Enslaved Tour Guide Stephen Bishop Made Mammoth Cave the Must-See Destination It Is Today

In the 1830s and ‘40s, the pioneering spelunker mapped out many of the underground system’s most popular spots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/77/16778954-937b-408a-8d8c-a927c5d5fb24/38160987522_18f2cfde5f_k.jpg)

Underneath the rolling sinkhole plains of central Kentucky lies Mammoth Cave, a limestone labyrinth with 412 miles of underground passageways stacked on top of each other in five different levels. It's the longest cave system in the world, and no one knows exactly how far deep it goes—an estimated 600 miles of passages are still unexplored. A Unesco World Heritage Centre, Mammoth Cave contains every type of cave formation—from icicle-like stalactites to eerie white gypsum flowers—and 130 species of wildlife. Every year, National Park Service guides lead 500,000 visitors through tight passageways, steep shafts and vast chambers that, millions of years ago, were formed by gushing water. Yet without the slave labor of Stephen Bishop, it’s unclear how much of the cave we would know about today.

In 1838, Bishop, then 17, was brought to the cave by his owner, Franklin Gorin, a lawyer who wanted to turn the site into a tourist attraction. Using ropes and a flickering lantern, Bishop traversed the unknown caverns, discovering tunnels, crossing black pits, and sailing on Mammoth’s underground rivers. It was dangerous work. While today much of the cave is lit by electrical lights and cleared of rubble, Bishop faced a complex honeycomb filled with sinkholes, cracks, fissures, boulders, domes and underwater springs. A blown-out lantern meant isolation in profound darkness and silence. With no sensory impute, the threat of becoming permanently lost was very real. Yet it’s hard to overstate Bishop’s influence; some of the branches he explored weren’t found again until modern equipment was invented and the map he made by memory of the cave was used for decades.

Archeological evidence shows that Native Americans explored the first three levels of the cave between 2,000 and 4,000 years ago. After that, little activity has been chronicled until white settlers rediscovered it in the 1790s. During the War of 1812, enslaved laborers mined Mammoth for nitrates to be processed into saltpeter for ammunition. Word of mouth spread, and people began to seek out this strange geological wonder. Tours began in 1816. For a short period, there was even a church inside the cave. Then, in spring 1838, Gorin purchased it for $5,000. At the time, eight miles of passages were known.

