearby Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company headquarters, in whose second-floor office, the man had promised, "you can receive the good news without delay," and without "a noisy crowd inside." By nine o'clock, Lincoln could resist no longer. Accompanied by Hatch, Nicolay and Jesse K. Dubois, Lincoln strode across the square, ascended the stairs of the telegraph building and installed himself on a sofa "comfortably near the instruments."

For a time, the growing knot of onlookers notwithstanding, the small room remained eerily quiet, the only sounds coming from "the rapid clicking of the rival instruments, and the restless movements of the few most anxious among the party of men who hovered" around the wood-and-brass contraptions whose worn ivory keys pulsated magically.

At first the "throbbing messages from near and far" arrived in "fragmentary driblets," Nicolay remembered, then in a "rising and swelling stream of cheering news." Each time a telegraph operator transcribed the latest coded messages onto a mustard-colored paper form, the three-by-five-inch sheet was quickly "lifted from the table...clutched by some of the most ardent news-seekers, and sometimes, in the hurry and scramble, would be read by almost every person present before it reached him for whom it was intended."

For a while, the telegraph company's resident superintendent, John J. S. Wilson, grandly announced every result aloud. But eventually the telegraph operators began handing Lincoln each successive message, which, with slow-motion care, "he laid on his knee while he adjusted his spectacles, and then read and reread several times with deliberation." Despite the uproar provoked by each, the candidate received every piece of news "with an almost immovable tranquility." It was not that he attempted to conceal "the keen interest he felt in every new development," an onlooker believed, only that his "intelligence moved him to less energetic display of gratification" than his supporters. "It would have been impossible," another witness agreed, "for a bystander to tell that that tall, lean, wiry, good-natured, easy-going gentleman, so anxiously inquiring about the success of the local candidates, was the choice of the people to fill the most important office in the nation."

Lincoln had won Chicago by 2,500 votes, and all of Cook County by 4,000. Handing over the crucial dispatch, Lincoln said, "Send it to the boys," and supporters whisked it across the square to the State House. Moments later, cheering could be heard all the way to the telegraph office. The ovation lasted a full 30 seconds. Indiana reported a majority of "over twenty thousand for honest old Abe," followed by similarly good news from Wisconsin and Iowa. Pittsburgh declared: "Returns already recd indicate a maj for Lincoln in the city by Ten Thousand[.]" From the City of Brotherly Love came news that "Philadelphia will give you maj about 5 & plurality of 15" thousand. Connecticut reported a "10,000 Rep. Maj."

Even negative news from Southern states like Virginia, Delaware and Maryland left the nominee "very much pleased" because the numbers from these solidly Democratic strongholds might have been far worse. Notwithstanding this growing arsenal of good news, the group remained nervously impatient for returns from the swing state of New York, whose mother lode of 35 electoral votes might determine whether the election would be decided this very night or later in the uncertain House of Representatives. Then came a momentous report from the Empire State and its impulsive Republican chairman, Simeon Draper: "The city of New York will more than meet your expectations." Between the lines, the wire signaled that the overwhelmingly Democratic metropolis had failed to produce the majorities Douglas needed to offset the Republican tide upstate.

Amid the euphoria that greeted this news, Lincoln remained the "coolest man in that company." When the report of a probable 50,000-vote victory quickly followed from Massachusetts, Lincoln merely commented in mock triumph that it was "a clear case of the Dutch taking Holland." Meanwhile, with only a few intimates able to fit inside the modest telegraph office, crowds built in the square outside, where, the New York Tribune reported, rumors "of the most gigantic and imposing dimensions" began wildly circulating: Southerners in Washington had set fire to the capital. Jeff Davis had proclaimed rebellion in Mississippi and Stephen Douglas had been seized as a hostage in Alabama. Blood was running in the streets of New York. Anyone emerging from the telegraph station to deny these and kindred rumors was set down as having his own reasons for concealing the dreadful truth.

Shortly after midnight, Lincoln and his party walked to the nearby "ice cream saloon" operated by William W. Watson & Son on the opposite side of Capitol Square. Here a contingent of Republican ladies had set up "a table spread with coffee, sandwiches, cake, oysters and other refreshments for their husbands and friends." At Watson's, the Missouri Democrat reported, Lincoln "came as near to being killed by kindness as a man can conveniently be without serious results."

