Eleven Years After Katrina, What Lessons Can We Learn Before the Next Disaster Strikes?

Author and playwright John Biguenet offers his thoughts on the narrative of destruction

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/e8/35e8524b-393c-4ea3-a3fa-9992c3e44930/1200px-katrina-14512.jpg)

Soon after the levees collapsed and Lake Pontchartrain spilled out over 80 percent of New Orleans—with thousands still stranded on their rooftops or trapped in their attics—author and playwright John Biguenet penned an essay that would lead to a series of columns on the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in the New York Times. He’d evacuated the city before Katrina hit and would return again just weeks later. In the meantime, however, he watched from afar as his hometown rotted in the catastrophic floodwaters.

“For someone whose family has lived in New Orleans since the 18th century, who grew up there speaking the patois into which locals still fall among themselves, who takes his coffee with chicory and his jambalaya with cayenne, only one word encompasses my sense of displacement, loss, and homesickness as we made our way through America this past month,” he wrote in September 2005. “Exile.”

Currently chair of the English Department at Loyola University in New Orleans, Biguenet is the author of ten books including The Torturer’s Apprentice, a collection of short stories, and Oyster, a novel set in Plaquemines Parish in 1957, as well as numerous plays, including his most recent collection, The Rising Water Trilogy, a direct response to the flood and its aftermath. Upon this 11th anniversary of the levee breaches, Biguenet reflects on the lingering effects, how the city’s creative community battled against the onslaught of misinformation, and the country’s response to his defense of New Orleans.

You started writing about the devastation in New Orleans for the New York Times in the immediate aftermath of the levee collapse. How did conditions on the ground affect your reporting process?