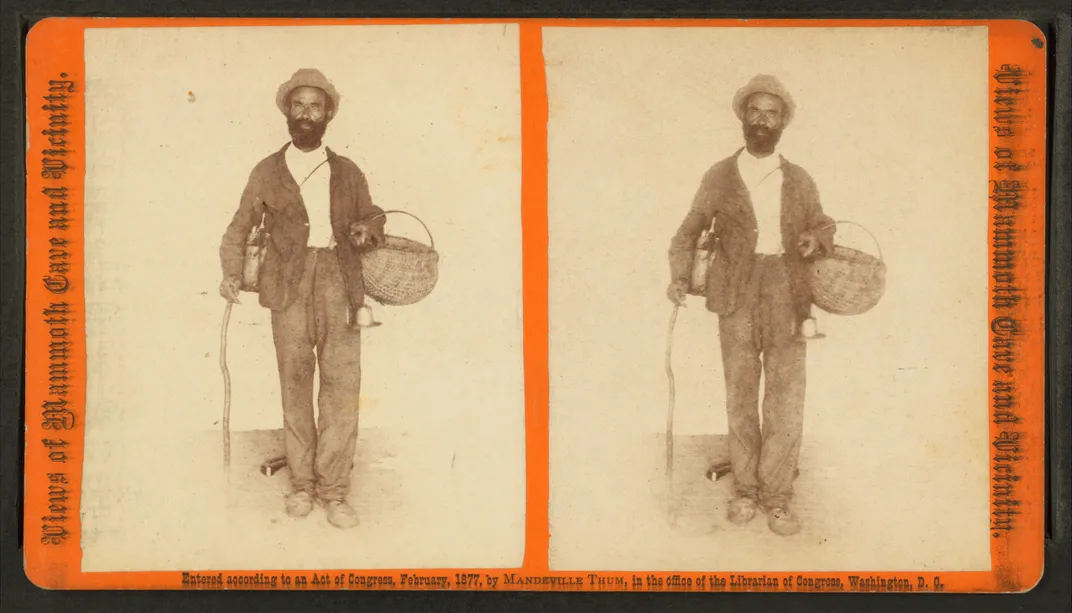

Noted spelunker Roger W. Brucker wrote in a 2010 issue of The Journal of Spelean History that Stephen Bishop came to Mammoth Cave by way of a divorce settlement between a white Kentucky farmer named Lowry Bishop and his wife. Gorin was Bishop’s lawyer during the proceedings, in which his “wife sued on the grounds of adultery, and obtained a judgment of one-half of Lowry’s property.” After the divorce, Lowry wrote in an 1837 document that if he died, his estate could be used to settle his attorney’s fees. Stephen, who was likely Lowry's biological son, is thought to have been part of that settlement, because Gorin acquired him that year. He was then trained as a cave guide by the former superintendent of the mining operation, and he, in turn, trained Mattison (Mat) Bransford and Nick Bransford—no relation to each other—who Gorin leased from their owner for $100 a year. Their signatures, which they made with candle smoke, appear throughout the cave.

“We can find [their names] in places that kind of frighten me to go today, and we have modern lighting,” says Jerry Bransford, a Mammoth Cave guide and Mat Bransford’s great-great grandson. “I’m thinking that if you were in slavery and you were charged to explore the cave, you were free in the cave to make a life however you wanted. I think they knew that if they did this well enough, life would be much better than in the hay field or the barn lot.”

Bishop quickly came to be an expert on Mammoth Cave. When one visitor supposedly offered him a “fistful of money” to take him somewhere new, Bishop decided to cross the 105-foot Bottomless Pit, a cavern so deep torches disappeared when thrown into it. The story goes that Bishop placed a ladder across the pit and, carrying the lantern in his teeth, crawled to the other side. Later, he discovered Fat Man’s Misery, an ancient riverbed with narrow, winding passages. It was filled with silt, and Bishop had to dig his way through. The farther he went, the lower the ceiling became until he found himself in Tall Man's Misery. Finally, he came out the other side, stood up, stretched, and named the area Great Relief Hall—which it's still called today.