Mary Lincoln attended the collation, too, as "an honored guest." For a time, she sat near her husband in what was described as "a snug Republican seat in the corner," surrounded by friends and "enjoying her share of the triumph." A fervent political partisan in her own right who had viewed the October state results in both Indiana and Pennsylvania as extremely hopeful signs, Mary had become more anxious than her husband in the final days of the campaign. "I scarcely know, how I would bear up, under defeat," she had confided to her friend Hannah Shearer.

"Instead of toasts and sentiment," eyewitness Newton Bateman remembered, "we had the reading of telegrams from every quarter of the country." Each time the designated reader mounted a chair to announce the latest results, the numbers—depending on which candidate it favored—elicited either "anxious glances" or "shouts that made the very building shake." According to Bateman, the candidate himself read one newly arrived telegram from Philadelphia. "All eyes were fixed upon his tall form and slightly trembling lips, as he read in a clear and distinct voice: 'The city and state for Lincoln by a decisive majority,' and immediately added in slow, emphatic terms, and with a significant gesture of the forefinger: 'I think that settles it.' "

If the matter remained in doubt, the long-awaited dispatch from New York soon arrived with a tally that all but confirmed that Lincoln would indeed win the biggest electoral prize of the evening—and with it, the presidency. The celebrants instantly crowded around him, "overwhelming him with congratulations." Describing the reaction—in which "men fell into each other's arms shouting and crying, yelling like mad, jumping up and down"—one of the celebrants compared the experience to "bedlam let loose." Hats flew into the air, "men danced who had never danced before," and "huzzahs rolled out upon the night."

In the State House, "men pushed each other—threw up their hats—hurrahed—cheered for Lincoln...cheered for New York—cheered for everybody—and some actually laid down on the carpeted floor and rolled over and over." One eyewitness reported a "perfectly wild" scene, with Republicans "singing, yelling! Shouting!! The boys (not children) dancing. Old men, young, middle aged, clergymen, and all...wild with excitement and glory."

As church bells began pealing, Lincoln eased past the dense throng of Watson's well-wishers, "slipped out quietly looking grave and anxious," and headed back toward the telegraph office to receive the final reports.

He appeared to steel himself. One observer saw him pacing up and down the sidewalk before re-entering the Illinois & Mississippi building. Another glimpsed his silhouette, his head bowed to stare at the latest dispatch while "standing under the gas jets" that lit the streets. Back inside, wires from Buffalo sealed the state—and the White House—for the Republicans. The final telegram from New York ended with the words: "We tender you our congratulations upon this magnificent victory."

Though the crowd inside the telegraph office greeted this climactic news with lusty cheering, Lincoln merely stood to read the pivotal telegram "with evident marks of pleasure," then silently sank back into his seat. Jesse K. Dubois tried to break the tension by asking his old friend: "Well, Uncle Abe, are you satisfied now?" All Lincoln allowed himself to say was: "Well, the agony is most over, and you will soon be able to go to bed."

But the revelers had no intention of retiring for the night. Instead they emptied into the streets and massed outside the telegraph office, shouting "New York 50,000 majority for Lincoln—whoop, whoop hurrah!" The entire city "went off like one immense cannon report, with shouting from houses, shouting from stores, shouting from house tops, and shouting everywhere." Others reacted more solemnly. One of the final telegrams Lincoln received that night came from an anonymous admirer who signed himself only as "one of those who am glad today." It read: "God has honored you this day, in the sight of all the people. Will you honor Him in the White House?"

Abraham Lincoln won election as the 16th president of the United States by carrying every Northern state save New Jersey. No candidate had ever before taken the presidency with such an exclusively regional vote. In the end, Lincoln would amass 180 electoral votes in all—comfortably more than the 152 required for an absolute majority. Lincoln could also take comfort from the fact that the rapidly growing nation awarded him more popular votes than any man who had ever run for president—1,866,452 in all, 28,000 more votes than Democrat James Buchanan had earned in winning the presidency four years earlier. But Lincoln's votes amounted to a shade under 40 percent of the total cast, second only to John Quincy Adams as the smallest share ever collected by a victor. And the national tally alone did not tell the full story.