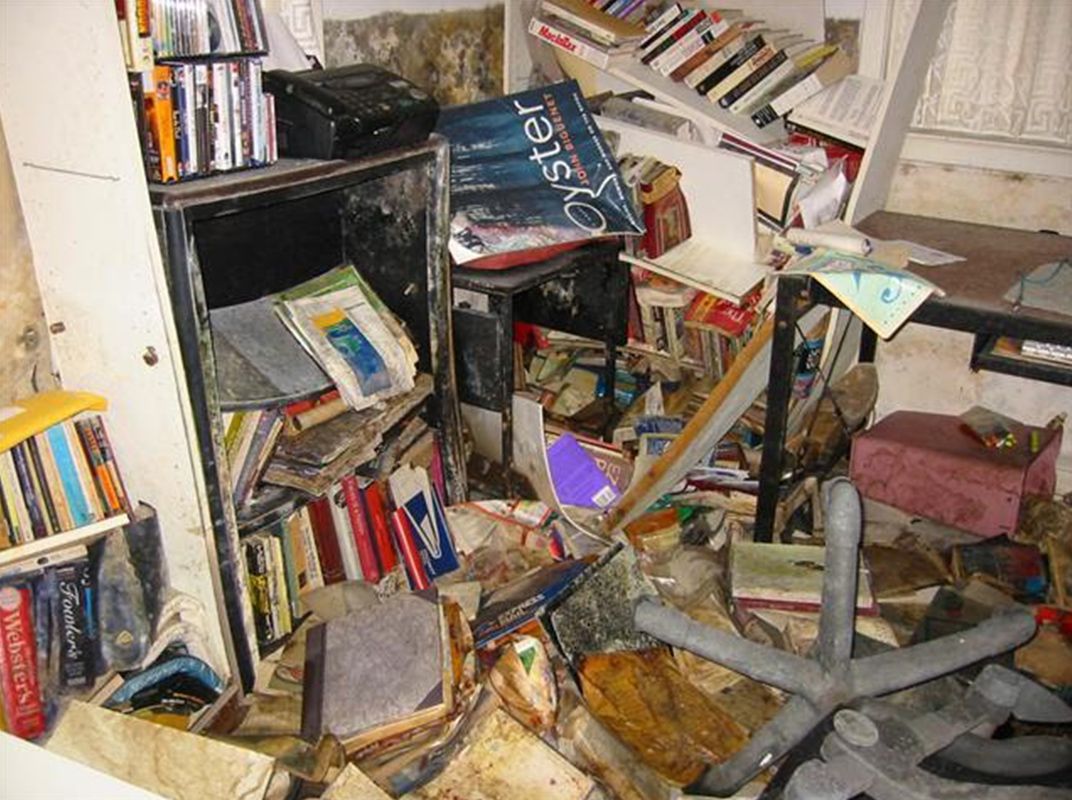

When we returned to the city on the day [five weeks later] when martial law was lifted, I kicked open our swollen front door to find our house uninhabitable and reeking of mold. Our large sofa had floated onto the staircase, our bookcases at some point had collapsed with our nearly 2,500 books dumped into the fetid flood in our living room and study, and our kitchen cabinets held pots, bowls, and cups that were still full of the saltwater that had flooded the city.

Sleeping in a daycare center, I wrote 15 columns for the Times that first month back. With my computer propped on an 18-inch plastic table while I sat on a 12-inch child’s stool, I described life among the ruins of New Orleans and tried to explain how it could have flooded when Hurricane Katrina had only sideswiped the city as the storm followed the Mississippi state line north.

But those columns were written in the evenings after my wife, my son and I had spent the day gutting our house, dragging our refrigerator to the curb as it leaked stinking puddles of food that had liquefied in our absence, attacking the rank and slimy mold that covered most surfaces, and trying to figure out how we were going to be able to live in a city nearly completely destroyed. We had been warned to leave our neighborhood before dark because of the absence of residents and the continued looting of abandoned houses— our section of the city [Lakeview] still had no power, so there were no streetlights or stoplights, just pitch darkness at night. And since the daycare center didn’t have hot water yet, we’d end the day taking cold showers before I wrote my columns and began the search for an open coffee shop with free Wi-Fi to send what I had written to New York.

In addition to the incompetence of FEMA under the Bush administration, we also faced bottom-line insurance companies. Our struggles with the nine adjustors who rotated during the year it took to settle our claim resulted in my wife finally telling one of them, “Just give us back our 30 years of premiums, and we’ll call it even.” The adjustor laughed.

But despite FEMA and the insurance company and the cold showers each night, I wrote 15 columns and shot two videos for the Times by the end of October 2005. A year later just as we moved back into the second story of our house while we continued to work on the first floor, I wrote a second series of columns about the aftermath of the flood.

Given all the chaos in and around New Orleans following the floods, how concerned were you about the veracity of the information you were presenting?

Writing for the Times, I was of course required to confirm what I had written. So it wasn’t mere opinion that the levees had been undermined rather than overtopped. All one had to do was look at the water line on the inside walls of a levee to see that the water hadn’t come within three feet of the top of it. And if you went to the canals that had actually breached, you could see that the steel had been bent out from the bottom. So it wasn’t an opinion; there was simply no other explanation. Anybody who knew the city and took a walk on the top of the levees would have known immediately what had happened. And within months, various forensic engineering studies confirmed the facts as well as the cause of the levee failures.

The canals were supposed to hold 20 feet of water. I was told the rule of thumb is that, in building a levee, you need three times that amount of steel plus a margin. So for a 20-foot canal, you need 65 feet of steel. In some places the [U.S. Army Corps of Engineers] didn’t have enough money for that, so according to news reports, they used from four-and-a-half feet of steel in some spots to 16 feet in others, and the rest was just mud. And they didn’t have enough money to test the soil. The soil was alluvial swamp, which is just like coffee grinds. So when the canals became engorged with water pushed into Lake Pontchartrain by the storm, the pressure—you can imagine 20 feet down how much water pressure that is—just spit through those coffee grinds and, when it did, ripped open what steel was there.