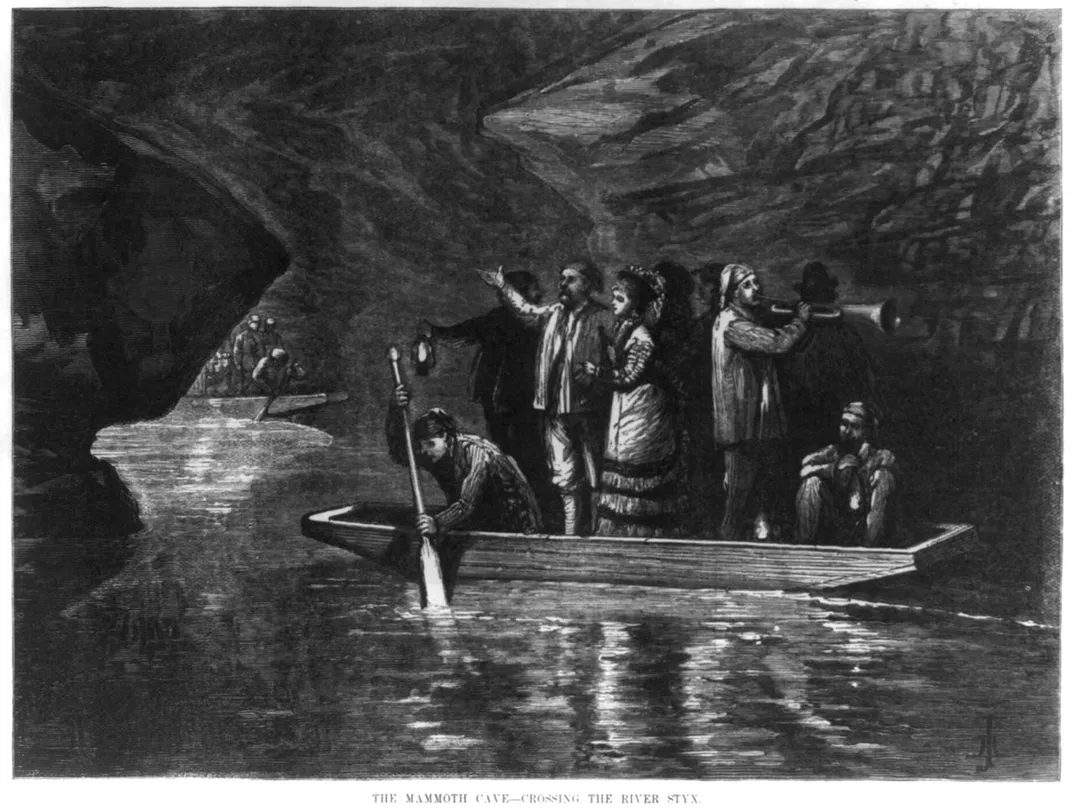

He then went on to find Lake Lethe, River Styx and Echo Rivers on the cave’s bottom level, 360 feet below surface. There, he encountered eyeless fish and cave crayfish, both blind and bone white. He dragged boat-making materials into the cave and sailed on the rivers, which was later included on the tours.

Gorin owned Mammoth Cave for just a year before selling it to John Croghan for $10,000, a price that included Bishop. During that year, two more miles of the cave had been discovered. Croghan, the nephew of William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, constructed roads near the cave, improved existing buildings, and renovated the nearby hotel. During this time, Bishop and the two Bransfords continued leading tours, which sometimes included famous visitors such as opera singer Jenny Lind, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and many respected scientists.

These tours were all-day excursions, sometimes lasting 18 hours. With only lantern light to pierce the darkness, the tourists made their way across debris, down ladders, and over rocks and boulders. Like Bishop, they smoked their names on the ceiling.

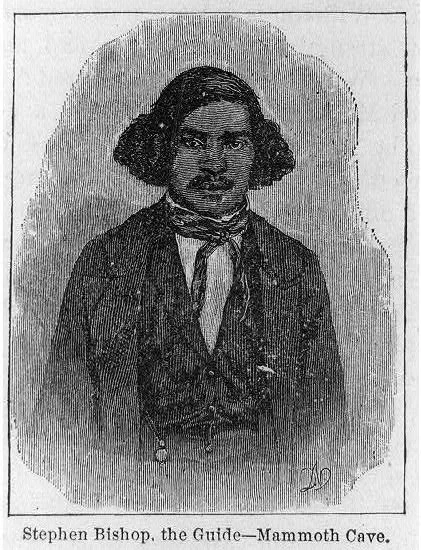

Most contemporaries who wrote about Mammoth Cave described Bishop as well. JW Spaulding’s 1853 article in The Northern Inquirer calls Bishop as “the most intelligent Negro … that I met with in all my travels” who “can converse on geology and mineralogy with much fluency, and would put to the blush many who have seen much of Academic halls.” Bishop showed Spaulding gypsum-crystal “stars” that looked like the night sky and sang a song on the Echo River, his “clear, sonorous voice” filling the cave. “There are two or three guides, who are procured at the hotel,” Spaulding writes. “If possible, get Stephen.”

As word spread, so did Bishop's fame. In Health Trip to the Tropics, author Nathaniel Parker Willis seems star struck upon meeting him. “The first glance told me that Stephen was better worth looking at than most celebrities,” he wrote, then breathlessly described Bishop’s “masses of black hair,” “long mustache,” and his clothes: “chocolate-colored slouched hat, a green jacket and striped trousers.”

Passages like these are steeped in outdated concepts of race and 19th-century romanticism. Still, a common picture emerges of a man who was well-spoken, knowledgeable, slim and athletic. He’s thought to have learned much from the long hours with the wealthy clientele. At the end of his life, Bishop could speak some Greek and Latin, read and write, and knew so much about geology that visiting scientists picked his brain for information.

“In the cave, you can see his education progress,” says park ranger Kennetha Sanders. “There’s one signature from when he first came here, in 1838 or so, that looks like a preschooler writing his name, with block writing. Later on, it was cursive.”