Testifying alarmingly to the deep rift cleaving North from South, and presaging the challenges soon to face his administration, was the anemic support Lincoln garnered in the few Southern states where his name was allowed to appear on the ballot. In Virginia, Lincoln received just 1,929 votes out of 167,223 cast—barely 1 percent. The result was even worse in his native Kentucky: 1,364 out of 146,216 votes cast.

Analyzed geographically, the total result gave Lincoln a decisive 54 percent in the North and West, but only 2 percent in the South—the most lopsided vote in American history. Moreover, most of the 26,000 votes Lincoln earned in all five slaveholding states where he was allowed to compete came from a single state—Missouri, whose biggest city, St. Louis, included many German-born Republicans.

Forced to "the lamentable conclusion that Abraham Lincoln has been elected President," the anti-Republican Washington Constitution forecast "gloom and storm and much to chill the heart of every patriot in the land....We can understand the effect that will be produced in every Southern mind when he reads the news this morning—that he is now called on to decide for himself, his children, and his children's children whether he will submit tamely to the rule of one elected on account of his hostility to him and his, or whether he will make a struggle to defend his rights, his inheritance, and his honor."

According to a visiting journalist, Springfield remained "alive and animated throughout the night." Rallies continued until dawn, growing so "uncontrollable" by 4 a.m. that revelers toted back the cannon with which they had inaugurated Election Day and now made it again "thunder rejoicings for the crowd." John Nicolay tried going to bed at 4:30 but "couldn't sleep for the shouting and firing guns." By most accounts, the celebrations ended only with daybreak.

No one is entirely sure when Lincoln himself finally retired. According to one eyewitness, he left the telegraph office for his house at 1:30 a.m.; according to another, shortly after 2. Not until 4:45 a.m. did the New York Tribune receive a final bulletin from its Springfield correspondent confirming that "Mr. Lincoln has just bid good-night to the telegraph office and gone home."

Moments before his departure, whenever it came, Lincoln at last received the final returns from his hometown—a matter about which he admitted he "did not feel quite easy," national victory notwithstanding. But Lincoln could take heart. Though he lost Sangamon County to Douglas by a whisker—3,556 to 3,598—he won the hotly contested city of Springfield by all of 22 votes. At this latest news, "for the first and only time" that night, Lincoln "departed from his composure, and manifested his pleasure by a sudden exuberant utterance—neither a cheer nor a crow, but something partaking of the nature of each"—after which he "contentedly" laughed out loud.

The president-elect thanked the telegraph operators for their hard work and hospitality, and stuffed the final dispatch from New York into his pocket as a souvenir. It was about time, he announced to one and all, that he "went home and told the news to a tired woman who was sitting up for him."

To several observers, Lincoln suddenly seemed graver—his thoughts far away. Nicolay could see the "pleasure and pride at the completeness of his success" melt into melancholy. The "momentary glow" of triumph yielded to "the appalling shadow of his mighty task and responsibility. It seemed as if he suddenly bore the whole world upon his shoulders, and could not shake it off." Even as the outer man continued absentmindedly studying final election returns, the "inner man took up the crushing burden of his country's troubles, and traced out the laborious path of future duties." Only later did Lincoln tell Gideon Welles of Connecticut that from the moment he allowed himself to believe he had won the election, he indeed felt "oppressed with the overwhelming responsibility that was upon him."

From "boyhood up," Lincoln had confided to his old friend Ward Hill Lamon, "my ambition was to be President." Now reality clouded the fulfillment of that lifelong dream. Amid "10,000 crazy people" outside, the president-elect of the United States slowly descended the stairs of the Illinois & Mississippi telegraphic office and disappeared down the street, "without a sign of anything unusual."

A contemporary later heard that Lincoln arrived home to find his wife not waiting up for him, but fast asleep. He "gently touched her shoulder" and whispered her name, to which "she made no answer." Then, as Lincoln recounted: "I spoke again, a little louder, saying 'Mary, Mary! we are elected!' " Minutes before, the final words his friends heard him utter that night were: "God help me, God help me."

From Lincoln President-Elect by Harold Holzer. Copyright © 2008 by Harold Holzer. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc., NY.