By June 2006, when the report by the Corps was finally released, the United States was facing so many problems, especially the collapse of our efforts in Iraq, that the country had moved on from the flooding of New Orleans. The Corps of Engineers had spent nine months insisting over and over again that the levees had been overtopped. When they finally told the truth, nobody was paying attention anymore. That’s why Americans and even the news media still blame Hurricane Katrina for the flooding. But no one down here talks about Katrina—they talk about “The Federal Flood” or the levee collapse.

In the end, the Corps wrapped itself in sovereign immunity and admitted responsibility but not liability.

What role do you believe race played in the country’s reaction to the levee collapse?

My play Shotgun, set four months after the flood, is really about race in New Orleans in the aftermath of our catastrophe. At first, we were all in so much trouble that old animosities got put aside, including racial tensions. If the back tire of a car had fallen into a collapsed manhole and the driver had kids in the backseat, nobody was going to ask what color that family was—they were just going to help lift the car out of the hole. But as it became clear that we could expect little help from the government and so would have to rebuild on our own, old prejudices reemerged. [Mayor Ray Nagin] faced re-election that spring, and on Martin Luther King Day, he made his “Chocolate City” speech, in which he alleged that Uptown whites were plotting to keep black New Orleanians from returning to their homes.

At that point, the poorest New Orleanians, many of whom were black, were living in Houston and Atlanta and Baton Rouge. With tens of thousands of houses uninhabitable, most jobs gone, and the public schools closed for the entire year, many homesick citizens were desperate for a leader to represent their interests. Driving into Houston just before the [New Orleans] mayoral election, I saw a billboard with a photograph of Nagin and a simple message: “Help him bring us home.” He won reelection by a few thousand votes.

Playing to long-simmering racial animosity, the mayor’s speech transformed everything in the city—and that’s what my play is about.

With firsthand experience of how a politician can exploit racial fears, I find it hard not to see much of what is going on in the country right now as racist at its foundation. To suggest that the Federal government exists simply to steal your money and give it to people who are too lazy to work is merely a current variation on the old conservative argument that your taxes are going to welfare queens. When [Republican House Speaker Dennis Hastert] argued in 2005 for the bulldozing of New Orleans, it was difficult to believe Congress would have taken the same position if a majority-white city had suffered a similar manmade disaster.

Did you feel any specific responsibilities as an artist living in New Orleans at the time?

Every writer and photographer and musician and artist in the city put aside personal projects and focused on getting the message out—and trying to contradict the misinformation. Tom Piazza, a friend of mine, wrote Why New Orleans Matters because there really was a sense that Washington was just going to write off the city. All of us did whatever we could to keep the story alive.

Also, to be fair, the United States had never lost an entire city before. The area flooded was seven times the size of the entire island of Manhattan. The scope of it was so vast that one could drive for an hour and see nothing but devastation. It’s very, very hard—if there’s no existing narrative model—for a writer to organize the information he or she is gathering and then for a reader to make sense of those bits and pieces of information that are coming from various media.

It’s much easier for everyone to fall into the hurricane narrative. It’s a three-part story. On the first day, the weather reporter is leaning into the wind saying, “Yeah, it’s really blowing here.” The next day, it’s people standing on the slab of their house weeping as they say, “At least we have our lives to be grateful for.” And the third day, with shovels in hand, they’re digging out and rebuilding. But here on the third day, New Orleanians were still on their rooftops waiting for the United States to show up. It was the end of the week before significant American aid began to arrive, nearly four days after the levees had breached, with people on rooftops or dying of dehydration in their attics that whole time.

So how do you tell a story about something that has never happened before? When I started writing my plays about the flood and its aftermath, I looked at post-war German writers, Russian writers after Chernobyl, Japanese writers after the Kobe earthquake—for example, After the Quake by Haruki Murakami—and studied the ways they addressed the destruction of whole cities. Invariably, they used something deep in their own mythologies.