However, Bishop’s reality was that of an enslaved man. In the 1856 book Letters from the United States, Cuba and Canada, British botanist and author Amelia Murray writes that Bishop reminds her of a “good-looking Spaniard” before gushing about the great service in the cave. The enslaved “watch your every motion with such eager curiosity, and will hardly let you stir without their help.” The guides were responsible for the guest’s safety, yet couldn’t dine with them. More than once, Bishop carried injured or weakened men who outweighed him on his back for miles to safety.

“Admittedly, their work was unusual, but the slave economy, wherever it existed, relied on the skills and talents of the enslaved,” says Richard Blackett, history professor at Vanderbilt University. “The system could not have functioned without the skills of the slaves.”

While Croghan encouraged tourism, he had other reasons for purchasing Mammoth Cave: a cure for tuberculosis. Years before scientists understood germ theory, Croghan thought that the pure air and constant temperature of the cave might have positive effects on the disease. Bishop, the Bransfords , and possibly other enslaved workers built huts at different levels in the cave, two of which can still be seen today. Thirteen patients moved in, intending to stay for a year. Tours passed by the tuberculosis experiment and visitors often interacted with the patients.

“We can only imagine how life would be, living a mile into the cave, having your own little hut back there,” says Jerry Bransford. “When the slaves would bring tours through, these people in the huts would come out and and say, 'oh, we're so glad to see you' ... and then they would cough and contaminate other people.”

After a few months, three patients died, and the experiment was shut down.

In 1842, Croghan summoned Bishop to Locust Grove, his Louisville mansion, to draw a map of Mammoth Cave. It was published in Rambles in the Mammoth Cave, During the Year 1844 by Alexander Clark Bullitt. “[It was] very accurate in terms of the topography and relationship of the various aspects of the cave’s many branches, less accurate in terms of exact distances,” says Carol Ely, executive director at Locust Grove. She adds that the map was “considered remarkably accurate in its time.” was considered so accurate, the Bishop map was used into the 1880s.

While at Locust Grove, Bishop met Charlotte, another enslaved worker. They married, and Charlotte went to live with him in the slave quarters near Mammoth Cave, where she worked at the hotel. Bishop took her to a fairy-like section of the cave filled with gypsum flowers and named it Charlotte’s Grotto. On a wall, he drew a heart and wrote: “Stephen Bishop, M Cave Guide, Mrs. Charlotte Bishop 1843.” Beside that, he wrote, “Mrs. Charlotte Bishop, Flower of Mammoth Cave.” While the heart still can be seen, it's not part of a tour today.

It's unclear how Bishop viewed his job. Gorin said that he called Mammoth Cave “grand, gloomy, and peculiar,” words that seem ambivalent. When Croghan died in 1849 from, predictably, tuberculosis, his will stated that the 28 people he enslaved would be freed seven years after his death, including the Bishops. As the time neared, several people wrote that Bishop was planning to move to Liberia. “He is at present a slave, but is to have his freedom next year, and then goes to Liberia with his wife and family,” wrote Murray. “He would not wish to be free in this country.”

In 1856, Charlotte and Stephen were emancipated. In July 1857, they sold 112 acres they owned near the cave. It's unknown how they acquired the land, although, as a guide, Bishop received tips from visitors. A few months later, Bishop died at age 37 from mysterious causes. He led a tour shortly before his death, and the previous August, he’d discovered a new section of the cave, extending explored passageways to 11 miles.

He was buried in an unmarked grave in front of Mammoth Cave. In 1878, millionaire James Mellon told Charlotte that he would send her a headstone. Three years later, it arrived. It was an unclaimed Civil War headstone, and the original name was scratched out. The date of death was wrong by two years. Still, it reads: “Stephen Bishop: First guide and explorer of Mammoth Cave.”

“When you come to Mammoth Cave, it's really hard to leave and not hear about Stephen Bishop,” says Sanders, adding that the tour guides even have a joke about it. “How do you know you're a Mammoth Cave guide? You know more about Stephen Bishop than you do about your best friend.”