We’re going to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the founding of New Orleans in 2018, so we’re not old enough to have a substantial mythology. But I thought if I could find something characteristic of the city to tell the story of what had happened, something that might serve in the same way as a mythology for a bigger, older culture, I could address what we had lost. And it occurred to me that architecture could be used as a structuring principle for the plays. Especially because the iconic images of the flood were of people trapped on rooftops, houses offered a central motif that was expressive of both our climate and our culture. The first play in my Rising Water trilogy is set in an attic and then, in the second act, on the roof. The second play, Shotgun, takes place in a shotgun duplex, the most characteristic form of local architecture. And the third play, Mold, is set in a house enshrouded in mold and on the verge of collapse. In a very real sense, architecture gave me a narrative structure.

How have readers responded to your analysis of New Orleans and the aftermath of the levee collapse?

Eleven years ago, the responses I received to my columns in the Times expressed profound disappointment in the federal government’s response to the disaster, especially from readers abroad. As a person wrote about one of my columns, “Don’t the Americans understand that New Orleans doesn’t belong to the United States? It belongs to the world.” International opinion about this country shifted dramatically because of that and, of course, because of what was happening then in Iraq.

Thanks to my columns, I wound up hosting a number of international journalists when they visited New Orleans after the flood. Their reaction was summed up by one foreign correspondent who turned to me after we had driven around the city and, shaking his head, said in disbelief, “This is simply not possible. Not in the United States.”

However, things in our country have changed a great deal in the last decade. In response to my essay in the New York Times last year on the tenth anniversary of the levee breaches, many Americans were much less generous: “You people chose to live there. Don’t come crawling to us for help the next time a hurricane hits.” These sentiments were expressed by those living on the fault line in San Francisco, in the Midwest’s tornado alley, in Western areas frequently swept by summer firestorms. Do they think the rest of us are not going to help them rebuild when the next disaster hits there?

But it takes a community to do that, and there’s a very strong sense, in the responses to what I’ve written, particularly in this last year, that “it’s your own damn fault and don’t expect any help from us.” I think it’s just another expression of the enormous anger that is circulating through our country right now. Nobody wants to be held responsible for his or her neighbor’s problems, and I think that attitude is very destructive to a sense of community and, of course, to our nation.

Do you consider yourself a place-based writer?

I just think of myself as a writer. But I know New Orleans and the surrounding environment. At the end of the introduction to The Rising Water Trilogy, I argue that New Orleans is simply where the future arrived first. If you don’t pay attention to environmental degradation, to climate change, to rising water levels, to coastal erosion, to endemic poverty, to substandard education, to political corruption, to the substitution of ideology for intelligence, you get what happened to New Orleans in 2005. I think Hurricane Sandy confirmed my argument that this was just the first place to experience what the future holds in store for the country and the world. But that also means if you want to understand what’s going to happen in the coming century in terms of the relationship of the environment to human civilization, this is a place where you can witness it.

I’ll give you a very straightforward example. When I was a child, we were taught there were 100 miles between New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. My children were taught there were 50. Now it’s 12 miles to the east. I was giving a talk on the tenth anniversary of the levee collapse last year, and there was an environmentalist who also spoke that night. He showed projections of what New Orleans will look like in the year 2100, and it’s not going to be merely on the coastline, as Biloxi is today. It’s going to be an island. It will be off the coast of the United States if current trends persist. So we are in a laboratory living here in New Orleans for the intersection of the environment and human life. We can see the future happening.

How does the history of a place like New Orleans affect how you write about it?

There are 14 stories in my collection The Torturer’s Apprentice, and three of them are ghost stories. The convention of the ghost story is very useful in showing how the past persists into and sometimes affects the present. Those who think about New Orleans usually imagine the French Quarter. They imagine buildings that may be 200 years old and a way of life that precedes even that—including the dark history of this place.

For example, right across the street from the Napoleon House—the old governor’s mansion that was set aside for Napoleon as part of a failed plot local Creoles hatched to bring the exiled emperor here to start a new empire—is Maspero’s slave exchange. Sitting in the Napoleon House, you can still see across the street barred windows between the first and second floors where slaves had to squat before they were brought downstairs to be auctioned off. That history is all around us, and if you know the city, the past is still here—but so is the future.